Second Triumvirate

|

|---|

| Periods |

|

| Constitution |

| Political institutions |

| Assemblies |

| Ordinary magistrates |

| Extraordinary magistrates |

| Public law |

| Senatus consultum ultimum |

| Titles and honours |

|

| Part of a series on |

| Ancient Rome and the fall of the Republic |

|---|

|

People

Events

Places |

The Second Triumvirate was an extraordinary commission and magistracy created at the end of the Roman republic for Mark Antony, Lepidus, and Octavian to give them practically absolute power. It was formally constituted by law on[1] 27 November 43 BC with a term of five years; it was renewed in 37 BC for another five years before expiring in 32 BC. Constituted by the lex Titia, the triumvirs were given broad powers to make or repeal legislation, issue judicial punishments without due process or right of appeal, and appoint all other magistrates. The triumvirs also split the Roman world into three sets of provinces.

The triumvirate, formed in the aftermath of a conflict between Antony and the senate, emerged as a force to reassert Caesarian control over the western provinces and wage war on the liberatores led by the men who assassinated Julius Caesar. After proscriptions, purging the senatorial and equestrian orders, and a brutal civil war, the liberatores were defeated at the Battle of Philippi.[2] After Philippi, Antony and Octavian took the east and west, respectively, with Lepidus confined to Africa. The last remaining opposition to the Triumvirs came from Sextus Pompey, a son of Pompey the Great, who controlled Sicily, Corsica and Sardinia.

Octavian and Antony were pushed to cooperation, in part by their soldiers, and the triumvirs had their legal arrangement renewed for another five years in 37 BC. Eventually, after Antony's defeat in Parthia and Octavian's victory over Sextus Pompey, Octavian forced Lepidus from the triumvirate in 36 BC. Relations between the two remaining triumvirs broke down in the late 30s BC before they fought a final war, from which Octavian emerged the victor.

Name

The name "Second Triumvirate" is a modern misnomer derived from the branding of the political alliance between Pompey, Crassus, and Caesar (created c. 59 BC) as the "First" Triumvirate. This nomenclature was unknown during and before the Renaissance and was first attested in the late 17th century, coming into widespread use only in the following century.[3] Recent books have started to avoid the traditional nomenclature of "First" and "Second" Triumvirates.[4] The Oxford Classical Dictionary, for example, warns "'First' and 'Second Triumvirate' are modern and misleading terms".[1]

Triumviral period

Following the assassination of Julius Caesar on 15 March 44 BC, there was initially a settlement reached between the perpetrators, who styled themselves liberatores, and remaining Caesarian supporters. This settlement included an amnesty for the tyrannicides, confirmation of Caesar's official actions, and abolition of the dictatorship.[5] By late spring 44 BC, the provinces assigned by Caesar before his death – many to his later killers – were largely confirmed.[6]

Mark Antony was one of the consuls for 44 BC and on 2 June 44 BC, was able to push through illegal legislation assigning to himself the provinces of Cisalpine and Transalpine Gaul, displacing their existing governors.[7] These governorships secured for Antony a political future where he would be able to intimidate the senate and Italy from across the river Rubicon. Antony also persuaded the senate to disarm Marcus Brutus and Cassius (the two leading tyrannicides) giving them grain supply assignments; both men viewed these assignments as insults, later compounded by their assignment to minor provinces after their praetorships.[8]

Relations between Antony and Caesar's legal heir, Octavian, also started to break down: Octavian was successful in attracting some of Caesar's veterans from Antony's camp, undercutting Antony's military support.[8] Antony also sought later in the year to isolate Cicero politically, as the eloquent ex-consul was prestigious and on friendly terms with large portions of the aristocracy.[9] Octavian, starting a bidding war for extreme Caesarians, broke with Antony and formed for himself a private army. In December 44 BC, Cicero induced the senate to honour Octavian's efforts and to support the existing governors of Cisalpine and Transalpine Gaul in retaining their provinces against Antony.[10] The senate's forces, led by the two consuls and Octavian, put Antony to flight at the Battle of Mutina on 21 April 43 BC.[11][12] After news of the victory, Cicero had the senate declare Antony a public enemy. But with both consuls dead, Octavian moved against the senate – both sides knew they were only using the other – and marched south to secure for himself the consulships opened by their deaths.[13]

Creation, 43 BC

After Octavian and his forces reached Rome on 19 August 43 BC, he secured for himself election to the consulship with his cousin Quintus Pedius. They moved quickly to enact legislation confirming Octavian's adoption as Caesar's heir and establishing courts to condemn Caesar's assassins in absentia.[14][15] They also repealed the declaration of Antony as a public enemy. Octavian then moved north to treat with Antony under Lepidus' protection. With the Caesarian soldiers' urging, Octavian and Antony reconciled; Octavian also would marry Antony's step-daughter Clodia.[14] The three men then established themselves as the triumviri rei publicae constituendae (the latter words indicate a causa or commission for the reconstitution of the republic[16]) for five years. This was confirmed by the lex Titia, proposed by a friendly tribune at their request.[17]

The law was modelled on the lex Valeria in 82 BC which established Sulla's dictatorship.[18] They received power to issue legally binding edicts,[19] were granted imperium maius which permitted them to overrule the ordinary provincial governors and to take credit for their victories,[20][21] and to act sine provocatione (without right of appeal).[22] They also received powers to call the senate and directly appoint magistrates and provincial governors.[23] The legal powers given, exceeding those of the ordinary consuls, were noted on the Capitoline Fasti, which list the triumvirs above the consuls.[24]

Octavian and Antony then prepared to wage war on the liberatores with forty total legions. They also divided the western Roman world:

- Antony would receive Cisalpine and Transalpine Gaul,

- Lepidus would receive Narbonensis and Spain, and

- Octavian (then the junior partner) would receive Africa, Sardinia, and Sicily.[14]

The triumvirs' powers were initially set to lapse on 31 December 38 BC, though the legal powers may have been retained (after their later renewal in 38 BC) all the way until 27 BC when Octavian abdicated his magistracy.[25]

Proscriptions

In desperate need of money, the three men issued a declaration which – according to Appian – declared Caesar's clementia to have been a failure; it was appended with a death list.[26] Some three hundred senators and 2,000 equites were then killed;[27] some victims escaped to Macedonia or Sicily (held by Brutus and Sextus Pompey, respectively) or were able to plead successfully for clemency. Still without sufficient funds, the triumvirs seized eighteen rich Italian towns and redistributed them to their soldiers.[14]

The proscriptions claimed enemies and friends of the triumvirs. Cicero, whom Octavian had held in high esteem, was placed on the death lists along with his brother, nephew, and son; Cicero's activism against Antony in the Philippicae marked him for retribution. The triumvirs themselves traded friends and family to secure the addition of their enemies to the death lists. Persons on the proscription lists had their properties confiscated and sold; freelance assassins, bounty hunters, and informers received cash rewards for aiding in the killings.[28]

Liberators' civil war, 42 BC

Sextus Pompey Brutus & Cassius Rome's client kingdoms Ptolemaic Egypt |

Preparations for war on the tyrannicides started promptly. In Rome, the new year saw Julius Caesar consecrated as a god.[29] With the triumvirs having slaughtered their political enemies in Italy, they moved with some forty legions against Brutus and Cassius in the east: Lepidus remained in Italy – supervised by two pro-Antony governors – while Antony and Octavian moved to cross the Adriatic for Macedonia.[29]

While some eight legions had crossed the Adriatic early in the year, the naval forces of the liberatores and of Sextus Pompey were able to interdict the triumvir's transports. Octavian dispatched Quintus Salvius Salvidienus Rufus against Sextus Pompey's base of operations in Sicily, resulting in a bloody but indecisive battle near Messana.[30] It took until summer for the triumvirs to move all their armies into Macedonia.[31] Through early 42 BC, Brutus and Cassius were active in Asia sacking cities and forcing tribute from the provincials to pay their own soldiers.[32] The liberatores, busy, delayed marching west (perhaps an error in retrospect); they moved to intercept Antony and Octavian only in mid-July.[33]

The triumvirs' advance forces reached Philippi first, but were outmanoeuvred and forced to retreat. Brutus and Cassius, hugely outnumbering the advance force, reached Philippi in early September, forcing the triumvirs' advance forces to retreat. Antony and Octavian arrived some days later. The liberatores first attempted to avoid battle in light of the triumvirs' weak supply situation. But Antony was successful in forcing battle with the construction of earthworks on Cassius' flank.[34]

The liberatores accepted battle, triggering the first battle: Brutus fought Octavian, Cassius fought Antony. Brutus' forces were successful and stormed Octavian's camp and destroying three of Octavian's legions. Cassius' forces, however, were less successful; Antony was able to storm Cassius' camp around the same time. Believing the battle was lost, Cassius committed suicide.[35] In the aftermath, Cassius' forces were amalgamated into Brutus' army.[36]

Three weeks later, on 23 October 42 BC, Brutus offered battle again, fearing desertions and possible cutting of his supply lines.[35] In this second battle, the combined forces of Antony and Octavian defeated Brutus' army. Antony was largely the victor – Octavian apparently spent most of the first battle hiding in a marsh[37] – and had forced the liberatores to battle and defeat twice.[35] In the aftermath, Brutus committed suicide.[38]

Antony turns east

In the aftermath of Philippi, Antony moved to reorganise the wealthy eastern provinces. His provinces and legions were also adduced: retaining Transalpine Gaul, he took Narbonensis from Lepidus, though he gave up Cisalpine Gaul to Italy. Octavian's assignment was less easy: he would have the privilege of settling the veterans of Philippi in Italy and carrying on the war against Sextus Pompey in Sicily. Lepidus, however, not sharing in the glory, gave Spain to Octavian in return for Africa only.[39] This new strategic position placed Antony at the head of an enormous advantage. His position in the east allowed him enormous resources with which he could overwhelm the west as Sulla had. His position in Gaul gave him easy access to Italy, just as Caesar had before his civil war. Moreover, while Antony would be in the east, his trusted lieutenants controlled the Gallic provinces. This strategic position placed him firmly at the head of the triumvirate.[40]

Antony moved first against Parthia, which had aided the liberatores and was harbouring the Pompeian commander Quintus Labienus, (son of Titus Labienus who had served with Caesar during the Gallic wars and fought against him during the civil war).[41] In the preparations for war, however, Antony found most of the east largely sucked dry by the previous armies of Dolabella, Cassius, and Brutus. Antony, however, was gentle with the areas that Brutus and Cassius had pillaged. He also displayed favour for great cultural centres and toured the eastern provinces seeking to buttress popular support.[42]

Moving down the Mediterranean coast, Antony confirmed a number of rulers – in spite of their previous support for the liberatores or for Parthia – in Palestine and called Cleopatra to attend to him in Cilicia.[43] Cleopatra quickly entered into an affair with Antony, which proved useful to her: Antony helped her secure her throne with the death of her sister Arsinoe and against other Ptolemaic claimants. While ancient writers speculated on Antony being manipulated by the Egyptian queen, it is more likely in this period he was merely attempting to strengthen Cleopatra's position in Egypt as part of his policy of favouring strong allied monarchs. Regardless, he left her in the spring of 40 to embark on a campaign against Parthia.[44]

The Parthians, in the winter of 41 BC, knowing that Antony was preparing an offensive, struck first. Invading Asia Minor and Syria under the command of Pacorus and Quintus Labienus in the early spring of 40 BC, the Parthian forces were largely unchallenged: Pacorus moved south for Palestine while Labienus moved west through Cilicia for Ionia.[45] Antony at the time was wholly distracted from the Parthian invasion due to the Perusine War.[46]

Perusine War, 41–40 BC

The veterans' demands for lands in Italy – in the midst of a famine, which itself was exacerbated by Sextus Pompey's naval blockade of Italy, – caused protests and unrest throughout the Italian countryside.[47] Antony's brother, Lucius Antonius, serving as consul for 41 BC, and Antony's wife Fulvia fanned the flames of this unrest to undermine Octavian.[48] They spread propaganda indicting Octavian's regime with stomping on citizen rights and favouring Octavian's veterans over Antony's. Although there was little truth behind these charges, they were largely able to build up support for a militant rising against Octavian.[49]

Antony attempted to remain largely aloof to the goings-on, probably so he could exploit the outcome, but his supporters in Italy were largely uninformed of his intentions and readied for conflict. The consul Lucius, in the summer of 41 BC, occupied Rome with an army; however, he was beaten back by Octavian's forces and besieged in Perusia. Unsure of Antony's intentions, the pro-Antony governors in the two Gauls and in southern Italy stood by. Eventually, Perusia was captured: Octavian let Lucius Antonius and Fulvia go and spared Lucius' soldiers when Octavian's own soldiers interceded; Octavian, however, sacked the town, massacred its councillors, and had it burnt to the ground.[50]

After the death of one of the pro-Antony governors in Gaul in the summer of 40 BC, Octavian occupied the province. He also gained the support of the legions in southern Italy. Antony, concerned, hurried back to Italy from the east that same summer with substantial forces.[51]

Treaties of Brundisium and Misenum, 40–39 BC

As relations deteriorated between Antony and Octavian, Octavian moved to woo Sextus Pompey over to his side. As part of this, he married Scribonia, Sextus' sister-in-law, in the summer of 40 BC. At the same time, however, Sextus was attempting to broker an agreement with Antony; receiving a positive response from Antony, he raided the Italian coast and took Sardinia from Octavian. Another ex-republican naval commander, Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus, was also induced to join Antony's side.[51]

When Antony sailed to Brundisium, Octavian's garrison of five legions refused to admit him. It was then besieged. Octavian's lieutenant Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa arrived with reinforcements but was turned back after some skirmishing. The troops on both sides, however, urged their leaders to come to terms. Octavian and Antony conducted negotiations through intermediaries (the envoys were Gaius Maecenas and Gaius Asinius Pollio, respectively). Negotiations for the treaty completed in September 40 BC:[52]

- Octavian's occupation of Gaul was recognised; he also would be granted Illyricum.

- Antony would be confirmed as master of the east.

- Lepidus retained Africa.

- Antony would lead a military expedition against Parthia to avenge Crassus' defeat at Carrhae.

- Octavian would either reach an agreement with or defeat Sextus Pompey.

- Amnesty would be granted for former republicans.

- Italy would be shared, but Octavian's personal presence on the peninsula made it de facto one of his territories.[52]

The treaty would be sealed by another marriage: Antony would wed Octavian's sister Octavia. The announcement of peace was greatly celebrated by the people of Italy. Both dynasts celebrated ovations when entering Rome in October. But public opinion soured when they also announced new higher taxes amid further disruption of grain ships from Sextus' fleet.[53] While in Rome, they also secured the senate's rubber stamp for a required dispensation for Octavia's marriage (she was not yet out of mourning for her previous husband) and for triumviral political and territorial settlements generally.[54]

The dynasts also negotiated peace with Sextus Pompey at Misenum in the summer of 39 BC: they confirmed him in Corsica, Sardinia, Sicily, and the Peloponnese for five years. They promised him the consulship in 33 BC on expiration of his commands and had him elected augur. In exchange, Sextus would guarantee free passage of Italian grain ships and suppress Mediterranean piracy; his supporters also would receive amnesty and compensation for seized properties; his soldiers received the same retirement benefits as those of the triumvirs and his runaway slaves were granted freedom.[54] The last concessions to Sextus' soldiers and slave forces were especially important for the triumvirs: with the soldiers and slaves' main grievances resolved, Sextus' military power was permanently neutered.[55] After celebrations for this agreement, Antony departed for the east on 2 October 39 BC.[56]

Renewal of the triumvirate

Antony in the east

While Antony was in Italy, his lieutenant Publius Ventidius scored major victories against the Parthian invasion of Asia Minor: he defeated Labienus' forces and presumably had him killed. He also won the Battle of Amanus Pass against Phranipates, the Parthian satrap of Syria, killing the satrap and forcing the Parthians to retreat beyond the Euphrates. All of these victories were won before the autumn of 39 BC.[56]

Antony wintered in Athens and returned eastward in the spring of 38 BC. With the defence of the provinces largely complete, he prioritised reorganisations in the eastern provinces and client states. Among other boundary adjustments, he gave Cleopatra portions of eastern Cilicia and Cyprus with which to harvest timber to build a fleet. He also started to publicly identify with the god Dionysus.[57] But before he moved further east he was drawn back to Brundisium by Octavian to discuss a worsening situation in Italy; when Octavian did not arrive promptly, he issued a public rebuke and sailed east for Syria, where he found Ventidius' victories uninterrupted.[58] Ventidius was relieved of command by Antony and then returned to Rome to celebrate a triumph on 27 November 38 BC before dying shortly thereafter.[59]

Octavian in the west

The agreement between Sextus Pompey and Octavian, without Antony's presence to balance the two, started to break down in autumn 39 BC. That winter, the famine in Italy and pirate raids on grain ships continued. One of Sextus' admirals also defected to Octavian, giving Octavian back the islands of Sardinia and Corsica, along with three legions and sixty ships. Sextus, outraged, declared war.[59]

Two large naval battles were fought in the spring of 38 BC near Cumae and near Messana. Both resulted in victories for Sextus, but he did not exploit his advantage and allowed Octavian to retire to Campania. Antony likely sought to maintain the power balance between both Octavian and Sextus for his own advantage. Octavian now requested some support after these defeats. To preserve the balance of power, Antony prepared to move west and provide support. There also was a rebellion in Gaul, which Agrippa put down by the end of 38 BC. Agrippa, loyal to Octavian and in light of Octavian's inglorious defeat, tactfully went without a triumph.[60]

Treaty of Tarentum

In the spring of 37 BC, Antony sailed for Italy with 300 ships. Denied entrance at Brundisium (the townsfolk suspected an invasion), he docked at Tarentum instead. Octavian travelled there to meet him. Negotiations dragged on until late July or early August. Antony apparently had to be persuaded by his wife Octavia to support Octavian against Sextus.[61]

They agreed to strip Sextus of his augurate and future consulship. Octavian would wait a year to attack Sextus and would receive 120 ships from Antony in exchange for 20,000 men and 1,000 elite troops.[62] The triumvirate also had uncomfortably expired at the end of 38 BC. Normal republican practice had magistrates abdicate their offices at the close of their terms; the triumvirs' terms had ended, but they had not abdicated. Nor were any successors appointed. Regardless, the legal position of the triumvirs was of little practical relevance. Making a show of constitutionalism, the triumvirate was then renewed by law for another five years, to expire on the last day of 33 BC.[63]

Parthia and Sicily, 36 BC

Preparations for war continued apace. Agrippa, serving as consul in 37 BC, built a large harbour (the portus Julius) to train and supply troops against Sextus in Sicily.[64] In the east, Roman client Herod retook most of Judaea; even better for the Romans, the Parthian threat disappeared amid a dynastic struggle when Orodes II abdicated in favour of his chosen successor Phraates IV, who promptly murdered his father, all of his brothers, and his own son, precipitating a revolt.[65]

Amid a general reorganisation of the east which again strengthened client kingdoms – among a number of changes, Cleopatra received Crete and Cyrene, – Antony fathered a son with Cleopatra and publicly acknowledged his paternity of two twins born in 40 BC. This may have been related to strengthening Antony and Cleopatra's positions in Egypt and building popular support there; even if so, the relationship was unpopular in Italy and Antony should have known this.[66]

Parthian campaign

Antony demanded the return of Crassus' eagles from Phraates; Phraates, needing to ensure his own position, refused.[67] Antony struck north towards Armenia, where he was joined by detachments from allied kings and a Roman governor. With sixteen legions and many auxiliaries, he drove south into Persia.[68] Moving quickly without his siege engines, he arrived to Phraata, the Parthian capital, but then discovered that his slow-moving siege engines had been intercepted and destroyed. He was then abandoned by Artavasdes, the Armenian king; Antony, while successful in some defences, was unable to effectively counter the swift Parthian cavalry.[69]

Abandoning the siege, he was forced into a difficult retreat with few supplies and harried by Parthian archers. Over 27 days, the army returned after a famous display of resilience and valour, to Armenia. Reaching an agreement with Artavasdes, Antony continued to retreat through the winter until he reached Cappadocia.[69] In total, he lost around a third of his entire army.[70]

The failure of the Parthian campaign fatally damaged Antony's military prestige and power. If it had been successful, it would clearly placed him above Octavian; but after its failure, Antony's fortunes turned for the worse.[70]

Sicily

Agrippa prepared exhaustively for Octavian's campaign against Sicily.[70] Octavian also was able to secure support from Lepidus in Africa, who possibly had plans of his own. In July 36 BC, Octavian and Lepidus launched a three-pronged attack on Sicily with Octavian's forces landing in the north and east while Lepidus landed in the south.[70]

Initially, Octavian's naval forces were beset by storms. Lepidus' forces, however, successfully effected a landing in his theatre and placed one of Sextus' lieutenants under siege in Lilybaeum. In the north and east, there were naval battles: Octavian was personally defeated off Tauromenium while Agrippa was victorious off Mylae. Even so, Sextus' forces were stretched thin and Octavian was able to effect landings of 21 legions onto the island. A decisive naval battle ended the campaign, with Agrippa defeating Sextus near Naulochus on 3 September 36 BC. Sextus, able to muster only 17 ships, fled for Antony in the east.[71]

Lepidus, buoyed by victory, attempted to suborn Octavian's troops. After accepting the surrender of Sextus Pompey's legions, he attempted to negotiate with Octavian to exchange Sicily and Africa for his old provinces of Narbonensis and Spain. Octavian, walking into Lepidus' camp almost unaccompanied, secured the loyalty of the soldiers; defeated, Lepidus was then stripped of membership in the triumvirate and his provincial commands. Kept in his property, life, and the title of pontifex maximus, Lepidus was forced into exile and retirement.[72]

Breakdown

With the three reduced to two, Octavian started to prepare for a showdown against Antony. He furthered his attempts to link Antony with Cleopatra and drilled his troops in Illyricum near the dividing line of the provinces. Antony, however, was slow to respond and was focused on the far east against Armenia.[73] In the interim, Sextus arrived in Antony's provinces, where he was caught and executed, though Antony erected some cover of plausible deniability for the actions.[74]

Octavian's troops, believing Octavian's propaganda about having brought to an end the civil wars and restoring peace, started to demand demobilisation. While some of the longest-serving were released, Octavian was keenly aware of his need to keep his men mobilised. To that end, he offered some donatives and a ploy about spoils in Illyricum.[75] He also offered an embassy led by Octavia to transfer to Antony about half of his lent ships and 2, 000 elite men – nowhere near the 20, 000 promised at Tarentum – which had the effect of forcing Antony to choose between accepting Octavian's so-called repayment or insulting his wife in the eyes of the Italians. Antony accepted his wife's troops but bade her to winter in Athens while he went back to Alexandria to stay with Cleopatra.[76]

Propaganda war, 34 BC

Antony, through treacherous means, tricked the Armenian king Artavasdes into a meeting in 34 BC. Capturing the Armenian king, he occupied his country and then paraded him in a Dionysiac procession in Alexandria. Octavian's propaganda seized on the procession as a sacrilege and betrayal of Rome's gods.[77] Antony also engaged on an unwise ceremony, the "donations of Alexandria", where he crowned his children with Cleopatra as oriental monarchs.[78] These antics went down very poorly in Rome. In a political climate which blamed the civil wars on a collapse of public morality, Octavian was able to link Antony with oriental immorality under Cleopatra's influence.[79]

Antony and his supporters, of course, responded: they alleged Octavian to be a coward; they objected to Octavian's shabby treatment of Lepidus; they accused Octavian of monopolising all the land in Italy for his own veterans; they also made allegations that Octavian was stealing ex-consuls' wives and prostituting his daughter Julia to foreign kings.[80]

While the propaganda war was raging, Octavian campaigned in Illyricum; he was successful at defeating, with overwhelming force, a number of barbarian tribes. Able to keep his soldiers in arms and build their experience, he celebrated with friendly generals a large number of triumphs; those triumphs also financed, from the spoils, building and renovation projects in Rome. Octavian and Antony competed on building new public works in the city. Octavian's ally Agrippa also engaged in renovations of the sewers and aqueducts; and during a term as aedile in 33 BC, sponsored spectacular games and public donations.[81]

End of the triumvirate, 32–30 BC

The triumvirate's legal term expired on 31 December 33 BC (Octavian's holding of his triumviral legal powers may have continued to 27 BC).[82] In the new year, Octavian used force to drive the potentially resurgent consuls from Rome after one of the consuls started to publicly attack him.[83] The consuls fled to the east and Antony with several hundred senators, which Antony organised into a "counter-senate".[84]

Antony started to move his massive army, of some 100,000 men and 800 ships, west towards Greece. His men debated whether or not they should permit Cleopatra to stay with them: the main argument to remove her was that her presence would further Octavian's propaganda depicting a war on the east;[85] however, removing her would also demoralise some of their own forces, who were fighting for their queen against Rome rather than for Antony, a Roman general. Arriving in Athens, Antony divorced Octavia; the choice of removing his Roman wife to stay with his Egyptian mistress alienated Italian public opinion.[86]

Lucius Munatius Plancus then fled Antony's camp for Octavian's. Upon his arrival, he recommend that Octavian open Antony's will, legally sealed with the Vestal Virgins. Opening it, Octavian allegedly found that Antony planned to be buried in Alexandria, would recognise Caesarion as Caesar's son, and give large portions of Roman lands to his children with Cleopatra. It is likely that Octavian may have invented provisions: the Vestals in Rome would not have seen the sealed will; some provisions may have been alleged which Antony would find uncomfortable to deny (losing eastern support) or admit (losing western support).[87]

Antony's forces in Greece provoked panic in Italy; Octavian, no longer calling himself triumvir (but retaining his provincial commands) organised defence of the peninsula. He organised a civil oath to his personal leadership, unprecedented in republican history. Declaring war on Cleopatra, Octavian also had the republic strip Antony of his legal position.[88]

Early in the campaigning season of 31 BC, Agrippa launched a series of surprise attacks on the western Greek harbours under Antony's control. Octavian moved quickly to take beachheads on the Greek mainland near Corcyra.[89] After cutting off Antony's supplies and escape by land, Antony and Cleopatra engaged in a sea battle, attempting to break out with his remaining fleet. They fought Octavian on 2 September 31 BC at the Battle of Actium.[90] Antony and Cleopatra were able to flee through a gap in the line, which was the plan, but most of his fleet did not follow and returned to port. After the battle, most of his forces in Greece surrendered.[91]

After a number of defections to Octavian – both Roman governors and client kings – through the winter of 31 and 30 BC, Antony's remaining forces were only those in the Ptolemaic Kingdom.[92] Troubled by demands from his soldiers for land, and only able to solve them with large-scale land purchases, Octavian marched on Egypt in pursuit of its booty. He marched overland on the Mediterranean coast. He engaged negotiations with Cleopatra but they broke down by July 30 BC.[93] Later that month, Octavian arrived at Alexandria and on 1 August, took and sacked the city.[94] He killed Caesarion and Antony's heir, Antyllus, but captured Cleopatra's children for his triumph. Cleopatra and Antony committed suicide.[95]

Legacy

In formation of the Principate

The ascendancy of Octavian at the triumvirate's close was closely followed by his constitutional "settlements" and the formation of the Principate and the Roman empire.[96] The creation of the triumvirate and its system of absolute rule, however, was not then known to be permanent. Even in the imperial period, writers like Tacitus reflected on how the republic had been dominated by single men before.[97] Moreover, it was not inevitable that the triumvirs were going to defeat the liberatores.[98] Their successful campaign, culminating at Philippi, was recognised in coming generations as a turning point in the republic's history. Tacitus, for example, dates the end of the republic to the triumviral victory there, which left the republic defenceless and nulla iam publica arma (i.e., the republic was disarmed).[99][100] Erich Gruen, in Last generation of the Roman republic, attributes the republic's collapse to the long and brutal conflicts after Caesar's assassination, largely fought by (and then between) the triumvirs, which eventually "made it impossible to pick up the pieces".[101]

The mass violence of triumviral rule and their untraditional form of government was contemporaneously seen as illegitimate.[102] To combat such charges, the triumvirs attempted to preserve the appearance of republican practices and legality.[102] Of course, the extent to which the triumvirate heeded republican traditions changed over time. Over time, as the political situation stabilised, Octavian in Rome resumed the normal operation of the consulship (rather than appointment of many and multiple suffect consulships in a single year).[103]

The traditional magistrates did not yield all of their duties to the triumvirs; they were still expected to and did conduct public business. Moreover, the consuls still exercised some degree of independent political authority.[104] The traditional means of moving legislation before the senate and the assemblies also was not abandoned: the triumvirs moved multiple laws before the people on diverse subjects such as extending citizenship, ratification of Antony's eastern settlements, extension of the triumvirate, and expanding the patriciate.[105] While the mere operation of the republic's institutional machinery did not represent a free state, the triumvirs made a show of following traditional legal niceties.[106] The triumvirs at various times also made repeated promises or offers to give their powers back to the senate and people, though of course these promises were never kept.[107] Most especially, the triumvirs' powers to appoint all provincial governors served as part of the division between military and civic provinces later adopted in Augustus' political settlements.[108]

In Roman culture

The political chaos of the triumviral years proved a ladder for many provincials, veterans, and former slaves. Many of the great works of Latin literature were produced in this unstable period, such as Horace's Epodes and Satires, Virgil's Eclogues and Georgics, and the histories of Sallust and Asinius Pollio.[102] The political competition between Octavian and Antony provided the impetus for Octavian's ally, Gaius Maecenas, to support many leading artists of his day.[109]

Virgil's Eclogues, for example, shed light on the fears of shepherds and herdsmen in rural Italy during Octavian's land confiscations when he sought lands to settle veterans in the aftermath of Philippi. The proscriptions also proved a topic of embellishment; many stories are told of the plight of victims and their attempts to escape. Cicero's plight during the proscriptions, especially, was a recurrent topic in ancient schools of oratory.[110]

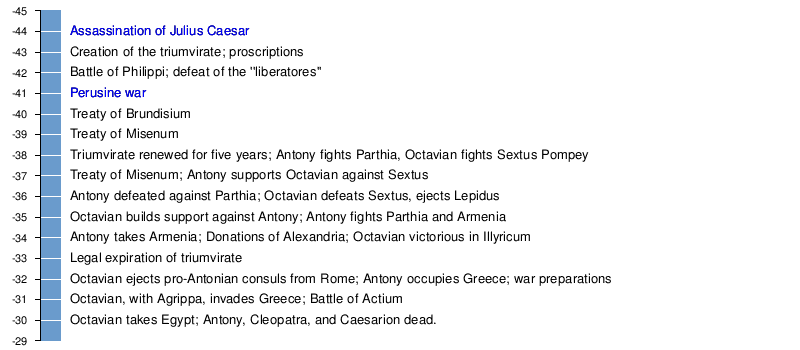

Timeline

The following years are taken from the narrative in Pelling 1996.

See also

- Triumvirate § Modern triumvirates named after the Roman one

References

Citations

- ^ a b Cadoux & Lintott 2012.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, p. 511.

- ^ Ridley, R (1999). "What's in the Name: the so-called First Triumvirate". Arctos: Acta Philological Fennica. 33: 133–44. Specifically, "first triumvirate" is first attested in 1681.

- ^ Russell, Amy (30 June 2015). "Triumvirate, First". Encyclopedia of Ancient History. Wiley. pp. 1–3. doi:10.1002/9781444338386.wbeah26425. ISBN 978-1-4051-7935-5.

- ^ Tempest 2017, p. 241; Goldsworthy 2006, p. 509.

- ^ Tempest 2017, p. 242.

- ^ Rawson 1992, p. 474. The bill was "trebly irregular because it was not a dies comitialis, due notice had not been given, and violence was used".

- ^ a b Rawson 1992, p. 475.

- ^ Rawson 1992, p. 477.

- ^ Rawson 1992, p. 479.

- ^ Tempest 2017, p. 243.

- ^ Rawson 1992, p. 483.

- ^ Rawson 1992, p. 485.

- ^ a b c d Rawson 1992, p. 486.

- ^ Welch, Kathryn (2014). "The lex Pedia of 43 BCE and its aftermath". Hermathena (196/197): 137–162. ISSN 0018-0750. JSTOR 26740133.

- ^ Vervaet 2020, pp. 24, 30.

- ^ Broughton 1952, pp. 337, 340.

- ^ Vervaet 2020, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Vervaet 2020, pp. 34–35, also noting a connection between the Second Triumvirate's legislative powers and the powers of triumvirates established with constitutive powers for Roman colonies.

- ^ Vervaet 2020, p. 39, summum imperium auspiciumque.

- ^ Vervaet 2020, p. 46.

- ^ Vervaet 2020, p. 36; Pelling 1996, p. 1.

- ^ Millar 1973, pp. 51 et seq.

- ^ Vervaet 2020, p. 39.

- ^ Vervaet 2020, p. 32.

- ^ Rawson 1992, p. 486, citing App. BCiv., 4.8–11.

- ^ Thein 2018, citing App. BCiv., 4.5.

- ^ Thein 2018.

- ^ a b Pelling 1996, p. 5.

- ^ Pelling 1996, pp. 5–6.

- ^ Pelling 1996, p. 6.

- ^ Tempest 2017, pp. 245–46.

- ^ Pelling 1996, pp. 6–7. "It would surely have been better to move west quickly... and seek to isolate the advanced force on the west coast of Greece [and] play the 48 campaign over again ... the Liberators' brutal treatment [of Asia] did nothing for their posthumous moral reputation. Perhaps it also cost them the war".

- ^ Pelling 1996, pp. 7–8.

- ^ a b c Pelling 1996, p. 8.

- ^ Tempest 2017, pp. 203–4.

- ^ Pelling 1996, p. 8; Tempest 2017, p. 202.

- ^ Tempest 2017, p. 208.

- ^ Pelling 1996, p. 9.

- ^ Pelling 1996, pp. 9–10.

- ^ Pelling 1996, p. 10.

- ^ Pelling 1996, pp. 10–11.

- ^ Pelling 1996, pp. 11–12.

- ^ Pelling 1996, p. 12.

- ^ Pelling 1996, p. 13.

- ^ Pelling 1996, pp. 13–14.

- ^ Pelling 1996, p. 14.

- ^ Pelling 1996, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Pelling 1996, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Pelling 1996, p. 16.

- ^ a b Pelling 1996, p. 17.

- ^ a b Pelling 1996, p. 18.

- ^ Pelling 1996, p. 19.

- ^ a b Pelling 1996, p. 20.

- ^ Pelling 1996, pp. 20–21.

- ^ a b Pelling 1996, p. 21.

- ^ Pelling 1996, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Pelling 1996, p. 23.

- ^ a b Pelling 1996, p. 24.

- ^ Pelling 1996, p. 25.

- ^ Pelling 1996, p. 26, citing Plut. Ant., 35, among others.

- ^ Pelling 1996, p. 26.

- ^ Pelling 1996, pp. 26–27.

- ^ Pelling 1996, p. 27.

- ^ Pelling 1996, p. 28.

- ^ Pelling 1996, p. 30.

- ^ Pelling 1996, p. 31.

- ^ Pelling 1996, p. 32.

- ^ a b Pelling 1996, p. 33.

- ^ a b c d Pelling 1996, p. 34.

- ^ Pelling 1996, p. 35.

- ^ Pelling 1996, p. 36.

- ^ Pelling 1996, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Pelling 1996, p. 38.

- ^ Pelling 1996, p. 37.

- ^ Pelling 1996, p. 39.

- ^ Pelling 1996, p. 40.

- ^ Pelling 1996, pp. 40–41.

- ^ Pelling 1996, p. 42.

- ^ Pelling 1996, p. 43.

- ^ Pelling 1996, pp. 46–47.

- ^ This is disputed. Pelling 1996, pp. 67 et seq discusses the matter. Aug. RG, 7.1 implies he held the trimvirate continually for ten years, which Pelling finds "decisive". Others argue that the triumvirate, as a magistracy without a specific term, ended only with the abdication of its members; Octavian abdicated in 27 BC, long after expiration of the second quinquennium. Vervaet 2020, pp. 29–32.

- ^ Pelling 1996, pp. 48–49.

- ^ Pelling 1996, p. 50, noting that some scholars, including Syme, infer more than 300 senators; Pelling calls that inference "most precarious".

- ^ Pelling 1996, p. 50.

- ^ Pelling 1996, p. 51.

- ^ Pelling 1996, p. 52.

- ^ Pelling 1996, pp. 52–54.

- ^ Pelling 1996, p. 56.

- ^ Pelling 1996, pp. 57–58.

- ^ Pelling 1996, p. 59.

- ^ Pelling 1996, p. 61.

- ^ Pelling 1996, p. 62.

- ^ Pelling 1996, p. 63.

- ^ Pelling 1996, pp. 64–65.

- ^ Scholars over the last decades have increasingly challenged the older view that Augustus "restored the republic whilst hiding his powers behind [a] façade". They emphasise that the "Principate" emerged only with Tiberius' success in making the position hereditary. See eg Cooley, Alison (24 February 2022). "Augustus, Roman emperor, 63 BCE–14 CE". Oxford Classical Dictionary. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199381135.013.979. ISBN 978-0-19-938113-5. Retrieved 30 September 2022.

- ^ Pelling 1996, p. 1, citing Tac. Ann. 1.

- ^ Rawson 1992, p. 488. "The cause of the 'liberators' might have triumphed; its defeat at Philippi was not a foregone conclusion".

- ^ Rawson 1992, p. 488.

- ^ Tacitus (1931). Annals. Loeb Classical Library 249. Vol. 3. Translated by Moore, Clifford H. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. 2. ISBN 978-0-674-99274-0.

- ^ Gruen, Erich (1995). The last generation of the Roman republic. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 504. ISBN 0-520-02238-6.

- ^ a b c Welch 2016.

- ^ Millar 1973, p. 52.

- ^ Millar 1973, p. 53, citing App. BCiv., 4.37 (mentioning that Lucius Munatius Plancus passed legislation striking some victims from the proscription lists).

- ^ Millar 1973, p. 53.

- ^ Millar 1973, p. 54.

- ^ Millar 1973, pp. 54, 65.

- ^ Millar 1973, p. 62.

- ^ Welch 2016; Pelling 1996, p. 45.

- ^ Beard, Mary (2015). SPQR: a history of ancient Rome (1st ed.). New York: Liveright Publishing. pp. 341–344. ISBN 978-0-87140-423-7. OCLC 902661394. Also references App. BCiv., 4 and Sen. Suas., 6–7 (on Cicero).

Modern sources

- Beard, Mary (2015). SPQR: a history of ancient Rome (1st ed.). New York: Liveright Publishing. ISBN 978-0-87140-423-7. OCLC 902661394.

- Broughton, Thomas Robert Shannon (1952). The magistrates of the Roman republic. Vol. 2. New York: American Philological Association.

- Cadoux, Theodore John; Lintott, Andrew (2012). "triumviri". In Hornblower, Simon; et al. (eds.). The Oxford classical dictionary (4th ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199381135.013.6576. ISBN 978-0-19-954556-8. OCLC 959667246.

- Crawford, Michael (1974). Roman Republican Coinage. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-07492-6. OCLC 450398085.

- Goldsworthy, Adrian (2006). Caesar: Life of a Colossus. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-13919-8.

- Millar, Fergus (1973). "Triumvirate and Principate". The Journal of Roman Studies. 63: 50–67. doi:10.2307/299165. ISSN 0075-4358. JSTOR 299165. S2CID 161712594.

- Pelling, C (1996). "The triumviral period". In Bowman, Alan K; Champlin, Edward; Lintott, Andrew (eds.). The Augustan empire, 43 BC–AD 69. Cambridge Ancient History. Vol. 10 (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–69. ISBN 0-521-26430-8.

- Rawson, Elizabeth (1992). "The aftermath of the Ides". In Crook, John; Lintott, Andrew; Rawson, Elizabeth (eds.). The last age of the Roman Republic, 146–43 BC. Cambridge Ancient History. Vol. 9 (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 468–90. ISBN 0-521-85073-8. OCLC 121060.

- Tempest, Kathryn (2017). Brutus: the noble conspirator. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-18009-1. OCLC 982651923.

- Thein, Alexander (2018). "Proscriptions". The Encyclopedia of Ancient History. Wiley. pp. 1–2. doi:10.1002/9781444338386.wbeah30481. ISBN 9781405179355. S2CID 242094148.

- Vervaet, Fredrick (2020). "The triumvirate rei publicae constituendae". In Pina Polo, Francisco (ed.). The triumviral period: civil war, political crisis and socioeconomic transformations. Prensas de la Universidad de Zaragoza. pp. 23–48. ISBN 9788413400969.

- Welch, Kathryn (2016). "Triumvirate, Second". The Encyclopedia of Ancient History. Wiley. pp. 1–3. doi:10.1002/9781444338386.wbeah30085. ISBN 9781405179355.

Ancient sources

- Appian (1913) [2nd century AD]. Civil Wars. Loeb Classical Library. Translated by White, Horace. Cambridge: Harvard University Press – via LacusCurtius.

- Augustus (1924) [before AD 14]. Res Gestae Divi Augusti. Loeb Classical Library. Translated by Shipley, Frederick W. Cambridge: Harvard University Press – via LacusCurtius.

- Dio (1914–27) [2nd century AD]. Roman History. Loeb Classical Library. Translated by Cary, Earnest. Cambridge: Harvard University Press – via LacusCurtius.

- Plutarch (1920) [1st century AD]. Life of Antony. Loeb Classical Library. Vol. 9. Translated by Perrin, Bernadotte. Cambridge: Harvard University Press – via LacusCurtius.

- Seneca (1928) [1st century AD]. Suasoriae of Seneca the Elder. Translated by Edward, WA. Cambridge University Press – via Attalus.

External links

- Lendering, Jona (2003). "Second Triumvirate". Livius.org. Retrieved 26 November 2022.

- Wasson, Donald L (2016). "Second Triumvirate". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 26 November 2022.