Road racing

Road racing is a North American term to describe motorsport racing held on a paved road surface. The races can be held either on a closed circuit or on a street circuit utilizing temporarily closed public roads. The objective is to complete a predetermined number of circuit laps in the least amount of time, or to accumulate the most circuit laps within a predetermined time period. Originally, road races were held almost entirely on public roads. However, public safety concerns eventually led to most races being held on purpose-built racing circuits.

Road racing's origins were centered in Western Europe and Great Britain as motor vehicles became more common in the early 20th century. After the Second World War, automobile road races were organized into a series called the Formula One world championship sanctioned by the Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile (FIA), while motorcycle road races were organized into the Grand Prix motorcycle racing series and sanctioned by the Fédération Internationale de Motocyclisme (FIM).[1] The success and popularity of road racing has seen the sport spread across the globe with Grand Prix road races having been held on six continents.[2] Other variations of road racing include; open-wheel racing, sports car racing, touring car racing, stock car racing, superbike racing, truck racing, kart racing and endurance racing.

History of road racing

Early road racing

The first organized automobile race was held on July 22, 1894, from Paris to Rouen, France.[1][3][4] The first held in the United States was a 54-mile competition from Chicago to Evanston, Illinois and return, held on November 27, 1895.[1][5] By 1905, the Gordon Bennett Cup, organized by the Automobile Club de France, was considered the most important race in the world.[1][4][6] In 1904, the Association Internationale des Automobiles Clubs Reconnus was formed by several European automobile clubs.[7] In 1904 the FIM created the international cup for motorcycles.[8][9] The first international motorcycle road race took place in 1905 at Dourdan, France.[8][9]

After disagreeing with Bennett Cup organizers over regulations limiting the number of entrants, the French automobile manufacturers responded in 1906 by organizing the first French Grand Prix race held at Le Mans.[6][10] During the 1910s, the Elgin National Road Races held on public roads around Elgin, Illinois attracted competitors from around the country and drew large crowds of spectators.[11][12][13] The first 24 Hours of Le Mans endurance race was held in 1923.[14] The Automobile Racing Club of America was founded in 1933 and became the Sports Car Club of America in 1944.

Race course evolution

The great majority of road races were run over a lengthy circuit of closed public roads, not purpose-built racing circuits.[15] This was true of the Le Mans circuit of the 1906 French Grand Prix, as well as the Targa Florio (run on 93 miles (150 km) of Sicilian roads), the 75 miles (121 km) German Kaiserpreis circuit in the Taunus mountains, the 48 miles (77 km) French circuit at Dieppe, used for the 1907 Grand Prix and, the Isle of Man TT motorcycle road circuit first used in 1907.[16][17][18] The exceptions were the steeply banked egg-shaped near oval circuit of Brooklands in England, completed in 1906, the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, and the oval, banked speedways constructed in Europe at Monza in 1922 and at Montlhéry in 1924.[19][20][21][22]

Road racing on public roads was banned in Great Britain in 1925 when a spectator was injured at the Kop Hill Climb event. The Royal Automobile Club (R.A.C.) and the Auto-Cycle Union (A.C.U.) stopped issuing permits for races on public roads, a policy that has not changed to this day.[15] Donington Park was the first permanent park circuit in the United Kingdom and held its first motorcycle race in 1931.[23] As automobile and motorcycle technology improved, racers began to achieve higher speeds that caused an increasing number of accidents on roads not designed for motorized vehicles.[1][24] Public safety concerns ultimately caused the number of road racing events on public roads in Europe to decrease over the years.[24] Notable exceptions are the Mille Miglia which was allowed to continue until 1957 and, the Pau Grand Prix which has been held on the city streets of Pau, France since 1933.[1][25][26]

After the First World War, automobile and motorcycle road racing competitions in Europe and in North America went in different directions.[1][27] Automobile and motorcycle racing in the United States was typically oval track racing on paved tracks such as the Indianapolis Motor Speedway and the Milwaukee Mile track, or on dirt tracks using widely available horse racing circuits.[1][27] Automobile dirt track racing would develop into stock car racing. American racing also branched out into drag racing.[1]

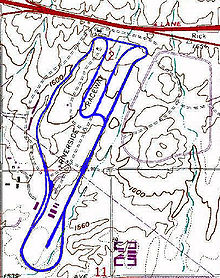

Road racing traditions in Europe, South America, Great Britain and the British Commonwealth nations grew around races held on paved, public roads such as the Circuit de la Sarthe circuit near the town of Le Mans, France, the Spa-Francorchamps Circuit in Belgium and the Mount Panorama Circuit in Australia.[27] Certain European race circuits were situated in mountainous regions where the topography meant that the roads featured numerous curves and elevation changes, allowing the creation of sinuous and undulating race courses such as the Nürburgring in the Eifel mountains of Germany and the Circuit de Charade in the Chaîne des Puys in the Massif Central of France.[28] These circuits presented such a challenge that they were both feared and respected by racers. The 20.8 km (12.9 mi) long Nurburgring with more than 300 metres (1,000 feet) of elevation change from its lowest to highest points, was nicknamed "The Green Hell" by Jackie Stewart, due to its challenging nature.[29] The sinuous track layout of the Charade circuit caused some drivers like Jochen Rindt in the 1969 French Grand Prix to complain of motion sickness, and wear open face helmets just in case.[28]

Post-war era

In 1949 the FIM introduced the Grand Prix motorcycle racing world championship with the 1949 Isle of Man TT being the inaugural event.[17][30] With the exception of the Monza circuit, all the Grand Prix races were held on street circuits. The Association Internationale des Automobiles Clubs Reconnus was renamed the Fédération Internationale de l’Automobile in 1946 and, plans were developed for a road racing world championship. In 1950, the FIA created the Formula One world championship, a competition of seven rounds that included the Indianapolis 500.[31][32] A Formula I manufacturers' championship was begun in 1955.

The success of American racers such as Phil Hill and Dan Gurney in Formula One in the late 1950s sparked to a renewal of interest in road racing in the United States and, led to the construction of new road racing circuits such as Riverside International Raceway, Road America and Laguna Seca.[27] The 1964 United States motorcycle Grand Prix was held at the Daytona International Speedway and led to increased international prominence for the Daytona 200 road race which peaked in 1974 with the victory by 15-time world champion Giacomo Agostini.[27][33]

Racing hazards and safety

The dangers associated with the increasing speeds at road races were highlighted by the 1955 Le Mans disaster.[34] With spectators seated near the edges of the circuit, two race cars came into contact causing one of the vehicles to crash into the embankment, where it exploded in a ball of flames and then plowed through the crowd of spectators.[34] In addition to the driver of the race car, 83 spectators were killed and 120 were injured.[34] Auto racing was temporarily banned in several countries after the Le Mans disaster until safety was improved for spectators.[34] Switzerland would not allow circuit racing until the Zürich ePrix in 2018.[35]

The Formula One championship experienced its worst tragedy during the 1961 Italian Grand Prix at Monza, when driver Wolfgang von Trips lost control of his Ferrari and crashed into a stand full of spectators, killing 15 and himself.[31][36] In 1970, Jochen Rindt won the Formula One drivers' championship posthumously, the only man to do so, underlining the continuing risks associated with road racing.[31] The tragedies highlighted the need for improved safety standards for both drivers and spectators; safety would continue to be an issue throughout the 1960s and 1970s.[31]

When motorcycle racer Gilberto Parlotti was killed while competing in the 1972 Isle of Man TT, it sparked a rider's boycott of the event led by multi-time world champion, Giacomo Agostini, a close friend of Parlotti.[37] Once the most prestigious race of the year, the event was increasingly boycotted by the top riders, and in 1976, the Isle of Man TT finally succumbed to pressure for increased safety in racing events and had its world championship status revoked by the FIM.[37]

Another motorcycle racing incident occurred at Monza during the 1973 Italian motorcycle Grand Prix when a racing accident claimed the lives of world champion Jarno Saarinen and Renzo Pasolini.[38] After the von Trips accident in 1961, the Monza Circuit had been lined with steel barriers as a result of demands by automobile racers. Most auto racers believed steel barriers would improve safety for auto racers and spectators, but they had the opposite effect for motorcyclists and proved fatal for Saarinen and Pasolini.[38][39]

The dangers of street circuits was further exposed at the 1975 Spanish Grand Prix held on the twisty, tree-lined Montjuich circuit in Barcelona.[40] The racing drivers found that the circuit's safety barriers had been shoddily installed and threatened to strike if the barriers were not brought up to standard.[40] Under pressure from race organizers, the race was started only to be stopped after 29 laps when the car of Rolf Stommelen plowed into the crowd, killing four spectators.[40]

Safety improvements

By the late 1970s, the popularity of Grand Prix road racing attracted corporate sponsors and lucrative television contracts which, led to an increased level of professionalism.[31][37] Road racers organized to demand that stricter safety regulations be adopted by sanctioning bodies in relation to race track safety and race organizers requirements.[31][37] Race circuits that had originally been public roads were widened and modified to include chicanes and run-off areas while, some circuits were shortened to reduce the number of safety personnel required. These changes saw a dramatic decrease in deaths and accidents.[41]

Modern road racing on public roads

By the 1980s, motorcycle Grand Prix and the Formula One races were held on purpose built race circuits with the exception of the Monaco Grand Prix held on the city streets of Monaco. Street circuits such as the Montjuïc circuit and the Opatija Circuit with their numerous unmovable roadside obstacles, such as trees, stone walls, lampposts and buildings, were gradually removed from world championship competition.[31][41]

Although events held on closed public roads such as the Isle of Man TT, lost their world championship status due to their considerable safety risk, their popularity continued to flourish leading to a branch of road racing known as Traditional Road Racing.[42] Traditional road racing on closed public roads is popular in the United Kingdom, New Zealand and parts of Europe. The Duke Road Racing Rankings was established in 2002 to establish rider classifications in traditional road racing events such as the North West 200 and the Ulster Grand Prix.

In Formula One, street circuits have made a comeback with the Melbourne Grand Prix Circuit and the Baku City Circuit joining the Circuit de Monaco as part of the world championship. There are no street circuits being used in MotoGP racing.[citation needed]. In North America, racing on public streets takes place at the Grand Prix of Long Beach, the Firestone Grand Prix of St. Petersburg, the Detroit Grand Prix, and the Honda Indy Toronto.

Road racing proliferation

The popularity of Formula One and motorcycle Grand Prix racing led to the formation of road racing world championships for other types of vehicles. In 1953, the FIA sanctioned a world championship for sports car racing which combined the Le Mans 24 Hours, the Mille Miglia, the 12 Hours of Sebring, the 24 Hours of Spa and the 1000km of the Nurburgring.[43] NASCAR held its first road race in 1957 at the Watkins Glen International circuit with Buddy Baker as the winner.[44] The FIA launched the European Touring Car Championship in 1963.[45]

The FIA created the International Karting Commission (CIK) in 1962 and, in 1964, the first CIK Karting World Championship was won by Guido Sala.[46][47] Karting has become a significant step in the development of road racers including Formula One world champion Lewis Hamilton. The European Truck Racing Championship was founded in 1985.[48] A Superbike World Championship for road-going production motorcycles was created in 1988.[49]

As road racing grew in popularity it eventually expanded across the globe with Grand Prix road races having been held on six continents.[50] Expansion of the Formula One and MotoGP series has resulted in many dedicated tracks being built, like in Qatar in the Middle East, Sepang in Malaysia, and Shanghai in China.

See also

- Drag racing

- Formula racing

- Hillclimbing

- Isle of Man TT

- List of Formula One circuits

- List of Grand Prix motorcycle circuits

- Oval track racing

- Street circuit

- Superkart

- Traditional Road Racing

- World Superbike Championship

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Automobile Racing". britannica.com. Retrieved 10 December 2018.

- ^ "The History of Motorcycle Racing". hondaracingcorporation.com. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ^ Rémi Paolozzi (May 28, 2003). "The cradle of motorsport". Welcome to Who? What? Where? When? Why? on the World Wide Web. Forix, Autosport, 8W.

- ^ a b "Dawn of Automobile Racing". grandprixhistory.org. November 2010. Retrieved 17 September 2018.

- ^ "America's First Automobile Race, 1895". eyewitnesstohistory.com. Retrieved September 17, 2018.

- ^ a b "James Gordon Bennett Cup". firstsuperspeedway.com. Retrieved 17 September 2018.

- ^ "About FIA". fia.com. 24 February 2015. Retrieved September 17, 2018.

- ^ a b "Motorcycle Racing". britannica.com. Retrieved 10 December 2018.

- ^ a b "The history about motorcycle racing". rideumba.com. Retrieved September 17, 2018.

- ^ "The First French Grand Prix". firstsuperspeedway.com. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ^ "Elgin Road Races". The Historical Marker Database. Retrieved 25 January 2024.

- ^ "Elgin Road Race" (PDF). elginhistory.org. Retrieved 25 January 2024.

- ^ "The Elgin National Road Race" (PDF). illinois.gov. Retrieved 15 December 2022.

- ^ "Le Mans History". silhouet.com. Retrieved September 17, 2018.

- ^ a b "The Sprint Events of the 1920s". motorsportmagazine.com. Retrieved 27 August 2018.

- ^ "Targa Florio". grandprixhistory.org. 8 August 2008. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ^ a b "History of the Isle of Man TT". iomtt.com. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ^ "History of the Isle of Man TT Races". ttwebsite.com. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ^ "Brooklands History". brooklandsmuseum.com. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ^ "First Indianapolis 500 held". history.com. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ^ "Circuit History". racingcircuits.info. Retrieved 17 September 2018.

- ^ "Montlhéry's motor-racing track". montlhery.com. Retrieved 17 September 2018.

- ^ "Donington Park Trophy". kolumbus.fi. Retrieved 20 September 2018.

- ^ a b "A Short History of Endurance". fim-live.com. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- ^ "Mille Miglia". grandprixhistory.org. November 2007. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ^ "Pau Circuit history". racingcircuits.info. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- ^ a b c d e DeWitt, Norman L. (2010). Grand Prix Motorcycle Racers: The American Heroes. ISBN 9781610600453. Retrieved 19 August 2018.

- ^ a b "The Volcanic Rush of Clermont Ferrand". speedhunters.com. August 2013. Retrieved 25 August 2018.

- ^ "Hidden Glory at the Green Hell". roadandtrack.com. 11 May 2007. Retrieved 25 August 2018.

- ^ "MotoGP History". motogp.com. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g "A Brief History of Formula One". espn.co.uk. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ^ World Championship of Drivers, 1974 FIA Yearbook, Grey section, pages 118 & 119

- ^ Schelzig, Erik. "Daytona 200 celebrates 75th running of once-prestigious race". seattletimes.com. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- ^ a b c d Spurgeon, Brad (11 June 2015). "On Auto Racing's Deadliest Day". The New York Times Company, Inc. Retrieved 19 August 2018.

- ^ "Formula E brings racing back to Switzerland after 60 years". digitaltrends.com. 22 September 2017. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- ^ Collantine, Keith (2011-09-10). "50 years ago today: F1's worst tragedy at Monza". www.f1fanatic.co.uk. Retrieved 2018-08-19.

- ^ a b c d Noyes, Dennis; Scott, Michael (1999), Motocourse: 50 Years Of Moto Grand Prix, Hazleton Publishing Ltd, ISBN 1-874557-83-7

- ^ a b "The darkest day". motorsportmagazine.com. Retrieved 2018-08-20.

- ^ "Monza history". monzanet.it. Archived from the original on 2016-10-11. Retrieved 2017-05-04.

- ^ a b c "Protests in the Park". espn.co.uk. Retrieved 2018-08-20.

- ^ a b "Safety Improvements in Formula One Since 1963". atlasf1.com. Retrieved 20 August 2018.

- ^ "Historical perspective of the Isle of Man TT". cycleworld.com. Retrieved 19 August 2018.

- ^ "History of WEC". wec-magazin.com. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- ^ "Watkins Glen Track History". theglen.com. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- ^ "History of Touring Car Racing 1952-1993". touringcarracing.net. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- ^ "1962". cikfia.com. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- ^ "1964". cikfia.com. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- ^ "European Truck Racing Championship". fia.com. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- ^ "Superbike World Champions". worldsbk.com. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- ^ Davies, Alex. "This Is How You Ship An F1 Car Across The Globe In 36 Hours". Wired. wired.com. Retrieved 20 August 2018.