Scythian genealogical myth

The Scythian genealogical myth was an epic cycle of the Scythian religion detailing the origin of the Scythians. This myth held an important position in the worldview of Scythian society, and was popular among both the Scythians of the northern Pontic region and the Greeks who had colonised the northern shores of the Pontus Euxinus.[1]

Narrative

Five variants of the Scythian genealogical myth have been retold by Greco-Roman authors,[2][3][1][4][5] which all traced the origin of the Scythians to the god Targī̆tavah and to the Scythian Snake-Legged Goddess:[6][7][8]

- Herodotus of Halicarnassus's recorded two variants of the myth, and according to his first version, one thousand years before the Scythians were invaded by the Persians in 513 BC, the first man born in hitherto desert Scythia was named Targitaos and was the son of "Zeus" (that is the Scythian Sky-god Pāpaya) and a daughter (that is the Scythian Earth-goddess Api) of the river Borysthenēs. Targitaos in turn had three sons, who each ruled a different part of the kingdom, named:

- Lipoxais (Ancient Greek: Λιποξαις, romanized: Lipoxais; Latin: Lipoxais)

- Arpoxais (Ancient Greek: Αρποξαις, romanized: Arpoxais; Latin: Arpoxais)

- Kolaxais (Ancient Greek: Κολαξαις, romanized: Kolaxais; Latin: Colaxais)

- One day three gold objects – a battle-axe, a plough with a yoke, and a drinking cup – fell from the sky, and each brother in turn tried to pick the gold, but when Lipoxais and Arpoxais tried, it burst in flames, while the flames were extinguished when Kolaxais tried. Kolaxais thus became the guardian of this sacred gold (the hestiai of Tāpayantī), and the other brothers decided that he should become the high king and king of the Royal Scythians while they would rule different branches of the Scythians.

- According to the second version of the myth recorded by Herodotus, Hēraklēs arrived in deserted Scythia with Gēryōn's cattle. Because of the extremely cold weather of Scythia, Hēraklēs covered himself with his lion skin and went to sleep. When Hēraklēs woke up, he found that his mares had disappeared, and he searched for them until he arrived at a land called the Woodland (Ancient Greek: Υλαια, romanized: Hulaia; Latin: Hylaea), where in a cave he found a half-maiden, half-viper being who later revealed to him that she was the mistress of this country, and that she had kept Hēraklēs's horses, which she agreed to return them only if he had sexual intercourse with her. She returned his freedom to Hēraklēs after three sons were born of their union:[11]

- Agathyrsos (Ancient Greek: Αγαθυρσος, romanized: Agathursos; Latin: Agathyrsus)

- Gelōnos (Ancient Greek: Γελωνος, romanized: Gelōnos; Latin: Gelonus)

- Skythēs (Ancient Greek: Σκυθης, romanized: Skuthēs; Latin: Scythes)

- Before Hēraklēs left Scythia, the serpent maiden asked him what should be done once the boys had reached adulthood, and he gave her his girdle and one of his two bows, and told her that they should be each tasked with stringing the bow and putting on the girdle in the correct way, with whoever succeeded being the one who would rule his mother's land while those who would fail the test would be banished. When the time for the test had arrived, only the youngest of the sons, Skythēs, was able to correctly complete it, and he thus became the ancestor of the Scythians and their first king, with all subsequent Scythian kings claiming descent from him. Agathyrsos and Gelōnos, who were exiled, became the ancestors of the Agathyrsoi and Gelōnoi.

- A third variant of the myth, recorded by Gaius Valerius Flaccus, described the Scythians as descendants of Colaxes (Latin: Colaxes), who was himself a son of the god Iūpiter with a half-serpent nymph named Hora.

- The fourth variant of the myth, recorded by Diodorus of Sicily, calls Skythēs the first Scythian and the first king, and describes him as a son of "Zeus" and an earth-born viper-limbed maiden.

- The fifth version of the myth, recorded in the Tabula Albana, recorded that after Hēraklēs had defeated the river-god Araxēs, he fathered two sons with his daughter Echidna, who were named Agathyrsos and Skythēs, who became the ancestors of the Scythians.[14]

| Family tree of the Scythian gods | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Among the two versions of the genealogical myth recorded by Herodotus of Halicarnassus, the first one was the closest to the original Scythian form, while the second one was a more Hellenised version which had been adapted to fit Greek mythological canons.[15]

Some regional variations of the genealogical myth might have existed in Scythia, including possibly one which placed the setting of the myth near the mouth of the Tyras river, at the location of the city of Tyras, which was initially called "the snake-filled" (Ancient Greek: Οφιουσσα, romanized: Ophioussa) by the Greeks, possibly because the local inhabitants claimed that the home of the serpent-legged Scythian ancestral goddess was located there rather than at Hylaea.[16]

The myth of the golden objects which fell from the sky was also present among other Scythic peoples such as the Saka of Central Asia, and therefore must have been an ancient Iranian tradition.[17]

Interpretation

The Snake-Legged Goddess

The serpent-mother's traits are consistent across the multiple versions of the genealogical myth and include her being the daughter of either a river-god or of the Earth and dwelling in a cave, as well as her being half-woman and half-snake.[18][19] The Scythian foremother was also an androgynous goddess who was often represented in art as being bearded.[20]

The Snake-Legged Goddess was thus a primordial ancestress of humanity,[21] which made her a liminal figure who founded a dynasty, and was therefore only half-human in appearance while still looking like a snake, itself being a creature capable of passing between the worlds of the living and of the dead with no hindrance.[22]

The snake aspect of the goddess is linked to the complex symbology of snakes in various religions due to their ability to disappear into the ground, their venom, the shedding of their skin, their fertility, and their coiling movements, which are associated with the underworld, death, renewal, and fertility:[23] being able to pass from the worlds above and below the earth, as well as of bringing both death and prosperity, snakes were symbols of fertility and revival.[24] The legs of the goddess were sometimes instead depicted as tendrils, which also had a similar function by representing fertility, prosperity, renewal, and the afterlife because they grow from the Earth within which the dead were placed and blossom again each year.[25][24]

The Snake-Legged Goddess was also a feminine deity who appeared in an androgynous form in ritual and cult, as well as in iconography and ritual. This androgyny represented the full inclusiveness of the Snake-Legged Goddess in her role as the primordial ancestress of humanity.[21] The androgyny of the Snake-Legged Goddess also enhanced her inherent duality represented by her snake and tendril limbs.[24]

The role of the Snake-Legged Goddess in the genealogical myth is not unlike those of sirens and similar non-human beings in Greek mythology, who existed as transgressive women living outside of society and refusing to submit to the yoke of marriage, but instead chose their partners and forced them to join her. Nevertheless, unlike the creatures of Greek myth, the Scythian serpent-maiden did not kill Hēraklēs, who tries to win his freedom from her.[26]

The identification of the father of the Snake-Legged Goddess with the river-god Araxes corresponds to the non-mythological origin of the Scythians as recorded by Herodotus of Halicarnassus, according to which the Scythians initially lived along the Araxes river until the Massagetae expelled them from their homeland, after which they crossed the Araxes river and migrated westwards.[27]

The myth of Aphroditē Apatouros

The Scythian genealogical myth was a continuation[28] of the legend of Aphroditē Apatouros (Αφροδιτη Απατουρος) and the Giants as recorded by Strabo, according to which the goddess Aphroditē Apatouros had been attacked by Giants and called on Hēraklēs for help. After concealing Hēraklēs, the goddess, under guise of introducing the Giants one by one, treacherously handed them to Hēraklēs, who killed them.[29] Aphroditē Apatouros and "Hēraklēs" then buried the Giants under the earth, due to which volcanic activity remained a constant in the region of Apatouron.[30]

Aphroditē Apatouros was the same goddess as the Snake-Legged Goddess of the Scythian genealogical myth, while "Hēraklēs" was in fact Targī̆tavah, and her reward to him for defeating the Giants was her love.[29]

The Greek poet Hesiod might have mentioned this legend in the Theogony, where he assimilated the Snake-Legged Goddess to the monstrous figure of Echidna from Greek mythology. In Hesiod's narrative, "Echidna" was a serpent-nymph living in a cave far from any inhabited lands, and the god Targī̆tavah, assimilated to the Greek hero Hēraklēs, killed two of her children, namely the Hydra of Lerna and the lion of Nemea. Thus, in this story, "Hēraklēs" functioned as a destroyer of evils and a patron of human dwellings located in place where destruction had previously prevailed.[31]

"Hēraklēs"

The "Hēraklēs" of Herodotus of Halicarnassus's second version and from the Tabula Albana's version of the genealogical myth is not the Greek hero Hēraklēs, but the Scythian god Targī̆tavah, who appears in the other recorded variants of the genealogical myth under the name of Targitaos or Skythēs as a son of "Zeus" (that is, the Scythian Sky Father Papaios), and was likely assimilated by the Greeks from the northern shores of the Black Sea with the Greek Hēraklēs[1] because of his important role in the foundational myths of the Greek colonists throughout the Mediterranean basin.[32]

The arrival of "Hēraklēs" in the deserted Scythia corresponds to the mythical motif of the conquest of the empty land by the brave invader, while the stealing of his mares by the serpent maiden corresponds to the cattle-raid motif of Indo-Iranic mythology.[33]

The reference to "Hēraklēs" driving the cattle of Gēryōn also reflects the motif of the cattle-stealing god widely present among Indo-Iranic peoples,[1][34] and the reference to him stealing Gēryōn's cattle after defeating him in Herodotus of Halicarnassus's second version of the genealogical myth and of his victory against the river-god Araxēs in the Tabula Albana's version were Hellenised versions of an original Scythian myth depicting the typical mythological theme of the fight of the mythical ancestor-hero, that is of Targī̆tavah, against the chthonic forces, through which he slays the incarnations of the primordial chaos to create the Cosmic order.[1]

The Hellenised myth of Targī̆tavah staying in Scythia might have been recorded in the Orpheōs Argonautika, which mentions a bull-riding cattle-thief Titan, who, in this Hellenised narrative, might have been "Hēraklēs," to whom Targī̆tavah was identified, and who created the Cimmerian Bosporus by cutting a passage from the Maeotian swamp.[35]

The stolen horses and the bow of Targī̆tavah in the second variant of the genealogical myth connected him to the equestrianism and archery of the Scythians.[36]

The peoples of Scythia believed that Targī̆tavah had left a two-cubit long[37] footprint in the territory of the Tyragetae, in the region of the middle Tyras river, which the local peoples of this area displayed proudly.[38] Since only gods were able to leave footprints on the hard rock, this footprint was held as a sign of divine protection,[39] and, being the ancestor of the Scythians, he became their protector and laid claim to their country and all of its inhabitants for eternity by pressing his footprint into the Scythian rock.[40]

Targī̆tavah might also have been identified by the Greeks in southern Scythia with Achilles Pontarkhēs (lit. 'Achilles, Lord of the Pontic Sea'), in which role he was associated with the Snake-Legged Goddess and was the father of her three sons.[41]

Cosmogenesis

This myth explained the origin of the world,[42] and therefore begun with the Heaven father Pāpaya and the Earth-and-Water Mother Api being already established in their respective places, following the Iranic cosmogenic tradition. This was followed by the process of creation proper through the birth of the first man, Targī̆tavah.[43]

Ethnogenesis

The Scythian genealogical myth also ascribed the origin of the Scythians to the Scythian Sky Father Papaios, either directly or through his son Targī̆tavah, and to the Snake-Legged Goddess affiliated to Artimpasa,[44] and also represented the threefold division of the universe into the Heavens, the Earth, and the Underworld, as well as the division of Scythian society into the warrior, priest, and agriculturalist classes.[45]

The desert

The original deserted state of the land of Scythia when Targī̆tavah first arrived there in the myth followed the motif of the primordial state of the land, which was devastated and barren before the first king finally ended this state of chaos by establishing the tilling of the land and the practice of agriculture.[46] One of the themes of both Herodotean versions of the Scythian genealogical myth as well as of the other Scythian origin myth known as the "Polar Cycle" is that of the Scythians' occupation of the virgin land.[47]

The sons of Targī̆tavah

Lipoxais, Arpoxais, and Kolaxais

The names of Targī̆tavah's sons in the first version of the genealogical myth – Lipoxais, Arpoxais, and Kolaxais – end with the suffix "-xais," which is a Hellenisation of the Old Iranian term xšaya meaning ruler:[45][48][49][50]

- Lipoxais, from Scythian *Lipoxšaya, from an earlier form *Δipoxšaya, means "king of radiance," in the sense of "king of the sun."[51]

- The first element, *δipa-, is derived from the Indo-European root dyew-, meaning "to be bright" a well as "sky" and "heaven," and can also give the name the meaning of "king of heaven."[51]

- Arpoxais, from Scythian *R̥buxšaya, means "king of the skillful" and "king of the toilers," as well as "king of the airspace."[52]

- Kolaxais, from Scythian *Kolaxšaya, means "poleaxe-wielding king" or "hammer-wielding king," as well as "sceptre-wielding king," "thunderer king," and "blacksmith king," with the latter meaning "ruling king of the lower world."[53]

The layers of the cosmos

The names of the three sons of Targī̆tavah therefore corresponded to the three layers of the cosmos:[54]

- Lipoxšaya was the "King of Radiance," and therefore of the Heavens;

- R̥buxšaya was the King of the Airspace, and therefore of lightning;

- Kolaxšaya was the Poleaxe/Hammer/Sceptre-wielding King and the Thunderer and Blacksmith king, and therefore of the Lower World.

Progenitors of the social classes

The genealogical myth also represented the formation of the three social classes of Scythian society, namely the warrior-aristocracy, the clergy, and the peasantry,[42] with each of the sons of Targī̆tavah being forebears of social classes constituting the Scythian people:[55][7][56][57][58]

- Lipoxšaya was the ancestor of the Aukhatai (Ancient Greek: Αυχαται, romanized: Aukhatai; Latin: Auchatae);

- The original Scythian form of the Hellenised name Aukhatai might have been *Vahuta, meaning "the blessed ones" or "the holy ones."[59]

- R̥buxšaya was the ancestor of the Katiaroi (Ancient Greek: Κατιαροι, romanized: Katiaroi; Latin: Catiari) and the Traspies (Ancient Greek: Τρασπιες, romanized: Traspies; Latin: Traspies);

- Kolaxšaya was the ancestor of the Paralatai (Ancient Greek: Παραλαται, romanized: Paralatai; Latin: Paralatae), also known as the Royal Scythians, who were the warrior-aristocracy of the Scythians.

- The name Paralatai was a Greek reflection of the Scythian name Paralāta, which was a title held by the Scythian warrior-aristocracy to which the kings belonged, with the kings being members of the Paralāta, although not all the Paralāta were kings. The name Paralāta was a cognate of the Avestan title Paraδāta (𐬞𐬀𐬭𐬀𐬜𐬁𐬙𐬀), which means "first created."[1][60][61][50]

The three sons of Targī̆tavah represented the division of Scythian society into a system of tripartite classes which existed among all the Indo-European peoples, and is well-attested among the Indo-Iranic peoples, such as the pištra three-fold class system of Zoroastrianism, as well as the varṇa system of the Indic peoples which divided the societies of the Indic peoples into the clerical class of the brāhmaṇa, the military aristocracy of the kṣatriya to which belonged the warriors and kings, and the wealth-producing ordinary community members of the vaiśya.[1][62]

These three classes, in turn, each corresponded to the typically Indo-Iranic tripartite structure of the universe of Scythian cosmology,[63] which is also present in the Vedic and Avestan traditions, and according to which the universe was composed of the heavens, the airspace, and the earth.[64]

The three sons of Targī̆tavah were thus ancestors of the various social classes of Scythian society who also represented the three levels of the Cosmos: the upper celestial realm, the middle sphere of the airspace, and the lower terrestrial world, with the central son representing the airspace linking the two others, which also parallels the roles of the Sky Father Papaios, the Earth-and-Water Mother Api, and their child, Targī̆tavah, that is the airspace.[1]

The warrior class

The Scythian genealogical myth thus assigned to the Scythian kings a divine ancestry through descent from Kolaxšaya, as attested when the Scythian king Idanthyrsus claimed Papaios as his ancestor.[65] The name Paralatai was a Greek reflection of the Scythian name Paralāta, which was a title held by Scythian kings, and was also a cognate of the Avestan title Paraδāta (𐬞𐬀𐬭𐬀𐬜𐬁𐬙𐬀), which means "first created."[1][61][50]

According to the version of the genealogical myth recorded by Gaius Valerius Flaccus, Kolaxšaya and his warriors decorated their shields with "fires divided into three parts," flashing lightning, and pictures of red wings, with the colour red being characteristic of the warrior class in Indo-Iranic tradition.[1][66]

The priestly class

In Gaius Valerius Flaccus's narrative, Auchus, that is Lipoxšaya, was born with white hair and wore a band which passed around his head three times and whose ends hanged backwards, with the colour white in Indo-Iranic tradition being that of priesthood, and the headband of Auchus being part of a priest's regalia which was depicted in the art of the various ancient Iranian peoples. These thus signalled Lipoxšaya as the progenitor of Aukhatai, that is the priestly component of Scythian society's tripartite class system.[1]

The farmer class

R̥buxšaya, meanwhile, was the progenitor of the Katiaroi and Traspies, who formed the third section of the Scythian class system, that of the ordinary populace consisting of farmers and horse-breeders.[1]

The sub-division of the farmer class into two groups, namely the Katiaroi connected to cattle the Traspies connected to horses, fits an Indo-Iranic motif of which the other iterations include the Zoroastrian Gə̄uš Uruuan (whose name means "the soul of the cow") and Druuāspā (whose name means "(the deity) with healthy horses"), as well as the Vedic Aśvins and their sons in later Hindu tradition, Nakula and Sahadeva.[67] The name of the Traspies, likely derived from Scythian Trāspā, meaning "three horses," is also semantically connected to that of the Aśvins.[68]

The gold objects and the class structure

The three golden objects which fell from the sky also represented the various Scythian classes:[1][69][70]

- the battle-axe represents the warrior-aristocracy;

- the battle-axe also functioned as a royal sceptre or staff[71]

- the cup, used during religious rituals for offering libations and to prepare haoma, representing the priestly class;

- the plough used by farmers to till the fields and the yoke associated with cattle-breeding represented the lowest class of the Katiaroi and Traspies.

The golden objects, that is the hestiai of Tāpayantī, as attested by their fiery nature, were the fires of the three classes of Scythian society, with the triunity of the Scythian hestiai representing the concept of fire, represented by the goddess Tāpayantī, being the primeval and all-encompassing element permeating the world and being present throughout it.[1][72]

Although each of the three gold objects each corresponded to one of the three layers of the Scythian tripartite class structure, the fact that they all came into the possession of Kolaxšaya and his descendants meant that they had no connections to his elder brothers who also corresponded to two of the three Scythian social classes.[73]

The plough-and-yoke and the cup, although representing the farmer and priestly functions, were instead symbols of royal power used in the coronation rites of the Scythian king, which themselves found a parallel in the rājasūya consecration ceremony of Indic kings.[74] The acquisition of the objects by Kolaxšaya represented the Scythian royal coronation ritual, according to which the world order was disturbed by the death of the previous king and was restored through the coronation of the new king.[75]

The falling of the three objects from the sky and Kolaxšaya coming to possessing them was also a myth of the transfer of power from the older generation of gods to the newer one, similar to power leaving Ouranos in ancient Greek religion and Varuṇa in ancient Vedic religion to pass on to the newer generations.[76]

Kingship

Kingship and the fārnā

The Scythian genealogical myth was a variant of an old Indo-European tradition present among the Indo-Iranic peoples, especially those who were part of the steppe cultures, according to which the royal dynasty and, by extension, the nation itself, were born from the union of a serpent-nymph and a travelling hero who was searching for his stolen horses. This motif became widely widespread in the region of the Caucasus.[77]

Therefore, the ownership of the three golden objects which fell from the sky, which constituted the hestiai of Tāpayantī, by Kolaxšaya and his descendants constituted a heaven-given manifestation of divine origin of the royal power of the Scythian kings, and of the kings' proximity to Tāpayantī.[9] The Scythian goddess Tāpayantī was herself linked to the fārnā,[78] and the ownership of her hestiai thus provided to Kolaxšaya the fārnā (Avestan: 𐬓𐬀𐬭𐬆𐬥𐬀𐬵, romanized: xᵛarᵊnah), that is the royal splendour, which among Iranic peoples was believed to transform the king into a sacred figure and a kind of deity who was sometimes believed to be the brother of the Sun and the Moon. Among the Scythic peoples, this notion of the association of the Sun with kingship was attested by the Massagetaean practice of sacrificing horses to the Sun-god.[79]

The importance of the fārnā among the many Scythic peoples is attested by the fact that it is the most widespread element among recorded Scytho-Sarmatian names in the Pontic Steppe region.[80][78]

The hestiai of Tāpayantī were thus the physical manifestations of the fārnā and were guarded by the kings, with this association being evident in how the golden objects burnt the brothers who were unworthy of kingship, but did not harm the legitimate king, Kolaxšaya. Like the typically Iranic conceptions of the fārnā attested in the Zoroastrian and Persian myths, the Scythian fārnā was of heavenly origin, and represented an emanation of the sacred fire, and therefore could be itself depicted as objects made of or decorated with gold. It was the fārnā who chose the king, legitimised him, and guaranteed his power, while the king himself was seen as being unable of being burnt like fire.[81]

The Scythian concept of the fārnā was thus tripartite, with all of its three components belonging together to the king, although they could leave the king if he became unworthy. The three components of the fārnā also represented an emanation of the celestial fire and each corresponded to one of the three social classes of Scythian society, and were worshipped in religious rites.[82]

All Iranic peoples considered gold to be a symbol of fārnā and its material incarnation, as well as the metal of the warrior-aristocracy, with the ownership of the fārnā in the form of gold being necessary for a warrior to be victorious. Thus, the connection of the fārnā and gold with the king represented its connection to the warrior-aristocracy to which the kings belonged.[83] In consequence, Iranic kings surrounded themselves with gold, which was supposed to help them preserve their fārnā,[83] hence why Scythian kings only used gold cups, which represented the priestly role of royal power. Due to this, the cups placed in the burials of the earliest Scythian kings at Kelermes were all made of gold.[84]

Because the fārnā was believed to have a solar nature, and therefore to be dangerous and capable of harming ordinary humans, the Scythian kings avoided direct contact with members of the populace, and instead communicated with them through the means of royally-appointed messengers who were buried with the kings after their deaths.[85]

Kingship and the social classes

At the same time, the Scythian physical form of the royal fārnā consisted of three objects which each represented one of the three social classes of Scythian society, with the king himself thus encompassing and transcending these classes.[86][70]

The narrative of the ancestor of the Paralāta, Kolaxšaya, succeeding in acquiring the gold objects, that is the hestiai of Tāpayantī, which had fallen from the sky was also an explanation of the supremacy of the tribe descended from him, that is the Royal Scythians, over the other Scythian tribes, and of the Scythian kings, who bore the title of Paralāta.[1] The ownership of the hestiai of Tāpayantī thus gave to Kolaxšaya the right to rule, and they also represented the king's role whereby, as the ruler of all society, he also represented all the social classes, being this the chief warrior, the chief priest, and the chief farmer, with all three social roles united within him.[69]

This conceptualisation of the king originating from the warrior-aristocracy but at the same time encompassing the three social functions and representing all the classes by being himself the incarnation of society was one of the fundamental concepts of Indo-Iranic ideology. This practise was also present among the Indic peoples, where the king originated from the kṣatriya warrior aristocracy, and was proclaimed to be a member of the brāhmaṇa priestly caste and symbolically married the brāhmaṇa, and then did the same with the vaiśya producer caste. Other Indic coronation rites also included the symbolic birth of the king from the brāhmaṇa and vaiśya castes, thus becoming a member of all three castes at the same time. Although information about coronation rites among the Iranic peoples is meagre, this appears to have been the case among them too.[86]

Thus, the passage of the Scythian genealogical myth regarding the three brothers explained how the three sons of Targī̆tavah represented the three social classes, with the youngest of the sons, Kolaxšaya, who was the warrior, also united within himself the function of all three classes.[87] It also explained the dominant role of the warrior-aristocratic class over the other classes.[88]

The version of the Scythian genealogical myth retold by Diodorus of Sicily also made the sons of Skythes the progenitors of the social classes:[89]

- the Paloi corresponded to the warrior class of the Paralāta,

- the Napoi corresponded to the rest of the Katiaroi and Traspies.

Pliny the Elder recorded a Scythian myth, according to which a struggle between the Paloi and the Napoi resulted in the destruction of the latter by the former, representing the establishment of the supremacy of the warrior class over the producer class. Only the warrior and producer classes are mentioned in this myth because the priestly class was completely subordinate to the warrior aristocracy.[90]

Kingship and institutions

The Scythian genealogical myth originated among the royalty, and was used by the Scythian kings to establish the divine origin of their kingship and their right to rule by virtue of being the descendants of Kolaxšaya. By asserting the supremacy of the youngest brother over the elder ones, the genealogical myth also assigned such a preeminence to the Scythians, who claimed to be the "youngest of all peoples."[91][92]

The genealogical myth also ascribed to the Scythians' political and social institutions an antiquity dating back to the mythical era of the ancestors, which in the Scythian worldview was seen as ensuring the "correctness" of these institutions, which in turn guaranteed the stability and prosperity of Scythian society.[65]

In the genealogical myth, Targī̆tavah, the first man born from the union of the Heavenly Father and the Earth-and-Water Mother, represented the primordial unity. This unity incarnated by Targī̆tavah soon underwent fragmentation on the levels of kinship due to Targī̆tavah having three sons, ethnicity and territory in the form of each son founding a different tribe, and class due to the three objects representing three social classes and their respective functions. This fragmentation was finally stopped when the three objects chose Kolaxšaya, who became king when he gained possession of the gold objects which formed the totality of kingship, and his brothers proved themselves to be unworthy of possessing them and therefore became subordinate to him and the peoples descended from them became subordinate to the descendants of Kolaxšaya.[43][61][93]

After the loss of the primordial state of perfect unity, the gods sought to restore as much of this unity as feasible by choosing Kolaxšaya,[94] who thus encompassed and reintegrated the fragmented elements of the primordial totality within himself by becoming king.[61][95]

In consequence, the following Scythian kings kept the gold objects as both a royal and national treasure which acted as the symbol and legitimising source of their power and position, and which they had to renew each year through religious rituals to preserve the walfare and unity of the Scythians. Thus, priest-kings were in charge of restoring the lost primordial unity among the Scythians.[94][61][95]

The sons of Kolaxšaya

The division of the Scythian kingdom between the three sons of Kolaxšaya transposed the Scythian three-fold cosmological structure and social structure composed of three classes onto the institution of Scythian kingship, and therefore also explained the division of Scythia into three kingdoms of which the king of the Royal Scythians was the High King. Thus, Scythia was ruled by three kings, of whom one was the supreme king who guarded the hestiai of Tāpayantī. This threefold kingship is a structure recorded in historical times in Herodotus's account of the Scythian campaign of the Persian king Darius I, when the Scythians were ruled by the three kings, namely Idanthyrsus, Skōpasis, and Taxakis, with Idanthyrsus being the Scythian high king while Skōpasis and Taxakis were sub-kings.[96][2]

Kolaxšaya's partition of his kingdom among his three sons also explained the three-fold division of the Scythians into the three tribal groupings of the Royal Scythians, the Nomadic Scythians, and the Agricultural Scythians.[5]

The horse of Kolaxšaya

The mention of a "horse of Kolaxšaya" (Ancient Greek: ιππος Κολαξαιος, romanized: hippos Kolaxaios) in a partheneion, recorded by Alcman and dedicated to Artemis Orthia or the Dioscuri, suggests that Kolaxšaya possessed an unruly and fabulous horse of a fiery nature which had a white coat. This horse might have been believed to be the ancestor of all war horses.[97][98]

According to Valerius Flaccus's version of the genealogical myth, the horse of Kolaxšaya was killed by the Greek hero Jason, who then killed Kolaxšaya himself. This might reflect the passage of the Scythian genealogical myth where Kolaxšaya himself was murdered by his brothers.[13]

Agathyrsos, Gelōnos, Skythēs

The sons of Targī̆tavah according to the second version of the genealogical myth were each also ancestors of tribes belonging to the Scythian cultures:[99][57]

- Agathyrsos was the ancestor of the Agathyrsoi,

- Gelōnos was the ancestor of the Gelōnoi,

- Skythēs was the ancestor of the Scythians proper, who were named after him.

Each of the sons of Targī̆tavah in the second version of the genealogical myth respectively corresponded to the sons from the first version, with Agathyrsos corresponding to Lipoxšaya, Gelōnos corresponding to R̥buxšaya, and Skythēs corresponding to Kolaxšaya.[15]

The "horse of Kolaxšaya" from the partheneion of Alcman might alternatively have referred to Scythian horses in general due to the Scythians possibly being considered to be "Kolaxšaya-ians" because of the identification of Skythēs with Kolaxšaya.[57]

The trial of the sons

The tasks which the sons of Targī̆tavah had to perform as trial in this second version of the genealogical myth consisted of stringing a bow, and strapping a tight belt to which was attached a cup.

- The bow was a military tool, with a similar set of tools being attributes of the Indic kṣatriya, and it corresponded to the battle-axe which formed part of the hestiai of the first version of the genealogical myth. This bow was therefore used to find out which brother was the warrior and would therefore be the ancestor of the warrior class.[100]

- The belt with the cup attached to it was a sacerdotal tool, with the belt being associated to priests in Indo-Iranic tradition: adherents of Zoroastrianism had to start wearing the kustīg from a young age, attesting of the initiatic role of the belt; and the belt was also used in the initiation rites of the Indic brāhmaṇa priestly caste; therefore, the belt with a cup attacked to it represented the Scythian king's role as a priest.[101] Thus, after having proven that he was a warrior, Skythēs also obtained the cup and therefore earned the right to perform priestly functions.[102][103]

- Herodotus claimed that the Scythians of his time still wore cups hanging from their belts in memory of Skythēs.[104]

The trial of the sons of Targī̆tavah was a warrior's trial as well as a priest's trial through which Skythēs, as the king, united the social classes composing Scythian society within himself.[105] Thus, Skythēs was the first king and the progenitors of the Scythian kings.[57]

The possession of the bow of Targī̆tavah in the second version of the Scythian genealogical myth thus corresponded to the possession of the hestiai in the first version, and the function of both was to test the candidate for kingship, with these objects collectively symbolising power and the king's acquisition of them meaning that he passed the rest to become the ruler. The acquisition of the hestiai and the bow of Targī̆tavah therefore was part of the king's initiation ritual.[75]

The belt with a cup attached to it was also a symbol of royal power in multiple Iranic traditions,[106] and the cup itself was used in coronation rites among the many Indo-Iranic peoples, including the Scythians.[74] Golden cups were also placed in the burials of deceased kings.[107]

The cup and the arrows were elements of the Scythian coronation rituals, but they were also symbols of unity among the Scythians, as were the axe and spear,[74] hence why whenever the Scythians concluded a treaty of friendship, they poured wine in a cup and lowered a sword, arrows, an axe, and a spear into it.[107]

Similarly, in the story of the cauldron of Ariantas, each arrowhead represented a Scythian warrior individually, and the copper vessel standing at the Holy Ways which made from all of the arrowheads functioned as the ritual unification of the Scythians.[108]

The arrows and the cup were thus symbols of royal power used in the coronation rites of the Scythian king, which themselves found a parallel in the rājasūya consecration ceremony of Indic kings.[74] The acquisition of these objects by Kolaxšaya represented the Scythian royal coronation ritual, according to which the world order was disturbed by the death of the previous king and was restored through the coronation of the new king.[75]

The name of the Scythians

The second version of the Scythian genealogical myth also explained the origin of the name of the Scythians as being derived from that of Skythēs (Skuδa in Proto-Scythian; Skula in Scythian), whose name meant "archer," and after whom the Scythians were called Skuδatā (Skulatā in Proto-Scythian), meaning "archers."[109]

Hellenisation

The second version of the genealogical myth was one that had been Hellenised, which was not an uncommon practice of ancient Greeks done with the aim of including Barbarian peoples into the orbit of their own civilisation. Greek colonists who settled in remote peripheral regions often connected these new areas to their own myths, deities, and heroes by identifying Greek heroes with the local peoples' mythological forefathers.[28]

In Greek mythology, Hēraklēs had killed the giant Gēryōn and seized his cows, after which he sailed from Gēryōn's home island of Erytheia to Tartēssos in Iberia, from where he passed by the city of Abdēra and reached Liguria, and then going south to Italy and sailing to Sicily: on the way, he founded several cities and settlements which the Greeks supposedly later "regained." The population of new territories with characters from Greek mythology and history was thus done to justify their acquisition, and therefore the Greeks turned Hēraklēs into a founder of various nations, dynasties, and cities throughout the Oikoumenē from Iberia to India, with these feats being described in several epic Hērakleidēs which were composed and enjoyed popularity within ancient Greek society.[110]

These various stories relating Hēraklēs to various ancestral heroes of non-Greek peoples often followed the same narrative of Hēraklēs returning from Erytheia after defeating the giant Gēryōn and stealing his cattle before losing his animals due to them being stolen by an often monstrous figure, after which Hēraklēs had to reacquire his animals by challenging the thief.[111] Within the context of the Scythian genealogical myth, such a story of Hēraklēs was transposed onto the narrative of the union with the snake-maiden so as to emphasise his differences with his Scythian children, while Hēraklēs himself left nothing but a footprint in Scythia.[112]

The Hellenisation of the Scythian genealogical myth was, consequently, carried out probably by the Pontic Olbians to further their own interests among the Scythians. Therefore, the Iranic cosmological features such as the union of heaven and earth and the birth of the primordial unity represented by Targī̆tavah were ignored, and humanity as well as divisions in terms of gender, geography, status, and ethnicity had already come into existence.[113][114][92][115] Therefore, version of the Scythian genealogical legend Hellenised by the Pontic Greeks featured one of the most prominent Greek heroes and took place following his adventure on the sunset island of Erytheia where lived Gēryōn.[104]

Thus, the production of cultic propaganda for the Greek heroes and deities was done by the colonists to establish their own rights over the lands where they had settled, as well as over the areas around them and their non-Greek populations, and the figures of Hēraklēs and Achilles were important in this process among the Greeks of Olbia and Borysthenes, with Hēraklēs being made into a divine coloniser who civilised the three peoples of Scythia and becoming the father of their eponymous ancestors.[116]

The Olbia-centricity of this variant of the myth is exhibited by the mention of Hylaea, which was close to Pontic Olbia, but also by how it constituted an explanation for the cult of Targī̆tavah-Hēraklēs there.[117] Nevertheless, even this Hellenised myth still contained many Scythian elements which had equivalents in various Iranic traditions.[118]

In this version of the myth, the snake legs of the mother goddess and her dwelling place within the earth marked her as a native of Scythia. The ambiguous features of the mother goddess, such as her being both human and animal, high-ranking and base, monstrous and seductive, at the same time, corresponded to Greek perceptions of Scythian natives. Therefore, although she ruled over the land, her kingdom was empty, cold, uninhabited, and without any signs of civilisation.[119][120] Thus, her status was inferior to that of Hēraklēs in this version of the myth regarding her appearance as well as her role within the myth itself, where she followed the advice and instructions of Hēraklēs but did not decide anything.[121]

The Hellenised myth contrasted the chthonic cave-dwelling goddess with the Olympian Hēraklēs, who used the sun-chariot of Helios to complete certain of his labours and to rise to the deities of the celestial realm, and also possessed the bow of Apollo, which had similar attributes.[116]

Therefore, it was Hēraklēs, a Greek, who incarnated both the power of otherness and the otherness of power, arrived into Scythia from abroad to change the situation: in this Hellenised version of the myth, it was through union with Hēraklēs that the pre-civilised Scythia could be transformed into a world more familiar to the Greeks by the introduction of the institution of kingship.[119][120]

Meanwhile, the chthonic Scythian ancestress was later identified by the Graeco-Romans with the monstrous figure of Echidna from Hesiod's Theogony whom this latter author had located in Cilicia, which was then at the boundaries of Hesiod's known world, and whom Herodotus later located at the boundaries of his own known world, in the cold lands of Scythia that were separated from civilised eyes by the cold.[122]

Unlike the negative role of Echidna and of various snakes in Greek mythology, the partially serpentine anatomy of the "Scythian Echidna" denoted her connection with the earth, and therefore of her autochthony, and her theft of the mares of Hēraklēs was more akin to the jokes played on their lovers by beautiful maidens who were always forgiven.[123] And unlike the stories where the animals of Hēraklēs were stolen by hostile enemies, the serpent maiden instead opposed the hero's civilising march and in the end obtained an ambiguous victory by permitting him to leave a permanent sign of his passage through the descendance he had with her.[124]

Before Hēraklēs left Scythia, the mother goddess asked him whether she should settle them in her own land or send them to Hēraklēs once they have grown up, which was a way for her to ask whether the sons were to be Scythians (if they were to live with their mother) or Greeks (if they were to live with their father). Hēraklēs's response was to give them his bow, belt, and cup, which were instruments of culture, and declared that whoever among them would be able to string the bow and gird himself with the belt would become king.[125][120]

However, Hēraklēs did not claim any of the children and instead instructed that the son who passed his test and therefore was the most like Hēraklēs himself would inherit Scythia, while the other less able brothers who were therefore less like Hēraklēs would be exiled to the north, in the direction opposite to Hēraklēs's destination in Greece.[126][120]

The bow of Hēraklēs itself represented prosperity, wisdom, and life, and the trial he instructed the mother to put their sons through was meant to choose the most intelligent, skillful and strong one among them to be the king. His sacred union with the Scythian goddess also represented that of the friendly interactions of the Greeks with non-Greeks.[121]

Therefore, the addition of Hēraklēs in the second version of the genealogical myth ascribed to the Snake-Legged Goddess's sons a partial Greek ancestry, with the most youngest son proving himself to be the most worthy due to him being more Greek than his brothers through his physical prowess inherited from his father; as well as him obtaining the bow, belt and cup, which were tools of Greek culture; moreover, his inheritance of Scythia meant that he was the brother who lived the closest to the Greeks; and finally by establishing a "more virile" culture than his brothers, whose descendants, the promiscuous and luxury-loving Agathyrsi and the sedentary and farmer Gelonians, led lives which the Greeks perceived as being less masculine and therefore derived from their Asian mother.[126][120]

This Hellenised version of the Scythian genealogical myth therefore presented Skythēs as being a largely but not completely Greek figure, and, in consequence, made his Scythian descendants a people of largely Greek origin. His bow, belt, and horses which he obtained from Hēraklēs were construed in this myth as gifts thanks to which Scythian warriors obtained their offensive, defensive, and mobile capabilities, while the traits which the Greeks perceived negatively among the Scythians, Agathyrsi, and Gelonians were ascribed to their pimordial mother.[114][115]

The goal of this Hellenised Scythian genealogical myth was to impose a superiority of the Greeks over the Scythians as well as to establish a dependency of the Scythians on the Greeks regarding their "civilising" arts, and finally to portray the Scythians proper, who were more Hellenised, as being superior to their more northern and non-Hellenised neighbours such as the Agathyrsi and the Gelonians.[127][128]

The divine footprint

The inhabitants of the Greek colony of Tyras, who identified Targī̆tavah with Hēraklēs, believed that the footprint near the Tyras river had been left by Hēraklēs,[117] and that this was the location where he had attained immortality and divinity.[129] Since only gods were able to leave footprints on the hard rock, this footprint was held among the Greeks as a sign of the divinity of Hēraklēs, with such footprints being held among Greeks to represent the presence of heroes and gods at cult sites.[39]

The large size of the footprint was also linked to the ancient Greek image of gods and heroes being recognisable by their sizes and weight, so that the two cubit-long footprint could only have been left by a powerful hero whose body size corresponded to his body size, so that the achievements of Hēraklēs were only believable if they had been carried out by a hero from ancient times whose semi-divine origin manifested itself through a physique surpassing those of regular mortals of the post-mythical age.[130]

Greek influence

To propagate this more Hellenised version of the genealogical myth which turned the Scythians into a people of partly Greek origin, and to compete with the first version of the myth, the Greek artisans on the northern shores of the Black Sea produced artistic depictions of this story to distribute as trade goods to the Scythians.[114][128]

The role of Hēraklēs in Greek religion was that of a cultural hero who advanced human settlement and society by destroying incarnations of chaos, but he was also the archetype of the human conquest of death, with Gēryōn himself, whom Hēraklēs defeated, being a representation of death; this theme was continued in the myths of Hēraklēs going to the west to being the golden apples of the Hesperides and him dragging Cerberus out of the underworld. These myths transformed the figure of Hēraklēs into an unstoppable traveller who could go to the realm of Death and return from it.[131]

Therefore, the Scythian rulers saw the Greek myth of their people as descendants from Hēraklēs as an attractive one, not unlike the similar beliefs held by the kings of Sparta and Macedonia. This is attested historically when the Macedonian king Philip II requested the permission of the later Scythian king Ateas to erect a statue to Hēraklēs at the mouth of the Danube, which shows that both the Macedonian and Scythian kings commonly respected Hēraklēs.[131]

The Herodotean narrative

When Herodotus of Halicarnassus recorded the Hellenised version of the genealogical myth, he exhibited scepticism towards this narrative within his own text largely because he doubted that the Ocean encircled the earth, but also partly because he had close connections with the Western Greeks of Magna Graecia, who believed that Hēraklēs had driven the cattle of Gēryōn through their region of the world, and therefore did not accept that he had made a detour to the north to Scythia. Thus, Herodotus clarified that this was a myth told to him by the Pontic Greeks as a clarification to his Western Greek audience who would likely have been hostile to this myth.[132]

Herodotus of Halicarnassus described this footprint as being the only wonder in Scythia.[133] Its location, near the river Tyras, also had a symbolic value in the works of Herodotus, since in his worldview rivers separated not only great empires, but also the real world from the mythical world, so that anyone crossing them risked entering a strange world and could be punished through blindness.[39] The status of Scythia as being uninhabited when Hēraklēs arrived there was itself described as a liminal area between the mythical and fantastical worlds in the narrative of Herodotus; the stormy and frosty climate of Scythia, which Herodotus typically used to describe distant lands inhabited by fantastical peoples and creatures, was also such an indication of Hēraklēs entering into a liminal region.[134]

Since Herodotus perceived the Scythians and the Egyptians as being diametrical opposites, the footprint of Hēraklēs in Scythia was also the counterpart to the two cubit-long sandal of Perseus at Khemmis in Egypt: both marked places which had been sacralised by the appearance of heroes and where the divine and human realms overlapped; at the same time, while Hēraklēs had left his permanent footprint in Scythia, Perseus instead had a fleeting presence, so that the presence of his sandal in his sanctuary in Khemmis was a sign of his visit.[135]

The Herodotean record of the Scythian genealogical myth was also intended to present to his audience another group of enemies whom the Greeks' Persian enemies had faced in the form of the Scythians and to create a common picture of the Greeks and Scythians who were both invaded by the Persians as a punishment for previous wrongdoing. This narrative itself was placed by Herodotus in the framework of the "primordial struggle" between Asia and Europe which was the Trojan War.[136] Therefore, the narrative of Herodotus crafted a Greek ancestry for the Scythian "comrades" of the Greeks in their struggle against the Persians.[137]

The various Herodotean presentations of the origin of the Scythians, including both versions of the genealogical myth as well as the "Polar Cycle," were intended to present the nomadic lifestyle that enabled the Scythians to defeat the Persians as resulting from an environmental disaster in the form of a northern cold which forced them to resort to a life of wandering and to therefore be recent arrivants in the Pontic Steppe.[138]

The narrative of Hēraklēs wandering through the unfamiliar country of Scythia to search for his horse was itself recorded by Herodutus as a parallel to how the Persian army became lost and exhausted its forces while trying to pursue the Scythians during the Achaemenid invasion of Scythia in 513 BCE.[139] At the same time, the Scythians, who were presented as descendants of Hēraklēs in this story, in consequence were protected by him through his divine power to ward off evil, which was also attested through his epithet of alexikakos (αλεξικακος).[140]

Similarly, Hēraklēs reaching the abode of the Snake-Legged Goddess in the Woodland of Scythia after she abducted his horses in the myth paralleled how the Scythians intentionally drawing the Persians deeper into Scythia by laying deceptive trails.[141]

Ritual

Relics

The peoples of Scythia believed that Targī̆tavah had left his footprint in the territory of the Tyragetae, in the region of the middle Tyras river, which the local peoples of this area displayed proudly.[38] The location of this footprint was itself held to have a religious signification, since the Tyras river formed the western limit of the Eurasian steppe and its western banks were elevated, due to which the god of that river was worshipped in Scythia.[142]

The inhabitants of the Greek colony of Tyras appear to also have had their own variation of the myth of Hēraklēs passing near their city, which is suggested by the presence of the image of Hēraklēs and bulls representing the cattle of Gēryōn on this city's coins.[117]

Shrines

At Hylaea

A Greek language inscription from the later 6th century BC recorded the existence of a shrine at Hylaea which was held in common by both Scythians and Greeks. The shrine at Hylaea was the location of altars to:[143]

- the god of the Borysthenes;

- Targī̆tavah, referred to in the inscription as Hēraklēs;

- the Snake-Legged Goddess, referred to in the inscription as the "Mother of the Gods," because the Greeks identified her with their Mother Goddess Cybele due to her chthonic nature.

The inscription located this shrine in the wooded region of Hylaea, where, according to the Scythian genealogical myth, was located the residence of the Snake-Legged Goddess, and where she and Targī̆tavah became the ancestors of the Scythians; the deities to whom the altars of the shrine were dedicated to were all present in the Scythian genealogical myth. The altars at the shrine of Hylaea were located in open air, and were not placed within any larger structure or building.[144]

The Olbiopolitan Greeks also worshipped Achilles in his form identified with Targī̆tavah at Hylaea.[145]

Women performed rituals at the shrine of Hylaea,[146] and the Scythian prince Anacharsis was killed by his brother, the king Saulius, for having offered sacrifices to the Snake-Legged Goddess at the shrine of Hylaea.[147][148]

Thus, the Olbia-centricity of the Hellenised variant of the genealogical myth also constituted an origin myth for the cult of Targī̆tavah-Hēraklēs at Hylaea,[117] and the mention of the horses of "Hēraklēs" being stolen by the Snake-Legged Goddess dwelling at Hylaea explained the presence of horses in the rituals of this cult.[149]

At Tyras

A cult centre might have existed at the site of the footprint of Targī̆tavah-Hēraklēs on the Tyras river.[149]

The ritual sleep

The ritual sleep was a ceremony conducted at the Holy Ways, where the great bronze cauldron representing the centre of the world was located.[2] During this ceremony, a substitute ritual king would ceremonially sleep in an open air field along with the gold hestiai for a single night, possibly as a symbolical ritual impregnation of the earth. This substitute king would receive as much land as he could ride around in one day: this land belonged to the real king and was given to the substitute king to complete his symbolic identification with the real king, following which he would be allowed to live for one year until he would be sacrificed when the time for the next ritual sleep festival would arrive[18] and a successor of the ritual king was chosen. This ceremony also represented the death and rebirth of the Scythian king.[2]

This festival corresponded to the rājasūya royal consecration ceremony of the Indic peoples, where the borders of the king's realm were determined by the territory around which his horse walked.[108]

During the ritual sleep ceremony, the king of the Royal Scythians performed the duties of a priest, thus acting as a priest-king.[2]

The ceremony of the ritual sleep was the main event of the Scythian calendar, during which the Scythian kings would worship the gold hestiai with rich sacrifices. The ceremony might have been held at the moment of the Scythian calendar corresponding to the fall of the gold objects from the heavens.[150]

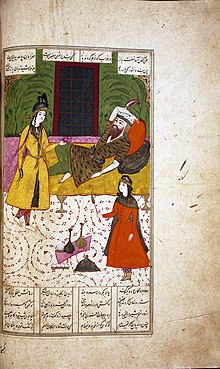

In art

The Scythian genealogical myth was often featured in Scythian art.[151]

The struggle against chaos

A Scythian depiction of the combat of Targī̆tavah against the chthonic personification of chaos might have been present on one of the bone plaques decorating a comb from the Haymanova mohyla, which was decorated with the scene of two Scythians fighting a monster with the front-legs of a lion, a scaly body, and a fish- or dragon-like split tail, with the monster's appearance connecting it to the element of water, and therefore to the chthonic realm; one of the Scythians in the scene is depicted as dying in the monster's leonine paws while the second man kills it with a spear.[1]

The trial of the sons

The narrative where the three sons of Targī̆tavah were tasked to string the bow of their father might have been represented on a silver cup from Voronezh whose surface is decorated with three scenes where Targī̆tavah explains his first son the task, then banishes his second son for failing the task, and finally gives the younger son a bow as reward for fulfilling the task.[152]

Unlike the Greek retelling of the myth, in which "Hēraklēs" returns to Greece and instructs the Snake-Legged Goddess to put their three sons through the trial of the bowstring, these scenes instead represent, in accordance with Scythian traditions of patrilineality, the divine paternal ancestor of the first king, that is Targī̆tavah himself, putting his sons through the trial.[152]

Another representation of the trial of the sons of Targī̆tavah might have decorated an electrum vessel from the Kul-Oba kurgan, where Targī̆tavah is represented wearing a Greek-type diadēma, and his two elder sons who had failed the task of the bowstring are depicted being healed while the third son is shown stringing the bow.[153]

Scythian coins

Coins of the Scythian king Eminakes struck at Pontic Olbia were decorated on their reverse with images of Targī̆tavah, who was Scythian kings' personal symbol,[103] and who was depicted on the coins as the Greek Hēraklēs wearing his lion-skin, and stringing a bow while his knee is bent.[154] Unlike other Greek coins in which Hēraklēs is depicted as an archer, his posture in the coins of Eminakes is similar to that of Targī̆tavah's son stringing the bow from the Kul-Oba vessel.[155]

Coins of the later Scythian king Ateas were struck with the image of the head of Hēraklēs wearing a lion-shaped helmet. These coins primarily copied Macedonian ones, and were meant to signal the Scythian kingdom as being an equal of the Macedonian kingdom of Philip II, although the choice of the head of Hēraklēs was also meant to emphasise Ateas's descent from Hēraklēs, who was assimilated to Targī̆tavah.[156]

Comparative mythology

Indo-Iranic parallels

Other Iranic parallels

Several parallels to the Scythian genealogical myth existed in various Iranic traditions.[155]

Zoroastrian parallels

Social classes and Zoroastrian kingship

In the Avesta, the three sons of Zarathustra are assigned the roles of the progenitors of the three social classes, with the eldest son being the head priest, the second son being an agriculturist, and the third son being a warrior.[157]

In another passage of the Avesta where Zarathustra appears in relation to the three social classes, Zarathustra bestows upon Vištāspa the blessing that he would have ten sons, of whom three would be priests, three would be warriors, and three would be farmer-agriculturists, and one who would be like Vištāspa himself.[158]

The concept of the king encompassing and transcending the social classes is present in the Zoroastrian tradition, with the Vištāsp Yašt and the Āfrīn-i Payğāmbar Zarduxšt of the Avesta explicitly propounding this notion of kingship, which was reiterated by the 9th century AD Zoroastrian scholar Zādspram in his writings.[87]

The blessing bestowed by Zarathustra to Vištāspa, according to which Vištāspa would have ten sons, of whom three would be priests, three would be warriors, three would be farmers, and the tenth would be like Vištāspa, was derived from the Iranic notion of the three sons as the progenitor of the three social classes, while the tenth son who was to be like Vištāspa represented the king within whom the functions of these three social classes were united.[87]

Paralleled the role of the belt with a cup attached to it in establishing Skythēs's role as the supreme priest, Zarathustra was believed to have first established the practise wearing of the kustīg belt which adherents of Zoroastrianism had to start wearing from a young age.[159]

Haošiiaŋha and his heirs

The name Paralatai was a Greek reflection of the Scythian name Paralāta, which was a cognate of the Avestan title Paraδāta (𐬞𐬀𐬭𐬀𐬜𐬁𐬙𐬀), which means "first created."[61][50] In the Avesta, Haošiiaŋha was the first king and the ancestor of the warrior class, that is of the military aristocracy of which the kings were members, and the title Paralāta was assigned in Zoroastrian literature to the first king, Haošiiaŋha, and to his descendants and successors, the Pishdadian dynasty.[1][157]

In Avestan mythology, Haošiiaŋha Paraδāta held the role of the warrior-king who fought against non-Iranic "barbarians" and had both human and demonic enemies, and also laid the foundations of royal power and of sovereignty.[160]

Haošiiaŋha's son Taxma Urupi, who also bore the title of Paraδāta, meanwhile corresponded to the priest-king, being opposed to the same enemies of Haošiiaŋha as well as to sorcerers, and he managed to use magic to turn Aŋra Mainiiu into his horse which he rode for thirty years. Taxma Urupi in Avestan mythology also curbed idolatry and promoted the worship of Ahura Mazdā, and was also credited with inventing writing, which were all attributes of a priest-king, thus making him the equivalent of Lipoxšaya.[160]

Taxma Urupi's successor to the kingship, Yima, meanwhile held the role of a "prosperous king," which corresponded to R̥buxšaya's role as the progenitor of the farmer class. Taxma Urupi's creation of the underground enclosure, the vara, connected him to the lower world, which also signalled his association with the role of the progenitor of the farmer class.[161] Yima's epithet of xšaēta (𐬑𐬱𐬀𐬉𐬙𐬀), meaning "brilliant" and "shining" was a sign of his proximity to the Sun and the Moon due to his possession of the xᵛarᵊnah in his capacity of being king.[79]

A myth similar to that of the golden objects falling from the sky was also present in the Avesta, where Ahura Mazdā offered to Yima a suβrā (either a pick or a shepherd's flute) and an aštrā (a cattle goad), both made of gold, which Yima used on the earth to increase the size of its part which was inhabitable.[17]

The role of R̥buxšaya as the progenitor of the farmer class finds another parallel in the Zoroastrian tradition, where Haošiiaŋha's brother Vaēgerēδ was the creator of agriculture and the ancestor of the farmer class.[1][161][162]

Θrita

In the Hōm Yašt of the Avesta, the hero Θrita was the third mortal man to have prepared the sacred haoma drink. Θrita in turn had two sons, of whom Urvāxšaya was a religious mentor as well as a judge and a lawgiver, while Kərəsāspa was a famous heroic warrior who slew a horned dragon.[162]

The xᵛarᵊnah

The xᵛarᵊnah and kingship

Ahura Mazdā offered to Yima the suβrā and aštrā which Yima used on the earth to increase the inhabitable part of the Earth in the Vendīdād, and Yima used his xᵛarᵊnah to perform this task the Dēnkard, thus identifying the xᵛarᵊnah with the suβrā and aštrā. This story paralleled the acquisition of the hestiai of Tāpayantī by Kolaxšaya, who thus became the possessor of the fārnā and of its physical symbols.[81]

The xᵛarᵊnah was believed to follow the legitimate king and escape from usurpers, but it was also believed to leave the legitimate king and pass over to a better candidate should he become unjust and violate the laws. Thus, in the Avesta, when Yima started to believe lies, his xᵛarᵊnah left him three times in three parts: one part took on the form of the Vārᵊγna bird to pass onto the god Mithra, one part passed onto the prince Θraētaona, who became king, and the third part passed onto Θrita's son, the hero Kərəsāspa, who became a dragon-slaying hero just as Θraētaona had previously been, as a result of which Yima lost the kingship and was succeeded by Θraētaona.[163][164]

The narrative of the xᵛarᵊnah leaving the legitimate king after corruption is present in the Dēnkard, where the king Kāy Us lost his xᵛarᵊnah after attempting to conquer the heavens.[165]

In the Greater Bundahišn, Nōtargā attempted to steal the xᵛarᵊnah of Frētōn by using witchcraft to place it inside a cow whose milk he gave to his three sons to drink. The xᵛarᵊnah rejected each of the sons, and instead passed into one of Nōtargā's daughters, who later gave birth to Kay Apīveh, who possessed the xᵛarᵊnah from birth and became the second Kayanian king and the true founder of the Kayanian dynasty, after which his xᵛarᵊnah passed on to his heirs. Although this myth is not directly connected to the Scythian genealogical myth, this narrative of the xᵛarᵊnah choosing its possessor is nevertheless similar to how the hestiai of Tāpayantī rejected Lipoxšaya and R̥buxšaya, and instead chose Kolaxšaya to become their possessor.[166]

The xᵛarᵊnah and the social classes

Like among the Scythians, the xᵛarᵊnah in Zoroastrianism was also tripartite,[82] which is reflected in a myth recorded by Zādspram, according to which humans at the time of Hōšang (Haošiiaŋha) - although the Bundahišn sets the story during the time of Taxmurup (Taxma Urupi) - were able to travel from one region of the earth to another on the back of the gigantic bull Srisōk. However, the sacred fire on the back of Srisōk fell into the sea and separated into three Zoroastrian Sacred Fires which possessed the xᵛarᵊnah and were established at three sites. These Three Fires were:[167]

- Ādur Farnbāg, which was dedicated to the priestly class;

- Ādur Gušnasp, which was dedicated to the warrior class;

- Ādur Burzēn-Mihr, which was dedicated to the farmer class.

Unlike the Scythian fārnā, the three components of the xᵛarᵊnah of the Sasanian period were kept separately due to a later Zoroastrian eschatological notion recorded in the Dēnkard, according to which the union of the Fire of the Priests and the Fire of the Warriors was capable of destroying evil, preserve creation, and the renewal of existence. Therefore, since evil still existed in the world, the reunification had to happen in the end times.[82]

Although the Three Fires were located in physically separate spots, they were nevertheless all present within the same kingdom ruled by the same king, due to which the Sasanian kings possessed all three components of the xᵛarᵊnah.[168]

Although Yima is depicted in later Zoroastrian literature as possessing only two physical manifestations of the xᵛarᵊnah, the suβrā and aštrā, in the Bundahišn, he used three fires to perform all his tasks during his reign, with these fires corresponding to the royal xᵛarᵊnah[164] and to the three Scythian hestiai possessed by Kolaxšaya.[169] The reference to the "three fires" suggests that in the earlier variants of the myth, Yima was a perfect king who owned an object representing the priestly function in addition to the suβrā and aštrā, thus possessing the sacred objects which represented the three aspects of kingship and the three social classes, thus corresponding exactly to the three objects which were in the possession of Kolaxšaya in the Scythian genealogical myth.[170]

The discrepancy between Yima possessing three sacred objects in the earlier form of the myth and only two in the later variant is due to a later Zoroastrian development, recorded in the narrative from the Vendīdād, where Ahura Mazdā initially offered to Yima to study and preserve the Good Religion, which Yima refused. Ahura Mazdā then offered kingship of the whole world to Yima, and he accepted and therefore received the suβrā and aštrā, which are described in the text of the Vendīdād as the xšaθra, meaning "royal powers," and which respectively represent the farmer and warrior functions. Since Yima refused to preserve religion, he did not possess the third physical manifestation of the xᵛarᵊnah representing the priestly class, which was to be owned by Zarathustra,[169] hence why the objects possessed by Yima became reduced to two in later Zoroastrian myth.[170]

These differences resulted from innovations by the priestly class to discredit the claims of the kings of being the divine agents, and which were canonised in the myth of Yima believing the lies.[171] According to this myth, Yima performed faultless sacrifices which ensured that paradical conditions on prevailed on Earth during his thousand-year rule which were marked by perfect climate, the unity of all beings under his rule, the powerlessness of demons, and the absence of death, old age, hunger, and thirst.[172] However, Yima then listened to the lies and claimed that he was the one who had created all the spiritual and material beings, after which he lost divine favour and his xᵛarᵊnah left him, and his perfection and Golden Age ended and were replaced by the present human world where death, disease, wars, demons, lying kings, and propaganda prevailed. This state of trouble could only be ended by the establishment of the Good Religion, which was founded by Zarathustra, who founded priestly institutions, teachings, practices, and texts; unlike othe ancient Iranic traditions which held that the king was the divinely-ordained agent who had to restore the primordial paradise, in the Zoroastrian tradition, kings caused disasters for themselves as well as their people and the world because they would inevitably lie, thus making kings themselves the responsibles for the end of this paradisal state.[173]

Therefore, Yima's kingship in later Zoroastrian literature was incomplete, since he united within himself the warrior and farmer functions, but not the priestly one, hence why Yima is described in Zoroastrian literature as possessing the full royal xᵛarᵊnah but none of the religious xᵛarᵊnah, while Zarathustra possessed the full religious xᵛarᵊnah but none of the royal xᵛarᵊnah.[169]

However, in some myths relating to Yima, he possessed a belt, which was a symbol of the priestly class, and Yima's belt was even said to be identical to the Zoroastrian religion in some texts, thus allowing him to use the belt to render Ahriman (the Avestan Aŋra Mainiiu) and his demons powerless. This paralleled the role of the belt with a cup attached to it in establishing Skythēs's role as the supreme priest.[159]

According to the Dēnkard, Yima's xᵛarᵊnah passed on to:[164]

- Frētōn (the Avestan Θraētaona), who received the farmers' part of the xᵛarᵊnah;

- Sāmān Karsāsp (the Avestan Kərəsāspa), who received the warriors' part of the xᵛarᵊnah;

- Ošnar, a sage who received the priests' part of the xᵛarᵊnah.

In the Yašt 19 of the Avesta, Ahura Mazdā told Zarathustra that whoever would be able to capture the xᵛarᵊnah that once belonged to Yima, which was hidden in the Vourukaša ocean, would obtain three boons, consisting of the boon of the priests, the boon of well-being and wealth, and the boon of victory with which he would be able to destroy all enemies. These three parts were reunited in the xᵛarᵊnah of the kings of the Kayanian dynasty.[164]

In both the Dēnkard's and the Yašt 19's narratives, the three parts of Yima's xᵛarᵊnah are listed in the same order as the sons of Targī̆tavah, with the first part corresponding to the priests, the second part to the farmers, and the third part to the warriors.[164]

The Ayādgār-ī Jāmāspīg

In the Zoroastrian eschatological text, the Ayādgār-ī Jāmāspīg, the hero Ferēdūn had three sons, who each represented the social classes, were also the ancestors of the three major populations of the known world:[174]

- the eldest, Salm, was the ancestor of the producer class, and became the ruler of Rome;

- the second, Tōz, was the ancestor of the warrior-aristocracy, and became the ruler of Turkestan and the desert;

- the third, Ēriz, was the ancestor of the priesthood, and became the ruler of Iran and India.

This variant of the myth had, however, undergone some modifications proper to Zoroastrianism, so that the dominant class descended from the youngest son of Ferēdūn was that of the priests rather than the warrior aristocracy. Some aspects of the original version of the myth were nevertheless still present, so that Ferēdūn still gave to Ēriz the xᵛarᵊnah, which was normally an attribute of the kings and of the warrior aristocracy; and the power of Ēriz it itself described in the Ayādgār-ī Jāmāspīg as consisting of xvatāyīh u pātexšāhīh, that is of royalty and rulership. In the Dēnkard, Ēriz instead received from his father the vāxš (𐬬𐬁𐬑𐬱), that is speech, due to the replacement of the original royal attributes of Ēriz by priestly ones.[174]

The roles of the sons of Ferēdūn as the ancestors of three peoples parallel the second version of the Scythian genealogical myth recorded by Herodotus of Halicarnassus, where the sons of "Hēraklēs" each became the ancestors of a Scythic tribe.[174]

The sons of Mihr-Narseh

In the 5th century AD, the Sasanid wuzurg framadār Mihr-Narseh had his three sons appointed to important positions at the head of the three estates of Persian society:[175]

- the eldest son was named the hērbadān hērbad, which was the second highest position within the clerical hierarchy;

- the second son was appointed as the vāstryōšān-sālār, that is the head of the agriculturists, who was also the minister in charge of taxation and finance;

- the third son became the artēštārān-sālār, that is the head of the warriors, and the grand marshal.

The order of the respective professions of the sons of Mihr-Narseh corresponded to the functions of the sons of both Zarathustra and Targī̆tavah, and Mihr-Narseh might have intentionally chosen this order of professions to emulate Zoroaster himself or one of the ancient pious kings of Zoroastrian mythology.[175]

Mihr-Narseh also built four fire temples near his home town, with one being for himself and corresponding to the king's personal fire, which was also the prime fire of the empire, and the other three corresponding to each of his sons and which also corresponded to the three Great Fires of the Sasanid Empire.[175]

The primordial unity

The theme of the primordial unity of creation was also present in the Zoroastrian cosmogenetic myth, where Ahura Mazdā created the Sky, Water, Earth, Plant, Animal, and Human. The first Plant, Animal, and Human each included within their bodies all of the good qualities which were present in the various plants, animals, and humans who later came into existence, so that this state of primordial perfection was characterised by integrity of body and spirit, due to which these original beings were free of vice, disease, suffering and death.[176]

This primordial perfection was lost when Aŋra Mainiiu attacked the creations of Ahura Mazdā and killed the primordial plant, the primordial animal, and the primordial human in this specific order. However, the death of these primordial beings was not their end, and they instead fragmented into smaller parts which then became the many types of plants, animals, and humans, all of which contained both some good and some evil, and the ability to reproduce, which was itself the replacement of immortality by the perpetuation of the species. Thus, the original perfection was replaced by a combination of good and evil, and the shattered primordial unity became a multiplicity, with these changes creating the possibility for the arising of confusion and conflict.[177]