Solar eclipse of May 29, 1919

| Solar eclipse of May 29, 1919 | |

|---|---|

From the report of Sir Arthur Eddington on the expedition to the island of Principe (off the west coast of Africa). | |

| Type of eclipse | |

| Nature | Total |

| Gamma | −0.2955 |

| Magnitude | 1.0719 |

| Maximum eclipse | |

| Duration | 411 s (6 min 51 s) |

| Coordinates | 4°24′N 16°42′W / 4.4°N 16.7°W |

| Max. width of band | 244 km (152 mi) |

| Times (UTC) | |

| Greatest eclipse | 13:08:55 |

| References | |

| Saros | 136 (32 of 71) |

| Catalog # (SE5000) | 9326 |

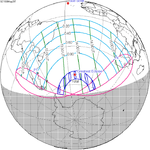

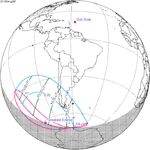

A total solar eclipse occurred at the Moon's descending node of orbit on Thursday, May 29, 1919,[1] with a magnitude of 1.0719. A solar eclipse occurs when the Moon passes between Earth and the Sun, thereby totally or partly obscuring the image of the Sun for a viewer on Earth. A total solar eclipse occurs when the Moon's apparent diameter is larger than the Sun's, blocking all direct sunlight, turning day into darkness. Totality occurs in a narrow path across Earth's surface, with the partial solar eclipse visible over a surrounding region thousands of kilometres wide. Occurring only 19 hours after perigee (on May 28, 1919, at 18:09 UTC), the Moon's apparent diameter was larger.[2]

This specific total solar eclipse was significant because it helped prove Einstein's theory of relativity.[3] The eclipse was the subject of the Eddington experiment: two groups of British astronomers went to Brazil and the west coast of Africa to take pictures of the stars in the sky once the Moon covered the Sun and darkness was revealed.[3] Those photos helped prove that the Sun interferes with the bend of starlight.[3]

The totality of this eclipse was visible from southeastern Peru, northern Chile, much of Bolivia and central Brazil, southern Liberia, the southern Ivory Coast, Principe, Río Muni (now Equatorial Guinea), parts of central French Equatorial Africa (now Gabon and the Republic of the Congo), Belgian Congo (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo), northern Rhodesia (now northern Zambia), German East Africa (now Tanzania), northern Nyasaland (now Malawi), northern Mozambique, and the western Comoros. A partial eclipse was visible for most of South America and Africa.

Observations and locations

A total solar eclipse occurred on Thursday, May 29, 1919. With the duration of totality at maximum eclipse of 6 minutes 50.75 seconds, it was the longest solar eclipse that occurred since May 27, 1416. A longer total solar eclipse would later occur on June 8, 1937.

It was visible throughout most of South America and Africa as a partial eclipse. Totality occurred through a narrow path across southeastern Peru, northern Chile, central Bolivia and Brazil after sunrise, across the Atlantic Ocean and into south central Africa, covering southern Liberia, southern French West Africa (the part now belonging to Ivory Coast), the southwestern tip of the British Gold Coast (now Ghana), Príncipe Island in Portuguese São Tomé and Príncipe, southern Spanish Guinea (now Equatorial Guinea), French Equatorial Africa (the parts now belonging to Gabon and R. Congo, including Libreville), Belgian Congo (now DR Congo), northeastern Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia), the northern tip of Nyasaland (now Malawi), German East Africa (now belonging to Tanzania) and northeastern Portuguese Mozambique (now Mozambique), ending near sunset in eastern Africa.

Planets and stars visible during totality

The Sun was at about its nearest to Aldebaran, so that star was potentially visible throughout the eclipse path. Mars had its conjunction with the Sun twenty days earlier and shone at 2nd magnitude a few degrees to the west. Much brighter Mercury was several degrees farther west of the Sun than Mars. Those were the only two bright planets visible in Bolivia, where the eclipsed Sun was very low in the east. Deneb, Altair, Fomalhaut and Achernar were the only 1st-magnitude stars well clear of the horizon; Vega, Aldebaran, Rigel and Canopus were very low. Observers in western Africa had a much more impressive eclipse sky with the Winter Hexagon well up, along with Canopus. Venus and Jupiter were brilliant near Pollux and Saturn was close to the west of Regulus.[4]

Connection to the general theory of relativity

Newton's laws of physics ran on the belief of absolute time and three dimensions of space.[5] This idea meant that time had only one dimension, and that it was universal.[5][6] Einstein had the idea of combining space and time to make a four-dimensional world that worked together.[7][8] Einstein's idea meant that extremely small matter particles could produce massive amounts of energy.[7] If Einstein's theory was correct, matter and radiation would be connected to energy and momentum,[9] meaning that when light was passing a large mass there would be an observable bend to the light.[9]

Einstein's prediction of the bending of light by the gravity of the Sun, one of the components of his general theory of relativity, can be tested during a solar eclipse, when stars with apparent position near the Sun become visible. The stars cannot be seen without a solar eclipse because stars passing the sun are drowned by solar glares.[10]

Following an unsuccessful attempt to validate this prediction during the Solar eclipse of June 8, 1918,[11] two expeditions were made to measure positions of stars during this eclipse (see Eddington experiment). They were organized under the direction of Sir Frank Watson Dyson. One expedition was led by Sir Arthur Eddington to the island of Príncipe (off the west coast of Africa), the other by Andrew Claude de la Cherois Crommelin and Charles Rundle Davidson to Sobral in Brazil.[12][13][14] The stars that both expeditions observed, the Hyades, were in the constellation Taurus.[15]

The solar eclipse of May 29, 1919 allowed Einstein to finalize his theory of relativity.[16] However, the May eclipse was almost missed, due to unexpected storms.[17] The astronomers were almost unable to get photos of this eclipse due to a cloud.[18][17] A thunderstorm happened during the morning of the eclipse, and it had been overcast that day and many of the days beforehand.[18][17] Only thirty minutes before the eclipse did the clouds begin to dissipate, and even then they were taking many photos through gaps in the clouds.[17]

The photographs taken during the eclipse of May 29, 1919, proved Einstein correct and changed ideas of physics.[19] They also provided evidence that the Sun's mass did shift the way a star's light will bend.[16] From the findings from these expeditions Dyson is quoted saying, "After a careful study of the plates, I am prepared to say that they confirm Einstein's prediction."[19] He continued to explain that it left little doubt about light deflection in the area around the Sun and it was the amount Einstein demanded in his generalized theory of relativity.[19]

Eclipse details

Shown below are two tables displaying details about this particular solar eclipse. The first table outlines times at which the moon's penumbra or umbra attains the specific parameter, and the second table describes various other parameters pertaining to this eclipse.[20]

| Event | Time (UTC) |

|---|---|

| First Penumbral External Contact | 1919 May 29 at 10:33:42.1 UTC |

| First Umbral External Contact | 1919 May 29 at 11:28:47.1 UTC |

| First Central Line | 1919 May 29 at 11:30:18.1 UTC |

| First Umbral Internal Contact | 1919 May 29 at 11:31:49.2 UTC |

| First Penumbral Internal Contact | 1919 May 29 at 12:31:38.1 UTC |

| Equatorial Conjunction | 1919 May 29 at 13:06:48.8 UTC |

| Greatest Eclipse | 1919 May 29 at 13:08:54.5 UTC |

| Greatest Duration | 1919 May 29 at 13:09:53.0 UTC |

| Ecliptic Conjunction | 1919 May 29 at 13:11:55.6 UTC |

| Last Penumbral Internal Contact | 1919 May 29 at 13:46:13.7 UTC |

| Last Umbral Internal Contact | 1919 May 29 at 14:46:02.6 UTC |

| Last Central Line | 1919 May 29 at 14:47:32.7 UTC |

| Last Umbral External Contact | 1919 May 29 at 14:49:02.7 UTC |

| Last Penumbral External Contact | 1919 May 29 at 15:44:10.0 UTC |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Eclipse Magnitude | 1.07186 |

| Eclipse Obscuration | 1.14889 |

| Gamma | −0.29549 |

| Sun Right Ascension | 04h21m07.3s |

| Sun Declination | +21°30'15.9" |

| Sun Semi-Diameter | 15'46.6" |

| Sun Equatorial Horizontal Parallax | 08.7" |

| Moon Right Ascension | 04h21m12.6s |

| Moon Declination | +21°12'18.4" |

| Moon Semi-Diameter | 16'38.3" |

| Moon Equatorial Horizontal Parallax | 1°01'03.7" |

| ΔT | 21.0 s |

Eclipse season

This eclipse is part of an eclipse season, a period, roughly every six months, when eclipses occur. Only two (or occasionally three) eclipse seasons occur each year, and each season lasts about 35 days and repeats just short of six months (173 days) later; thus two full eclipse seasons always occur each year. Either two or three eclipses happen each eclipse season. In the sequence below, each eclipse is separated by a fortnight.

| May 15 Ascending node (full moon) |

May 29 Descending node (new moon) |

|---|---|

|

|

| Penumbral lunar eclipse Lunar Saros 110 |

Total solar eclipse Solar Saros 136 |

Related eclipses

Earlier eclipses related to the Theory of Relativity

Before 1919 there were two eclipses in 1912 where this idea was almost proven, but there were outside factors against astronomers.[21] The first eclipse in 1912 was on April 17, but superstition, underfunding, and time overwhelmed the astronomers on this date.[22] The April 17 eclipse was nicknamed "The Titanic Eclipse", because it occurred two days after the sinking of the Titanic.[22] There is a history of people connecting eclipses to "divine events", and due to the continued search and rescue of victims, people started to believe that the eclipse and wreck were connected.[22] The surrounding superstition of the eclipse led to it being less a study on physics and more of a party.[22] However, a lack of funding, preparation, and time of total coverage of the sun would have also caused issues for the astronomers.[22] The second eclipse they wanted to photograph was on October 10, 1912, and it was unable to be photographed due to rain.[22]

Eclipses in 1919

- A penumbral lunar eclipse on May 15.

- A total solar eclipse on May 29.

- A partial lunar eclipse on November 7.

- An annular solar eclipse on November 22.

Metonic

- Preceded by: Solar eclipse of August 10, 1915

- Followed by: Solar eclipse of March 17, 1923

Tzolkinex

- Preceded by: Solar eclipse of April 17, 1912

- Followed by: Solar eclipse of July 9, 1926

Half-Saros

- Preceded by: Lunar eclipse of May 24, 1910

- Followed by: Lunar eclipse of June 3, 1928

Tritos

- Preceded by: Solar eclipse of June 28, 1908

- Followed by: Solar eclipse of April 28, 1930

Solar Saros 136

- Preceded by: Solar eclipse of May 18, 1901

- Followed by: Solar eclipse of June 8, 1937

Inex

- Preceded by: Solar eclipse of June 17, 1890

- Followed by: Solar eclipse of May 9, 1948

Triad

- Preceded by: Solar eclipse of July 27, 1832

- Followed by: Solar eclipse of March 29, 2006

Solar eclipses of 1916–1920

This eclipse is a member of a semester series. An eclipse in a semester series of solar eclipses repeats approximately every 177 days and 4 hours (a semester) at alternating nodes of the Moon's orbit.[23]

The solar eclipses on February 3, 1916 (total), July 30, 1916 (annular), January 23, 1917 (partial), and July 19, 1917 (partial) occur in the previous lunar year eclipse set.

| Solar eclipse series sets from 1916 to 1920 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ascending node | Descending node | |||||

| Saros | Map | Gamma | Saros | Map | Gamma | |

| 111 | December 24, 1916 Partial |

−1.5321 | 116 | June 19, 1917 Partial |

1.2857 | |

| 121 | December 14, 1917 Annular |

−0.9157 | 126 | June 8, 1918 Total |

0.4658 | |

| 131 | December 3, 1918 Annular |

−0.2387 | 136 Totality in Príncipe |

May 29, 1919 Total |

−0.2955 | |

| 141 | November 22, 1919 Annular |

0.4549 | 146 | May 18, 1920 Partial |

−1.0239 | |

| 151 | November 10, 1920 Partial |

1.1287 | ||||

Saros 136

This eclipse is a part of Saros series 136, repeating every 18 years, 11 days, and containing 71 events. The series started with a partial solar eclipse on June 14, 1360. It contains annular eclipses from September 8, 1504 through November 12, 1594; hybrid eclipses from November 22, 1612 through January 17, 1703; and total eclipses from January 27, 1721 through May 13, 2496. The series ends at member 71 as a partial eclipse on July 30, 2622. Its eclipses are tabulated in three columns; every third eclipse in the same column is one exeligmos apart, so they all cast shadows over approximately the same parts of the Earth.

The longest duration of annularity was produced by member 9 at 32 seconds on September 8, 1504, and the longest duration of totality was produced by member 34 at 7 minutes, 7.74 seconds on June 20, 1955. All eclipses in this series occur at the Moon’s descending node of orbit.[24]

| Series members 26–47 occur between 1801 and 2200: | ||

|---|---|---|

| 26 | 27 | 28 |

March 24, 1811 |

April 3, 1829 |

April 15, 1847 |

| 29 | 30 | 31 |

April 25, 1865 |

May 6, 1883 |

May 18, 1901 |

| 32 | 33 | 34 |

May 29, 1919 |

June 8, 1937 |

June 20, 1955 |

| 35 | 36 | 37 |

June 30, 1973 |

July 11, 1991 |

July 22, 2009 |

| 38 | 39 | 40 |

August 2, 2027 |

August 12, 2045 |

August 24, 2063 |

| 41 | 42 | 43 |

September 3, 2081 |

September 14, 2099 |

September 26, 2117 |

| 44 | 45 | 46 |

October 7, 2135 |

October 17, 2153 |

October 29, 2171 |

| 47 | ||

November 8, 2189 | ||

Metonic series

The metonic series repeats eclipses every 19 years (6939.69 days), lasting about 5 cycles. Eclipses occur in nearly the same calendar date. In addition, the octon subseries repeats 1/5 of that or every 3.8 years (1387.94 days). All eclipses in this table occur at the Moon's descending node.

| 22 eclipse events between March 16, 1866 and August 9, 1953 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| March 16–17 | January 1–3 | October 20–22 | August 9–10 | May 27–29 |

| 108 | 110 | 112 | 114 | 116 |

March 16, 1866 |

August 9, 1877 |

May 27, 1881 | ||

| 118 | 120 | 122 | 124 | 126 |

March 16, 1885 |

January 1, 1889 |

October 20, 1892 |

August 9, 1896 |

May 28, 1900 |

| 128 | 130 | 132 | 134 | 136 |

March 17, 1904 |

January 3, 1908 |

October 22, 1911 |

August 10, 1915 |

May 29, 1919 |

| 138 | 140 | 142 | 144 | 146 |

March 17, 1923 |

January 3, 1927 |

October 21, 1930 |

August 10, 1934 |

May 29, 1938 |

| 148 | 150 | 152 | 154 | |

March 16, 1942 |

January 3, 1946 |

October 21, 1949 |

August 9, 1953 | |

Tritos series

This eclipse is a part of a tritos cycle, repeating at alternating nodes every 135 synodic months (≈ 3986.63 days, or 11 years minus 1 month). Their appearance and longitude are irregular due to a lack of synchronization with the anomalistic month (period of perigee), but groupings of 3 tritos cycles (≈ 33 years minus 3 months) come close (≈ 434.044 anomalistic months), so eclipses are similar in these groupings.

| Series members between 1801 and 2200 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

April 4, 1810 (Saros 126) |

March 4, 1821 (Saros 127) |

February 1, 1832 (Saros 128) |

December 31, 1842 (Saros 129) |

November 30, 1853 (Saros 130) |

October 30, 1864 (Saros 131) |

September 29, 1875 (Saros 132) |

August 29, 1886 (Saros 133) |

July 29, 1897 (Saros 134) |

June 28, 1908 (Saros 135) |

May 29, 1919 (Saros 136) |

April 28, 1930 (Saros 137) |

March 27, 1941 (Saros 138) |

February 25, 1952 (Saros 139) |

January 25, 1963 (Saros 140) |

December 24, 1973 (Saros 141) |

November 22, 1984 (Saros 142) |

October 24, 1995 (Saros 143) |

September 22, 2006 (Saros 144) |

August 21, 2017 (Saros 145) |

July 22, 2028 (Saros 146) |

June 21, 2039 (Saros 147) |

May 20, 2050 (Saros 148) |

April 20, 2061 (Saros 149) |

March 19, 2072 (Saros 150) |

February 16, 2083 (Saros 151) |

January 16, 2094 (Saros 152) |

December 17, 2104 (Saros 153) |

November 16, 2115 (Saros 154) |

October 16, 2126 (Saros 155) |

September 15, 2137 (Saros 156) |

August 14, 2148 (Saros 157) |

July 15, 2159 (Saros 158) |

June 14, 2170 (Saros 159) |

May 13, 2181 (Saros 160) |

April 12, 2192 (Saros 161) | ||||

Inex series

This eclipse is a part of the long period inex cycle, repeating at alternating nodes, every 358 synodic months (≈ 10,571.95 days, or 29 years minus 20 days). Their appearance and longitude are irregular due to a lack of synchronization with the anomalistic month (period of perigee). However, groupings of 3 inex cycles (≈ 87 years minus 2 months) comes close (≈ 1,151.02 anomalistic months), so eclipses are similar in these groupings.

| Series members between 1801 and 2200 | ||

|---|---|---|

August 17, 1803 (Saros 132) |

July 27, 1832 (Saros 133) |

July 8, 1861 (Saros 134) |

June 17, 1890 (Saros 135) |

May 29, 1919 (Saros 136) |

May 9, 1948 (Saros 137) |

April 18, 1977 (Saros 138) |

March 29, 2006 (Saros 139) |

March 9, 2035 (Saros 140) |

February 17, 2064 (Saros 141) |

January 27, 2093 (Saros 142) |

January 8, 2122 (Saros 143) |

December 19, 2150 (Saros 144) |

November 28, 2179 (Saros 145) |

|

Notes

- ^ "May 29, 1919 Total Solar Eclipse". timeanddate. Retrieved 1 August 2024.

- ^ "Moon Distances for London, United Kingdom, England". timeanddate. Retrieved 1 August 2024.

- ^ a b c Cowen, Ron (2019). Gravity's Century (1st ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts. London, England: Harvard University Press. pp. 2–3. ISBN 9780674974968.

- ^ https://skyandtelescope.org/interactive-sky-chart/ Sky & Telescope Interactive Sky Chart

- ^ a b Gates, Sylvester J.; Pelletier, Cathie (2019). Proving Einstein right: the daring expeditions that changed how we look at the universe (1st ed.). New York: PublicAffairs. ISBN 978-1-5417-6225-1.

- ^ Dvorak, John (2017). Mask of the sun: the science, history, and forgotten lore of eclipses. New York, NY: Pegasus Books Ltd. ISBN 978-1-68177-330-8. OCLC 951925837.

- ^ a b Gates, Sylvester J.; Pelletier, Cathie (2019). Proving Einstein right: the daring expeditions that changed how we look at the universe (1st ed.). New York: PublicAffairs. ISBN 978-1-5417-6225-1.

- ^ Dvorak, John (2017). Mask of the sun: the science, history, and forgotten lore of eclipses. New York, NY: Pegasus Books Ltd. ISBN 978-1-68177-330-8. OCLC 951925837.

- ^ a b Gates, Sylvester J.; Pelletier, Cathie (2019). Proving Einstein right: the daring expeditions that changed how we look at the universe (1st ed.). New York: PublicAffairs. ISBN 978-1-5417-6225-1.

- ^ Steel, Duncan (2001). Eclipse (1st ed.). Washington, D.C.: The Joseph Henry Press. pp. 112–113. ISBN 0-309-07438-X.

- ^ Ethan Siegel, "America's Previous Coast-To-Coast Eclipse Almost Proved Einstein Right", Forbes, Aug 4, 2017. Retrieved August 4, 2017.

- ^ ”Eclipse 1919”, Web site commemorating the 1919 Solar Eclipse expedition, 2019. Retrieved December 10, 2021.

- ^ Longair, Malcolm (2015-04-13). "Bending space–time: a commentary on Dyson, Eddington and Davidson (1920) 'A determination of the deflection of light by the Sun's gravitational field'". Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A. 373 (2039): 20140287. Bibcode:2015RSPTA.37340287L. doi:10.1098/rsta.2014.0287. ISSN 1364-503X. PMC 4360090. PMID 25750149.

- ^ Kennefick, Daniel (2019). No Shadow of a Doubt. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-18386-2.

- ^ F. W. Dyson; A. S. Eddington; C. Davidson (1920). "A Determination of the Deflection of Light by the Sun's Gravitational Field, from Observations Made at the Total Eclipse of May 29, 1919". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. CCXX-A 579 (571–581): 291–333. Bibcode:1920RSPTA.220..291D. doi:10.1098/rsta.1920.0009.

- ^ a b Cowen, Ron (2019). Gravity's Century (1st ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts. London, England: Harvard University Press. pp. 2–3. ISBN 9780674974968.

- ^ a b c d Kennefick, Daniel (2019). No shadow of a doubt: the 1919 eclipse that confirmed Einstein's theory of relativity. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-18386-2. OCLC 1051138098.

- ^ a b Gates, Sylvester J.; Pelletier, Cathie (2019). Proving Einstein right: the daring expeditions that changed how we look at the universe (1st ed.). New York: PublicAffairs. ISBN 978-1-5417-6225-1.

- ^ a b c Dvorak, John J. (2017). Mask of the sun: the science, history, and forgotten lore of eclipses. New York (N.Y.): Pegasus Books ltd. ISBN 978-1-68177-330-8.

- ^ "Total Solar Eclipse of 1919 May 29". EclipseWise.com. Retrieved 1 August 2024.

- ^ Kennefick, Daniel (2019). No shadow of a doubt: the 1919 eclipse that confirmed Einstein's theory of relativity. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-18386-2. OCLC 1051138098.

- ^ a b c d e f Gates, Sylvester J.; Pelletier, Cathie (2019). Proving Einstein right: the daring expeditions that changed how we look at the universe (1st ed.). New York: PublicAffairs. ISBN 978-1-5417-6225-1.

- ^ van Gent, R.H. "Solar- and Lunar-Eclipse Predictions from Antiquity to the Present". A Catalogue of Eclipse Cycles. Utrecht University. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- ^ "NASA - Catalog of Solar Eclipses of Saros 136". eclipse.gsfc.nasa.gov.