Soldaderas

Soldaderas, often called Adelitas, were women in the military who participated in the conflict of the Mexican Revolution, ranging from commanding officers to combatants to camp followers.[1] "In many respects, the Mexican revolution was not only a men's but a women's revolution."[2] Although some revolutionary women achieved officer status, coronelas, "there are no reports of a woman achieving the rank of general."[3] Since revolutionary armies did not have formal ranks, some women officers were called generala or coronela, even though they commanded relatively few men.[4] A number of people assigned female at birth, took male identities, dressing as men, and being called by the male version of their given name, among them Ángel Jiménez and Amelio Robles Ávila.[4]

The largest numbers of soldaderas were in Northern Mexico, where both the Federal Army (until its demise in 1914) and the revolutionary armies needed them to provision soldiers by obtaining and cooking food, nursing the wounded, and promoting social cohesion.[5][6]

In area of Morelos where Emiliano Zapata led revolutionary campesinos, the forces were primarily defensive and based in peasant villages, less like the organized armies of the movement of Northern Mexico than seasonal guerrilla warfare. "Contingents of soldaderas were not necessary because at any moment Zapatista soldiers could take refuge in a nearby village."[5]

The term soldadera is derived from the Spanish word soldada, which denotes a payment made to the person who provided for a soldier's well-being.[7][8] In fact, most soldaderas "who were either blood relations or companions of a soldier usually earned no economic recompense for their work, just like those women who did domestic work in their own home."[5]

Soldaderas had been a part of Mexican military long before the Mexican Revolution; however, numbers increased dramatically with the outbreak of the revolution. The revolution saw the emergence of a few female combatants and fewer commanding officers (coronelas). Soldaderas and coronelas are now often lumped together. Soldaderas as camp followers performed vital tasks such as taking care of the male soldiers: cooking, cleaning, setting up camp, cleaning their weapons, and so forth.

For soldaderas, the Mexican Revolution was their greatest time in history.[9] Soldaderas came from various social backgrounds, with those "to emerge from obscurity belonged to the middle class and played a prominent role in the political movement that led to the revolution."[10] Most were likely lower class, rural, mestizo and Native women about whom little is known. Despite the emphasis on female combatants, without the female camp followers, the armies fighting in the Revolution would have been much worse off. When Pancho Villa banned soldaderas from his elite corps of Dorados within his División del Norte, the incidence of rape increased.[11]

They joined the revolution for many different reasons; however, joining was not always voluntary.[12]

Differences between army factions

The Federal Army had large numbers of camp followers, often whole families of the troops. Women were important logistical support to male combatants, since the army did not have an organized way to provision troops. Women sourced food and cooked it for individual soldiers.[10] For the Federal Army, its forced recruitment of soldiers (leva) meant that desertion rates were extremely high, since army service was a form of "semi-slavery." By allowing families to remain together, desertion rates were reduced.[10] Much is known about the soldaderas of General Salvador Mercado's army, since he crossed the U.S. border after being beaten by Pancho Villa's army. Some 1,256 women and 554 children were interned in Fort Bliss along with 3,357 army officers and troops.[13] When Villa heard of the plight of the destitute Mexican women at Fort Bliss who had appealed to Victoriano Huerta's government, Villa sent them 1,000 pesos in gold.[14]

In Northern Mexico, the early revolutionary forces (followers of Francisco I. Madero) that helped overthrow Porfirio Díaz in 1911 lacked camp followers, because there was not much need for them. Revolutionary combatants were mostly cavalry who operated locally rather than far from home as the Federal Army did. Horses were expensive and in short supply, so in general, women remained at home.[15] There were some female Maderista combatants, but there are no reports of there being significant numbers of them.[10]

In Southern Mexico, the Zapatista army, for the decade of revolutionary struggle, the combatants were usually based in their home villages and largely operated locally, so that camp followers were not necessary. The revolutionary army of the south recruited volunteers from villages, with many campesino villagers remaining non-combatants (pacificos). Sourcing food in the agriculturally rich region of Morelos did not necessitate camp followers, since villages would help out and feed the troops. When the Zapatistas operated farther from home and because the Zapatistas forces lacked camp followers, Zapatistas' rape of village women was a well-known phenomenon.[16]

After the overthrow of President Madero in February 1913 by General Victoriano Huerta, northern armies became armies of movement fighting far from home. The Constitutionalist Army divisions now utilized trains rather than cavalry to move men and war materiel, including their horses, as well as soldaderas. The change in technology enabled the movement of combatants, women and children, with horses and male soldiers inside box cars, with women and children on top of them. This created a situation similar to that of the Federal Army, where allowing soldiers to have their wives, sweethearts, and possibly their children with them, soldiers' morale was better and the armies could retain their combatants. In the region where Villa's División del Norte operated, the railway network was more dense, allowing for greater numbers of women to be part of the enterprise. The women and children utilized all possible space available to them, including on the cow-catchers at the front of locomotives.[17] In the region where Constitutionalist general Álvaro Obregón operated in Sonora, the network was less dense, there was more use of just cavalry, and fewer women and children.[10]

When the revolutionary factions split after the ouster of Huerta in 1914 and Obregón defeated his former comrade-in-arms Villa at the Battle of Celaya, Villa's forces were much reduced and were again on horseback. This smaller, more mobile Villista force no longer included female camp followers, and rape increased.[18] A reported Villa atrocity with corrobaration was his killing of a soldadera supporting Villa's former First Chief, Venustiano Carranza, political head of the Constitutionalist faction. In December 1916, a Carrancista woman begged Villa for her husband's life; when informed he was already dead, the new widow called Villa a murderer and worse. Villa shot her dead. Villistas worried that other Carrancista soldaderas would denounce the death when their army returned, they urged Villa to kill the 90 Carrancista soldaderas. Villa's secretary was repelled at the scene slaughter, with the women's bodies piled upon one another, and a two-year-old laughing on his mother's body. Elena Poniatowska gives a slightly different account. The story is that there was a shot fired from a group of women, towards Villa. None of the women, whether they actually knew or not, gave up a culprit. Villa then ordered his men to kill every single woman in the group. Everyone, including children, was killed. Villa's troops were then told to loot the bodies for valuables. During their search they found a baby still alive. Villa told them that their orders were to kill absolutely everyone, including the baby.[19] For Villa biographer Friedrich Katz, "In moral terms, this execution marked a decisive decline of Villismo and contributed to its popular support in Chihuahua."[20] Further Villista atrocities were reported in the Carrancista press.[21]

The treatment of women varied between different leaders, but in general they were not treated well at all. Even horses were said to be treated better than they were.[22] The horses were valued much more, and so when traveling by train, the horses rode inside train cars while women traveled on the roof. Traveling by train was already risky since revolutionaries was known for blowing up trains and railroads. Being on the roof in plain sight was even more dangerous.[23] There are also stories of women being used as shields to protect Alvaro Obregón's soldiers.[24] Life for a soldadera, camp follower or soldier, was extremely hard.[25]

Reasons for participating

Force

One reason for joining the revolution was through brutal force. Male soldiers often kidnapped women and forced them to join armies.[26]

Other times soldiers would turn up at villages and demand that all the women there join. If the women refused they would be threatened until they gave in or else would be shot and killed. These kidnappings were no secret in Mexico and were frequently reported in the country’s newspapers. In April 1913, the Mexican Herald newspaper reported that 40 women were captured from the town of Jojutla, by Zapatista armies, as well as all the women from a neighboring town two kilometers away.[27] Although newspaper reports did alert readers to such issues, literacy rates for women, especially in the countryside, were extremely low, only averaging around 9.5% of the women.[28] This meant that majority of the women would only be able to get information about kidnappings and other dangers by word of mouth. This process would mean that it was probably too late for them to help themselves by the time revolutionary armies appeared in their town. Another form of forcefully making women join the revolution was by a woman’s husband, with his wanting his wife to take care of him while he was at war. John Reed once asked a soldier why his wife had to also go and fight in Villa’s army, and he responded by saying, "shall I starve then? Who shall make my tortillas but my wife?"[29]

Protection

Another reason to join the revolution, and probably the most common, was for protection from the men in their family, most often either their husband, father, brother, who had joined one of the revolutionary armies.[30] There was a great need for protection for females as there would be very few males left in their villages, one of the reasons why revolutionary armies had such an easy time going to these villages and forcing the women to join them. It was a very common event for a woman to follow her husband and join whatever force he was fighting for, and she was most likely to be more than willing to do so.[31] Especially once the kidnappings began to be more frequent, women who had initially stayed home decided to join the male family members that were fighting. In 1911 in the town of Torreon, a young female named Chico ended up being the last female left in her household because Orozco’s troops had rampaged the village and killed her mother and sisters.[32] Just like Chico, numerous females joined the forces for the protection of male family members.

Other reasons

Some older women would join the armies as an act of revenge towards Victoriano Huerta's regime. These women would have had husbands, brothers or sons killed by the Federal Army and so with less to live for they would join the fight for the Revolution.[30]

Some women supported the ideals for which the armies were fighting, whether the revolutionary or federal armies. More lower class females joined the fight and were fighting on the side of the revolutionary forces. One of the reasons for the Revolution was to have some sort of land reform in Mexico, and since lower-class people’s lives depended on farming, it made sense to join the side they did.[33]

Roles

Camp followers

Camp followers had numerous roles to fulfill, all of which related to looking after the male soldiers. Some of the basic roles would be to cook the meals, clean up after meals, clean the weapons, to set up camp for the army, and provide sexual services. Often, the women would get to the camp site ahead of the men in order to have camp all set up and to begin preparing the food so it was almost ready by the time the men showed up.[33] Foraging, nursing and smuggling were also some of the other tasks they had. Towns that had just previously been fought in were the perfect location for foraging. Once the soldiers had left the women would loot stores for food and search through the dead bodies looking for anything that could be of value or use. Taking care of and nursing the wounded and sick was also another important task women had to fulfill. It was an extremely important role since medical care was not available to most of the soldiers and these women were their only chance of survival if they were wounded. If the army was in an area close enough to a hospital, then the women would also be responsible to get the soldiers that were badly wounded there, pulling them along in ox-carts. Not only did camp followers perform these duties, but also had a much more war-like task. They would have to smuggle hundreds and hundreds of rounds of ammunition to the fighting forces, especially from the United States into Mexico. They would hide the ammunition under their skirts and breasts and were given this duty because they were perceived as harmless women and therefore hardly ever caught.[34]

Defense of symbols of the revolution

After the forced resignation and murder of Francisco I. Madero during the counter-revolutionary coup of February 1913, Madero's grave in Mexico City was subject to vandalism by adherents of the new regime. María Arias Bernal defended it against all odds, and was given public recognition for her bravery by Constitutionalist Army General Álvaro Obregón.

Medical support

An important role that women played during the Mexican Revolution's violence was as nurses. Most were likely anonymous, and nursed without being part of a formal organization or equipment. However, a significant figure was Elena Arizmendi Mejia, who created the Neutral White Cross when the Red Cross refused to treat revolutionary soldiers. Arizmendi was from an elite family and knew Francisco Madero before he was president. The Neutral White Cross leadership attempted to oust her from leadership when she was photographed in the pose of a soldadera or coronela, with crossed bandoliers, supposedly as a joke for her paramour, José Vasconcelos, later to become Minister of Public Education in the Obregón government.[35]

Female combatants

A number of women served as combatants, but how many is not known. Some women became combatants by first joining the army passing as male, speaking in deep voices, wearing men’s clothing,[36] and wrapping their breasts tightly to hide them.

For those that were known to be female and not in disguise, some served as spies, surveilling enemy armies, dressing as women and joining the camp followers of an enemy army in order gain inside information. They would also be given important information that they would have to relay between generals of the same army. Some would say they were given this task because they were trusted, but more likely the reason would be because males still did not see these women as equals and being messengers seemed like a more feminine role of a soldier.[37]

Notable individuals

Petra / Pedro Herrera

One of the most famous female combatants was Petra Herrera.[38] At the beginning she dressed as a man and took the given name of Pedro, joining the ranks of Villa’s army. She kept her identity a secret until she had been acknowledged as a great soldier. Once she established her reputation, "she let her hair grow, plaiting it into braids, and resuming her female identity".[39] According to one of Villa’s troops, Herrera was the person who should have been credited for the siege of the town of Torreón. However, Villa was not willing to have a female take credit as an important role in a battle and therefore she was never given what she deserved. As a result of her lack of acknowledgment, she left Villa’s troops and formed her own troop of all female soldiers. She became an ally of Carranza and his army and became a legend for all females around the country.[40]

Angela / Ángel Jiménez

Angela Jiménez insisted on being known as Ángel Jiménez (the male version of the name).[4] From Oaxaca, she became "an explosives expert and known for her courage in battle.[4] According to one scholar, she "refused sexual or sentimental links with the opposite sex, pledging to her comrades that she would shoot anyone who tried to seduce her."[4]

She originally joined the revolutionary forces, joining her father in fighting the federal army because there had been a raid on her village by federal troops. A federal officer was unsuccessful though and her sister managed to kill him but then right after she took her own life. Jiménez then decided to join her father fighting against the Federal Army and disguised herself as a male. She fought for multiple rebel groups but ended up fighting with Carranza and then revealed her true identity.[citation needed] Even known as a woman she rose to the position of lieutenant and earned the respect from the rest of the troops. She continued fighting against the Federal Army for years under her true identity as a female, and was a true believer that having a revolution would be the start of having justice.[41]

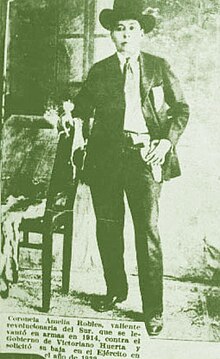

Amelio Robles Ávila

Amelio Robles Ávila, "El güero", was a distinguished soldier in the Revolutionary Army of the South. Robles had learned to ride horses and shoot from an early age, and after the revolution started, Robles dressed as a man and ultimately became a colonel in the Legionary Cavalry.[4] From 1913 to 1918, Robles fought as "el coronel Robles" with the Zapatistas. Following the military phase of the Revolution, Robles supported revolutionary general Álvaro Obregón, president of Mexico 1920–1924, as well as during the 1924 rebellion of Adolfo de la Huerta. Robles lived as a man for the remainder of his long life, which was marked towards the end by various decorations acknowledging his distinguished military service: decoration as a veteran (veterano) of the Mexican Revolution and the Legion of Honor of the Mexican Army, and in the 1970s, the award of Mérito revolucionario. Robles died December 9, 1984, aged 95.

Foreign observers

In November 1911, a Swedish mercenary, Ivar Thord-Gray, who was part of Villa's forces observed preparations for battle. "The women camp followers had orders to remain behind, but hundreds of them hanging onto the stirrups followed their men on the road for awhile. Some other women carrying carbines, bandoleers [sic] and who were mounted, managed to slip into the ranks and came with us. These took their places in the firing lines and withstood hardship and machine gun fire as well as the men. They were a brave worthy lot. It was a richly picturesque sight, but the complete silence, the stoic yet anxious faces of the women was depressing, as it gave the impression that all were going to a tremendous funeral, or their doom."[42]

A U.S. secret agent, Edwin Emerson, gave reports on Villa's army, with an observation on the women. "The conduct of the women who came along on the railway trains and many of whom accompanied their men into the firing line around Torreón was also notably heroic."[43]

Leftist journalist John Reed, a Harvard graduate, is the most well-known foreign observer reporting on soldaderas. His reports from his four months with Pancho Villa's army in 1913 during the struggle against Huerta were published as individual newspaper articles and then collected as Insurgent Mexico in 1914. In one report, he recorded the reaction of one Villa's soldier to the kidnapping of his soldadera wife by Pascual Orozco's colorados. "They took my woman who is mine, and my commission and all my papers, and all my money. But I am wretched with grief when I think of my silver spurs inlaid with gold, which I bought only last year in Mapimi!"[26] In another report, Reed recorded that women who were already soldaderas and whose man had fallen in battle often took up with another soldier. He devotes a chapter in Insurgent Mexico to a woman he calls "Elizabetta," whose man was killed and a captain of Villa's forces had claimed her as his. Reed says that the soldier "found her wandering aimlessly in the hacienda [after a battle], apparently out of her mind; and that, needing a woman, he had ordered her to follow him, which she did, unquestioningly, after the custom of her sex and country."[44]

Photographing soldaderas

The development of photography allowed for a greater range of social types recorded for history. A number were photographed in formal poses. One woman was photographed by the H. J. Gutiérrez agency, identified on the photo along with the photographic company's name as Herlinda Perry in Ciudad Juárez in May 1911. She is shown holding a .30–30 carbine while seated on a low fence dressed in a skirt and blouse, with crossed bandoliers and two cartridge belts around her waist. So far, nothing further is known about her.[45] Another posed photo of Maderista soldaderas shown with bandoliers and rifles, with one Herlinda González in it. The women are well turned out in dresses. Two men flank the line of soldaderas, and two children also with bandoliers and rifles kneel in front of the group.[46] The founder of the Neutral White Cross, Elena Arizmendi Mejia was photographed as a soldadera, supposedly as a joke. She was already a prominent woman taking an active role in the revolution. The photo of her as a soldadera was published in the newspapers, and her antagonists attempted to use to say she was violating the neutrality of the medical organization.[47] However, José Guadalupe Posada made a lithograph from the photo and published it as the cover for corridos about the revolution, titling the image "La Maderista."[47][48]

Corridos

Corridos are ballads or folk songs that came around during the Mexican Revolution and started to gain popularity after the revolution. Most of these corridos were about soldaderas and originally were battle hymns, but now have been ways for soldaderas to gain some fame and be documented in history.[25] However, in most corridos, an aspect of love was part of the story line and in current day they became extremely romanticized.[49]

La Adelita

The most famous corrido is called "La Adelita", and was based on a woman who was a soldadera for Madero’s troops.[50] This corrido and the image of this woman became the symbol of the revolution and Adelita’s name has become synonymous with soldaderas. No one truly knows if the corrido based on this woman was a female soldier or a camp follower, or even perhaps that she was just a representation of a mix of different females that were a part of the revolution. Whatever the truth though, in Mexico and the U.S. today, Adelita has become an inspiration and a symbol for any woman who fights for her rights.

If you google "La Adelita Del Rio Texas" you will find that there is a grave in the San Felipe Cemetery with a headstone placed by the Mexican Consulate. It is claimed by the local newspaper and other sources to be the resting place of the woman who inspired the corrido (ballad).

[51] Many of the traditional corrido's praise her femininity, loyalty, and beauty instead of her valor and courage in battle.[52]

La Valentina

A lesser known corrido called "La Valentina" and was based on a female soldier named Valentina Ramirez that predates the Mexican revolution. Like La Adelita, La Valentina corrido became famous and prominent due to her femininity and not her valor in battle.[28]

Modern-day portrayals

Popular culture has changed the image of soldaderas throughout history, however, it has not been a static definition and has made the image ever-changing. Mass media in Mexico turned the female soldiers into heroines that sacrificed their lives for the revolution, and turned camp followers into nothing more than just prostitutes.[49] As a result, it made the idea of a female soldier synonymous with a soldadera and the idea of a camp follower was unimportant and therefore forgotten. However, with more recent popular culture, even the image of female soldiers has become sexualized. Images of female soldiers have become consumerist products portrayed as sexy females rather than portraying them as the revolutionary soldiers that they were.[53] The modern day images of soldaderas do not maintain the positive, worthy aspects of the real-life soldaderas from history.[54] However, images of soldaderas in popular culture are not always extremely sexualized. Adelita, now synonymous with a soldadera, has also become a part of children’s popular culture. Tomie dePaola wrote a children’s novel called Adelita, a Mexican Cinderella Story. The plot follows similarly to the original Cinderella story, but changes details so that the story fits into Mexican culture and norms. Adelita is the name of Cinderella and she has to have the courage to fight against the evil step mother and step sisters, and has to fight for the man that she falls in love with.[55] This may not portray soldaderas as fighting for rights, but she is fighting for something and not just a sexy pin-up style girl.

A believable soldadera and a female soldier were portrayed by Jenny Gago as the good-natured prostitute La Garduna in Old Gringo (1989) and Marie Gomez as the tough and passionate Lieut. Chiquita in The Professionals (1966).

Soldaderas have also regained some of their respect through the arts. The Ballet Folklórico de México did a U.S. tour in 2010 celebrating Mexico's history. When it came time to celebrate the Mexican Revolution, the ballet celebrated it only through the female soldiers.[56] As well, the image of soldaderas has also reverted to a symbol of fighting for women's rights for some adults. Especially for Mexican women and Americans in the United States that come from a Mexican heritage, the idea of a soldadera has gone back to the original meaning of the word and denotes a female soldier. For them, a soldadera holds a spirit of revolution[57] and has become a sort of role model for self-empowerment, especially for Mexican ancestry females in the United States as they are not just fighting as part of the minority of women, but also as part of the chicano minority.[58]

The fighting soldadera was adopted by the Chicano movement. The mindset of soldaderas being violent hot blooded revolutionaries or poor, pregnant camp followers persisted when depicting the soldadera. The Chicana feminist movement took the iconography of the soldaderas and made it their own. The brown berrets, a chicana female activism group calls them their inspiration. As well the Chicano movement latched onto them as well, but while women praised their valor, and courage in battle men praised their loyalty to their husbands, and nation further illustrating the machismo culture and the ideological split among the sexes.[58]

See also

- Index of Mexico-related articles

- Mexican Revolution

- Vivandière – French military canteen personnel

References

- ^ Gabriela Cano, "Soldaderas and Coronelas" in Encyclopedia of Mexico, vol. 1, pp. 1357–1360. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn 1997.

- ^ Friedrich Katz, The Life and Times of Pancho Villa. Stanford: Stanford University Press 1998, p. 290.

- ^ Cano, "Soldaderas and Coronelas" in Encyclopedia of Mexico, p. 1359.

- ^ a b c d e f Cano, "Soldaderas and Coronelas", p. 1359.

- ^ a b c Cano, "Soldaderas and Coronelas", p. 1358.

- ^ Frazer, Competing Voices from the Mexican Revolution: Fighting Words, 151.

- ^ Don M. Coerver, Suzanne B. Pasztor, Robert Buffington, "Mexico: an encyclopedia of contemporary culture and history", ABC-CLIO, 2004, p. 472.

- ^ Frazer, Chris (2010). Competing Voices from the Mexican Revolution: Fighting Words. Santa Barbara, California: Greenwood Press. p. 150. ISBN 9781846450372.

- ^ Salas, Elizabeth (1990). Soldaderas in the Mexican Military. Austin: University of Texas Press. p. xii. ISBN 0292776306.

- ^ a b c d e Katz, The Life and Times of Pancho Villa, p. 291.

- ^ Alan Knight, The Mexican Revolution, vol. 2: Counter-revolutionaries and Reconstruction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1986, p. 333.

- ^ Soto, Shirlene (1990). Emergence of the Modern Mexican Woman: Her Participation in Revolution and Struggle for Equality 1910–1940. Denver, Colorado: Arden Press, Inc. pp. 44. ISBN 0912869127.

- ^ Katz, The Life and Times of Pancho Villa, p. 290.

- ^ Knight, Mexican Revolution, vol. 2, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1986, p. 126.

- ^ Katz, Life and Times of Pancho Villa, p. 291.

- ^ Fuentes 1995, pp. 528–535.

- ^ Knight, Mexican Revolution, vol. 2, p. 143.

- ^ Knight, Mexican Revolution, vol. 2, p. 333.

- ^ Poniatowska 2006, p. 12.

- ^ Katz, The Life and Times of Pancho Villa, p. 628.

- ^ Katz, The Life and Times of Pancho Villa, pp. 891–892

- ^ Poniatowska 2006, p. 16.

- ^ Poniatowska 2006, p. 25.

- ^ Salas, Soldaderas in the Mexican Military, 47.

- ^ a b Soto, Emergence of the Modern Mexican Woman: Her Participation in Revolution and Struggle for Equality 1910–1940, 44.

- ^ a b John Reed, Insurgent Mexico(1914). New York: International Publishers 1969, p. 108.

- ^ Salas, Soldaderas in the Mexican Military, 40.

- ^ a b Fowler-Salamini, Heather; Vaughn, Mary Kay (1994). Women of the Countryside, 1850–1990. Tucson & London: The University of Arizona Press. p. 110. ISBN 0816514151.

- ^ Fowler-Salamini & Vaughn, Women of the Countryside, 1850–1990, 95.

- ^ a b Fernandez 2009, p. 55.

- ^ Fowler-Salamini & Vaughn, Women of the Countryside, 1850–1990, 95.

- ^ Fuentes 1995, p. 529.

- ^ a b Fernandez 2009, p. 56.

- ^ Fuentes 1995, pp. 542–543.

- ^ John Mraz, Photographing the Mexican Revolution, Austin: University of Texas Press 2012, p. 68.

- ^ Poniatowska 2006, p. 20.

- ^ Fuentes 1995, pp. 544–547.

- ^ Cano, "Soldaderas and Coronelas, p. 1359.

- ^ Cano, "Soldaderas and Coronelas, p. 1359

- ^ Salas, Soldaderas in the Mexican Military, 48.

- ^ Fowler-Salamini & Vaughn, Women of the Countryside, 1850–1990, 98.

- ^ Ivar Thord-Gray [Ivar Thord Hallström], Gringo Rebel: Mexico, 1913–1914. Coral Gables FL: University of Miami Press 1960, pp. 36–37, quoted in Katz, The Life and Times of Pancho Villa, p. 226.

- ^ quoted in Katz, The Life and Times of Pancho Villa, p. 304.

- ^ Reed, Insurgent Mexico, p. 111.

- ^ Mraz, Photographing the Mexican Revolution, pp. 68–69, photo 4–15.

- ^ Mraz, Photographing the Mexican Revolution, p. 70, photo 4–16.

- ^ a b Mraz, Photographing the Mexican Revolution, p. 70.

- ^ Gabriela Cano, Se llamaba Elena Arizmendi, Mexico City: Tusquets 2010, p. 131.

- ^ a b Fowler-Salamini & Vaughn, Women of the Countryside, 1850–1990, 102.

- ^ Soto, Emergence of the Modern Mexican Woman: Her Participation in Revolution and Struggle for Equality 1910–1940, 44.

- ^ Arrizon, Alicia (1998). ""Soldaderas" and the Staging of the Mexican Revolution". TDR. 42 (1). The MIT Press: 90–96. doi:10.1162/105420498760308698. JSTOR 1146648.

- ^ Salas, Elizabeth (1990). Soldaderas in the Mexican military: Myth and History. Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-292-77638-1.

- ^ Arrizon, ""Soldaderas" and the Staging of the Mexican Revolution", 108.

- ^ Fernandez 2009, p. 62.

- ^ "Adelita : A Mexican Cinderella Story". Publishers Weekly. Retrieved 2013-12-15.

- ^ "Mexico Tourism Board Promotes Ballet Folklórico de México U.S. Tour". Banderas News. March 5, 2010. Retrieved 2013-12-16.

- ^ Arrizon, ""Soldaderas" and the Staging of the Mexican Revolution", 109.

- ^ a b Salas, Elizabeth (1995). "Soldaderas: New Questions, New Sources". Women's Studies Quarterly. 23 (3/4). The Feminist Press at the City University of New York: 116. JSTOR 40003505.

Further reading

- Arce, B. Christine. Mexico's Nobodies: The Cultural Legacy of the Soldadera and Afro-Mexican Women. Albany: State University of New York Press 2016.

- Cano, Gabriela, "Soldaderas and Coronelas" in Encyclopedia of Mexico, vol. 2, pp. 1357–1360. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn 1997.

- Fernandez, Delia (2009). "From Soldadera to Adelita: The Depiction of Women in the Mexican Revolution". McNair Scholars Journal. 13 (1). Grand Valley State University: 55.

Popular images of women during the Mexican Revolution (1911–1920) often depict them as dressed provocatively, yet wearing a bandolier and gun. Although the image is common, its origin is not well known. An examination of secondary literature and media will show the transformation in the image of the female soldier (soldadera) over the course of the Revolution from that of the submissive follower into a promiscuous fighter (Adelita). The soldaderas exhibited masculine characteristics, like strength and valor, and for these attributes, men were responsible for reshaping the soldadera's image into the ideal (docile, yet licentious) woman of the time.

- Leland, Maria. Separate Spheres: Soldaderas and Feminists in Revolutionary Mexico. Columbus: Ohio State University Press 2010.

- Macias, Anna (1980). "Women and the Mexican Revolution". The Americas 37 (1).

- Mendieta Alatorre, Angeles. La Mujer en la Revolución Mexicana. Mexico City: Instituto Nacional de Estudios Históricos de la Revolución Mexicana, 1961.

- Poniatowska, Elena (2006). Las Soldaderas: Women of the Mexican Revolution. Cinco Puntos Press. ISBN 1933693045.

- Reséndez, Andrés (April 1995). "Battleground Women: Soldaderas and Female Soldiers in the Mexican Revolution". The Americas. 51 (4): 525–553. doi:10.2307/1007679. JSTOR 1007679.

- Ruiz-Alfaro, Sofia (2013). "A Threat to the Nation: México Marimacho and Female Masculinities in Postrevolutionary Mexico." Hispanic Review 81 (1): 41–62.

- Salas, Elizabeth. Soldaderas in the Mexican Military: Myth and History. Austin: University of Texas Press 1990.