Royal Theatre Toone

Royal Theatre Toone | |

| |

| Address | Rue du Marché aux Herbes / Grasmarkt 66 1000 City of Brussels, Brussels-Capital Region Belgium |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 50°50′50″N 4°21′12″E / 50.84722°N 4.35333°E |

| Public transit | Brussels-Central |

| Type | Puppet theatre |

| Opened | 1830 |

| Website | |

| Official website | |

The Royal Theatre Toone (French: Théâtre royal de Toone; Dutch: Koninklijk Poppentheater Toone), often simply referred to as Toone, is a folkloric theatre of rod marionettes in central Brussels, Belgium, active since 1830, and the only traditional Brussels puppet theatre still in operation.[1]

Originally founded by Antoine "Toone" Genty in the Marolles/Marollen district of Brussels, since 1966, the theatre has been located at the end of two narrow alleyways, at 66, rue du Marché aux Herbes/Grasmarkt, near the Grand-Place/Grote Markt (Brussels' main square).[2] The theatre's premises also house a tavern and a small puppetry museum.[1] The current director is Nicolas Géal, also known as Toone VIII.[3]

The theatre still puts on puppet plays in the Brusselian dialect (also sometimes referred to as Marols or Marollien), the traditional Brabantian dialect of Brussels.[4] Performances are also given in other languages interspersed with Brusselian, always in the spirit of zwanze, a sarcastic form of folk humour considered typical of Brussels.[5][6]

History

Early history

Around 1830, Antoine "Toone" Genty (1804–1890) opened his poechenellenkelder (literally "puppet cellar"), a traditional theatre of marionettes in the Marolles/Marollen district of Brussels.[2][3] The origin of Brussels' puppetry stems three centuries earlier from an order issued by Philip II of Spain, son of Charles V, who, hated by the population, had the city's theatres closed to prevent them from becoming gathering places likely to encourage hostility towards the Spanish authorities. The people of Brussels had then replaced the actors with poechenelles ("puppets") in underground theatres.[7][1][8]

At the start of the 19th century, puppet theatres were one of the most successful forms of entertainment for adults in Brussels' working class neighbourhoods. They allowed for great freedom of tone, using a varied repertoire borrowed from popular legends, tales of chivalry, operas, and even religious or historical pieces, broken down into acts and interpreted very freely. They were also a means of popular education. Indeed, illiterate people could not afford the opera or the big theatres. The puppet shows thus allowed them to keep abreast of cultural events. This popular form of entertainment still exists and has evolved today into the Royal Theatre Toone.[1][8]

20th century

Since the 1930s, renowned Belgian artists, writers and patrons have taken part in the defence of this heritage, among them the avant-garde dramatist Michel de Ghelderode (1898–1962), who also wrote plays for the theatre. Later on, some of his other works were adapted to theatre plays by the current owners: José Géal (also known as Toone VII), and his son Nicolas (also known as Toone VIII). Other personalities who supported the theatre and its creations in their lifetimes include the sculptor and jeweller Marcel Wolfers (1886–1976), as well as the painters Jef Bourgeois (1896–1986) and Serge Creuz (1924–1996).[8]

The Royal Theatre Toone was relocated in 1963 by José Géal (or Toone VII) to its current premises, a building dating from 1696 on the Rue du Marché aux Herbes/Grasmarkt, near the Grand-Place in central Brussels.[9][8] The building that now houses the theatre and the alleyway where it is located were designated as a protected ensemble on 27 February 1997.[10]

21st century

Until 2018, the permanent museum of Toone was located on the first floor of the main building, and could be visited free of charge during performance times. As part of extension works, three houses adjacent to the historic building were acquired and fully renovated thanks to a contribution of €1.3 million from Beliris. The main goal of these works, which lasted two years, was to improve accessibility and comfort for visitors, artists and suppliers, as well as to allow access to the museum outside performance times.[11]

An application is underway to grant the theatre's marionettes the status of Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO, a status already enjoyed by some eminent fellow puppeteers of popular tradition.[12] On 11 April 2024, Toone was bestowed with the European Heritage Label in recognition of its cultural significance and historical importance.[13]

Ownership

Since the theatre's humble foundation in the Marolles in 1830, and during its chequered history, nine showmen have succeeded one another in the Toone dynasty. The transition is not necessarily from father to son, nor even within the same family, but is often passed on by apprenticeship with the approval of the audience, the narrator being "enthroned" by the previous owner.[8] After Genty, the name Toone (Brussels' diminutive of Antoine) has been adopted by all of the theatre's unrelated (except two) successive owners.[2][3] In 2003, the eighth "generation", Toone VIII, took office.[14]

Historical owners

- Toone I, known as Toone the Elder (French: Toone l'Ancien): Antoine Genty (1804–1890), marollien, car painter by day and puppeteer by night. He could neither read nor write and made his own puppets. He cared little for historical truth and recounted popular legends, medieval epics and religiously inspired plays to a loyal audience, during his 45-year career.[3]

- Toone II, known as Jan van de Marmit: François Taelemans (1848–1895), marollien, painter and friend of Toone I. He apprenticed as a puppeteer alongside Toone the Elder and succeeded him whilst keeping up the tradition. He had to change "puppet cellars" several times for hygiene and safety reasons.[3]

- Toone III: after Toone II’s death, a turbulent period followed. Toone’s reputation was envied and around fifteen competing theatres attempted to appropriate the name. Two serious contenders claimed the title:

- Toone III, known as Toone de Locrel: Georges Hembauf (1866–1898), marollien, workman. Trained by Toone II, he gave his theatre a new dimension by adding a new repertoire, sets and puppets, which allowed him to keep his audience despite the competition. His son was named Toone IV, the first hereditary succession.[3]

- Toone III, known as Jan de Crol: Jean-Antoine Schoonenburg (1852–1926), marollien, hatter. Initiated by Toone the Elder, he resorted to a more advanced method of playwriting: he read novels, took notes, developed a canvas, and improvised the dialogues in front of his audience. His performances could sometimes last two months, with the same regulars turning up every evening to watch the show. Forced to abandon the profession, which had become unprofitable, he ceded his theatre to Daniel Vanlandewijck, future Toone V, and hanged himself among his puppets.[15][3]

- Toone IV: Jean-Baptiste Hembauf (1884–1966), marollien, son of Toone de Locrel. Associated with the puppet maker Antoine Taelemans (son of Toone II), he ran his theatre for 30 years. However, with the outbreak of World War I and the advent of cinema, Toone IV was forced to close the doors of his theatre. The Amis de la marionnette ("Friends of the puppet"), a group of patrons, safeguarded the Brussels puppets and allowed Toone IV to resume his activities. He staged Le mystère de la Passion, a play written by Michel de Ghelderode based on oral tradition.[3]

- Toone V: Daniel Vanlandewijck (1888–1938), factory worker. He bought Jan de Crol's practice. Victim of an audience crisis and increasing hygiene requirements, he gave up the profession and sold his puppets. Bought by the Amis de la marionnette, the heritage was fortunately preserved.[3]

- Toone VI: Pierre Welleman (1892–1974), workman. First associated with Toone V, he then succeeded him with his four sons. During World War II, a bomb fell next to his workshop and destroyed 75 puppets. Moreover, television and football represented new competitors. Struck with expropriation, Toone VI, discouraged, began selling his puppets.[3]

Current owners

- Toone VII: José Géal (1931–), comedian, he discovered the Toone Theatre and founded his own company. When Toone VI stopped performing in 1963, exhausted by the difficulties encountered in safeguarding this folklore, José Géal officially replaced him as Toone VII. As he could not find an ideal location to set up his theatre in the Marolles, he moved to the current building, a stone's throw away from the Grand-Place. In 1971, the City of Brussels bought this building to help Géal keep his puppets alive.[8] Far from looking towards the past, Toone VII opened up the Royal Theatre Toone to Europe and to the world by updating the repertoire and translating his shows into English, but also into Spanish, Italian and German (always interspersed with the Brusselian dialect), thereby attracting new audiences. Tourists, students, the regulars and the curious are now replacing the marollien spectators.[2][3] He was made Officer of the Order of Leopold in 2004.[16]

- Toone VIII: Nicolas Géal (1980–), comedian, son of Toone VII, he was crowned Toone VIII on 10 December 2003 at Brussels' Town Hall, under the aegis of the then-mayor of Brussels, Freddy Thielemans.[3] His first creation in 2006 was a Romeo and Juliet based on William Shakespeare.

Practical information

Location and accessibility

The theatre is located north of the Grand-Place, at the end of two narrow alleyways known as the Impasse Schuddeveld/Schuddeveldgang and the Impasse Sainte-Pétronille/Sint-Petronillagang (themselves located at, 66, rue du Marché aux Herbes/Grasmarkt).[2] The district, commonly called Îlot Sacré since the 1960s due to its resistance to demolition projects, is located within the perimeter of the Grand-Place and consists of very dense city blocks testifying to the urban organisation of Brussels in the Middle Ages. The old buildings, meanwhile, belong to the so-called "reconstruction" period that followed the bombardment of the city in 1695.[1]

Opening hours

The theatre is open all year round, except in January. At least four shows are organised per week, every Thursday, Friday and Saturday at 8:30 p.m., and on Saturdays also at 4:00 p.m. Shows can be played in short version (+/- 45 minutes) or in full version (+/- 2 hours). The folkloric tavern on the ground floor is open every day from 12:00 to 24:00, except Monday (closing day).[1]

Gallery

- Entrance of the theatre

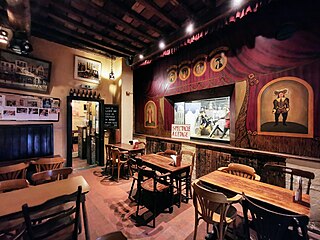

- Theatre room

- Puppet show

- Tavern

- Old Puppets in the museum

- Puppet collection

See also

References

Citations

- ^ a b c d e f "Théâtre Royal de Toone". www.toone.be. Retrieved 13 August 2019.

- ^ a b c d e De Vries 2003, p. 48–49.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Patrimoine vivant Wallonie-Bruxelles - Le Théâtre Royal de Toone". www.patrimoinevivantwalloniebruxelles.be. Retrieved 12 October 2021.

- ^ Evans 2008, p. 71.

- ^ State 2004, p. 356.

- ^ "ZWANZE: Définition de ZWANZE". www.cnrtl.fr (in French). Retrieved 2 February 2018.

- ^ Demol 1963, p. 145–188.

- ^ a b c d e f "Le Théâtre Royal de Toone — Patrimoine - Erfgoed". patrimoine.brussels. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "Théâtre Royal de Toone". www.toone.be. Retrieved 13 August 2019.

- ^ "Bruxelles Pentagone - Théâtre Toone - Impasse Schuddeveld 6 - ROMBAUX Jean". www.irismonument.be. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- ^ "Inauguration de la nouvelle extension du Théâtre de Toone". BX1 (in French). 14 November 2018. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- ^ "La marionnette à tringle et le tapis de fleurs de Bruxelles candidats au patrimoine de l'Unesco". RTBF (in French). Retrieved 16 August 2024.

- ^ "Royal Theatre Toone, Brussels (Belgium) | Culture and Creativity". culture.ec.europa.eu (in Dutch). Retrieved 29 April 2024.

- ^ "Toone". World Encyclopedia of Puppetry Arts. 28 April 2016. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- ^ Longcheval & Honorez 1984, p. 26.

- ^ "STARS Toone VII, Officier de l'Ordre de Léopold". DHnet (in French). 1 November 2024. Retrieved 1 November 2024.

Bibliography

- Evans, Mary Anne (2008). Frommer's Brussels and Bruges Day by Day. First Edition. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-72321-0.

- Demol, Antoine (1963). "Quatre Siècles de Marionnettes Bruxelloises". Le Folklore Brabançon (in French). 158. Brussels.

- De Vries, André (2003). Brussels: A Cultural and Literary History. Oxford: Signal Books. ISBN 978-1-902669-46-5.

- Longcheval, Andrée; Honorez, Luc (1984). Toone et les marionnettes de Bruxelles (in French). Brussels: Paul Legrain.

- State, Paul F. (2004). Historical dictionary of Brussels. Historical dictionaries of cities of the world. Vol. 14. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-5075-0.

External links

Media related to Royal Toone Theatre at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Royal Toone Theatre at Wikimedia Commons