Rashid Johnson

Rashid Johnson | |

|---|---|

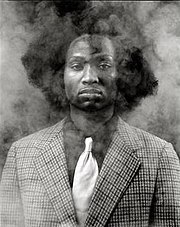

Johnson in 2008 | |

| Born | 1977 Illinois, US |

| Education | Columbia College Chicago School of the Art Institute of Chicago |

| Occupation | Artist |

| Years active | 1996-present |

| Spouse | Sheree Hovsepian |

| Children | 1 |

| Relatives | Chaka Patterson, brother & Maya Odim, sister |

Rashid Johnson (born 1977) is an American artist who produces conceptual post-black art.[1][2][3] Johnson first received critical attention in 2001 at the age of 24, when his work was included in Freestyle (2001) curated by Thelma Golden at the Studio Museum in Harlem.[4] He studied at Columbia College Chicago and the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and his work has been exhibited around the world.[5]

Johnson is known for several bodies of work in different media, including photography and painting. In addition to photography, Johnson makes audio installations, video, and sculpture. Johnson is known for both his unusual artistic productions and for his process of combining various aspects of science with black history.

Early life

Johnson was born in Illinois to an academic and scholar mother, Cheryl Johnson-Odim,[6] [7] and a Vietnam-war veteran father, Jimmy Johnson, who was an artist but worked in electronics. His parents divorced when he was 2 years old[8] and his mother remarried a man of Nigerian descent.[9] Johnson has stated that growing up his family was based in afrocentrism and that his family celebrated Kwanzaa.[10]

Johnson was raised in the Wicker Park neighborhood of Chicago, Illinois and Evanston, Illinois, a suburb.[11] A photography major,[12] he earned a 2000 Bachelor of Fine Arts from Columbia College Chicago and a 2005 Master of Fine Arts from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.[13] While at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, one of his mentors was Gregg Bordowitz.[14]

Johnson followed a generation of black artists who focused on the "black experience" and grew up in a generation that was influenced by hip hop and Black Entertainment Television. Because of his generation's high exposure to black culture within pop culture, his contemporary audiences have a greater understanding of the "black experience," which has enabled him to achieve a deeper race and identity interaction.[15]

His work has been exhibited at the Art Institute of Chicago; the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; the Detroit Institute of Arts; the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis; the Corcoran Museum of Art, Washington, DC; the Institute of Contemporary Photography, New York; the Brooklyn Museum of Art, New York; and the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago.[13]

Career

Early career

As a college junior, he opened his first show at the Schneider Gallery.[12] By 2000, he had earned a reputation for his unique photo-printing process and political content.[16][17][18][1][4][19] The Freestyle exhibition at the Studio Museum in 2001 is credited with launching Johnson's career. The curator of the show, Thelma Golden, is credited with coining the term "post-black art" in relation to that exhibit, although some suggest the term is attributable to the 1995 book The End of Blackness by Debra Dickerson, who is a favorite of Johnson's.[15] The term post-black now refers to art in which race and racism are prominent, but where the importance of the interaction of the two is diminished.[20]

Johnson's most controversial exhibition was entitled Chickenbones and Watermelon Seeds: The African American Experience as Abstract Art. The subject matter was a series of stereotypical African-American food culture items such as watermelon seeds, black-eyed peas, chicken bones, and cotton seeds placed directly onto photographic paper and exposed to light using an iron-reactive process.[21]

In 2002, he exhibited at the Sunrise Museum in Charleston, West Virginia. The exhibit, entitled Manumission Papers, was named for the papers that freed slaves were required to keep to prove their freedom. The exhibition was described as being as much a cultural commentary as an imagery display, and it related to the previous "Chickenbones" exhibit. He geometrically arranged abstractions of feet, hands, and elbows in shapes such as cubes, church windows and ships. This was a considered as study in racial identity because the body parts were not identifiable.[21] Also in 2002, presenting his photographic work using chicken bones, Johnson exhibited at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, as part of the UBS 12 x 12: New Artists, New Work series.[22]

In 2002 he exhibited his homeless men in the Diggs Gallery of Winston-Salem State University. The exhibit was entitled Seeing in the Dark and used partially illuminated subjects against deep black backgrounds.[23] He also exhibited his homeless men work, including George (1999), in Atlanta, Georgia as part of the National Black Arts Festival at City Gallery East in July and August 2002.[24] George was part of the Corcoran Gallery of Art November 2004 – January 2005 Common Ground: Discovering Community in 150 Years of Art, Selections From the Collection of Julia J. Norrell exhibition.[25] George and the Common Ground exhibition appeared in several other places including the North Carolina Museum of Art in 2006.[26]

He took part in the Chicago Department of Cultural Affairs artist Open Studio Program rotation in the Chicago Landmark/National Register of Historic Places Page Brothers Building during the summer of 2003 with a three-week exhibition. He explored the "historical and contemporary nature of photography".[27] At that time, he was represented by George N'Namdi, who owned G.R. N'Namdi, the oldest African-American-owned, exhibiting commercial gallery in the country.[28][29]

In conjunction with the Renaissance Society at the University of Chicago, Rashid Johnson exhibited The Evolution of the Negro Political Costume in December 2004. He presented replicas of three outfits worn by African-American politicians. He included a late 1960s dashiki worn by Jesse Jackson, a 1980s running suit worn by Al Sharpton in the '80s and a business suit worn by then United States Senator-elect Barack Obama. The presentation, which invited inspection, was as likely to evoke humorous response to the Jackson dashiki as well as critical commentary about the presentation of political attire.[30]

Johnson explored the theme of escapism at the Indianapolis Museum of Contemporary Art in a show entitled The Production of Escapism: A Solo Project by Rashid Johnson. He addressed distraction and relief from reality through art and fantasy. Johnson used photos, video and site-specific installation to study escapist tendencies through often with a sense of humor that bordered on the absurd.[31]

Post-graduate career

During the summer of 2005, he took part in a Chicago Cultural Center artist exchange program exhibition featuring five emerging Chicago contemporary artists and five from Kaohsiung, Taiwan. Half of the ten were women (four from Taiwan). As part of the Crossings exhibition almost all artists had their first chance to exhibit in the country of the others. In this forum, Chicago Tribune art critic Alan G. Artner said Johnson's audio selection imposed his artistry on all the other exhibits since he chose a rap song combined with a blunt video.[32][33] Artner became a Johnson detractor in 2005 when Johnson had this and another simultaneous exhibit appearing in Chicago. He described Johnson's exploration of the politics of race as "sloganeering or cute self-advertising" in his two-dimensional works, and his apolitical three-dimensional installations as "glib and superficial" representations. He classified Johnson's work as more suitable for the audience seeking nothing more than American pop culture.[34] Artner also derided Johnson's short video contribution to the Art Institute of Chicago's Fool's Paradise exhibition as a "conflation of gospel singing with beat boxing ... that says nothing worth saying about race."[35] Other Chicago critics describe Johnson's subsequent work as relatively hip.[36]

The following year, after obtaining his master's degree, he moved to the Lower East Side in New York City,[11] where he taught at the Pratt Institute.[37] Although he is generally referred to as a photographer and sometimes referred to as a sculptor, in certain contexts, he has been referred to as an artist-magician.[38]

In an ensemble 2006 showing entitled Scarecrow, Johnson exhibited a life-sized photographic nude self-portrait that was supposed to be menacing and abrasive, but that was perceived as interesting and amusing.[39] His Summer 2007 "Stay Black and Die" work in The Color Line exhibition at the Jack Shainman Gallery left one art critic from The New York Times wondering whether he was viewing a warning or exhortation.[40] However, at the same time he participated in the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art's For Love of the Game: Race and Sport in America exhibition that seemed to clearly address manners in which questions about race have been asked and answered on American sports fields of play.[41]

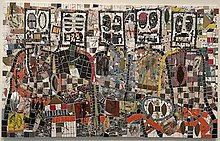

As a post-black artist, his mixed-media work, such as his Spring 2008 exhibition The Dead Lecturer, plays on race while diminishing its significance by playing with contradictions, coded references and allusions (E.g., The New Negro Escapist Social and Athletic Club (Emmett), right).[42] The exhibit was described as "a fictional secret society of African-American intellectuals, a cross between Mensa and the Masons" that was a challenge to either condemn or endorse.[43]

Rise to prominence

In November 2011, Johnson was named one of six finalists for the Hugo Boss Prize.[44][45] In 2012, mega-gallery Hauser & Wirth announced their first solo exhibition with Johnson at their Upper East Side location in New York.[46]

In April 2012, the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, presented Johnson's first major museum solo exhibition in the US, titled Message to Our Folks.[47] MCA Pamela Alper Associate Curator Julie Rodrigues Widholm curated the exhibition in close collaboration with the artist. The exhibition was a survey of the previous ten years of the artist's work. Additionally, a new work commissioned by the MCA was shown for the first time.[48] The exhibition subsequently travelled to the Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum in St. Louis, and the High Museum of Art in Atlanta. The Perez Art Museum Miami, acquired the two-dimensional piece Tribe, produced right after the MCA show was open, in 2013.[49]

In 2013, Johnson was one of the commissioned artists for the Performa Biennial.

In 2021, the Metropolitan Opera in New York City unveiled The Broken Nine, Johnson's two-panel mosaic, ceramic, and branded wood work commissioned for the Opera's interior grand tier landings.[50] The same year, Johnson's works were added to the permanent collections of the Museum of Modern Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. He also began serving on the boards of Performa, Ballroom Marfa, and the Guggenheim Museum.

In 2022, Johnson's Surrender Painting "Sunshine" (2022) sold for $3 million, a record for the artist at auction.[51]

At Bonhams Post-War and Contemporary Art Sale in London of June 2022, Johnson's wax and spray enamel work "Carver", (2012). Sold for £264,900.[52]

Throughout that latter 2010's, Johnson addressed the idea of mental health in multiple series of works, namely Anxious Men and Anxious Audiences and Broken Men.[53]

Film career

Johnson made his directorial debut with Native Son, a film adaptation of Richard Wright's acclaimed 1940 novel of the same name. It was announced in 2018 that Johnson had tapped playwright Suzan Lori-Parks to adapt the novel into a screenplay,[54][55] and cast Ashton Sanders in the lead role of Bigger Thomas.[56] The film was produced by A24 and premiered at Sundance Film Festival in January 2019. HBO Films acquired the movie hours before its premiere.[57] Critical reception of the film was mixed. Richard Roeper gave the film a rating of 3/4 stars, and noted the actors' "electric" performances.[58] Troy Patterson wrote in the New Yorker that the film suffered from "intelligent grappling with a classic text" that is ultimately "obsolete".[59] Jennifer Vineyard wrote in the New York Times that the movie "isn't a masterpiece" but "has much to admire", citing its "striking visual compositions", "tense atmosphere", and "Sanders' nuanced performance".[60] Review aggregation site Rotten Tomatoes gives the film a score of 61%, based on reviews from 51 critics, and an average rating of 6.10/10, with the general consensus stated as follows: "Native Son's struggles with its problematic source material are uneven but overall compelling, thanks largely to Ashton Sanders' poised work in the central role."[61] Johnson won "Outstanding Directing in a Motion Picture (Television)" at the 51st NAACP Image Awards for his work on Native Son.[62]

Techniques and processes

"I was very proud when Barack got the nomination, ... But I wasn't proud for black people—I was kind of proud for white people."

Johnson uses "alchemy, divination, astronomy, and other sciences that combine the natural and spiritual worlds" to augment black history. According to a Columbia College Chicago publication, Johnson works in a variety of media with physical and visual materials that have independent artistic significance and symbolism but that are augmented by their connections to black history.[13][15] According to the culture publication Flavorpill, he challenges his viewers with photography and sculpture that present the creation and dissemination of norms and expectations.[13] However, the Chicago Tribune describes the productions resulting from his processes as lacking complexity or depth.[34] Seattle Post-Intelligencer writer Regina Hackett described Johnson as an artist who avoids the struggles of black people and explores their strengths, while inserting himself as subject in his "aesthetic aspirations" through a variety of forums.[4]

Johnson has garnered national attention for both his unusual subject matter and for his process.[21] In addition to portrait photography, Johnson is known for his use of a 19th-century process[21][12] that uses Van Dyke brown, a transparent organic pigment, and exposure to sunlight. He achieves a painterly feel with his prints with the application of pigment using broad brush strokes.[28] He uses a 8-by-10-inch (20 by 25 cm) Deardorff, which forces him to interact with his subjects.[63]

His use of shea butter and tiles in his, respective, sculptural and mosaic work have significant meaning to Johnson.[64] The former being a "signifier of African identity,"[64] whereas the latter have a more personal connection for him. As a student, a Russian and Turkish Bathouse became a place of refuge, with him viewing the white tiles as a canvas.[64] He would even take his college assigned-reading in there with him.[64]

Other activities

Johnson served on the jury that selected Otobong Nkanga for the Nasher Prize in 2024.[65]

Personal life

Johnson is married to artist Sheree Hovsepian.[66] They live in New York City and have a son.[67][64]

Awards

- 2012: David C. Driskell Prize

Exhibitions

Johnson has staged numerous solo shows at museums and galleries in the United States and internationally. His notable solo shows include The Rise and Fall of the Proper Negro (2003), Monique Meloche Gallery, Chicago;[68] The Production of Escapism (2005), Indianapolis Contemporary;[69] Smoke and Mirrors (2009), SculptureCenter, New York;[70] Rashid Johnson: Message to Our Folks (2012-2013), originating at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago;[71] The gathering (2013), Hauser & Wirth, Zurich;[72] Anxious Men (2015), Drawing Center, New York;[73] Provocations: Rashid Johnson (2018), Institute for Contemporary Art, Richmond, Virginia;[74] and The Crisis (2021), Storm King Art Center, New Windsor, New York.[75]

He has also participated in many group shows, including Freestyle (2001), Studio Museum in Harlem, New York;[76] IBCA 2005, Prague;[77] ILLUMInations (2011), 54th Venice Biennale;[78] Shanghai Biennale (2012);[79] Prospect. 4: The Lotus in Spite of the Swamp (2017), Prospect New Orleans;[80] and the Liverpool Biennial (2021).[81]

Notable works in public collections

- Michael (1998), Art Institute of Chicago[82]

- Calvin (1999), National Museum of African American History and Culture, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.[83]

- Jonathan (1999), Whitney Museum, New York[84]

- Self-Portrait with my hair parted like Frederick Douglass (2003), Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago[85]

- The Evolution of the Negro Political Costume (2004), Brooklyn Museum, New York[86]

- Untitled (2007), Seattle Art Museum[87]

- Black Steel in the Hour of Chaos (2008), Whitney Museum, New York[88]

- The New Negro Escapist Social and Athletic Club (Emmett) (2008), National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.[89]

- The New Negro Escapist Social and Athletic Club (Thurgood) (2008), Rubell Museum, Miami;[90] and Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa, Cape Town, South Africa[91]

- Thurgood in the Hour of Chaos (2009), Brooklyn Museum, New York;[92] Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco;[93] Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia;[94] San Francisco Museum of Modern Art;[95] and Whitney Museum, New York[96]

- The New Negro Escapist Social and Athletic Club (Marcus) (2010), Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago[97]

- Our People, Kind of (2010), Museum of Modern Art, New York[98]

- The Treatment (2010), Walker Art Center, Minneapolis[99]

- The New Black Yoga (2011), Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York[100]

- River Crossing (2011), Detroit Institute of Arts[101]

- The Sweet Science (2011), Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond[102]

- Four for the Talking Cure (2012), Los Angeles County Museum of Art[103]

- Tribe (2013), Pérez Art Museum Miami[104]

- Planet (2014), National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.[105]

- Fatherhood (2015), Baltimore Museum of Art[106]

- Untitled (2015), Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York;[107] Museum of Fine Arts, Boston;[108] and Whitney Museum, New York[109]

- Untitled Anxious Audience (2017), Milwaukee Art Museum[110]

- Untitled (Anxious Crowd) (2018), Cleveland Museum of Art;[111] Detroit Institute of Arts;[112] and Whitney Museum, New York[113]

- Untitled Escape Collage (2018), Dallas Museum of Art[114]

- The Broken Five (2019), Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York[115]

- Anxious Red Painting November 29th (2020), Art Institute of Chicago[116]

- Stacked Heads (2020), Storm King Art Center, New Windsor, New York[117]

- The Bruising: For Jules, The Bird, Jack and Leni (2021), Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas[118]

- Standing Broken Men (2021), Cleveland Museum of Art[119]

- Untitled Anxious Red (2021), National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.[120]

Bibliography

- Claudia Rankine, Sampada Aranke, Akili Tommasino, Rashid Johnson, Phaidon, London, 2023

- Monica Davis, Claudia Schreier, Rashid Johnson: The Hikers, Hauser & Wirth, Aspen, 2021

- Ruth Addison, Kate Fowle, Anton Belov, Rashid Johnson, Garage Museum of Contemporary Art, Moscow, 2016

- Julie Rodrigues Widholm, Paul Beatty, Madeleine Grynsztejn, Rashid Johnson: Message to Our Folks, Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, 2012

References

- ^ a b Cotter, Holland (May 11, 2001). "ART REVIEW; A Full Studio Museum Show Starts With 28 Young Artists and a Shoehorn". The New York Times. Retrieved January 11, 2009.

- ^ Johnson, Ken (December 5, 2008). "The Art Fair as Outlet Mall". The New York Times. Retrieved January 11, 2009.

- ^ von Rhein, John; Reich, Howard; Artner, Alan G; Christiansen, Richard (December 30, 2001). "Planner. Our Critic' Choices". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved January 11, 2009.

- ^ a b c Hackett, Regina (August 9, 2007). "Rashid Johnson, the "post-black" art movement, and a new take on Olympia". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Retrieved January 11, 2009.

- ^ Shaw, Cameron (October 28, 2015). "Looking Deeply at the Art of Rashid Johnson". The New York Times. Retrieved November 1, 2015.

- ^ Rice, Chris Maul (March 17, 2022). "Overblown ego: Parents don't do kids any favors when they praise too much". Chicago Tribune. ProQuest 418486600. Retrieved April 17, 2023.

- ^ West, Stan (January 16, 2007). "Meet Dr. Johnson-Odim, Dominican's new provost". Oak Park. Retrieved November 1, 2015.

- ^ Suarez de Jesus, Carlos (September 13, 2012). "Rashid Johnson's MAM Exhibit Uses Everyday Objects to Explore Race and Identity". Miami New Times. Retrieved November 1, 2015.

- ^ Goldstein, Andrew M. (December 31, 2013). "Q&A: Rashid Johnson on Making Art "About the Bigger Issues in Life"". Artspace. Retrieved November 1, 2015.

- ^ Woods, Ange-Aimée (February 21, 2014). "Five Questions: Brooklyn-based visual artist Rashid Johnson". Colorado Public Radio. Retrieved November 1, 2015.

- ^ a b Drury, Amalie (December 2008). "The Artist". Chicago Social. Chicago, Illinois: 137.

- ^ a b c Fuller, Janet Rausa (October 8, 2000). "13 a lucky number for arts lovers". Chicago Sun-Times. Newsbank. Retrieved January 11, 2009.

- ^ a b c d "Rashid Johnson". Flavorpill. September 9, 2008. Archived from the original on July 21, 2009. Retrieved January 11, 2009.

- ^ Stackhouse, Christopher (April 4, 2012). "Rashid Johnson". Art in America. Archived from the original on September 5, 2015. Retrieved November 1, 2015.

- ^ a b c d Wiens, Ann (November 2008). "Spot On: Rashid Johnson". Demo. Columbia College Chicago. Archived from the original on July 3, 2010. Retrieved January 12, 2009.

- ^ Johnson, Ken (February 4, 2000). "ART IN REVIEW; National Black Fine Art Show". The New York Times. Retrieved January 11, 2009.

- ^ Fuller, Janet Rausa (October 8, 2000). "Thirteen rising stars - Portraits of the Chicago artists as up-and-coming visual forces". Chicago Sun-Times. Newsbank. Retrieved January 11, 2009.

- ^ Maes, Nancy (January 11, 2001). "Setting Your Sites - Web Favorites Reveal Personality Traits Of Prominent Chicagoans". Chicago Tribune. Newsbank. Retrieved January 11, 2009.

- ^ Kilian, Micheal (May 20, 2001). "The Met pays homage to Jackie Kennedy". Chicago Tribune. Newsbank. Retrieved January 11, 2009.

- ^ Calder, Jaime (2008). "Review: Rashid Johnson/Monique Meloche". Newcity Art. Newcity Communications, Inc. Retrieved January 12, 2009.

- ^ a b c d Shawver, D.B. (January 26, 2002). "Prominence of artists makes exhibit important - Pieces by artists work well together". Charleston Daily Mail. Newsbank. Retrieved January 11, 2009.

- ^ "Rashid Johnson". Galerie Guido W. Baudach. Archived from the original on June 9, 2011. Retrieved June 10, 2011.

- ^ "Reception To Open 3 Shows At Diggs". Winston-Salem Journal. Newsbank. June 2, 2002. Retrieved January 11, 2009.

- ^ Cullum, Jerry (July 19, 2002). "National Black Arts Festival: VISUAL ARTS: 15 visions of African-American identity". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Newsbank. Retrieved January 11, 2009.

- ^ Shaw-Eagle, Joanna (November 13, 2004). "A 'spiritual' collection - On view at Corcoran". The Washington Times. Newsbank. Retrieved January 11, 2009.

- ^ Sung, Ellen (May 7, 2006). "Collector finds common ground in diverse works". The News & Observer. Newsbank. Retrieved January 12, 2009.

- ^ Lenoir, Lisa (May 18, 2003). "Artists - on display - Public project gives observers a peek into artistic process". Chicago Sun-Times. Newsbank. Retrieved January 11, 2009.

- ^ a b Cohen, Keri Guten (November 9, 2003). "Textured Paint, In a Riot Of Color - British And Caribbean Influences Are Apparent". Detroit Free Press. Newsbank. Retrieved January 11, 2009.

- ^ Stein, Lisa (June 20, 2003). "N'Namdi's broad art world - Art but one of many facets in the universe of gallery pioneer". Chicago Tribune. Newsbank. Retrieved January 11, 2009.

- ^ Camper, Fred (December 17, 2004). "Artists' 'Perfect Union' a view to a complex world". Chicago Tribune. Newsbank. Retrieved January 12, 2009.

- ^ Slosarek, Steve (March 4, 2005). "Day by Day - What's new, promising or a best bet". The Indianapolis Star. Newsbank. Retrieved January 12, 2009.

- ^ Artner, Alan G. (August 11, 2005). "10 artists make 'Crossings' - Exhibit features works from Taiwan, Chicago". Chicago Tribune. Newsbank. Retrieved January 12, 2009.

- ^ Nance, Kevin (August 2, 2005). "East meets West: 'Crossings: 10 Artists From Chicago & Kaohsiung' brings together young talent at Cultural Center". Chicago Sun-Times. Newsbank. Retrieved January 12, 2009.

- ^ a b Artner, Alan G. (September 30, 2005). "Electric talents left idle - Versteeg's show can be interesting, falls short overall". Chicago Tribune. Newsbank. Retrieved January 12, 2009.

- ^ Artner, Alan G. (August 31, 2006). "Wisdom hard to find in 'Fool's Paradise' - Show explores meaning of place, but mostly is lost". Chicago Tribune. Newsbank. Retrieved January 12, 2009.

- ^ Hawkins, Margaret (April 6, 2007). "A '60s-inspired installation is trip that's worth taking". Chicago Sun-Times. Newsbank. Retrieved January 12, 2009.

- ^ Nelson, Karin (December 9, 2007). "Snuggle and Sip". The New York Times. Retrieved January 11, 2009.

- ^ Berry, S.L. (January 7, 2005). "The art of elsewhere - Art lovers can sample other galleries while the IMA is closed". The Indianapolis Star. Newsbank. Retrieved January 12, 2009.

- ^ "The Listings: June 30 - July 6". The New York Times. June 30, 2006. Retrieved January 11, 2009.

- ^ "Art in Review". The New York Times. July 27, 2007. Retrieved January 11, 2009.

- ^ Eagan, Matt (June 7, 2007). "Examining Sports and Race". The Hartford Courant. Newsbank. Retrieved January 12, 2009.

- ^ Rosenberg, Karen; Cotter, Holland; Johnson, Ken (March 28, 2008). "Art in Review". The New York Times. Retrieved January 11, 2009.

- ^ Cotter, Holland (March 30, 2008). "The Topic Is Race; the Art Is Fearless". The New York Times. Retrieved January 11, 2009.

- ^ Vogel, Carol (November 25, 2011). "Six Named as Finalists for Hugo Boss Prize". The New York Times. Retrieved January 5, 2012.

- ^ "Guggenheim Museum Announces Short List For The Hugo Boss Prize 2012". The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation. November 28, 2011. Archived from the original on October 19, 2013. Retrieved January 5, 2012.

- ^ Spears, Dorothy (January 5, 2012). "Fusing Identity: Dollops of Humor and Shea Butter". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 11, 2022.

- ^ Rousseau, Caryn (April 16, 2012). "Rashid Johnson Museum Of Contemporary Art Solo Exhibition Opens This Month". The Huffington Post. Retrieved June 21, 2012.

- ^ "Rashid Johnson: Message to Our Folks". Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago. Archived from the original on June 10, 2011. Retrieved June 10, 2011.

- ^ "Tribe • Pérez Art Museum Miami". Pérez Art Museum Miami. Retrieved September 12, 2023.

- ^ Sheets, Hilarie M. (September 23, 2021). "In Rashid Johnson's Mosaics, Broken Lives Pieced Together". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 12, 2022.

- ^ Kazakina, Katya (November 18, 2022). "Christie's Sold More Than $2 Billion Worth of Art in New York, But Its 20th and 21st Century Auctions Had Major Disappointments". Artnet News. Retrieved December 12, 2022.

- ^ "Bonhams : Stik Triumphs at Bonhams Post-War and Contemporary Art Sale in London". www.bonhams.com. Retrieved January 18, 2024.

- ^ "Rashid Johnson on broken men, the black body and why Trump is bad for art". the Guardian. November 25, 2019. Retrieved March 9, 2021.

- ^ Fleming, Mike Jr. (March 15, 2018). "A24 Lands 'Native Son' WW Rights Package: Rashid Johnson Helms, Ashton Sanders To Lead Ensemble On Richard Wright Novel Adaptation". Deadline. Retrieved December 11, 2022.

- ^ Kinsella, Eileen (February 21, 2017). "Rashid Johnson to Direct Adaptation of 'Native Son'". Artnet News. Retrieved December 11, 2022.

- ^ Ebiri, Bilge (January 27, 2019). "Native Son Breathes Life Into One of Literature's Most Heartbreaking Characters". Vulture. Retrieved December 11, 2022.

- ^ Rea, Naomi (January 25, 2019). "HBO Instantly Snapped Up Artist Rashid Johnson's Directorial Debut 'Native Son' at Sundance". Artnet News. Retrieved December 11, 2022.

- ^ "Two strong stars enhance a 'Native Son' updated for now". Chicago Sun-Times. April 5, 2019. Retrieved December 11, 2022.

- ^ "A New Adaptation of "Native Son" Reaches the Limits of What the Text Has to Offer". The New Yorker. April 5, 2019. Retrieved December 11, 2022.

- ^ Vineyard, Jennifer (April 1, 2019). "The Best Movies and TV Shows New to Netflix, Amazon and More in April". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 11, 2022.

- ^ Native Son, retrieved December 11, 2022

- ^ Variety Staff (February 23, 2020). "NAACP Winners 2020: The Complete List". Variety. Retrieved December 11, 2022.

- ^ Eskin, Leah (June 17, 2001). "Attachments. What Would You Take from a Burning Building?". Chicago Tribune. Newsbank. Retrieved January 11, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e "An interview with Rashid Johnson". Apollo Magazine. November 8, 2020. Retrieved March 9, 2021.

- ^ Maximilíano Durón (5 October 2023), Otobong Nkanga Wins $100,000 Nasher Prize for Sculpture ARTnews.

- ^ Browne, Alix (November 25, 2014). "Artists in Residence Rashid Johnson and Sheree Hovsepian can't help but bring their work home". W Magazine. Archived from the original on October 31, 2015. Retrieved November 1, 2015.

- ^ Paddle8 (April 15, 2015). "8 Things to Know About Rashid Johnson". Paddle8. Retrieved November 1, 2015.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Rashid Johnson: The Rise and Fall of the Proper Negro". Monique Meloche. Monique Meloche Gallery. Archived from the original on August 15, 2022. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ Vaughn, Kenya (September 19, 2013). "Celebrated contemporary artist spotlighted at Kemper Art Museum". STL American. The St. Louis American. Archived from the original on June 16, 2017. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ "Smoke and Mirrors". SculptureCenter. Archived from the original on April 23, 2022. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ "Rashid Johnson: Message to Our Folks". MCAChicago. Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago. Archived from the original on March 3, 2022. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ "The Gathering". HauserWirth. Hauser & Wirth. Archived from the original on August 15, 2022. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ "Anxious Men". Drawing Center. Archived from the original on May 24, 2022. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ "Provocations: Rashid Johnson". ICA VCU. Virginia Commonwealth University. Archived from the original on October 15, 2021. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ "The Crisis". Storm King. Storm King Art Center. Archived from the original on December 15, 2021. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ Cotter, Holland (May 11, 2001). "ART REVIEW; A Full Studio Museum Show Starts With 28 Young Artists and a Shoehorn". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 24, 2022. Retrieved August 16, 2022.

- ^ "IBCA 2005 INTERNATIONAL BIENNALE OF CONTEMPORARY ART". e-flux. Archived from the original on May 19, 2021. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ "Rashid Johnson. ILLUMInations". universes.art. Universes in Universe. Archived from the original on October 28, 2020. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ "Shanghai Biennale 2012". Power Station of Art. Archived from the original on August 15, 2022. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ "Prospect.4". Prospect New Orleans. Archived from the original on March 26, 2022. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ "Rashid Johnson, Liverpool Biennial". Bienniel. Liverpool Biennial. Archived from the original on May 11, 2021. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ "Michael". ArtIC. Art Institute of Chicago. 1998. Archived from the original on February 3, 2022. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ "Calvin". NMAAHC. Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on September 24, 2017. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ "Jonathan". Whitney. Whitney Museum. Archived from the original on November 3, 2020. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ "Self-Portrait with my hair parted like Frederick Douglass". MCAChicago. Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago. Archived from the original on August 15, 2022. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ "The Evolution of the Negro Political Costume". Brooklyn Museum. Archived from the original on August 5, 2022. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ "Untitled". Seattle Art Museum. Archived from the original on December 9, 2019. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ "Black Steel in the Hour of Chaos". Whitney. Whitney Museum. Archived from the original on August 15, 2022. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ "The New Negro Escapist Social and Athletic Club (Emmett)". NGA. National Gallery of Art. Archived from the original on August 5, 2022. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ "Rashid Johnson". Rubell Museum. Archived from the original on November 14, 2022. Retrieved November 14, 2022.

- ^ "THE NEW NEGRO ESCAPIST SOCIAL AND ATHLETIC CLUB (THURGOOD)". ZeitzMOCAA. Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa. Archived from the original on November 14, 2022. Retrieved November 14, 2022.

- ^ "Thurgood in the House of Chaos". Brooklyn Museum. Archived from the original on April 25, 2022. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ "Thurgood in the House of Chaos". FAMSF. Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. Archived from the original on November 14, 2022. Retrieved November 13, 2022.

- ^ "Thurgood in the House of Chaos". PAFA. Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. December 28, 2014. Archived from the original on August 15, 2022. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ "Thurgood in the Hour of Chaos". SFMoMA. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Archived from the original on August 15, 2022. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ "Thurgood in the Hour of Chaos". Whitney. Whitney Museum. Archived from the original on November 3, 2020. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ "The New Negro Escapist Social and Athletic Club (Marcus)". MCA Chicago. Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago. Archived from the original on November 14, 2022. Retrieved November 14, 2022.

- ^ "Our People, Kind of". MoMA. Museum of Modern Art. Archived from the original on November 7, 2021. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ "The Treatment". WalkerArt. Walker Art Center. Archived from the original on August 3, 2021. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ "The New Black Yoga". Guggenheim. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. Archived from the original on January 20, 2022. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ "River Crossing". DIA. Detroit Institute of Arts. Archived from the original on November 14, 2022. Retrieved November 14, 2022.

- ^ "The Sweet Science". VMFA. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. Archived from the original on August 15, 2022. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ "Four for the Talking Cure". LACMA. Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Archived from the original on February 5, 2018. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ "Tribe". PAMM. Pérez Art Museum Miami. Archived from the original on August 15, 2022. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ "Planet". NGA. National Gallery of Art. Retrieved February 13, 2023.

- ^ "Contemporary Collection". ArtBMA. Baltimore Museum of Art. Archived from the original on December 12, 2022. Retrieved December 12, 2022.

- ^ "Untitled". MetMuseum. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Archived from the original on April 18, 2021. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ "Two Faces". MFA. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Archived from the original on August 15, 2022. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ "Untitled". Whitney. Whitney Museum. Archived from the original on November 3, 2020. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ "Untitled Anxious Audience". MAM. Milwaukee Art Museum. Archived from the original on August 15, 2022. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ "Untitled (Anxious Crowd)". ClevelandArt. Cleveland Museum of Art. March 24, 2020. Archived from the original on July 5, 2022. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ "Untitled (Anxious Crowd)". DIA. Detroit Institute of Arts. Archived from the original on November 14, 2022. Retrieved November 14, 2022.

- ^ "Untitled (Anxious Crowd)". Whitney. Whitney Museum. Archived from the original on November 3, 2020. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ "Untitled Escape Collage". DMA. Dallas Museum of Art. Archived from the original on August 15, 2022. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ "The Broken Five". MetMuseum. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Archived from the original on September 24, 2021. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ "Anxious Red Painting November 29th". ArtIC. Art Institute of Chicago. Archived from the original on August 15, 2022. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ "Stacked Heads". Storm King. Storm King Art Center. Archived from the original on August 15, 2022. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ "The Bruising: For Jules, The Bird, Jack and Leni". Crystal Bridges. Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art. Archived from the original on August 15, 2022. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ "Standing Broken Men". ClevelandArt. Cleveland Museum of Art. January 26, 2022. Archived from the original on July 5, 2022. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ "Untitled Anxious Red". NGA. National Gallery of Art. Archived from the original on August 15, 2022. Retrieved August 15, 2022.