Ragnar Nurkse's balanced growth theory

| Part of a series on |

| Economics |

|---|

|

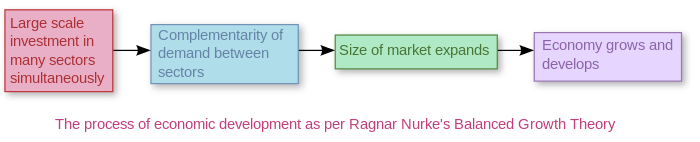

The balanced growth theory is an economic theory pioneered by the economist Ragnar Nurkse (1907–1959). The theory hypothesises that the government of any underdeveloped country needs to make large investments in a number of industries simultaneously.[1][2] This will enlarge the market size, increase productivity, and provide an incentive for the private sector to invest.

Nurkse was in favour of attaining balanced growth in both the industrial and agricultural sectors of the economy.[3] He recognised that the expansion and inter-sectoral balance between agriculture and manufacturing is necessary so that each of these sectors provides a market for the products of the other and in turn, supplies the necessary raw materials for the development and growth of the other.

Nurkse and Paul Rosenstein-Rodan were the pioneers of balanced growth theory and much of how it is understood today dates back to their work.[4]

Nurkse's theory discusses how the poor size of the market in underdeveloped countries perpetuates its underdeveloped state.[5][6] Nurkse has also clarified the various determinants of the market size and puts primary focus on productivity.[3][7] According to him, if the productivity levels rise in a less developed country, its market size will expand and thus it can eventually become a developed economy. Apart from this, Nurkse has been nicknamed an export pessimist, as he feels that the finances to make investments in underdeveloped countries must arise from their own domestic territory.[1] No importance should be given to promoting exports.[8]

Size of market and inducement to invest

The size of a market assumes primary importance in the study of what induces investment in a country. Ragnar Nurkse referenced the work of Allyn A. Young to assert that inducement to invest is limited by the size of the market.[9] The original idea behind this was put forward by Adam Smith, who stated that division of labour (as against inducement to invest) is limited by the extent of the market.[7]

According to Nurkse, underdeveloped countries lack adequate purchasing power.[7] Low purchasing power means that the real income of the people is low, although in monetary terms it may be high. If the money income were low, the problem could easily be overcome by expanding the money supply; however, since the meaning in this context is real income, expanding the supply of money will only generate inflationary pressure. Neither real output nor real investment will rise. A low purchasing power means that domestic demand for commodities is low. Apart from encompassing consumer goods and services, this includes the demand for capital as well.

The size of the market determines the incentive to invest irrespective of the nature of the economy.[6] This is because entrepreneurs invariably take their production decisions by taking into consideration the demand for the concerned product. For example, if an automobile manufacturer is trying to decide which countries to set up plants in, he will naturally only invest in those countries where the demand is high.[7] He would prefer to invest in a developed country, where though the population is lesser than in underdeveloped countries, the people are prosperous and there is a definite demand.

Private entrepreneurs sometimes resort to heavy advertising as a means of attracting buyers for their products. Although this may lead to a rise in demand for that entrepreneur's good or service, it does not actually raise the aggregate demand in the economy. The demand merely shifts from one provider to another.[5] Clearly, this is not a long-term solution.

Ragnar Nurkse concluded,

"The limited size of the domestic market in a low income country can thus constitute an obstacle to the application of capital by any individual firm or industry working for the market. In this sense the small domestic market is an obstacle to development generally."[3]

Determinants of size of market

According to Nurkse, expanding the size of the market is crucial to increasing the inducement to invest. Only then can the VICIOUS CIRCLE OF POVERTY be broken. He mentioned the following pertinent points about how the size of the market is determined:

Money supply

Nurkse emphasised that Keynesian theory shouldn't be applied to underdeveloped countries because they don't face a lack of effective demand in the way that developed countries do.[7] Their problem is to do with a lack of real purchasing power due to low productivity levels. Thus, merely increasing the supply of money will not expand the market but will in fact cause inflationary pressure.

Population

Nurkse argued against the notion that a large population implies a large market.[5] Though underdeveloped countries have a large population, their levels of productivity are low. This results in low levels of per capita real income. Thus, consumption expenditure is low, and savings are either very low or completely absent. On the other hand, developed countries have smaller populations than underdeveloped countries but by virtue of high levels of productivity, their per capita real incomes are higher and thus they create a large market for goods and services.

Geographical area

Nurkse also refuted the claim that if a country's geographical area is large, the size of its market also ought to be large.[1] A country may be extremely small in area but still have a large effective demand. For example, Japan. In contrast, a country may cover a huge geographical area but its market may still be small. This may occur if a large part of the country is uninhabitable, or if the country suffers from low productivity levels and thus has a low National Income.

Transport cost and trade barriers

The notion that transport costs and trade barriers hinder the expansion of the market is age-old. Nurkse emphasised that tariff duties, exchange controls, import quotas and other non-tariff barriers to trade are major obstacles to promoting international cooperation in exporting and importing.[7] More specifically, due to high transport costs between nations, producers do not have an incentive to export their commodities. As a result, the amount of capital accumulation remains small. To address this problem, the United Nations produced a report in 1951[10] with solutions for underdeveloped countries. They suggested that they can expand their markets by forming customs unions with neighbouring countries. Also, they can adopt the system of preferential taxation or even abolish customs duties altogether. The logic was that once customs duties are removed, transport costs will fall. Consequently, prices will fall and thus the demand will rise. However, Nurkse, as an export pessimist, did not agree with this view.[8] Export pessimism is a trade theory which is governed by the idea of "inward looking growth" as opposed to "outward looking growth". (See Import substitution industrialization)

Sales promotion

Often, it is true that a company's private endeavour to increase the demand for its products succeeds due to the extensive use of advertisement and other sales promotion technique. However, Nurkse argues that such activities cannot succeed at the macro level to increase a country's aggregate demand level.[7] He calls this the "macroeconomic paradox".[7]

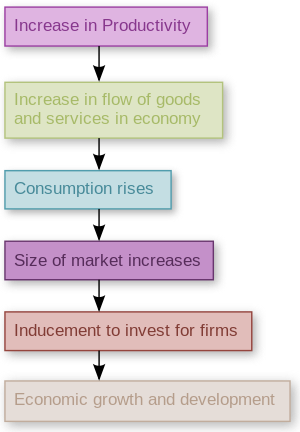

Productivity

Nurkse stressed productivity as the primary determinant of the size of the market. An increase in productivity (defined as the output per unit input) increases the flow of goods and services in the economy. As a response, consumption also rises. Hence, underdeveloped economies should aim to raise their productivity levels in all sectors of the economy, in particular agriculture and industry.[3]

For example, in most underdeveloped economies, the technology used to carry out agricultural activities is backward. There is a low degree of mechanisation coupled with rain dependence. So while a large proportion of the population (70–80%) may be actively employed in the agriculture sector, the contribution to the Gross Domestic Product may be as low as 40%.[7] This points to the need to increase output per unit input and output per head. This can be done if the government provides irrigation facilities, high-yielding variety seeds, pesticides, fertilisers, tractors etc. The positive outcome of this is that farmers earn more income and have a higher purchasing power (real income). Their demand for other products in the economy will rise and this will provide industrialists an incentive to invest in that country. Thus, the size of the market expands and improves the condition of the underdeveloped country.

Nurkse is of the opinion that Say's law of markets operates in underdeveloped countries. Thus, if the money incomes of the people rise while the price level in the economy stays the same, the size of the market will still not expand till the real income and productivity levels rise. To quote Nurkse,

"In underdeveloped areas there is generally no 'deflationary gap' through excessive savings. Production creates its own demand, and the size of the market depends on the volume of production. In the last analysis, the market can be enlarged only through all-round increase in productivity. Capacity to buy means capacity to produce."[3]

Export pessimism

Citing the limited size of the market as the main impediment in economic growth, Nurkse reasons that an increase in productivity can create a virtuous circle of growth.[7] Thus, a large scale investment programme in a wide array of industries simultaneously is the answer. The increase in demand for one industry will lead to an increase in demand for another industry due to complementarity of demands. As Say's law states, supply creates its own demand.[11]

However, Nurkse clarified that the finance for this development must arise to as large an extent as possible from the underdeveloped country itself i.e. domestically.[citation needed] He stated that financing through increased trade or foreign investments was a strategy used in the past – the 19th century – and its success was limited to the case of the United States of America. In reality, the so-called "new countries" of the United States of America (which separated from the British empire) were high income countries to begin with.[8] They were already endowed with efficient producers, effective markets and a high purchasing power. The point Nurkse was trying to make was that USA was rich in resource endowment as well as labour force. The labour force had merely migrated from Britain to USA, and thus their level of skills were advanced to begin with. This situation of outward led growth was therefore unique and not replicable by underdeveloped countries.

In fact, if such a strategy of financing development from outside the home country is undertaken, it creates a number of problems.[citation needed] For example, the foreign investors may carelessly misuse the resources of the underdeveloped country. This would in turn limit that economy's ability to diversify, especially if natural resources were plundered. This may also create a distorted social structure.[8] Apart from this, there is also a risk that the foreign investments may be used to finance private luxury consumption. People would try to imitate Western consumption habits and thus a balance of payments crisis may develop, along with economic inequality within the population.

Another reason exports cannot be promoted is because in all likelihood, an underdeveloped country may only be skilled enough to promote the export of primary goods, say agricultural goods.[7] However, since such commodities face inelastic demand, the extent to which they will sell in the market is limited.[7] Although when population is at a rise, additional demand for exports may be created, Nurkse implicitly assumed that developed countries are operating at the replacement rate of population growth. For Nurkse, then, exports as a means of economic development are completely ruled out.[1]

Thus, for a large-scale development to be feasible, the requisite capital must be generated from within the country itself, and not through export surplus or foreign investment.[6] Only then can productivity increase and lead to increasing returns to scale and eventually create virtuous circles of growth.[8]

Role of state

After World War II, a debate about whether a country should introduce financial planning to develop itself or rely on private entrepreneurs emerged. Nurkse believed that the subject of who should promote development does not concern economists. It is an administrative problem.[7] The crucial idea was that a large amount of well dispersed investment should be made in the economy, so that the market size expands and leads to higher productivity levels, increasing returns to scale and eventually the development of the country in question.[7] However, most economists who favoured the balanced growth hypothesis believed that only the state has the capacity to take on the kind of heavy investments the theory propagates. Further, the gestation period of such lumpy investments is usually long and private sector entrepreneurs do not normally undertake such high risks.[5]

Reactions

Ragnar Nurkse's balanced growth theory too has been criticised on a number of grounds. His main critic was Albert O. Hirschman, the pioneer of the strategy of unbalanced growth. Hans W. Singer also criticised certain aspects of the theory.

Hirschman stressed the fact that underdeveloped economies are called underdeveloped because they face a lack of resources, maybe not natural resources, but resources such as skilled labour and technology.[7] Thus, to hypothesise that an underdeveloped nation can undertake large scale investment in many industries of its economy simultaneously is unrealistic due to the paucity of resources.[12] To quote Hirschman,

"If a country were ready to apply the doctrine of balanced growth, then it would not be underdeveloped in the first place."[12]

Hans Singer asserted that the balanced growth theory is more applicable to cure an economy facing a cyclical downswing.[7] Cyclical downswing is a feature of an advanced stage of sustained growth rather than of the vicious cycle of poverty. Hirschman also stated that during conditions of slack activity in developed countries, the stock of resources, machines and entrepreneurs are merely unemployed, and are present as idle capacity. So in this situation, simultaneous investment in a large number of sectors is a well-suited policy. The various economic agents are temporarily unemployed and once the inducement to invest starts operating, the slump will be overcome. However, for an underdeveloped economy, where such resources are absent, this principle doesn't fit.[7]

Another contention was Nurkse's approval of Say's law, which theorises that there is no overproduction or glut in the economy.[11] Supply (production of goods and services) creates a matching demand for the output and this results in the entire output being sold and consumed. However, Keynes stated that Say's law is not operational in any country because people do not spend their entire income – a fraction of it is saved for future consumption.[11] Thus, according to Nurkse's critics, his assumption of Say's law being operational in underdeveloped countries needs greater justification.[7] Even if the section of savers is few, the tenet of putting emphasis on supply rather than demand has been widely criticised.[11][13]

Nurkse states that if demand for the output of one sector rises, due to the complementary nature of demand, the demand for the output of other industries will also experience a rise.[7] Paul Rosenstein-Rodan spoke of a similar concept called "indivisibility of demand" which hypothesises that if large investments are made in a large number of industries simultaneously, an underdeveloped economy can become developed due to the phenomenon of complementary demand.[7] However, both Nurkse and Rosenstein-Rodan only took into consideration the situation of industries that produce complementary goods.[7] There are substitute goods too, which are in competition with each other. Thus if the state pumps in large investments into the car industry, for example, it will naturally lead to a rise in the demand for petrol. But if the state makes large scale investments in the coffee sector of a country, the tea sector will suffer.

Hans Singer suggested that Nurkse's theory makes dubious assumptions about the underdeveloped economy.[7] For example, Nurkse assumes that the economy starts with nothing at hand.[5] However, an economy usually starts at a position which reflects the previous investment decisions undertaken in the country,[7] and at any given moment, an imbalance already exists. So the logical step would be to take on those investment programmes which complement the existing imbalance in the economy. Clearly, such an investment cannot be a balanced one. If an economy makes the mistake of setting out to make a balanced investment, a new imbalance is likely to appear which will require still another "balancing investment" to bring equilibrium, and so on and so forth.[7]

Hirschman believed that Nurkse's balanced growth theory wasn't in fact a theory of growth.[1] Growth implies the gradual transformation of an economy from one stage to the chronologically next stage. It entails the series of actions which leads the economy from a stage of infancy to that of maturity.[7] However, the balanced growth theory involves the creation of a brand new, self-sufficient modern industrial economy being laid over a stagnant, self-sufficient traditional economy. Thus, there is no transformation.[12] In reality, a dual economy will come into existence, where two separate economic sectors will begin to coexist in one country. They will differ on levels of development, technology and demand patterns. This may create inequality in the country.[12]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e James M. Cypher; James L. Dietz (17 July 2008). The Process of Economic Development (3rd Revised ed.). Routledge. p. 640. ISBN 978-0-415-77104-7.

- ^ Yūjirō Hayami; Yoshihisa Gōdo (2005). Development economics: from the poverty to the wealth of nations (3, illustrated ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 430. ISBN 0-19-927271-9.

- ^ a b c d e Nurkse, Ragnar (1961). Problems of Capital Formation in Underdeveloped Countries. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 163. Archived from the original on 2009-04-14. Retrieved 2017-09-10.

- ^ Hollis Chenery; T.N. Srinivasan, eds. (15 October 1988). Handbook of Development Economics, Vol. 1. North Holland. p. 882. ISBN 0-444-70337-3.

- ^ a b c d e Gaur, K.D. (1995). Development and Planning. University of Michigan: Sarap & Sons. p. 820. ISBN 81-85431-54-X.

- ^ a b c Ray, Debraj (2009). Development Economics. Oxford University Press. p. 847. ISBN 978-0-19-564900-0.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y S. K. Misra; V. K. Puri (2010). Economics Of Development And Planning—Theory And Practice (12th ed.). Himalaya Publishing House. ISBN 978-81-8488-829-4.

- ^ a b c d e Rainer Kattel; Jan A. Kregel; Eric S. Reinert (March 2009). "The Relevance of Ragnar Nurkse and Classical Development Economics" (PDF). Working Papers in Technology Governance and Economic Dynamics No. 21.

- ^ Perry G. Mehrling; Roger J. Sandilands (1999). Money and Growth: Selected Papers of Allyn Abbott Young. London and New York: Routledge. p. 464. ISBN 0-415-19155-6.

- ^ "Measures for the Economic Development of Underdeveloped Countries, Report by a Group of Experts appointed by the Secretary-General of the United Nations". May 1951.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b c d Gulati, Ambika (2006). Introductory Macroeconomic Theory – A Textbook For Class XII. New Delhi: Cambridge University Press India. p. 304. ISBN 81-7596-335-2.

- ^ a b c d Hirschman, Albert O. (1969). "Strategy of Economic Development". Yale University Press (New Haven, London): 53–4. Archived from the original on 2012-01-20. Retrieved 2017-09-10.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ L. Anderson, William. Say's Law: Were (Are) The Critics Right? (PDF). Ludwig Von Mises Institute. p. 27. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-03-09. Retrieved 2011-12-12.

External links

- "Some reflections on Nurkse's Patterns of Trade and Development by Deardorff and Stern" (PDF). University of Michigan, 27 August 2007.

- "TDESA Working Paper No. 53-Industrial Policy and Growth by Helen Shapiro" (PDF). Economic and Social Affairs.

- "The Doctrine of Market Failure and Early Development Theory by Jeannette C. Mitchell" (PDF). History of Economics Review.

- "Positional Goods, Conspicuous Consumption and the International Demonstration Effect Reconsidered by Jefferey James". World Development, Vol. 15, No. 4, pp. 49–462,1987. Archived from the original on 2012-04-26. Retrieved 2011-09-08.

- "Ragnar Nurkse's Rule-Based Approach to International Monetary Relations: Complementarities with Chicago" (PDF). University of Auckland and the Australian National University.

- "The life and time of Ragnar Nurkse" (PDF). Conference on "Ragnar Nurkse (1907–2007): Classical Development Economics and Its Relevance for Today" ,Tallinn, 31 August – 1 September 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 May 2012. Retrieved 8 September 2011.

- "Ragnar Nurkse's Development Theory" (PDF). Bremen University of Applied Sciences.

- "Dr.Robert E. Looney's Homepage" (PDF). Dr.Robert E. Looney.

- "Development Economics: Previous Studies".