Syrian Railways

Modern CFS passenger train, hauled by General Electric Class U17C, north of Aleppo on the former Baghdad Railway | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Headquarters | Aleppo, Syria |

| Reporting mark | CFS |

| Locale | Syria |

| Dates of operation | 1956–present |

| Predecessor | Damas, Hamah et Prolongements Hejaz railway |

| Technical | |

| Track gauge | 1,435 mm (4 ft 8+1⁄2 in) standard gauge, 1,050 mm (3 ft 5+11⁄32 in) (narrow gauge) |

| Length | 2,750 km (1,710 mi) |

| Other | |

| Website | https://www.cfssyria.sy |

General Establishment of Syrian Railways[1] (Arabic: المؤسسة العامة للخطوط الحديدية,[2] French: Chemins de fer syriens, CFS) is the national railway operator for the state of Syria, subordinate to the Ministry of Transportation.[3] It was established in 1956 and was headquartered in Aleppo.[4][5] Syria's rail infrastructure has been severely compromised as a result of the ongoing conflict in the country.

History

The first railway in Syria opened when the country was part of the Ottoman Empire, with the 1,050 mm (3 ft 5+11⁄32 in) gauge line from Damascus to the port city of Beirut in present-day Lebanon opened in 1895. The Hejaz railway opened in 1908 between Damascus and Medina in present-day Saudi Arabia also used 1,050 mm (3 ft 5+11⁄32 in) gauge. Railways after this point were built to 1,435 mm (4 ft 8+1⁄2 in) standard gauge, including the Baghdad Railway.[6] The French wanted an extension of the standard gauge railway to connect with Palestine Railways and so agreed the building of a branch line to Tripoli, Lebanon, operated by Société Ottomane du Chemin de fer Damas-Hama et prolongements, also known as DHP.[7]

The Baghdad Railway had progressed as far as Aleppo by 1912, with the branch to Tripoli complete, by the start of World War I; and onwards to Nusaybin by October 1918.[8] The Turks, who sided with Germany and the Central Powers, decided to recover the infrastructure south of Aleppo to the Lebanon in 1917. The Baghdad Railway created opportunity and problems for both sides, being unfinished but running just south of the then-defined Syrian–Turkish border.[7] Post war, the border was redrawn, and the railway was now north of the border. DHP reinstated the Tripoli line by 1921. From 1922 the Baghdad Railway was worked in succession by two French companies, who were liquidated in 1933 when the border was again redrawn, placing the Baghdad Railway section again in Syrian control. Lignes Syriennes de Baghdad (LSB) took over operations, a subsidiary of DHP.[7]

The next big developments in Syrian railways were due to the political manoeuvering leading up to and during World War II. As Turkey had sided with Germany in World War I, the Allies were concerned with poor transport in the area, and their ability to bring force on the Turks. Having built railways extensions in both the Eastern and Western deserts of Egypt, they initially operated services via the Hejaz Railway, but were frustrated by the need to transload goods due to the gauge break. They surveyed a route from Haifa to Rayak in 1941, but decided there were too many construction difficulties. The standard gauge line from Beirut to Haifa was eventually built by Commonwealth military engineers from South Africa and Oceania during World War II, in part supplied by a 1,050 mm (3 ft 5+11⁄32 in) gauge railway to access materials.[7] Ultimately, Turkey remained neutral and refused the Allies access to their jointly controlled sections of the Baghdad Railway, although by then the Allies had extended Palestine Railways' line from Beirut along the Lebanese coast, crossing into Syria near Al Akkari and from there to Homs, Hama and onward to connect with the Baghdad Railway at Aleppo.[7]

Locomotives servicing the Allied war effort included the British R.A. Riddles designed WD Austerity 2-10-0, four of which post war went into Syrian service, designed CFS Class 150.6.[9][10]

In 1956 all railways in Syria were nationalised, and reorganised as CFS (Chemins de Fer Syriens) from 1 January 1965. Expanded with monetary and industrial assistance from the USSR, the agreement covered the joint industrial development of the country. Covering the development of the ports of Tartus and Latakia, they were initially connected by rail to Al Akkari and Aleppo in 1968 and 1975 respectively. An irrigation project on the Euphrates, resulting in the construction of the Tabqa Dam, drove the connection of Aleppo to Al-Thawrah (1968), Raqqa (1972) Deir ez Zor (1973), reaching the old Baghdad Railway at Al Qamishli in 1976.[7]

- Hejaz railway station, Damascus

- Colonel Philibert Collet's Circassian Cavalry outside the railway station at Damascus, 26 June 1941

- Baghdad railway station in Aleppo, built in 1915

- Bridge on the Aleppo-Latakia line

- Bridge over the Euphrates river

- Latakia railway station

- Daraa railway station

- Main train station, Aleppo

- Baghdad Railway train, circa 1910

- Hejaz Railway – Damascus square and pillar. The gabled building is the Hejaz Railway Line office.

Tramway

| Location | Traction Type |

Date (From) | Date (To) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Halab حلب /Aleppo | Electric | 1929 | 1967 | [1]. |

| Dimashq دمشق /Damascus | Electric | 7 February 1907 | 1967 | [2]. |

Current system

Network

Chemins de fer Syriens | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Key | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

All 1,435 mm (4 ft 8+1⁄2 in) network and trains were operated by CFS. Using all diesel-electric powered traction, the main routes prior to the Syrian Civil War were:[4][12]

- Damascus–Homs–Hamah–Aleppo–Maydan Ikbis (- Ankara TCDD)

- Aleppo–Latakia–Tartus–Al Akkari–Homs

- Homs–Palmyra: freight only, opened for phosphates traffic, destined for the port of Tartus, in 1980

- Line runs from the oilfields of Al Qamishli in the north to the port of Latakia (750 km)

- Al Akkari (- Tripoli CEL, out of use)

- Aleppo–Deir ez-Zor–Al-Qamishli (- Nusaybin TCDD)

- Extension from Homs southwards to Damascus (194 km) was opened in 1983

- 80 km (50 mi) Tartus-Latakia line in 1992

- Al Qamishli–Al-Yaarubiyah (- IRR Iraq, out of use)

- Damascus–Sheikh Miskin–Dera'a: under construction, to replace a section of Hejaz railway

- Sheikh Miskin–Suwayda (under construction)

- Palmyra–Deir ez-Zor–Abu Kemal (- IRR Iraq) (planned)

Current proposals

Prior to the war there was a proposal for a connection with Iraq between Deir ez-Zor and Al Qa’im.[13] The abutments of bridges were built for double track but only the western trackbed was completed. The major Euphrates bridge, a steel girder construction, was completed to the southern border of Syria by 2015, just 3 km from Al Qa'im but Iraqi Railways did not complete the link. Three spans of the Euphrates bridge were destroyed as well as two sections of the approoach viaducts during the last decade of warfare. The trackbed near the bridge shows bomb craters since Google Earth imagery dated 2017. Tracklaying never reached the Euphrates bridge. However, all international routes operated by Syrian Railways were already non-operational due to severe negligence by the Syrian government. It was then officially suspended due to the outbreak of the Syrian revolution.

The restoration of the rail link with Iraq (IRR) and the proposal to extend the railway from Al-Qaim in Iraq through Al-Bukamal in Syria to Homs for a total distance of 270 kilometers and thence to Tartus are as of 2022 under discussion.[14][15]

Trackage

These were the figures prior to the ongoing Syrian conflict:

- total: 2,750 km (1,710 mi)

- standard gauge: 2,423 km (1,506 mi) 1,435 mm (4 ft 8+1⁄2 in) gauge

- narrow gauge: 327 km (203 mi) 1,050 mm (3 ft 5+11⁄32 in) gauge (2000) Chemin de Fer de Hedjaz Syrie

Operations

The network is designed wholly around diesel-electric traction. For operational purposes CFS is divided into three regions: Central, Eastern and Northern. At the end of 2004 CFS employed around 12,400 staff.

The system has a low level capacity, with top speed usually limited. A 30 km (19 mi) section of the Damascus–Aleppo line was designed for speeds reaching 120 km/h (75 mph), but most of the track has a limit of 110 km/h (68 mph). Most tracks of the CFS are limited to 80 km/h (50 mph). Operational train speed is also limited by a lack of interlocked signalling, with most of the system operating by informal signalling. The Damascus al-Hijaz railway station, which lies in the city centre, is no longer operational, and the railway connections with other cities depart from the suburban station of Qadam.

The result is that most passenger traffic has moved to air-conditioned coaches, and freight traffic dominates the operational trackage. The 2005 introduction of South Korean-built DMUs, where drivers were trained using a simulator,[16] on the Damascus–Aleppo route, and the high traffic Aleppo–Latakia route where intermediate stations are bypassed, resulted in higher usage and occupancy levels.

The only remaining section of narrow-gauge line, running from a point on the outskirts of Damascus into Jordan, is operated by Hedjaz Jordan Railway.

International connections

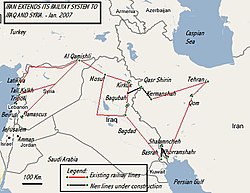

The only international connection was with Turkey, but that link was halted due to the Syrian Civil War.[17] The link with Iraq, severed in the war of 2003, was restored for a time but closed again; there was a plan to reopen it in June 2009.[18] In 2008 it was proposed to open a joint rolling stock factory with Turkish State Railways at Aleppo.

Background on trains from Istanbul to Syria: A brief history of the Taurus Express:

Agatha Christie wrote the first part of her novel Murder on the Orient Express during her stay in room 203 in Baron Hotel in Aleppo.[19] The novel doesn't start in Istanbul, or on the Orient Express. It opens on the platform at Aleppo, next to the two blue-and-gold Wagons-Lits sleeping cars of the Taurus Express bound for Istanbul. The Taurus Express was inaugurated in February 1930 by the Compagnie Internationale des Wagons-Lits, the same company that operated the Orient Express and Simplon Orient Express, as a means of extending their services beyond Istanbul to the East. It ran several times a week from Istanbul Haydarpaşa station to Aleppo and Baghdad, with a weekly through sleeper to Tripoli in Lebanon. After the second world war, the Wagons-Lits company gradually withdrew and operation of the Taurus Express was taken over by the Turkish, Syrian and Iraqi state railways. Up until the late 1980s, a twice-weekly Istanbul-Baghdad service was maintained, with weekly through seating cars from Istanbul to Aleppo. For political reasons, the through service to Baghdad was suspended and the main train curtailed at Gaziantep, but the weekly through seat cars Istanbul-Aleppo were maintained. In 2001, the Aleppo portion of the Toros Express was speeded-up and given a proper Syrian sleeping-car instead of the two very basic Turkish seat cars. You could once again travel in the security and comfort of a proper sleeper from Istanbul to Syria, and it was a great way to go.[20]

Rolling stock

Current

Motive power

The motive power in 2009 was noted as:[21][22]

| Class | Image | Axle Formula | Number | Year in Service | Power [kW] |

Max.Speed [km/h] | Traction Type* | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| unknown |

|

Steam locomotive in Bosra | ||||||

| LDE-650 |

|

Bo-Bo | 9 | 1968 | 478 | DE | Shunting locomotives built in France | |

| LDE-1200 |

|

Co-Co | 11 | 1973 | 883 | 100 | DE | TEM2 Shunting locomotives built in USSR, 346 kN tractive effort |

| LDE-1500 |

|

Co-Co | 25 | 1982 | 1102 | DE | Czechoslovakia, similar to ČSD (ČKD) ČSD Class T 669.0[23] | |

| LDE-1800 |

|

Co-Co | 26 | 1976 | 1323 | DE | American built General Electric U17C export model. 30 originally built in 2 batches | |

| LDE-2800 |

|

Co-Co | 77 | 1982 | 2058 | 100 | DE | Russian TE114, 110 originally built. Partly modernised by General Electric in 2000 by fitting 12cyclinder GE FDL of 3000 hp[24] |

| LDE-3200 |

|

Co-Co | 30 | 1999 | 2400 | 120 | DE | French Prima DE 32C AC diesel locomotives, engines by Ruston 3,200 hp (2,400 kW).[25][26] |

| DMU-5 |

|

10 | 2006 | 1680 | 120/160 | DH | Multiple unit from Hyundai Rotem, Korea for Aleppo-Damascus/Latakia long-distance services. 222 second class, 61 first class | |

| * DH = Diesel-hydraulic, Delaware = Diesel-electric | ||||||||

Passenger vehicles

The railway possessed:[21]

- Passenger carriages: almost all OSShD-Y obtained mainly from the former Deutsche Reichsbahn of German Democratic Republic, the newest of which were obtained from Căile Ferate Române of Romania and Polish State Railways.

- The stock of 483 carriages includes: 19 restaurant, 45 sleepers and 33 baggage vans. In 2001, Iranian company Wagon Pars refurbished some stock which is still in use, while the remaining unused stock lie rotting in sidings.

| Class | Image | Number | Year in Service | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type Y[27] |

|

358 | 1982–'83 | Original built for Damascus–Homs-line by VEB Bautzen. Delivered in orange-cream Städteexpress livery |

| Cars for DMU-5 |

|

N/A | 2006 | Built for Aleppo–Latakia line by Hyundai Rotem |

Freight wagons

- Goods wagons: freight trains are organised into block workings, covering shipments of: oil, natural gas, phosphates, grain, cement, containers, construction materials and other transports. Most of 4319 vehicles were built between 1960 and 1975, with the most modern stock the grain wagons imported from Iran in the early 1990s. Approximate figures for stock:

- 1294 Heavy Flat wagons

- 846 Open wagons

- 818 Oil tankers

- 762 Covered wagons

- 597 Grain wagons

- 323 Phosphate wagons

- 178 Sliding wall wagons

- 146 Self unloading wagons

- 53 Flat wagons

- 50 Natural gas tankers

- 45 Cement wagons

- 20 Water tankers

- 19 Tippers

Retired

| Class | Image | Axle Formula | Number | Year in Service | Power [kW] |

Max.Speed [km/h] | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| De Dion Bouton | railcar | 1930 | Built for Hejaz Railway | ||||

| Ganz/MAVAG R12 | railcar | ||||||

| SGP AB49000[28][29] | B'B' Railcar | 7 | 1966 | 470 | 100 | Length: 26 meters. 20 seats 1st class; 58 seats 2nd class. |

See also

- List of town tramway systems in Asia

- List of countries by rail transport network size

- Arab Mashreq International Railway

- Hejaz railway

- Hedjaz Jordan Railway

- Damascus–Amman train

- Aleppo railway station

- Transport in Syria

- Rail transport in Lebanon

- OTIF

References

- ^ "الرئيسية." (Home page) Syrian Railways. 26 October 2007. Retrieved on 22 October 2013.

- ^ "اتصـال." Syrian Railways. 16 June 2006. Retrieved on 22 October 2013.

- ^ "Hme page." Syrian Railways. 21 May 2006. Retrieved on 22 October 2013.

- ^ a b "Chemins de fer Syriens". Ferenc Valoczy. Retrieved 3 May 2009.

- ^ "Contact us." Syrian Railways. 17 June 2006. Retrieved on 22 October 2013. "Syrian Arab Republic Ministry of Transportation Syrian Railways Syria–Aleppo"

- ^ "Railways in Syria".

- ^ a b c d e f Hugh Hughes. "Middle East Railways". almashriq.hiof.no. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- ^ Glyn Williams (15 December 2020). "Railways in Syria". sinfin.net. Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- ^ Rowledge, J.W.P. (1987). Austerity 2-8-0s & 2-10-0s. London: Ian Allan.

- ^ "CFS Motive Power". Retrieved 4 May 2009.

- ^ The old Baghdad Railway from Al-Rai to Nusaybin forms the border line between Syria and Turkey, with stations accessible from Syria.

- ^ "Chemins de fer Syriens". Jaynes. Archived from the original on 27 January 2013. Retrieved 3 May 2009.

- ^ "Syrian National Railways plans". Railways in Africa. 25 March 2014.

- ^ Majda Muhsen, Anoop Menon (9 June 2022). "Iraq and Syria discuss railway link". Zawya project. Retrieved 8 September 2022.

- ^ "Iran and Iraq again agree to connect their railway networks". www.al-monitor.com. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- ^ "Syrian train simulator". YouTube. 15 April 2008. Retrieved 7 May 2009.[dead YouTube link]

- ^ Tom Brosnahan, Travel Info Exchange. "Trains Turkey <—> Syria". www.turkeytravelplanner.com. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- ^ "June launch scheduled for Iraq-Syria railway". arabiansupplychain.com. 29 April 2009. Archived from the original on 28 June 2009. Retrieved 3 May 2009.

- ^ Alan Cowell (24 February 1990). "Aleppo Journal; A Small Hotel, Its Memories Fading". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 20 May 2017.

- ^ "How to travel by train from London to Syria | Train travel in Syria".

- ^ a b "CFS". railfaneurope.net. 25 June 2008. Retrieved 3 May 2008.

- ^ "GE Locomotives in Asia & Middle East". Locopage. Retrieved 4 May 2009.

- ^ "Řada 770 (T669.0), 770.5,6 (T 669.05), 770.8 (T 669.5), "Čmelák"–Motorové lokomotivy–Atlas lokomotiv". www.zelpage.cz (in Czech). Archived from the original on 7 October 2013. Retrieved 23 June 2012.

- ^ "GE Locomotives in Asia & Middle East". locopage.net. Retrieved 4 May 2009.

- ^ "PRIMA DE 32 C AC diesel locomotives, Syria". www.transport.alstom.com. Alstom. Archived from the original on 17 October 2005.

- ^ Railfaneurope.net : Syrian diesels

- ^ HaRakevet: Rothschild PhD, Rabbi Walter (December 2004), Modelling notes–Syrian coaches. Series 17:4 issue 67

- ^ Flickr.com

- ^ Source