Soapy Smith

Soapy Smith | |

|---|---|

Smith at bar in Skagway, Alaska, 1898 | |

| Born | Jefferson Randolph Smith II November 2, 1860 Coweta County, Georgia, U.S. |

| Died | July 8, 1898 (aged 37) |

| Cause of death | Gunshot wounds |

| Occupation(s) | Con artist, gangster, gambler, saloon proprietor, political boss |

| Spouse | Mary Eva Noonan |

| Children | Jefferson Randolph Smith III, Mary Eva Smith, James Luther Smith |

| Parent(s) | Jefferson Randolph Smith I Emily Dawson Edmondson |

Jefferson Randolph "Soapy" Smith II (November 2, 1860 – July 8, 1898) was an American con artist and gangster in the American frontier and the Klondike.

Smith operated confidence schemes across the Western United States, and had a large hand in organized criminal operations in both Colorado and the District of Alaska. Smith gained notoriety through his "prize soap racket," in which he would sell bars of soap with prize money hidden in some of the bars' packaging in order to increase sales. However, through sleight of hand, he ensured that only members of his gang purchased "prize" soap. The racket led to his sobriquet of "Soapy."

The success of his soap racket and other scams helped him finance three successive criminal empires in Denver and Creede, both in Colorado, and in Skagway, Alaska. He was killed in the shootout on Juneau Wharf in Skagway, on July 8, 1898.

Early years

Jefferson Smith was born on November 2, 1860, in Coweta County, Georgia, to a wealthy family. His grandfather was a plantation owner and Georgia legislator, while his father was an attorney.[1][2] However, the Smith family was met with financial ruin at the close of the American Civil War and in 1876, they moved to Round Rock, Texas, to start anew. It was in Round Rock where Smith began his career as a confidence man.[3] In 1877, Smith's mother died and he left home shortly thereafter, but not before witnessing the death of the outlaw Sam Bass in 1878.[1]

Career

Smith moved to Fort Worth, Texas, where he formed a close-knit, disciplined gang of shills and thieves to work for him. He quickly became a well-known crime boss and, eventually, the "king of the frontier con men."[4] His gang of swindlers, known as the Soap Gang, including men such as Texas Jack Vermillion and "Big Ed" Burns, moved from town to town plying their trade on unwary victims.[4][5] Their principal method was short cons, in which swindles were quick and needed little setup and assistance. The short cons included the shell game, three-card monte, and rigged poker games, which they called "big mitt."[6]

The prize soap racket

Smith's most well-known short con was a ploy which the Denver newspapers dubbed the "prize soap racket."[7] Smith would set a display case, piled with bars of soap, on a busy street corner. As he sold the bars of soap and spoke to a growing crowd of onlookers, he would wrap money—ranging from one to a hundred dollars—around a few select bars of soap. He then wrapped plain paper around all the bars so that the money was hidden.

He then made the appearance of mixing the money-wrapped "prize soap" in with the regular soap and sold the soap to the crowd for one dollar per bar. Then, a shill in the crowd would buy a bar, tear it open, and loudly proclaim that he had won some money, waving it around for all to see. The performance led to the sale of even more bars of soap. Midway through the sale, Smith would announce that the hundred-dollar bill still remained in the pile. He would then auction off the remaining soap bars to the highest bidders.[8] Through manipulation and sleight-of-hand, the only money "won" went to his shills.[9]

On one occasion, Smith was arrested by policeman John Holland for running his prize soap racket. While writing in the police logbook, Holland had forgotten Smith's first name and wrote "Soapy."[10] The sobriquet stuck, and he became known as "Soapy Smith."

Denver, Colorado

In 1879, Smith arrived in Denver for the first time and, by 1882, he had successfully built the first of his three empires. Con men usually moved from town to town to avoid the law, but as Smith's power and gang grew, so did his influence at city hall, which allowed him to remain in the city, protected from prosecution. By 1887, he was reputedly involved with most of the criminal activities in the city. Newspapers in Denver reported that he controlled the city's criminals and underworld gambling, and accused corrupt politicians and the police chief of accepting bribes.[11]

The Tivoli Club

In 1888, Smith opened The Tivoli Club—a combination saloon and gambling house—on the southeast corner of Market and 17th Street. Allegedly, a sign above the entrance to the gambling games read "caveat emptor," Latin for "let the buyer beware."[12] Smith's younger brother, Bascomb Smith, joined the gang and operated a cigar store that was a front for dishonest poker games and other swindles, which operated in one of the back rooms.[13] Other operations included fraudulent lottery shops, a "sure thing" stock exchange, fake watch and diamond auctions, and the sale of stocks in nonexistent businesses.

Politics and other cons

Due to receiving bribes, some of the police officers patrolling the streets would not arrest Smith or members of his gang, and other officers feared Smith's quick and violent anger. On those occasions when Smith or one of his men were arrested, their friends, attorneys, and associates were always ready to obtain their quick release from jail. An electoral fraud trial after the municipal elections of 1889 brought attention to the corrupt ties and payoffs among Smith, the mayor and the chief of police—a combination referred to in local newspapers as "the firm of Londoner, Farley, and Smith."[14] The mayor lost his job, but Smith remained untouched. He opened an office in the prominent Cheever block (one block south of his Tivoli Club) from which he ran his many operations. This also fronted as a business tycoon's office for high-end swindles.[15]

Smith was not without enemies and rivals for his position as underworld boss. He faced several attempts on his life and shot several of his assailants. He became known increasingly for his gambling and bad temper.[citation needed]

Creede, Colorado

In 1892, with Denver in the midst of anti-gambling and saloon reforms, Smith sold the Tivoli and moved to Creede, Colorado, a mining boomtown that sprang up on the site of a major silver strike. Using Denver-based prostitutes to get close to property owners and convince them to sign over leases, he acquired numerous lots along Creede's main street and rented them to his associates.[16] After gaining enough allies, he announced that he was the camp boss.[citation needed]

With brother-in-law and gang member William Sidney "Cap" Light as a deputy sheriff, Smith began his second empire, opening a gambling hall and saloon called the Orleans Club.[17] He purchased and briefly exhibited a petrified man nicknamed "McGinty" for an admission of 10 cents. While customers were waiting in line, Smith ran shell and three-card monte games to swindle even more money.[18]

Smith provided an order of sorts, protecting his friends and associates from the town's council and expelling violent troublemakers. Many of the influential newcomers were sent to meet him. Smith grew rich in the process but was also known to give money away freely, using it to build churches, help the poor, and to bury unfortunate prostitutes.[citation needed]

Creede's boom quickly waned, and corrupt Denver officials sent word that the reforms in Denver were coming to an end. Smith returned to Denver and brought "McGinty" with him. He left at the right time, as Creede soon lost most of its business district in a huge fire on 5 June 1892. Among the buildings destroyed was the Orleans Club.[19]

Return to Denver, Colorado

Upon his return to Denver, Smith opened new businesses which served as fronts for his many short cons. One involved allegedly discounted railroad tickets, in which potential purchasers were told the ticket agent was out of the office, but that they could benefit from a discount by playing any of several rigged games.[20] Smith's power had grown to the point that he admitted to the press he was a con man and saw nothing wrong with it, telling a reporter, "I consider bunco steering more honorable than the life led by the average politician."[21]

In 1894, Colorado's newly-elected governor Davis Hanson Waite fired three Denver officials as part of anti-corruption reforms. They refused to leave their positions and fortified themselves in the Denver City Hall with others who felt their jobs were threatened. Governor Waite called on the state militia to remove them, which brought two cannons and two Gatling guns. Smith joined the corrupt officeholders and police at City Hall and was commissioned a deputy sheriff. Smith and several of his men climbed the City Hall's central tower with rifles and dynamite to fend off any attackers.[22] However, Governor Waite eventually decided to withdraw the militia and the battle was instead fought in the courts, in which Soapy Smith was an important witness. The Colorado Supreme Court ruled that Governor Waite had authority to replace the commissioners, but was to be reprimanded for bringing in the militia, in what became known as the "City Hall War."[23]

Governor Waite then ordered the closure of all of Denver's gambling dens, saloons, and bordellos. Smith exploited the situation, using his new title of deputy sheriff to make fake arrests in his own gambling houses by apprehending patrons who had lost large sums in rigged poker games.[24] The victims were happy to leave when the "officers" allowed them to walk away from the crime scene—without recouping their losses—rather than be arrested.

Eventually, Soapy and his brother Bascomb Smith became too well-known, and even the most corrupt city officials could no longer protect them. When they were charged with attempted murder for the beating of a saloon manager, Bascomb was jailed but Soapy managed to escape, becoming a wanted man in Colorado.

Before leaving, Smith tried to convince the Mexican President Porfirio Díaz that his country needed the services of a foreign legion made up of American toughs. Smith became known as Colonel Smith, and managed to organize a recruiting office before the deal failed.[25]

Skagway and the Klondike Gold Rush

When the Klondike Gold Rush began in 1897, Smith moved his operations to Skagway.[26] His first attempt at occupying Skagway ended in failure when miners' committees encouraged him to leave the area after operating his three-card monte and pea-and-shell games on the White Pass Trail for less than a month. He traveled to St. Louis and Washington, D.C., and did not return to Skagway until late January 1898.[27]

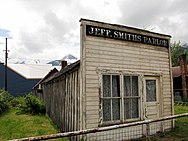

Smith set up his third empire much the same way as he had in Denver and Creede.[28] He put the town's deputy U.S. marshal on his payroll and began collecting allies for a takeover.[29] Smith opened a fake telegraph office in which the wires went only as far as the wall. Not only did the telegraph office obtain fees for "sending" messages, but also cash-laden victims soon found themselves losing even more money in poker games with newfound "friends."[30] Telegraph lines did not reach or leave Skagway until 1901.[31] Smith opened a saloon named Jeff. Smith's Parlor in March 1898 as an office from which to run his operations.[32][33] Although Skagway already had a municipal building, Smith's saloon became known as "the real city hall."

Smith's men played a variety of roles, such as newspaper reporter or clergyman, with the intention of befriending a new arrival and determining the best way to rid him of his money. The new arrival would be steered by his "friends" to dishonest shipping companies, hotels, or gambling dens until he was wiped out. If the man was likely to make trouble or could not be recruited into the gang, Smith would then appear in person and offer to pay his way back to civilization.[34]

When a vigilance committee, the "Committee of 101," threatened to expel Smith and his gang, he formed his own "law and order society," which claimed 317 members, to force the vigilantes into submission.[35] Most of the petty gamblers and con men did indeed leave Skagway at this time, and Smith resorted to other means to appear respectable to the community.[36]

During the Spanish–American War in 1898, Smith formed his own volunteer army with the approval of the United States Department of War, known as the "Skaguay Military Company," with himself as its captain. Smith wrote to President William McKinley and gained official recognition for his company, which he used to strengthen his control of the town.[37]

On July 4, 1898, Smith rode as marshal of the Fourth Division of the parade leading his army on his gray horse. On the grandstand, he sat beside the territorial governor and other officials.

Death

On July 7, 1898, John Douglas Stewart, a returning Klondike miner, came to Skagway with a sack of gold valued at $2,700 (equivalent to $98,900 in 2023). Three gang members convinced the miner to participate in a game of three-card monte. When Stewart balked at having to pay his losses, the three men grabbed the sack and ran. The "Committee of 101" demanded that Smith return the gold, but he refused, claiming that Stewart had lost it "fairly."

On the evening of July 8, the vigilance committee organized a meeting on the Juneau Wharf. With a Winchester rifle draped over his shoulder, Smith began an argument with Frank H. Reid, one of four guards blocking his way to the wharf. A gunfight, known as the Shootout on Juneau Wharf, began unexpectedly, and both men were fatally wounded.

Smith's last words were "My God, don't shoot!"[38] A letter from Sam Steele, the legendary head of the Canadian Mounties at the time, indicates that another guard, Jesse Murphy, may have fired the fatal shot.[39] Smith died on the spot with a bullet to the heart. He also received a bullet in his left leg and a severe wound on the left arm by the elbow. Reid died 12 days later with a bullet in his leg and groin area. The three gang members who robbed Stewart received jail sentences.

Soapy Smith was buried several yards outside the city cemetery.

Legacy and portrayals

Festivals

- Soapy Smith Wake in Skagway, Alaska. Held annually on July 8.

- Soapy Smith Party at the Magic Castle in Hollywood. An annual party on July 8 with costume contests, charity gambling, and magic shows.

Fiction

- You Can't Win (1926), Smith appears in Jack Black's autobiography.[40]

- Yukon Gold (1977), Smith appears as the main villain, in William D. Blankenship's novel.[41]

- The Great Alone (1987), Smith is a major character in the novel by Janet Dailey.[42]

- The Yukon Trail (1994), a video game where the player can meet Soapy Smith and play his shell game featured in "The Wretched Hive".[43]

- The King of the Klondike (1995) (Uncle Scrooge #292, part 8 of The Life and Times of Scrooge McDuck), Soapy Slick is the crooked saloon operator and profiteer in the Uncle Scrooge comic series.[44]

- How Much for Just the Planet? (2000), in the Star Trek Worlds Apart novel by John M. Ford, a 1987 Star Trek tie-in novel, a small 3-person Sulek-Class dilithium-scouting prospector starship was named after the infamous con-man, USS Jefferson Randolph Smith, NCC-29402.[45]

- Tara Kane (2001), presents a fictionalized version of Soapy Smith (and his death) featured in George Markstein's novel.[46]

- American Gods (2002), Smith and his schemes are mentioned repeatedly in the novel by Neil Gaiman.[47]

- Lili Klondike (2008), a book by Mylène Gilbert-Dumas, Smith is the villain.[48]

- The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford (2013), Smith is depicted as a business rival of an antagonist to Robert Ford in the novel by Ron Hansen.[49]

- The Klondike (1996), Smith appears in a Lucky Luke story by Jean Léturgie.[50]

Film

- The Girl Alaska (1919) is believed to be the first portrayal of Soapy Smith. The film was shown in a theater in St. Louis, where Soapy's widow and son lived and caused them to sue the production company.[citation needed]

- Call of the Wild (1935), portrayed by Harry Woods.

- Honky Tonk (1941), portrayed by Clark Gable. Due to legal pressure from Smith's descendants, the name "Soapy Smith" was changed to "Candy Johnson."[citation needed]

- The Great Jesse James Raid (1953), portrayed by Earle Hodgins.

- The Far Country (1955), John McIntire portrays a character loosely based on Smith.

- Klondike Fever (1980), portrayed by Rod Steiger.

- The Call of the Wild (2020), an extra bearing a striking resemblance to Smith can be seen in an Alaskan saloon in a dark suit and wide-brimmed white hat.

Television

- The Alaskans (1959–1960), portrayed by John Dehner.

- Alias Smith and Jones (1971–1972), portrayed by Sam Jaffe in three episodes: "The Great Shell Game" (aired February 18, 1971), "A Fistful of Diamonds" (March 4, 1971), and "Bad Night in Big Butte" (March 2, 1972).

- Klondike (2014), portrayed by Ian Hart. The series depicts Smith operating in Dawson City in 1897 as opposed to Skagway and instead of dying in a shootout, he is stabbed to death by a Tlingit.

- An Klondike (2015–2017), portrayed by Michael Glenn Murphy. Smith's nationality was changed to English in the series, which depicts him as operating in the fictional town of Dominion Creek.

- HBO television series Deadwood (2004–2006): A character known to sell soap with a prize inside, amongst other small cons, like selling fake strands of hair supposedly taken from a decapitated Indian.

Also depicted in a Canadian "Heritage Minute" being refused entry by Sir Sam Steele into the Klondike during the gold rush.

Citations

- ^ a b Smith 2009, p. 26.

- ^ Smith 2009, p. 20.

- ^ Smith 2009, pp. 26–27.

- ^ a b Robertson & Harris 1961.

- ^ Smith 2009, pp. 74–92.

- ^ Smith 2009, p. 197.

- ^ Smith 2009, p. 40.

- ^ Smith 2009, pp. 38–51.

- ^ Smith 2009, p. 45.

- ^ Smith 2009, p. 52.

- ^ Smith 2009, pp. 62–63.

- ^ Smith 2009, p. 124.

- ^ Smith 2009, p. 89.

- ^ Smith 2009, pp. 83–84.

- ^ Smith 2009, pp. 138–139.

- ^ Rocky Mountain News 02/29/1892, p. 6.

- ^ Smith 2009, p. 209.

- ^ Smith 2009, pp. 237–243.

- ^ Smith 2009, p. 245.

- ^ Smith 2009, p. 71.

- ^ The Road, 29 February 1896

- ^ Denver Times, 23 March 1894

- ^ Smith 2009, pp. 294–316.

- ^ Smith 2009, p. 321.

- ^ Smith 2009, pp. 361–363.

- ^ Smith 2009, pp. 450–451.

- ^ Spude 2012, pp. 22–34.

- ^ Smith 2009, p. 442.

- ^ Smith 2009, p. 510.

- ^ Smith 2009, p. 480.

- ^ Collier's Weekly, 11/09/1901

- ^ Smith 2009, p. 482.

- ^ Lyon, Robert, ed. (2010). Jeff. Smiths Parlor Museum: Historic Structure Report : Skagway and White Pass District National Historic Landmark, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, Skagway, Alaska (PDF). Anchorage, Alaska: U.S. Dept. of the Interior, National Park Service, Alaska Regional Office. Retrieved 8 July 2018.

- ^ Pierre Berton, The Klondike Fever, Knopf, 1967, p. 149

- ^ Smith 2009, p. 468.

- ^ Spude 2012, pp. 35–55.

- ^ Smith 2009, pp. 487–490.

- ^ The Skaguay News, 15 July 1898

- ^ Archives of Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, RG 18-A, Samuel B. Steele Collection, Vol. 154, File 447-98, Letter dated July 11, 1898.

- ^ Black, Jack (1926). You Can't Win. AK Press/Nabat. ISBN 9781902593029.

- ^ Blankenship, William-D (1977). Yukon Gold. E. P. Dutton. ISBN 9780525239451.

- ^ Dailey, Janet (1987). The Great Alone. Pocket Books. ISBN 9780671875046.

- ^ "The Yukon Trail (Video Game)". TV Tropes. Retrieved 2023-07-11.

- ^ Bryan, Peter Cullen (2021-05-17). Creation, Translation, and Adaptation in Donald Duck Comics: The Dream of Three Lifetimes. Springer Nature. ISBN 978-3-030-73636-1.

- ^ Ford, John (2000). How Much for Just the Planet. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9780743419871.

- ^ Markstein, George (2001). Tara Kane. House of Stratus. ISBN 978-0-7551-0295-2.

- ^ Gaiman, Neil (2002). American Gods. Harper Collins. ISBN 9780380789030.

- ^ Gilbert-Dumas, Mylène (2008). Lili Klondike. ISBN 9782890059887.

- ^ Hansen, Ron (2013-05-28). The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford. Open Road Media. ISBN 978-1-4804-2388-6.

- ^ Léturgie, Jean (2020). The Klondike. CineBook. ISBN 9781849184960.

General and cited references

- Robertson, Frank C.; Harris, Beth Kay (1961). Soapy Smith: King of the Frontier Con Men. New York City: Hastings House. ISBN 978-0-8038-6661-4.

- Smith, Jeff (2009). Alias Soapy Smith: The Life and Death of a Scoundrel. Klondike Research. ISBN 978-0-9819743-0-9.

- Spude, Catherine Holder (2012). "That Fiend in Hell": Soapy Smith in Legend. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-4280-7.

Further reading

- Collier, William R. and Edwin V. Westrate, The Reign of Soapy Smith: Monarch of Misrule, New York: Doubleday, Doran, 1935.

- Pullen, Harriet S., Soapy Smith Bandit of Skagway: How He Lived; How He Died, Stroller's Weekly Print, undated (the early 1900s).

- Shea & Patten, The Soapy Smith Tragedy, The Daily Alaskan Print, 1907.

- Warman, Cy (September 4, 1898). "The Passing of "Soapy" Smith: Reminiscences of the Notorious Klondike Gambler, Confidence Man and Politician Who Met His Death While Trying to Clean Out a Vigilance Committee That Proved Too Strong for Him". San Francisco Call. Vol. 84, no. 96. Retrieved May 17, 2012.