Richard Sharples

Richard Sharples | |

|---|---|

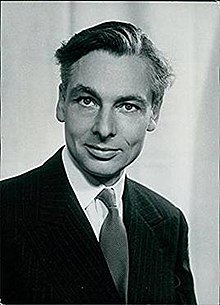

Richard Sharples in 1959 | |

| Governor of Bermuda | |

| In office 1972 – 10 March 1973 | |

| Monarch | Elizabeth II |

| Preceded by | Lord Martonmere |

| Succeeded by | Sir Edwin Leather |

| Member of Parliament for Sutton and Cheam | |

| In office 4 November 1954 – 31 October 1972 | |

| Preceded by | Sydney Marshall |

| Succeeded by | Graham Tope |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 6 August 1916 England |

| Died | 10 March 1973 (aged 56) Hamilton, Bermuda |

| Manner of death | Assassination by gunshot |

| Resting place | St. Peter's Church, St. George's |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 4 |

| Alma mater | Royal Military College, Sandhurst |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1936-1953 |

| Rank | |

| Unit | Welsh Guards |

| Battles/wars | Second World War |

Sir Richard Christopher Sharples, KCMG, OBE, MC (6 August 1916 – 10 March 1973) was a British politician and Governor of Bermuda who was shot dead by assassins linked to a small militant Bermudian Black Power group called the Black Beret Cadre. The former army major, who had been a Cabinet Minister, resigned his seat to take up the position of Governor of Bermuda in late 1972. His murder resulted in the last executions conducted under British rule, in 1977.

Career

Sharples passed out from the Royal Military College, Sandhurst, in 1936 and was commissioned into the Welsh Guards. During the Second World War he served in France and Italy. He rose to the rank of lieutenant colonel and left the army in 1953.[1] He married Pamela Newall in 1946; they had two sons and two daughters. The family greatly enjoyed yachting, and this was the basis of a close friendship with Edward Heath, later prime minister. Sharples was elected Conservative Member of Parliament for Sutton and Cheam in a 1954 by‑election. After the 1970 general election, he served as Minister of State at the Home Office, before resigning his seat in 1972 to take up the position of Governor of Bermuda. He was assassinated in 1973 by a faction associating itself with the Black Power movement.

His widow was subsequently made a life peer as Baroness Sharples.

Death

Sharples was killed outside Bermuda's Government House on 10 March 1973. An informal dinner party for a small group of guests had just concluded, when he decided to go for a walk with his Great Dane, Horsa, and his aide-de-camp, Captain Hugh Sayers of the Welsh Guards. The two men and dog were ambushed and gunned down outside the Governor's residence.[2]

Aftermath

The Governor's coffin was borne by officers of the Bermuda Regiment, and Sayers' by a party from the Welsh Guards. The coffins were carried atop 25-pounder field guns of the Bermuda Regiment, to the Leander-class frigate HMS Sirius, which was stationed at HM Dockyard Bermuda at the time. The ship's Royal Marines detachment provided an honour guard on the flight deck. HMS Sirius conveyed the bodies from Hamilton to St. George's, where they were interred at St. Peter's Church. After the assassination HMS Sirius provided enhanced security for Commodore Cameron Rusby, the Senior Naval Officer West Indies (SNOWI)[3] who was stationed on the island. A detachment of Royal Marines (subsequently replaced by soldiers from the Parachute Regiment) was posted to the Dockyard to guard SNOWI.[4]

Sharples was buried in the graveyard at St Peter's Church in St George's on 16 March 1973, six days after his assassination, with Captain Sayers and Great Dane, Horsa.

Elements of the British Army's airborne forces, which were training at Warwick Camp with the Bermuda Regiment at the time of the murders, were called in to assist the civil authorities. The 23 Parachute Field Ambulance, 1 Parachute Logistic Regiment and the band of the 1st Battalion, The Parachute Regiment subsequently provided protection for government buildings, officials and dignitaries as well as assisting the Bermuda Police.

Manhunt, arrests, and sentence

Police launched a massive manhunt and investigation. Seven months later an armed man named Erskine Durrant "Buck" Burrows was arrested.[5] He confessed to shooting dead Sharples and Sayers. At his trial he was also convicted of murdering the Bermuda Police commissioner George Duckett on 9 September 1972 and killing the co-owner and the bookkeeper of a supermarket in April 1973. He was sentenced to death.[6]

In his confession Burrows wrote:

The motive for killing the Governor was to seek to make the people, black people in particular, become aware of the evilness and wickedness of the colonialist system in this island. Secondly, the motive was to show that these colonialists were just ordinary people like ourselves who eat, sleep and die just like anybody else and that we need not stand in fear and awe of them.[7]

A co-accused named Larry Tacklyn was acquitted of assassinating Sharples and Sayers but was convicted of killing Victor Rego and Mark Doe at the Shopping Centre supermarket in April 1973. Unlike Burrows, who did not care whether he was to be executed, Tacklyn expected to get a "last minute" reprieve.

Both murderers remained in Casemates Prison while the appeals process for Tacklyn was brought before the Privy Council in London. During this time, it was reported that Tacklyn passed the time playing table tennis, while Burrows took a virtual vow of silence, only communicating his thoughts and requests on scraps of paper.

Execution

Both men were hanged on 2 December 1977 at Casemates Prison. A moratorium on hanging was then in effect, and, although others had been sentenced to death in the intervening years, no one had been executed in Bermuda since the Second World War. Burrows and Tacklyn would be the last people to be executed under British rule anywhere in the world. The last hangings on British soil had occurred in 1965, while the last death sentence would be passed on the Isle of Man in 1992.[8][9] This sentence was eventually quashed and replaced by life imprisonment following retrial in 1994. Meanwhile, the death penalty in the Isle of Man had been abolished in 1993.[10]

Riots

Three days of rioting followed the executions. During the riots, the Bermuda Regiment proved too small to fulfil its role (which was considered by Major General Glyn Gilbert, the highest ranking Bermudian in the British Army, in his review of the regiment, leading to its increase from 400 soldiers to a full battalion of 750). As a consequence, at the request of the Bermuda Government, soldiers of the 1st Battalion the Royal Regiment of Fusiliers were flown in as reinforcements in the aftermath of the riots. The cost of the damages was estimated to be $2 million.[11]

Honours and decorations

On 20 December 1940, Sharples was awarded the Military Cross (MC) for "gallant conduct in action with the enemy".[12] In 1945, he was mentioned in dispatches for services in Italy.[13] In 1946, he was awarded the Silver Star, the United States Armed Forces third-highest military decoration for valor in combat.[14] He was appointed an Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE) in the 1953 Coronation Honours List.[15]

In 1972, Sharples was knighted as a Knight Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George following his appointment as Governor of Bermuda.[16]

Notes

- ^ Lieutenant Colonel Sir Richard Sharples KCMG OBE MC. Retrieved 20 September 2022.

- ^ Oliver Lindsay (1996). Once a Grenadier: The Grenadier Guards, 1945-1995. Leo Cooper. p. 249. ISBN 9780850525267.

- ^ "Family Treasure Restored to Owner

- ^ Guarding SNOWI, by Mick Pinchen, Royal Marine

- ^ "Baroness Sharples Obituary". The Times newspaper. 3 June 2022. Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- ^ "Assassination of Governor Sir Richard Sharples Bermuda Buck". Bernews. Retrieved 13 May 2020.

- ^ Orr, T. (2008). Bermuda. Cultures of the World (First Edition). Marshall Cavendish Benchmark. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-7614-3115-2.

- ^ Browne, Anthony (23 October 2002). "Death penalty abolished on all British territory". The Times. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ "Manx court sentences man to be hanged". Independent.co.uk. 10 July 1992.

- ^ "Capital Punishment in the Isle of Man in the late 20th Century: The Macabre Dance". 26 November 2020. Retrieved 18 May 2024.

- ^ "Bermuda Online: British Army in Bermuda from 1701 to 1977". Archived from the original on 14 April 2013. Retrieved 23 September 2012.

- ^ "No. 35020". The London Gazette (Supplement). 20 December 1940. p. 7199.

- ^ "No. 36886". The London Gazette (Supplement). 9 January 1945. p. 325.

- ^ "No. 37761". The London Gazette (Supplement). 15 October 1946. p. 5138.

- ^ "No. 39863". The London Gazette (Supplement). 26 May 1953. p. 2939.

- ^ "No. 45703". The London Gazette (Supplement). 16 June 1972. p. 7265.

Sources

The Ottawa Citizen, 11 March 1973,**as first reported.**

The Black Panthers: Their Dangerous Bermudian Legacy, Mel Ayton 2006.