Civic Center, San Francisco

Civic Center UN Plaza | |

|---|---|

| San Francisco Civic Center Historic District | |

Aerial view of Civic Center at dusk in 2016, facing north. San Francisco City Hall is featured in the center. | |

| Coordinates: 37°46′45″N 122°24′57″W / 37.77917°N 122.41583°W | |

| Government | |

| • Supervisor | Jane Kim and London Breed ( block bounded by Van Ness, Turk, Golden Gate Ave., & Franklin ). |

| • State Assembly | Matt Haney (D)[1] |

| • State Senator | Scott Wiener (D)[1] |

| • U. S. Rep. | Nancy Pelosi (D)[2] |

| Area | |

• Total | 1.27 km2 (0.492 sq mi) |

| • Land | 1.27 km2 (0.492 sq mi) |

| Population (2008) | |

• Total | 10,101 |

| • Density | 7,925/km2 (20,525/sq mi) |

| [3] | |

| ZIP codes | 94102, 94109 |

| Area codes | 415/628 |

| [3] | |

San Francisco Civic Center Historic District | |

San Francisco Civic Center, looking west along UN Plaza to City Hall | |

| Location | Roughly bounded by Golden Gate Ave., 7th, Franklin, Hayes, and Market Sts., San Francisco, California |

| Area | 45.6 acres (18.5 ha) |

| Built | 1912[5] |

| Architectural style | Late 19th and 20th Century revivals Beaux-Arts |

| NRHP reference No. | 78000757[4] |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | October 10, 1978[4] |

| Designated NHLD | February 27, 1987[6] |

The Civic Center in San Francisco, California, is an area located a few blocks north of the intersection of Market Street and Van Ness Avenue that contains many of the city's largest government and cultural institutions. It has two large plazas (Civic Center Plaza and United Nations Plaza) and a number of buildings in classical architectural style. The Bill Graham Civic Auditorium (formerly the Exposition Auditorium),[5] the United Nations Charter was signed in the Veterans Building's Herbst Theatre in 1945, leading to the creation of the United Nations. It is also where the 1951 Treaty of San Francisco (the peace treaty that officially ended the Pacific War with the Empire of Japan, which had surrendered in 1945) was signed. The San Francisco Civic Center was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1987[6] and listed in the National Register of Historic Places on October 10, 1978.[4]

Location

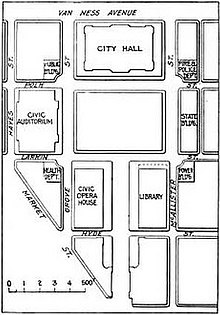

The Civic Center is bounded by Market Street to the southeast, Franklin Street to the west, Turk Street to the north, and Leavenworth Street, McAllister Street, and Charles J. Brenham Place to the east. The Civic Center borders the Tenderloin neighborhood on the north and east and the Hayes Valley neighborhood on the west; Market Street separates it from the South of Market, or "SoMa", neighborhood.

History

The first permanent San Francisco City Hall was completed in 1898 on a triangular-shaped plot in what later became Civic Center, bounded by Larkin, McAllister, and Market, after a protracted construction effort that had started in 1871; although the constructors had promised to complete work within two years, "honest graft" was an accepted practice, and the cost of the structure ballooned from $1 million as budgeted to $8 million.[7]: 170

The Civic Center was built in the early 20th century after the earlier City Hall was destroyed in the 1906 earthquake and fire. Although the architect and urban planner Daniel Burnham had provided the city with plans for a neo-classical Civic Center shortly before the 1906 earthquake,[8] his plans were never carried out. Burnham's plan called for a large semi-circular plaza at the intersection of Market and Van Ness as a hub linking official buildings along spoked streets.[9]: 10–11

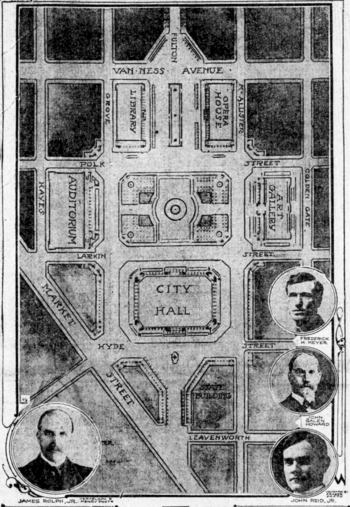

Following the earthquake, a temporary city hall was established on Market Street, but planning for a permanent structure and civic center did not take place for several years. The current Civic Center was planned by a group of local architects, chaired by John Galen Howard.[7] The new Civic Center would consist of five main buildings facing a central rectangular plaza: City Hall, Auditorium, Main Library, Opera House, and State Office Building.[9]: 12 A bond was issued on March 29, 1912, for $8.8 million to carry out the construction of the new Civic Center; at the time, the city only owned the triangular-shaped plot where the old City Hall had stood prior to the earthquake.[10] A resolution passed by the San Francisco Board of Supervisors required the new City Hall to be built on the site of the old City Hall, so early plans for Civic Center showed City Hall east of the central plaza. Opinions solicited by the consulting architectural team led to the relocation of City Hall to the west side of the plaza.[9]: 12 Ground was broken for City Hall, the first building in the new Civic Center, on April 5, 1913.[11][10]

The current City Hall was completed in 1915, in time for the Panama–Pacific International Exposition. The second building to be started was Exposition Auditorium; at the time, plans included a new Main Library (to be built on the site of the old City Hall) but left the former Marshall Square (bounded by Larkin, Fulton, Hyde, and Grove) undeveloped.[10] Plans for a new opera house on Marshall Square had been dropped[10] The Main Library (1916), the California State Building (1926), War Memorial Opera House and its neighboring twin, the War Memorial Veterans Building (which together were the nucleus of the San Francisco War Memorial and Performing Arts Center, completed in 1932), and the Old Federal Building (1936) were all completed after the Exposition. Civic Center Plaza was established by 1915, but not completed until 1925. Marshall Square remained undeveloped[9]: 12, 14 until the new Main Library was constructed there in the early 1990s.

During World War II, Army barracks and Victory gardens were constructed in Civic Center Plaza, which lies directly east of City Hall and west of the Library. The 1950s through the 1970s and 1980s saw tall post-modernist Federal and State buildings constructed in the area; an underground exhibition facility, Brooks Hall, was completed beneath the plaza in 1958, followed by an adjoining garage in 1960. The Louise M. Davies Symphony Hall and Harold L. Zellerbach Rehearsal Hall were added in 1980. The 1990s saw the construction of a new Main Library on the unoccupied Marshall Square block, and the old Main Library building was converted into the Asian Art Museum, and the removal of all public benches. In 1998, the city officially renamed part of the plaza the Joseph L. Alioto Performing Arts Piazza after the former mayor.

Its central location, vast open space, and the collection of government buildings have made and continue to make Civic Center the scene of massive political rallies. It has been the scene of massive anti-war protests and rallies since the Korean War. It was also the scene of major moments of the Gay Rights Movement. Activist Harvey Milk held rallies and gave speeches there. After his assassination on November 27, 1978, a massive candlelight vigil was held there. Later, it was the scene of the White Night Riots in response to the lenient sentencing of Dan White, Milk's assassin. Recently, Civic Center was the center point of same-sex marriage activism, as Mayor Gavin Newsom married couples there.

Attractions and characteristics

- Government

- Monuments

- Culture

- Parks and open spaces

- Transit stops

- Education

Government center

The centerpiece of the Civic Center is the City Hall, which heads the complex and takes up two city blocks on Polk Street. The section of the street in front of the building was renamed for Dr. Carlton B. Goodlett, a local African American activist. Across the street on McAllister Street is the headquarters of the Supreme Court of California. Across from that building is the Asian Art Museum, opened in 2004 in the former main branch building of the San Francisco Public Library, which moved to a newer building constructed just south of Fulton in 1995.

North of City Hall is the Phillip Burton Federal Building and United States Courthouse for the United States District Court for the Northern District of California, and State of California office buildings. This includes offices of several federal agencies, including the Federal Bureau of Investigation San Francisco Field Office.[12] East of the main Civic Center complex on nearby Mission Street, is the head courthouse of the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit which sits across 7th from the San Francisco Federal Building complex.

Monuments

The Pioneer Monument, funded by the estate of James Lick and dedicated to Manifest Destiny, is located in the middle of Fulton Street between the Library and the Asian Art Museum. The section of Fulton Street between Hyde and Leavenworth streets was pedestrianized and re-developed into United Nations Plaza in 1975 as a monument for the United Nations and the signing of the UN Charter, when the Bay Area Rapid Transit subway was constructed under Market Street. The 2.6-acre (11,000 m2) pedestrian mall was designed by Lawrence Halprin.[13] It was rededicated in June 1995 by visiting members of the UN General Assembly as part of its 50th anniversary, and renovated and rededicated again in 2005 during the World Environment Day event. Currently, it is the site of a small farmers' market as well as a replica of a large equestrian statue of Simon Bolivar.

Culture

West of City Hall on Van Ness Avenue is the War Memorial Opera House, where the U.N. Charter was signed in 1945 and the Treaty of San Francisco was signed in 1951. Davies Symphony Hall is south of the Opera House; to its north is the War Memorial Veterans Building, which contains the Herbst Theatre. The Bill Graham Civic Auditorium and SHN Orpheum Theatre are also located in Civic Center.

Parks and open spaces

The main open space just east of City Hall is Civic Center Plaza. Despite the area's seedy reputation due to its proximity to the Tenderloin, its central location also makes it the center of many of the city's festivals and parades. Many street parades and parties are held in Civic Center Plaza, including San Francisco's Gay Pride Parade, the city's Earth Day celebration (which attracts 15,000+ people), the St. Patrick's Day parade, San Francisco's version of the Love Parade, and the San Francisco LovEvolution party.

Renovated and re-opened on February 15, 2018, the Helen Diller Civic Center Playgrounds reside on the northeast and southeast corners of the Civic Center Plaza.[14] The San Francisco Parks and Recreation program partnered with The Trust for Public Land to renovate the 20 year old playgrounds.[15] The playgrounds were funded by a generous $10 million donation from the Helen Diller Family Foundation.[14][15][16] The playgrounds serve many surrounding neighborhoods with limited open space such as the Tenderloin, Western Addition, Hayes Valley, and South of Market neighborhoods.[15]

Transit

Access to Civic Center is provided by the Civic Center Station on Market, a subway stop for both BART and the Muni Metro. The F Market historic streetcar line and many Muni bus lines also run nearby.

Education

Civic Center is the site of four famous higher education schools: Minerva Schools at KGI, the University of California, Hastings College of the Law, the private The Art Institute of California – San Francisco and The San Francisco Conservatory of Music. UC Hastings is located on the two blocks straddling Hyde between Golden Gate and McAllister. Academy of Art University owns two buildings in the neighborhood, and the buildings are used primarily for academic and administrative purposes.[17]

Other points of interest

The Fox Plaza condominium complex is also located nearby. The large art installation Firefly by Ned Kahn can be seen on the side of the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission building on Golden Gate Avenue.

In December 2010, a set of innovative wind and solar hybrid streetlamps provided by Urban Green Energy were installed[18] as part of the center's vision for sustainability.

Selected photos

- Ronald M. George State Office Complex: Earl Warren Building with the Hiram W. Johnson State Office Building behind

See also

References

- ^ a b "Statewide Database". UC Regents. Archived from the original on February 1, 2015. Retrieved December 8, 2014.

- ^ "California's 11th Congressional District - Representatives & District Map". Civic Impulse, LLC.

- ^ a b c "Civic Center neighborhood in San Francisco, California (CA), 94102, 94109 subdivision profile - real estate, apartments, condos, homes, community, population, jobs, income, streets".

- ^ a b c "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- ^ a b Charleton, James P. (November 9, 1984). "San Francisco Civic Center" (pdf). National Register of Historic Places – Inventory Nomination Form. National Park Service. Retrieved May 20, 2012.

- ^ a b "San Francisco Civic Center". National Historic Landmark Quicklinks. National Park Service. Archived from the original on October 8, 2012. Retrieved March 20, 2012.

- ^ a b Issel, William; Cherny, Robert (1986). San Francisco 1865–1932: Politics, Power, and Urban Development. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. pp. 170–171. ISBN 0-520-05263-3. Retrieved October 26, 2018.

- ^ Burnham, Daniel H.; Bennett, Edward H. (September 1905). O'Day, Edward F. (ed.). Report on a plan for San Francisco (Report). Association for the Improvement and Adornment of San Francisco. Retrieved January 31, 2017.

- ^ a b c d Civic Center Proposal (PDF) (Report). City and County of San Francisco, Office of Mayor Dianne Feinstein. November 1987. Retrieved October 26, 2018.

- ^ a b c d "Civic Center at San Francisco". Engineering Record: 489. October 31, 1914. Retrieved October 26, 2018.

- ^ "Now for New City Hall". San Francisco Call. April 5, 1913. Retrieved October 26, 2018.

- ^ "San Francisco Division." Federal Bureau of Investigation. Retrieved on June 9, 2015. "450 Golden Gate Avenue, 13th Floor San Francisco, CA 94102-9523"

- ^ 2.6 acres, 1975, part of BART construction, Halprin as designer Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b "$10 million playgrounds give downtown SF kids a safe place to frolic". SFChronicle.com. February 16, 2018. Retrieved August 1, 2018.

- ^ a b c "Helen Diller Playgrounds at Civic Center Improvements | San Francisco Recreation and Park". sfrecpark.org. Retrieved August 1, 2018.

- ^ "Helen Diller Civic Center Playgrounds". The Trust for Public Land. Retrieved August 1, 2018.

- ^ "Academy of Art University Campus Map" (PDF). academyart.edu. Academy of Art University. Retrieved November 23, 2016.

- ^ Hybrid Street Lamp Hits San Francisco Archived 2010-12-20 at the Wayback Machine

External links

- Photo tour of Civic Center A photo tour of Civic Center complete with narrative text.

- "San Francisco Civic Center" (pdf). Photographs. National Park Service. Retrieved May 20, 2012.

- The architects

- Earth Day SF San Francisco's very well attended Earth Day celebration.

- "City Hall and Civic Center History". San Francisco Municipal Reports. San Francisco Board of Supervisors: 977–1014. 1918. Retrieved October 26, 2018.