Secret ballot

| Part of the Politics series |

| Voting |

|---|

|

|

The secret ballot, also known as the Australian ballot,[1] is a voting method in which a voter's identity in an election or a referendum is anonymous. This forestalls attempts to influence the voter by intimidation, blackmailing, and potential vote buying. This system is one means of achieving the goal of political privacy.

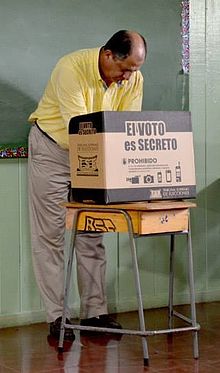

Secret ballots are used in conjunction with various voting systems. The most basic form of a secret ballot utilizes paper ballots upon which each voter marks their choices. Without revealing the votes, the voter folds the ballot paper in half and places it in a sealed box. This box is later emptied for counting. An aspect of secret voting is the provision of a voting booth to enable the voter to write on the ballot paper without others being able to see what is being written. Today, printed ballot papers are usually provided, with the names of the candidates or questions and respective check boxes. Provisions are made at the polling place for the voters to record their preferences in secret, and the ballots are designed to eliminate bias and prevent anyone from linking voters to the ballot.

A privacy problem arises with moves to improve the efficiency of voting by the introduction of postal voting and remote electronic voting. Some countries permit proxy voting, but some argue this is inconsistent with voting privacy. The popularity of the ballot selfie has challenged the secrecy of in-person voting.

In systems of direct democracy, such as the Swiss Landsgemeinde, voting is typically conducted publicly to ensure all citizens can observe the outcome.

Secret vs. public methods

The secret ballot became commonplace for individual citizens in democracies worldwide by the late 20th century.

Votes taken by elected officials are typically public, so citizens can judge officials' and former officials' voting records in future elections. This may be done with a physical or electronic in-person system or through a roll call vote. Some faster legislative voting methods do not record who voted in which way, though witnesses in the legislative chambers may still notice a given legislator's vote. These include voice votes where the volume of shouting for or against is taken as a measure of numerical support and counting of raised hands. In some cases, a secret ballot is used to allow representatives to choose party leadership without fear of retaliation against those voting for losing candidates. The parliamentary tactics of forcing or avoiding a roll call vote can be used to discourage or encourage representatives to vote in a manner that is politically unpopular among constituents (for example, if a policy considered to be in the public interest is difficult to explain or unpopular but without a better alternative, or to hide pandering to a special interest) or to create or prevent fodder for political campaigns.

Public methods of citizen voting have included:

- Oral proclamation, where votes are shouted out one at a time, usually at an assembly[2]

- Going to a particular area at an assembly, such as a town meeting or the Iowa caucus. This is the origin of the term poll for an election, originally meaning "top of the head", which is what was being counted at these assemblies.[2]

- Small balls or other objects, such as corn, pebbles, beans, bullets, colored marbles, or cards. This is the origin of the term ballot, originally meaning "small ball".[2]

- Raising of hands at an assembly

- Cutting a brightly colored ballot (with the color corresponding to the party of choice) out of a newspaper and bringing it to a polling place[2]

- An open ballot system

Private methods of citizen voting have included:

- Writing the name of the preferred candidate or outcome on a piece of paper and putting it in a container (which excludes illiterate voters)[2]

- Marking a government-printed ballot (which may exclude illiterate voters if they only include words and cannot get assistance,[2] but some ballots include colors, symbols, or pictures to avoid this)

History

Ancient

In ancient Greece, secret ballots were used in several situations like ostracism[3] and also to remain hidden from people seeking favors.[4] In early 5th century BC the secrecy of ballot at ecclesia was not the primary concern, but more of a consequence of using ballots to count the votes accurately.[5] Secret ballot was introduced into public life of Athens during second half of the fifth century.[4]

In ancient Rome, the Tabellariae Leges (English: Ballot Laws) were four laws that implemented secret ballots for votes cast regarding each of the major elected assemblies of the Roman Republic. Three of the four laws were put in place in relatively quick succession, with one each in the years 139 BC, 137 BC, and 131 BC, applying respectively to the elections of magistrates, jury deliberations excepting charges of treason as well as the passage of laws. The final of the four laws was implemented more than two decades later in 107 BC and served solely to expand the law passed in 137 BC to require secret ballots for all jury deliberations, including treason.[6]

Before these ballot laws, one was required to verbally provide their vote to an individual responsible for tallying the votes, effectively publicly making every voter's vote known. Mandating secret ballots had the effect of reducing the influence of the Roman aristocracy, who were capable of influencing elections through a combination of bribes and threats. Secret balloting helps assuage both of those concerns, as not only are one's peers unable to determine which way you voted, there is additionally no proof that could be produced that you did vote certain way, perhaps contravening directions .[6]

France

Article 31 of the Constitution of the Year III of the Revolution (1795)[7] states that "All elections are to be held by secret ballot". The same goes with the constitution of 1848:[8] voters could hand-write the name of their preferred candidate on their ballot at home (the only condition was to write on white paper[9]) or receive one distributed on the street.[10] The ballot was folded in order to prevent other people from reading its contents.[10]

Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte attempted to abolish the secret ballot for the 1851 plebiscite with an electoral decree requesting electors to write down "yes" or "no" (in French: "oui" or "non") under the eyes of everyone. But he faced strong opposition and finally changed his mind, allowing the secret ballot to occur.[11]

According to the official website of the Assemblée nationale (the lower house of the French parliament), the voting booth was permanently adopted only in 1913.[12]

United Kingdom

The demand for a secret ballot was one of the six points of Chartism.[13] The British parliament of the time refused even to consider the Chartist demands. Still, Lord Macaulay, in an 1842 speech, while rejecting Chartism's six points as a whole, admitted that the secret ballot was one of the two points he could support.

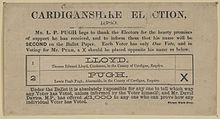

The London School Board election of 1870 was Britain's first large-scale election by secret ballot.

After several failed attempts (several of them spearheaded by George Grote[14]), the secret ballot was eventually extended generally in the Ballot Act 1872, substantially reducing the cost of campaigning (as treating was no longer realistically possible) and was first used on 15 August 1872 to re-elect Hugh Childers as MP for Pontefract in a ministerial by-election following his appointment as Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster. The original ballot box, sealed in wax with a licorice stamp, is held at Pontefract museum.[15]

However, the UK uses numbered ballots to allow courts to intervene, under rare circumstances, to identify which candidate voters voted for.

Australia and New Zealand

In Australia, secret balloting appears to have been first implemented in Tasmania on 7 February 1856.

Until the original Tasmanian Electoral Act 1856 was "re-discovered" recently, credit for the first implementation of the secret ballot often went to Victoria, where the former mayor of Melbourne William Nicholson pioneered it,[16] and simultaneously South Australia.[17] Victoria enacted legislation for secret ballots on 19 March 1856,[18] and South Australian Electoral Commissioner William Boothby generally gets credit for creating the system finally enacted into law in South Australia on 2 April of that same year (a fortnight later). The other British colonies in Australia followed: New South Wales (1858), Queensland (1859), and Western Australia (1877).

State electoral laws, including the secret ballot, applied for the first election of the Australian parliament in 1901, and the system has continued to be a feature of federal elections and referendums. The Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 does not explicitly set out the secret ballot, but a reading of sections 206, 207, 325, and 327 of the Act would imply its assumption. Sections 323 and 226(4), however, apply the principle of a secret ballot to polling staff and would also support the assumption.

New Zealand implemented secret voting in 1870.[citation needed]

United States

Before the final years of the 19th century, partisan newspapers printed filled-out ballots, which party workers distributed on election day so voters could drop them directly into the boxes. Individual states moved to secret ballots soon after the presidential election of 1884, finishing with Kentucky in 1891 when it quit using an oral ballot.[19][page needed]

Initially, however, a state's new ballot did not necessarily have all four components of an "Australian ballot":[20]

- an official ballot being printed at public expense,

- on which the names of the nominated candidates of all parties and all proposals appear,

- being distributed only at the polling place and

- being marked in secret.

After ballots are cast and no longer identifiable to the voter, several states make the ballots and copies of them available to the public so the public can check counts and do other research with the anonymous ballots.[21][22]

Louisville, Kentucky, was the first city in the United States to adopt the Australian ballot. It was drafted by Lewis Naphtali Dembitz, the uncle of and inspiration for future Supreme Court associate justice Louis Brandeis. Massachusetts adopted the first state-wide Australian ballot, written by reformer Richard Henry Dana III, in 1888. Consequently, it is also known as the "Massachusetts ballot". Seven states did not have government-printed ballots until the 20th century. Georgia started using them in 1922.[23] When South Carolina followed suit in 1950, this completed the nationwide switch to Australian ballots. The 20th century also brought the first criminal prohibitions against buying votes in 1925.[24]

While U.S. elections are now held primarily by secret ballot, there are a few exceptions:

- North Carolina has a confidential but not secret ballot for early in-person voting (one-stop) and absentee-by-mail voting. General Statute § 163-227.5 states that the "ballot shall have a ballot number on it in accordance with G.S. 163-230.1(a2), or shall have an equivalent identifier to allow for retrievability." If a voter casts an absentee ballot or votes at a one-stop site (early voting) or absentee-by-mail, but it is discovered that the voter was ineligible (ex., died between casting ballot and election day), the ballot would be retrieved using a unique number written at the top of the ballot. Each county Election Director maintains a database with the names of each voter and associated retrievable ballot numbers.

- Mail-in ballots do not meet the definition of Australian ballots, as they are distributed to voters' homes, and there is no guarantee that they are marked secretly. They may be used as absentee ballots, and Colorado, Oregon, and Washington conduct all elections by mail.[25]

- In some U.S. states, a political party nominating caucus requires an open ballot system. This includes, most notably, the leadoff Presidential nominating state of Iowa.

- The Constitution of West Virginia specifies that voters may choose to cast an open ballot, though they must also have the option to cast a secret ballot.[26]

International law

The right to hold elections by secret ballot is included in numerous treaties and international agreements that obligate their signatory states:

- Article 21.3 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights states, "The will of the people...shall be expressed in periodic and genuine elections which...shall be held by secret vote or by equivalent free voting procedures."[27]

- Article 23 of the American Convention on Human Rights (the Pact of San Jose, Costa Rica) grants to every citizen of member states of the Organization of American States the right and opportunity "to vote and to be elected in genuine periodic elections, which shall be by universal and equal suffrage and by secret ballot that guarantees the free expression of the will of the voters".[28]

- Paragraph 7.4 of the Document of the Copenhagen Meeting of the Conference on the Human Dimension of the CSCE obligates the member states of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe to "ensure that votes are cast by secret ballot or by equivalent free voting procedure, and that they are counted and reported honestly with the official results made public."[29]

- Article 5 of the Convention on the Standards of Democratic Elections, Electoral Rights and Freedoms in the Member States of the Commonwealth of Independent States obligates electoral bodies not to perform "any action violating the principle of voter's secret will expression."[30]

- Article 29 of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities requires that all Contracting States protect "the right of persons with disabilities to vote by secret ballot in elections and public referendums"

Disabled people

Ballot design and polling place architecture often deny the disabled the possibility to cast a vote secretly. In many democracies disabled persons may vote by appointing another person who is allowed to join them in the voting booth and fill the ballot in their name.[31] This does not assure secrecy of the ballot.

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, which entered into force in 2008, ensures a secret ballot for disabled voters. Article 29 of the Convention requires that all Contracting States protect "the right of the person with disabilities to vote by secret ballot in elections and public referendums". According to this provision, each Contracting State should provide voting equipment enabling disabled voters to vote independently and secretly. Some democracies, e.g. the United States, the Netherlands, Slovenia, Albania or India allow disabled voters to use electronic voting machines. In others, among them Azerbaijan, Canada, Ghana, the United Kingdom, and most African and Asian countries, visually impaired voters can use ballots in Braille or paper ballot templates. Article 29 also requires that Contracting States ensure "that voting procedures, facilities and materials are appropriate, accessible and easy to understand and use." In some democracies, e.g., the United Kingdom, Sweden and the United States, all the polling places already are fully accessible for disabled voters.[citation needed]

Secrecy exceptions

The United Kingdom secret ballot arrangements are sometimes criticized because linking a ballot paper to the voter who cast it is possible. Each ballot paper is individually numbered, and each elector has a number. When an elector is given a ballot paper, their number is noted down on the counterfoil of the ballot paper (which also carries the ballot paper number). This means, of course, that the secrecy of the ballot is not guaranteed if anyone can gain access to the counterfoils, which are locked away securely before the ballot boxes are opened at the count. Polling station officials colluding with election scrutineers may, therefore, determine how individual electors have voted.[speculation?]

This measure is thought to be justified as a security arrangement so that false ballot papers could be identified if there was an allegation of fraud. The process of matching ballot papers to voters is formally permissible only if an Election Court requires it; the Election Court has rarely made such an order since the secret ballot was introduced in 1872. One example was in a close local election contest in Richmond-upon-Thames in the late 1970s with three disputed ballots and a declared majority of two votes. Reportedly, prisoners in a UK prison were observed identifying voters' ballot votes on a list in 2008.[32] The legal authority for this system is set out in the Parliamentary Elections Rules in Schedule 1 of the Representation of the People Act 1983.[33]

Most states guarantee a secret ballot in the United States. But some states, including Indiana and North Carolina, require the ability to link some ballots to voters. This may, for example, be used with absentee voting to retain the ability to cancel a vote if the voter dies before election day.[34][35] Sometimes the number on the ballot is printed on a perforated stub which is torn off and placed on a ring (like a shower curtain ring) before the ballot is cast into the ballot box. The stubs prove that an elector has voted and ensure they can only vote once, but the ballots are both secret and anonymous. At the end of voting day, the number of ballots inside the box should match the number of stubs on the ring, certifying that a registered elector cast every ballot and that none of them were lost or fabricated. Sometimes, the ballots themselves are numbered, making the vote trackable. In 2012 in Colorado, this procedure was ruled legal by Federal District Judge Christine Arguello, who determined that the U.S. Constitution does not grant a right to a secret ballot.[36]

Chronology of introduction

| Date | Country | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1831 | France | Systems before 1856 (including those in France, the Netherlands, and Colombia) "merely required ballots to be marked in polling booths and deposited into ballot boxes, which permitted non-uniform ballots, including ballots of different colours and sizes, that could be easily identified as party tickets."[37] |

| 1856 (February 7) | Australia (Tasmania) | The other Australian colonies of Victoria (March 19, 1856), South Australia (April 2, 1856), New South Wales (1858), Queensland (1859), and Western Australia (1877) followed. |

| 1866 | Sweden | Voters previously chose a party-specific ballot in the open, which had been criticised for limiting the secrecy. However, the ballots are now placed behind a privacy screen, so the secrecy remains.[38] European Commission for democracy through law (Venice Commission) "Voters are entitled to [secrecy of ballot], but must also respect it themselves, and non-compliance must be punished by disqualifying any ballot paper whose content has been disclosed [...] Violation of the secrecy of the ballot must be punished, just like violations of other aspects of voter freedom." (Code of good practice in electoral matters, art. 52, 55) |

| 1867 | Germany | August 1867 North German federal election |

| 1872 | United Kingdom | Ballot Act 1872 |

| 1877 | Belgium | The Act of 9 July 1877 or "Malou Act", based on the British Ballot Act 1872 |

| 1891 | United States of America | Individual states adopted secret ballots between 1884 and 1891. (Massachusetts was the first to meet all of the Australian ballot requirements in 1888. South Carolina was the last, in 1950.) |

| 1901 | Denmark | In connection with The Shift of Government (Danish: Systemskiftet)[39] |

| 1903 | Iceland | Originally passed by the Icelandic parliament in 1902, but the legislation was rejected by King Christian IX for technical reasons unrelated to ballot secrecy.[40] Passed into law 1903.[41] |

| 1912 | Argentina | Sáenz Peña Law |

| 1939 | Hungary | The secret ballot system was already applied at the 1920 elections, but in 1922, the government reinstated open voting in the countryside. Between 1922 and 1939, only the voters in the capital (Budapest) and larger cities could vote with secret ballot. The electoral law passed in 1938 introduced the nationwide secret ballot system again. |

See also

References

- ^ "Australian ballot | politics". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 2019-08-11. Retrieved 2018-11-09.

- ^ a b c d e f "How We Vote – Throughline podcast". NPR. 22 Oct 2020. Archived from the original on 12 February 2021. Retrieved 7 February 2021.

- ^ Murray, Oswyn (1993). Early Greece (2nd ed.). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674221321.

- ^ a b Boegehold, Alan L. (October 1963). "Toward a Study of Athenian Voting Procedure". Hesperia. 32 (4): 366–372. doi:10.2307/147360. JSTOR 147360.

- ^ Hansen, Mogens Herman (1983). The Athenian Ecclesia : a collection of articles 1976–1983. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press. p. 111. ISBN 9788788073522.

- ^ a b Yakobson, Alexander (1995). "Secret Ballot and Its Effects in the Late Roman Republic". Hermes. 123 (4): 426–442. JSTOR 4477105. Archived from the original on May 3, 2022. Retrieved May 3, 2022.

- ^

Full text of the Constitution of the Year III on Wikisource (in French)

Full text of the Constitution of the Year III on Wikisource (in French)

- ^ Article 24. — Le suffrage est direct et universel. Le scrutin est secret. s:fr:Constitution du 4 novembre 1848

- ^ Pour être recevable, chaque vote doit être inscrit sur un papier blanc : fr:Élection présidentielle française de 1848

- ^ a b See the picture captioned Distribution des bulletins d'élections dans les rues. L'Illustration du 23 septembre 1848 on Assemblée Nationale website Archived 2010-08-20 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Karl Marx The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Napoleon : "For the bourgeois and the shopkeeper had learned that in one of his decrees of December 2 Bonaparte had abolished the secret ballot and had ordered them to put a "yes" or "no" after their names on the official registers. The resistance of December 4 intimidated Bonaparte. During the night he had placards posted on all the street corners of Paris announcing the restoration of the secret ballot." Full text (chapter VII) Archived 2010-10-18 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Nationale, Assemblée. "Le suffrage universel – Histoire". www.assemblee-nationale.fr. Archived from the original on 24 May 2014. Retrieved 24 March 2018.

- ^ In the words of the petition that was published in 1838:

- ^ Kinzer, Bruce (2004), "George Grote, the Philosophical Radical and Politician", Brill's Companion to George Grote and the Classical Tradition, London: Brill, pp. 16–45

- ^ "BBC – A History of the World – Object : Pontefract's secret ballot box, 1872". www.bbc.co.uk. Archived from the original on 16 December 2019. Retrieved 24 March 2018.

- ^ Blainey, G 2016, "The story of Australia's people: the rise and rise of a new Australia", Viking, Penguin Random House, Ringwood, Victoria, Australia, p.18.

- ^ Terry Newman, "Tasmania and the Secret Ballot" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-05-20. Retrieved 2015-05-19. (144 KiB) (2003), 49(1) Aust J Pol & Hist 93, accessed May 20, 2015

- ^ "Documenting Democracy". foundingdocs.gov.au. Archived from the original on 3 April 2018. Retrieved 24 March 2018.

- ^ Eldon Cobb Evans, A History of the Australian Ballot System in the United States# (1917) online.

- ^ Webster's Seventh New Collegiate Dictionary. Springfield, Massachusetts: G&C Merriam Company. 1967. p. 59.

- ^ "I. Election Records Archives". Archived from the original on May 25, 2022. Retrieved May 3, 2022.

- ^ "Reporters Committee Election Legal Guide | Updated 2020". www.rcfp.org. Archived from the original on April 27, 2022. Retrieved May 3, 2022.

- ^ See 1922 Georgia session laws, chapter 530, p. 100.

- ^ "18 U.S. Code § 597 – Expenditures to influence voting". LII / Legal Information Institute. Archived from the original on 16 February 2018. Retrieved 24 March 2018.

- ^ Washington Secretary of State. "Vote by Mail in Washington State". State of Washington. Archived from the original on 27 April 2014. Retrieved 27 April 2014.

- ^ See W. Va. Const. Art. IV, §2, "In all elections by the people, the mode of voting shall be by ballot; but the voter shall be left free to vote by either open, sealed or secret ballot, as he may elect".

- ^ "Universal Declaration of Human Rights". www.un.org. Retrieved 24 March 2018.

- ^ American Convention on Human Rights, "Pact of San Jose", Costa Rica Archived 2015-02-11 at the Wayback Machine, Organization of American States, Nov. 22, 1969.

- ^ Document of the Copenhagen Meeting of the Conference on the Human Dimension of the CSCE Archived 2015-02-11 at the Wayback Machine, Copenhagen, June 29, 1990.

- ^ Convention on the Standards of Democratic Elections, Electoral Rights and Freedoms in the Member States of the Commonwealth of Independent States Archived 2015-02-11 at the Wayback Machine, Oct. 7, 2002, Chisinau. Unofficial English translation provided by the European Commission for Democracy through Law (Venice Commission), Jan. 22, 2007.

- ^ Mercurio, Bryan (2003). "Discrimination in Electoral Law". Alternative Law Journal. 28 (6): 272–276. doi:10.1177/1037969X0302800603. S2CID 147550553. Archived from the original on 2018-10-11. Retrieved 2018-10-10.

- ^ "What happens to the voting slips used in British elections after they have been counted? | Notes and Queries | guardian.co.uk". www.theguardian.com. Archived from the original on 2017-01-16. Retrieved 2016-12-16.

- ^ "Factsheet: Ballot secrecy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-12-09. (48 KiB) (2006), Electoral Commission of the United Kingdom

- ^ "2020 Indiana Election Administrator's Manual" (PDF). in.gov. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-01-19. Retrieved 2020-03-02.

- ^ Wilkie, Jordan (2019-07-11). "'A risk to democracy': North Carolina law may be violating secrecy of the ballot". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 2020-03-02. Retrieved 2020-03-02.

- ^ "Federal judge says no constitutional right to secret ballot in Boulder case". 21 September 2012. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 24 March 2018.

- ^ Ben Smyth, A foundation for secret, verifiable elections, IACR Cryptology ePrint Archive, 2018

- ^ "Rösta på valdagen". val.se (in Swedish). Archived from the original on 2022-12-05. Retrieved 2022-12-05.

- ^ Elklit, Jørgen (1988). Fra åben til hemmelig afstemning. Århus, Denmark: Politica. pp. 299 ff.

- ^ Stjórnartíðindi [Legal Gazette] (in Icelandic). Icelandic Government. 1902. pp. 273–275.

- ^ Alþingistíðindi [Parliamentary Gazette] (in Icelandic). Alþingi. 1903. pp. 120–133.

External links

![]() Works related to A History of the Australian Ballot System in the United States at Wikisource

Works related to A History of the Australian Ballot System in the United States at Wikisource

- The Ballot Bill [UK] The Annual Register, 1872, p. 61.