Campus of Texas A&M University

The campus of Texas A&M University, also known as Aggieland, is situated in College Station, Texas, United States. Texas A&M is centrally located within 200 miles (320 km) of three of the 10 largest cities in the United States and 75% of the Texas and Louisiana populations. Aggieland's major roadway is State Highway 6, and several smaller state highways and Farm to Market Roads connect the area to larger highways such as Interstate 45.[1]

The campus is bisected by a set of railroad tracks primarily operated by Union Pacific Railroad.[2] The area east of the railroad tracks is known as "Main Campus"[3] and includes many of the academic buildings, the Memorial Student Center, Kyle Field, and the student dormitories. The portion of the campus west of the railroad tracks is known as "West Campus" and includes most of the other sports facilities, the business school, agricultural programs, the veterinary college, the George Bush Presidential Library and the medical school. The area of West Campus along Kimbrough Boulevard is known as "Research Park" and includes many research facilities.[4][5]

History

Establishment

The Agricultural and Mechanical College of Texas, later known as Texas A&M University was established by the Texas State Legislature on April 17, 1871 as the state's first public institution of higher education. The legislature provided $75,000 for the construction of buildings at the new school. A committee tasked with finding a home for the new college chose Brazos County, which agreed to donate 2,416 acres (10 km2) of land.[6]

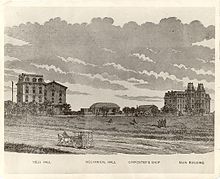

The college officially opened on October 4, 1876, with six professors. Livestock roamed freely but cautiously, and the area served as a meeting point for the Great Western Cattle Trail.[7] The first building to be placed on campus was known as Old Main. "A stately, semi-classic building four stories in height", Old Main housed all the activities of the college for the first ten years of the school's existence. In the following three decades, it played a prominent part in A&M activities and housed the offices of the school's presidents. The building caught fire in the early hours of May 27, 1912, and was unable to be saved.[8] [9]

Sul Ross era

Many people credit Texas A&M president Lawrence Sullivan Ross, known affectionately to students as "Sully", with saving the school from closure and transforming it into a respected military institution.[10] Ross, the immediate past governor of Texas, had been a well-respected Confederate soldier along with being a Baylor graduate and he enjoyed a good reputation among state residents.[6] When Ross arrived at the school in February 1891, he found that there was no running water, the school was suffering a housing shortage, the faculty was disgruntled, and many of the students ran wild.[10] Ross promptly began instituting improvements. When students returned for the 1891–1892 school year, they found a new three–story, 41 room dormitory (named Ross Hall), the beginning of construction on a new home for the president, and a new building to house the machine and blacksmith shops. Even with the addition of a new dormitory, space was still at a premium. Some cadets were forced to live on the fourth floor of the main building.[11]

Enrollment continued to rise, so much so that by the end of his tenure Ross requested that parents first communicate with his office before sending their sons to the school.[12] The increase in students necessitated an improvement in facilities, and from fall 1891 until September 1898 the college spent over $97,000 on improvements and new buildings. This included construction of an infirmary, which included the first indoor toilets on campus, a new artesian well, a natatorium, four new faculty residences, an electric light plant, an ice works, a laundry, a cold storage room, a slaughterhouse, a gymnasium, a warehouse, and an artillery shed.[13]

The last major campus construction overseen by Ross was the development of the Mess Hall. Designed by architectural firm Glover and Allen and opened in 1897, the Mess Hall could originally seat 500 students. Its front porches were later enclosed to double the seating capacity, making the Mess Hall the largest dining hall in Texas. An accidental kitchen fire on the morning of November 11, 1911, destroyed the building. Its replacement, Sbisa Dining Hall, remains one of the primary dining centers on campus.[14]

During this time one of the more recognizable features of the Texas A&M landscape, the Century Oak Tree, was planted. The massive oak tree, located in Academic Plaza, would become a favored place for students to propose marriage.[15]

Early 20th century

The focal point of campus for much of the early 20th century was Military Walk, a 1,500-foot (460 m) street that connected the former Guion Hall, now the location of the Rudder Theatre Complex, with Sbisa Dining Hall.[16] Lined with oak trees, the avenue provided access to Assembly Hall (1889–1929), Foster Hall (1899–1951), Ross Hall (1891–1955), Gaithright Hall (1876–1933), and Mitchell Hall (1912–1972). The street was closed in 1971. Many of the original trees remain, but buildings, walk ways, and grassy areas were added in place of the street itself.[citation needed]

The school began offering an expanded choice of degree programs at the same time that the state legislature and the United States Department of Agriculture established several services at Texas A&M.[6] The college was unprepared for the ensuing population growth. For the next ten years, several hundred students lived in tents in a field in the middle of campus.[17]

In the late 1920s, following the discovery of oil on university lands, Texas A&M and the University of Texas negotiated a settlement for the division of the Permanent University Fund which enabled A&M to receive one-third of the revenue. This guaranteed wealth enabled A&M to grow and expand.[6]

Post-World War II

Enrollment soared after World War II (WWII) as many former servicemen used the G.I. Bill to further their education. Again unprepared for the growth, between 1946 and 1950 Texas A&M used the inactive Bryan Air Force Base, west of Bryan near the Brazos River, as an extension of the campus. An estimated 5,500 men lived, studied, ate, and attended classes at the base, which became known as the Annex. Former students lived and studied in cramped, cheaply built and already-dilapidated WWII buildings without heating, air conditioning or indoor plumbing, and described having to hitchhike to and from the remote site if they did not have their own cars.[18]

In 1951, with the outbreak of the Korean War, the base was reactivated for United States Air Force (USAF) pilot training. In the late 1950s, after combat in Korea had wound down, the USAF inactivated the base again.[19][20] The USAF fully vacated the base in May 1961 and the land and buildings were leased to Texas A&M in 1962 under an arrangement that would allow the university to buy the property at a heavily discounted price in the future. The facility was named the Research Annex.[21]

Late 20th century

The George Bush Presidential Library was established in 1997 on 90 acres (36 ha) of land donated by Texas A&M at the western edge of the campus. This tenth presidential library was built between 1995 and 1997 and contains the presidential and vice-presidential papers of George H. W. Bush and the vice-presidential papers of Dan Quayle.[22]

In 1998, activists on campus (including Professor Patrick Slattery) suggested the statue of Lawrence Sullivan Ross should be removed on the basis that he was a member of the Ku Klux Klan.[23] Instead, Slattery and others wanted to create a "diversity plaza", with a statue of Matthew Gaines, an African-American politician.[23] The project was abandoned in the wake of the Aggie Bonfire tragedy, in 1999.[23]

The 2004 Campus Master Plan

To address the rapid growth of the student body and faculty, Texas A&M created a Campus Master plan that provided guidelines on campus development. The plan created by the architectural firm Barnes Gromatzky Kosarek Architects with Michael Dennis & Associates, was completed in July 2004. The primary goals of the plan were to: reinforce campus identity and community, establish connectivity, create architecture that contributes positively to the campus community, promote spatial equity and appropriateness, promote sustainability, and develop a supportive process to achieve the goals above.[24]

Major components of the plan include

- New Main Drive

- Administration Building/East Lawn Area

- East Quad

- East-West Pedestrian Walks

- Library Quad and Diversity Plaza

- Academic Quad and Military Walk

- Simpson Drill Field and the New Underpasses

- New West Quad and Wellborn Road

- West Campus Extension of Old Main

- White Creek Greenway

Texas A&M's master plan has won several awards including: Campus Planning Award from the Boston Society of Architects and a 2004 design award from the Texas Society of Architects.[25]

Current status

Following the completion of the master plan, Texas A&M has begun some of the largest construction projects in its history. In 2007, the Texas A&M University system had close to 700 million dollars of construction projects planned or already underway in the Bryan College Station area. To fund this expansion, the university is relying on state funding, donations, fees and tuition revenue bonds to cover costs.[26]

The first major building of this construction phase, the $95 million 220,000 square feet (20,000 m2) Interdisciplinary Life Sciences building, is the largest building on campus.[27][28] In addition, Texas A&M is constructed two physics buildings dedicated to astronomical research with funds from a donation by George P. W. Mitchell.[28] From late 2008 to August 2011, Texas A&M constructed a $104 million, Emerging Technologies and Economic Development Interdisciplinary Building.[26][29] Outside of main campus, Texas A&M Health Science Center is constructing a new campus on 200 acres (810,000 m2) in Bryan, Texas.[26] The first building on this new campus opened in 2010.[30][31] On December 16, 2010, Texas A&M broke ground on a new Humanities and Arts building. This building is especially notable because of the institution's "historical focus on engineering and agriculture".[32][33][34] The school finished renovations and reopened on the Memorial Student Center on April 21, 2012.[35]

In addition to academic facilities, athletics director Bill Byrne has overseen an aggressive expansion of the university's sports faculties since his hiring in 2003. Under his leadership, Texas A&M completed several athletics facilities including the McFerrin Athletic Center, an indoor football practice field and track and field facility. The center was host of the 2009 NCAA Indoor Championships.[36] The department has also

completed the Cox-McFerrin Center, a practice facility for the men's and women's basketball teams. The school recently renovated the schools baseball stadium, Olsen Field, with a name change to Olsen Field at Blue Bell Park following a $7 million donation from Blue Bell Creameries. The field was reopened on February 17, 2012.[37][38][39] Future plans include the renovation of Kyle field.

Areas

Main Campus

The main campus chiefly contains the student and Corps of Cadets dormitories, university apartments, various dining facilities, a health center, a post office, libraries, a university-operated golf course, and drill fields used by the Corps. The main campus houses some facilities of the College of Sciences and all of the facilities of the College of Architecture, the College of Education and Human Development, the College of Geosciences, the College of Liberal Arts, and the Dwight Look College of Engineering. Notable buildings on the main campus include Kyle Field, the Academic Building, the Memorial Student Center, the Administration Building, Rudder Tower, Albritton Bell Tower, and the Bonfire Memorial. The main campus is bordered by George Bush Drive, Wellborn Road, University Drive, and Texas Avenue on the south, west, north, and east sides, respectively.[40]

East Campus

The eastern region of campus, or "East Campus," is commonly cited as beginning to the east of Evans library and continuing to the Texas Avenue border of Texas A&M University's College Station campus. Buildings on this side of campus include the majority of architecture buildings as well as a few engineering buildings and the administration building.

West Campus

The west campus contains both the College of Veterinary Medicine and the Health Science Center, a component of the Texas A&M University System. West campus also contains some facilities of the College of Sciences, the new facilities of the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences (relocated in 2011), all of the facilities of the George Bush School of Government and Public Service, and Mays Business School. In addition to a few dining facilities, the Medical Sciences Library and the West Campus Library are the only two libraries on west campus. Olsen Field, home of the baseball team, and Reed Arena, home of the basketball team, are both situated on west campus as well. In addition, administrative offices of various state agencies, including the Texas Engineering Extension Service and Texas Transportation Institute, are housed here. Easterwood Airport, which provides flights to both George Bush Intercontinental Airport and Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport, is located on the far west side of west campus. West Campus is bordered by railroad tracks operated by Union Pacific Railroad, George Bush Drive, Raymond Stotzer Parkway, and Easterwood Airport, on the east, south, north, and west sides, respectively.[40]

RELLIS Campus

Formerly named the Research Annex, the Research and Extension Center at Bryan, and then the Riverside Campus, and commonly known as the Riverside Annex or simply the Annex, the RELLIS Campus is an extension of the main campus located 10 miles (16 km) to the northwest, adjacent to SH 47 and SH 21 in Bryan, Texas, northeast of the Brazos River. It is home to a Blinn College satellite campus.

SH 47 was completed in August 1996, creating a shorter and more direct route between the facility and the main A&M campus.[41]

In 2016, the facility was renamed RELLIS - an acronym of Texas A&M’s core values of respect, excellence, leadership, loyalty, integrity and selfless service.[42]

The 1,900-acre (8 km2) RELLIS hosts three training divisions of the Texas Engineering Extension Service (TEEX), which occupies about 100,000 square feet (10,000 m2) of offices, classrooms, and laboratories. The agency maintains outdoor training facilities at Riverside, including overhead and underground electric power training fields, a firing range for law enforcement officers, a heavy equipment training field, an emergency vehicle-driving track, unexploded ordnance ranges and search grids, and simulation prop houses for tactical training.[43][44]

A vintage WWII hangar at the RELLIS Campus was recently[timeframe?] transformed into a state-of-the-art training facility for utility workers in the electric power and telecommunications industry. Classrooms in the new facility include interactive Smart boards, custom-built workbenches and cabinets, built-in audiovisual systems, and automatic lighting.[citation needed]

The runways have also been used as an SCCA racetrack.[45][better source needed]

In 2006, the Texas A&M College of Architecture completed an 8,000-square-foot (700 m2) Built Environment Teaching and Research Facility also known as Architecture Ranch.[46] The building contains a woodshop, a metal shop, and two digital fabrication machines: a CNC mill and a CNC plasma cutter. Architecture Ranch is located on 12 acres (4.9 ha).[47]

The campus is also home to several Texas Transportation Institute (TTI) testing facilities used in the areas of vehicle performance and handling, vehicle-roadway interaction, the durability and efficacy of highway pavements, and the safety of structural systems.[48]

A joint Texas A&M System-University of Texas system low density library began construction in June 2012. The facility is designed to hold one million books and eliminate redundancy in the collections of the two university systems.[49]

In 2015, Blinn College announced that it would cancel expansion plans at its existing Bryan campus and build a new campus at RELLIS instead.[50] Blinn expected to invest $34 million in the site.[51] The groundbreaking ceremony for the Blinn College educational building took place on March 31, 2017.[52] In 2022, Blinn opened a new $32M administration building at RELLIS, incorporating 19 new classrooms in addition to offices for student enrollment.[53]

Bush Combat Development Complex

The George H.W. Bush Combat Development Complex is a military research center on the RELLIS Campus, part of the United States Army Futures Command. The $200M facility was first announced in August 2019, and opened in 2022. It includes a "one-of-a-kind, kilometer-long tunnel" used for hypersonic research.[54] The complex is also home to the Research Integration Center; Innovation Proving Ground; and Ballistic, Aero-optics and Materials Range, where weapons are tested. Raytheon tested a high-energy laser test there in 2023, the first open-air usage in the state of Texas. The facility was initially funded by the state of Texas ($50M), Texas A&M ($80M) and the AFC ($96M).[55]

Retired USAF Maj. Gen. Tim Green serves as Director of the site,[56] and retired Army Col. Rosendo “Ross” Guieb serves as Executive Director.[57]

Residential life

During the 2006 fall semester, 20.5% of the student body lived on campus in one of two distinct housing sections located on opposite ends of campus.[58] Both the Northside and Southside areas contain student dormitories, or residence halls. While some halls are single-sex, others are co-educational. Usually students of different genders live on alternate floors, although the Corps dormitories and Hobby Hall are segregated by room or suite.[59] Residence hall styles vary; while many halls offer only indoor access to individual rooms, access to the rooms of "balcony halls", comes from an outdoor balcony. Room sizes vary by building, and halls with larger rooms including en-suite or private bathrooms, while halls with smaller rooms have a common bathroom on each floor. Several halls include a "substance-free" floor, where residents pledge to avoid bringing alcohol, drugs, or cigarettes into the hall.[60] While the university provides a variety of dining facilities, non-Corps students are not required to purchase a meal plan.[61]

Northside consists of 17 student residence halls, including the three university honors dorms.[62] The halls are located near Northgate, a local entertainment district. The campus dining establishments Sbisa Dining Hall and The Underground are located on Northside. Some halls have unofficially claimed tables within the Sbisa Dining Hall and many halls congregate for dinner at a specific time each weekday.[63]

Southside contains halls both for the Corps of Cadets members and "non-regs". Non-corps halls in this area center around the Commons, a hub for activities and dining.[64] Southside has two Learning Living Communities, which allow freshmen to live in a cluster with other students who share common interests.[65]

Facilities for the Corps of Cadets are located in the Quadrangle, or "The Quad", an area consisting of dormitories, Duncan Dining Hall, and the Corps training fields.[66] The Corps Arches, a series of 12 arches that "[symbolize] the undying spirit of the 12th Man of Texas A&M", mark the entrance to the Quadrangle.[67] All cadets, except those who are married or who have had previous military service, must live in the Quad with assigned roommates from the same unit and graduating class. Reveille, the Aggie mascot, lives with her handlers in the Quadrangle.[68]

Married students, single parent students, and undergraduate students who are sophomores, juniors, or seniors and do not have children may live in the Gardens at University Apartments.[69] This complex is, as of 2011, Texas A&M's newest apartment unit complex.[70] Gardens at University Apartments is zoned to the College Station Independent School District, which educates dependent children who live in them.[71] Residents are zoned to College Hills Elementary School,[72] Oakwood Intermediate School, A&M Consolidated Middle School, and A&M Consolidated High School.[73]

White Creek Apartments has all categories of single, unmarried students.[69]

Married students and students with families as well as sophomore and higher undergraduate students previously lived at Avenue A Apartments, College View Apartments, and Hensel Apartments.[74] Texas A&M University has announced that all residents must be moved out of the Avenue A Apartments, College View Apartments, and Hensel Apartments by 5pm on May 31, 2013. Afterwards, the aforementioned apartments will be demolished in preparation for the Campus Point project.[75]

In 1998 American Campus Communities was awarded the contract to develop, build, and manage a student housing property at TAMU.[76]

The Aggies also have many opportunities to not only clean up their campus, but also help in the surrounding community. Students pick up trash and recyclables in Galveston State Park, along nearby highways, and after every home football game.[77][78][79]

Notable buildings

Of the over 200 buildings on the Texas A&M University campus, the most recognized include the Academic Building, Albritton Bell Tower, the O&M Building, the Administration Building, the George Bush Presidential Library, Kyle Field, and the Memorial Student Center (MSC).

Academic Building

The Academic Building stands at the crossroads of the campus. Completed in 1914, it stands on the site of Old Main, the first campus building, which burned to the ground in 1912. Its most prominent feature is its copper dome, which is green with verdigris, much like the Statue of Liberty. When the building was constructed, it was one of the first on campus to use rebar. Its architect, A&M Professor F. E. Giesecke knew little about reinforced concrete, "so [he] just figured out the amount of steel...necessary and doubled it". The result was an extremely durable building so filled with steel that blowtorches had to be used when piping for water fountains was added. In front of the Academic Building is the Academic Plaza, which is the site of a wide range of campus events, most notably Silver Taps.[80][81]

Albritton Bell Tower

Donated to Texas A&M University by Martha and Ford D. Albritton and dedicated on October 6, 1984, the Albritton Tower is 138 feet (42 m) tall and contains 49 bells, cast by the Paccard Bell Foundry, weighing a total of 17 short tons (34,000 lb; 15,000 kg), the largest of which weighs 6,500 pounds (2,900 kg). The bells ring every quarter-hour and are also programmed to play music such as The Spirit of Aggieland, patriotic songs, and hymns.[82][83]

Eller O&M Building

The David G. Eller Oceanography & Meteorology (O&M) Building is the tallest building at Texas A&M University. The construction of the Oceanography and Meteorology (O&M) building began in August 1970 and was completed in 1973. The architectural designers for the building were the father and son team of Preston M. Geren Sr. and Preston M. Geren Jr. of Fort Worth. Both the Gerens are Aggies. The building was built by the Tulsa, OK-based Manhattan Construction Company. It cost $7.6 million to build and was constructed of reinforced concrete and steel, with limestone exterior walls. In 1989, the building was renamed the David G. Eller Building for Oceanography and Meteorology, after David G. Eller, the former Chairman of the University Board of Regents.[84]

The building encompasses 109,609 square feet (10,183 m2) of office, classroom, laboratory, and storage space. Housing the departments of geography, atmospheric sciences, and oceanography, it maintains a TTVN site for distance education which facilitates teaching with the Texas A&M University at Galveston campus. A Doppler radar system located on the roof provides data on severe storms.[85]

E.V. Adams Band Hall

The E.V. Adams Band Hall houses the Texas A&M Wind Symphony, the Fightin' Texas Aggie Band, as well as the University Symphonic, Concert, and Jazz Band; and Orchestra. Constructed in the 1970s, the Adams band hall was initially intended to serve as a dormitory office building. It is a two-story building with a basement. The Music Programs were moved out and into a new multimillion-dollar facility (The John D. White '70 - Robert L. Walker '58 Music Activities Center) in the Fall of 2019, it includes an indoor marching hall design for the Fightin' Texas Aggie Band and a two Smaller Halls for the Concert Bands, Orchestras, and Choirs as well as numerous well insulated individual practice room. . On Top of that facing toward Kyle field is a full sized Practice Turf field for the Aggie Band.

The George Bush Presidential Library and Museum

The George Bush Presidential Library and Museum is located on a 90-acre (36 ha) site on west campus. The Library and Museum is situated on a plaza adjoining the Presidential Conference Center and the Texas A&M Academic Center. It operates under the administration of the NARA under the provisions of the Presidential Libraries Act of 1955.

The archives contains over 38 million pages of personal papers and official documents from the Vice Presidency and Presidency as well as personal records from associates connected with President Bush's public career as congressman, Ambassador to the United Nations, Chief of the U.S. Liaison Office in China, Chairman of the Republican National Committee, and Director of the Central Intelligence Agency. In addition to memoranda, speeches, and reports found in the textual collection, there is an extensive audiovisual and photographic archive that includes approximately one million photographs and thousands of hours of audio and video tape.

The 1997 statue, The Day the Wall Came Down, is exhibited on the Library grounds.

Jack K. Williams Administration Building

The Administration Building is the centerpiece of the main entrance to Texas A&M University. For many years home to all of Texas A&M's administrative offices, the Jack K. Williams Administration Building opened its doors in 1932. It continues to house several Texas A&M University and Texas A&M University System offices and agencies. Designed by Professor C.S.P. Vosper and built by Campus Architect F.E. Giesecke, features of this monumental classical structure include intricate Ionic columns, polished brass handrails along its marble staircases and stained-glass windows. In 1997, the building was officially named after former Texas A&M University president Jack Williams to honor his work in increasing enrollment while preserving the traditional aura of the campus.[86][87]

Kyle Field

One of the most prominent architectural features of the campus is the Kyle Field, also known as The Home of the 12th Man. In the fall of 1904, Edwin Jackson Kyle, professor of horticulture and an 1899 graduate of Texas A&M, fenced off a section of the southeast corner of campus that had been assigned to him for agricultural use. Using $650 of his own money, he purchased the covered grandstand from the Bryan fairgrounds and built wooden bleachers to raise the seating capacity to 500 people.[88][89] After the first World War, the stadium was dedicated as a living memorial to the Aggies who died in that conflict. On game days 55 American flags, one for each Aggie killed, fly around the highest points of the stadium.[90] At Kyle Field, the November 1921 game between the Aggies and their long-time rival, the University of Texas, became the first college football game to offer a live, play-by-play broadcast.[91]

Over the years, the modest wooden bleachers were expanded to a three deck concrete stadium with a capacity of 83,002, the second largest football venue in Texas.[92] The largest stadium in the state previously belonged to the University of Texas. Other features of the stadium and surrounding area include the Bright Football Complex, a natural grass field,[93] the Texas A&M Sports Museum, a press box, and the second largest video board in college athletics.[94] Kyle Field is often regarded as one of the most intimidating college football stadiums in the nation. CBS Sportsline listed Kyle Field as the nation's top stadiums with a top-ranked score in three categories (atmosphere, tradition, and fans).[95]

Memorial Student Center

Popularly known as "The Living Room of Texas A&M", the Memorial Student Center (MSC) has been a living memorial, a living room, and a living tradition at Texas A&M University. Dedicated on Muster Day (April 21) in 1951, the MSC was originally dedicated to those Aggies who gave their lives during World Wars I and II, but was later rededicated to all Aggies who have given or will give their lives in wartime.[96] Because the building and grounds are a memorial, those entering the MSC are asked to "uncover" (remove their hats) and not walk on the surrounding grass lawns.[97]

On the main floor of the MSC is the Flagroom, a large, flag-lined room which students use for meetings, visiting, napping, and studying. The MSC also contains a bookstore, a bank, three art galleries, three dining facilities, and two ballrooms, one of which named after Robert Gates. Additionally, the MSC contains many meeting rooms and is the home of numerous student committees "that provide an array of educational, cultural, recreational and entertainment programs for the Texas A&M community."[96]

In 2007, the Aggie student body voted for $122 million renovations to the Memorial Student Center, allowing it to become fully compliant with both fire code and the Americans with Disabilities Act. The project began in the summer of 2009, requiring the building to remain closed due to the renovations.[98] The renovations increased the size of the building to accommodate the growing school population, and make more efficient use of existing space.[99][100] The MSC reopened on Muster Day, April 21, 2012, 61 years after its original opening.

Transportation

On-campus residents, who make up about 20% of the student body, usually travel to classes by walking, biking, or taking the on-campus shuttle.[58] Faculty, staff, and visitors may also take advantage of the on-campus shuttle route system, which operates from 7 am to 6 pm on weekdays, and at select times during nights and weekends.[101][102] Sidewalks and walkways pervade the campus to allow pedestrians to travel to their selected destination. Multiple bike racks are located throughout the campus, especially adjacent to buildings, for bicyclists to park their bicycles.[103]

Off-campus residents, who make up the remaining 80% of the student body, may travel to campus by walking, bicycling, driving by motor vehicle, or taking the off-campus shuttle.[58] Students who reside in the Northgate area usually walk or bike to campus due to its close proximity. Those who travel to campus by an automobile park on assigned student parking lots located throughout the campus and travel to their classes by walking or taking the on-campus shuttle. Motorcycle parking lots are also located throughout the campus for motorcyclists.[104] As the on-campus shuttle route, the off-campus route operates 7 am to 6 pm on weekdays, and at select times on nights and weekends.[102][105]

Other facilities

The main campus of the university includes two branch campuses of the main campus: Texas A&M at Qatar located in Education City in Doha, Qatar devoted to engineering disciplines[106] and Texas A&M University at Galveston in Galveston, Texas, devoted to marine research and host to the Texas Maritime Academy.[107] It also includes three international facilities, a multipurpose center in Mexico City, Mexico, the Santa Chiara Study Abroad Center in Castiglion Fiorentino, Italy shared with Kansas State University and the University of Colorado[108] and the Soltis Center for Research and Education in Costa Rica. On August 12, 2013 the university purchased the Texas Wesleyan University School of Law and renamed it the Texas A&M School of Law. Texas A&M on October 23, 2013 announced plans to build a new branch campus, Texas A&M University at Nazareth - Peace Campus, in Israel.[109]

Texas A&M University has expanded in 2013 with the merging of the Texas A&M Health Science Center, and the acquisition of Texas Wesleyan University School of Law.

Texas A&M Health Science Center

The Texas A&M Health Science center was merged with Texas A&M on July 12, 2013. The Texas A&M Health Science Center offers programs on a "distributed" (geographically dispersed) model, with two simulation centers for practice learning. It has six academic colleges in different places across Texas:

- the Texas A&M University College of Dentistry at Dallas

- the College of Medicine campuses at Bryan, Temple and Round Rock

- the Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences campuses at College Station, Temple and Houston

- the School of Rural Public Health at College Station

- the Irma Lerma Rangel College of Pharmacy at Kingsville

- the College of Nursing in Bryan, Texas and Round Rock

Other components include the Institute of Biosciences and Technology at Houston and the Coastal Bend Health Education Center.

Texas A&M School of Law

On June 26, 2012, Texas Wesleyan University and Texas A&M University reached an agreement whereby Texas A&M would take over ownership and operational control of the School, to be renamed The Texas A&M University School of Law.[110] The agreement was finalized on August 12, 2013. Texas A&M purchased the school, the land, and everything with it for $73 million.

Footnotes

- ^ "Bryan-College Station: Quick Facts". Bryan-College Station (Texas) Chamber of Commerce. Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved April 18, 2007.

- ^ Jackson, Luke (October 1, 2004). "Union Pacific, A&M, CS officials agree to slow trains". The Battalion. Archived from the original on May 1, 2005. Retrieved April 18, 2007.

- ^ "FREE ON-CAMPUS BUS SERVICE OFFERED AT TEXAS A&M UNIVERSITY" (Press release). Texas A&M University. September 6, 1996. Archived from the original on September 17, 2009. Retrieved June 23, 2008.

- ^ "The Campus in 2020: Connect East and West Campus". Texas A&M University. Archived from the original on October 16, 2007. Retrieved 2007-04-18.

- ^ "Texas A&M Campus Map Center". Texas A&M University. Archived from the original on March 10, 2009. Retrieved February 17, 2009.

- ^ a b c d "Texas A&M University". The Handbook of Texas. Archived from the original on December 3, 2010. Retrieved March 22, 2007.

- ^ Dethloff, Henry C. (1975). A Pictorial History of Texas A&M University, 1876–1976. College Station, Texas: Texas A&M University Press. pp. 16–17.

- ^ ""Old Main": A Visual Record of a Building's Life and Passing". The Texas Aggie. March 1994. Archived from the original on December 15, 2012. Retrieved April 30, 2007.

- ^ Chapman, David L. (March 1995). "Gaithright Hall: A Magnificent Afterthought". The Texas Aggie. Archived from the original on December 15, 2012. Retrieved April 30, 2007.

- ^ a b Ferrell, Christopher (2001). "Ross Elevated College from "Reform School"". The Bryan-College Station Eagle. Archived from the original on October 16, 2007. Retrieved June 23, 2008.

- ^ Benner (1983), p. 206.

- ^ Benner (1983), p. 218.

- ^ Benner (1983), p. 219.

- ^ Chapman, David L. (October 1995). "Texas A&M's castle: The Old Mess Hall (1897–1911)". The Texas Aggie. Archived from the original on December 12, 2012. Retrieved April 30, 2007.

- ^ Orton, Megan (July 28, 2003). "Urban forester maintains AM landscape". The Battalion. College Station, Texas. Archived from the original on September 29, 2007.

- ^ "Military Walk — A Texas A&M Tradition Restored By Grad Dan A. Hughes". Texas A&M Today. Texas A&M. September 8, 2010. Archived from the original on May 2, 2018. Retrieved May 1, 2018.

Military Walk, which is approximately 1,500 feet long, is the North-South axis of the campus, linking the Sbisa Dining Hall area to the Rudder/Memorial Student Center complex in the heart of the campus.

- ^ Liffick, Brandie (October 30, 2001). "Tradition spanning generations". The Battalion. Archived from the original on September 29, 2007. Retrieved 2007-03-22.

- ^ Gillentine, Kristy (March 11, 2007). "Aggies recall days at Annex". The Bryan-College Station Eagle. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved June 23, 2008.

- ^ Leatherwood, Art (November 1, 1994). "Bryan Air Force Base". Retrieved August 21, 2024.

- ^ "Bryan Air Force Base". rellisrecollections.org. Retrieved August 21, 2024.

- ^ "Research Annex". rellisrecollections.org. Retrieved August 21, 2024.

- ^ Alsobrook, David E. "The Birth of the Tenth Presidential Library: The Bush Presidential Materials Project, 1993–1994". George Bush Presidential Library. Archived from the original on August 7, 2007. Retrieved March 22, 2007.

- ^ a b c Slattery, Patrick (2006). "Deconstructing Racism One Statue at a Time: Visual Culture Wars at Texas A&M University and the University of Texas at Austin". Visual Arts Research. 32 (2): 28–31. JSTOR 20715415.

- ^ Barnes Gromatzky Kosarek Architects with Michael Dennis & Associates (2004). "Campus Master Plan" (PDF). Texas A&M University. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 20, 2008. Retrieved 2008-01-06.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Meyers, Rhiannon (August 31, 2004). "Campus master plan wins design awards". The Battalion. Archived from the original on August 12, 2007. Retrieved August 31, 2006.

- ^ a b c Huffman, Holly (June 17, 2007). "A&M construction projects add to $700 million". The Eagle. Archived from the original on May 29, 2011. Retrieved March 18, 2009.

- ^ "Ground Broken for ILSB". Texas A&M University. May 30, 2006. Archived from the original on July 27, 2007. Retrieved January 6, 2008.

- ^ a b Watkins, Matthew (May 2, 2006). "Construction slated for A&M". The Battalion.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Watts, Rebecca (January 1, 2009). "Engineering and Applied Technologies Align". AbouTown Press. p. 49. Archived from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved March 18, 2009.

- ^ "Texas A&M Health Science Center, City of Bryan raise flags on new campus" (Press release). City of Bryan. November 5, 2008. Archived from the original on May 27, 2010. Retrieved 2009-03-18.

- ^ Maier, Scott (July 22, 2010). "TAMHSC dedicates Bryan campus". Texas A&M Health Science center. Archived from the original on January 19, 2011. Retrieved December 31, 2010.

- ^ Patel, Vimal (October 28, 2009). "A&M Acts on Arts Building". The Eagle. Archived from the original on June 15, 2011. Retrieved December 31, 2010.

- ^ "New Texas A&M Arts & Humanities Building". Spirit and Mind. Texas A&M University. Archived from the original on January 1, 2011. Retrieved December 31, 2010.

- ^ "Updated: 3:53 PM Oct 27, 2009 New Texas A&M Building Dedicated To Arts And Humanities Announced". KBTX. October 27, 2010. Archived from the original on December 8, 2010. Retrieved December 31, 2010.

- ^ Dror, Michael (September 21, 2011). "MSC Renovations to Honor the Past". The Battalion. Archived from the original on June 14, 2012. Retrieved October 2, 2011.

- ^ Lee, Kirby (March 14, 2009). "Former allies friendly rivals". Press-Telegram. Archived from the original on June 13, 2011. Retrieved 2009-03-18.

- ^ Cox, Brad (January 30, 2009). "Olsen Field renovation process moves on". The Battalion. Retrieved February 7, 2009.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Zwerneman, Brent (January 28, 2009). "A&M's Olsen Field in line for extreme makeover". Houston Chronicle. Archived from the original on May 22, 2011. Retrieved February 7, 2009.

- ^ McAuliffe, Shane (May 7, 2011). "Olsen Field Officially Starts $24 Million Renovation". KBTX.com. Archived from the original on June 11, 2011. Retrieved June 16, 2011.

- ^ a b "Texas A&M Campus Map Project". Texas A&M University Division of Marketing and Communications. Archived from the original on November 2, 2007. Retrieved May 16, 2007.

- ^ "Innovation Corridor - City of Bryan". City of Bryan. Retrieved August 20, 2024.

- ^ "Texas A&M announces plans to expand Riverside campus". The Eagle. The Eagle. May 2, 2016. Retrieved June 25, 2017.

- ^ "Riverside Campus-Texas A&M University". Texas A&M University. Archived from the original on February 17, 2007. Retrieved 2007-05-16.

- ^ Texas Engineering Extension Service website Archived May 18, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ North American Motorsports Archived September 4, 2012, at archive.today

- ^ College of Architecture Newsletter Fall 2006 Archived July 31, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ College of Architecture Archived July 25, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Riverside Campus". Texas A&M University. Archived from the original on May 9, 2007. Retrieved 2007-05-16.

- ^ Stephenson, Lane (May 4, 2012). "Construction of Joint Texas A&M-UT System Library Facility To Begin in June". TAMU Times. Archived from the original on May 14, 2012. Retrieved May 13, 2012.

- ^ "Blinn halts construction on new Bryan campus; will build on A&M's RELLIS Campus". KAGS-LD. Bryan, Texas. May 31, 2016. Retrieved August 21, 2024.

- ^ Kuhlmann, Steve (December 15, 2016). "Blinn approves construction deal for RELLIS facility". Bryan-College Station Eagle. Retrieved February 21, 2017.

- ^ Kuhlmann, Steve (April 1, 2017). "Blinn College breaks ground on RELLIS expansion". The Bryan-College Station Eagle. Retrieved April 2, 2017.

- ^ Oliver, Bill (August 17, 2022). "Public Is Invited To Friday's Grand Opening Of The Blinn College RELLIS Campus Administration Building". WTAW (AM). College Station, Texas. Retrieved August 21, 2024.

- ^ "Texas A&M System Regents Approve RELLIS To Be Army Futures Command Central Testing Hub". Texas A&M University System. July 8, 2019. Retrieved July 9, 2019.

- ^ Alex Miller (November 3, 2023). "Bush Combat Development Complex officials look forward to what's next". The Eagle. Retrieved July 11, 2024.

- ^ Pappalardo, Joe (November 9, 2022). "Inside Texas A&M's New Military Combat Lab". Texas Monthly. Retrieved August 28, 2024.

- ^ Carlson, Kara. "Goal is finding tech to 'deter war,' says new leader for Texas A&M Army test center". Austin-American Statesman. Retrieved August 28, 2024.

- ^ a b c "Texas A&M University Fall 2006 Enrollment" (PDF). Texas A&M University. pp. 7–8. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 14, 2007. Retrieved 2007-02-25.

- ^ Womack, Stuart (August 23, 2006). "Dorms Go Through Changes". The Battalion. Archived from the original on September 29, 2007. Retrieved 2007-04-30.

- ^ "A New Place to Hang Your Hat". The Battalion. September 2, 2002. Archived from the original on February 3, 2013. Retrieved April 30, 2007.

- ^ "Dining Services: FAQ". Texas A&M University Dining Services. 2007. Archived from the original on February 10, 2007. Retrieved April 30, 2007.

- ^ "Northside Halls". Texas A&M University. 2007. Archived from the original on May 22, 2007. Retrieved 2007-04-30.

- ^ Hixson, Josh (February 1, 2006). "Dorm Wars". The Battalion. Archived from the original on February 4, 2013. Retrieved April 30, 2007.

- ^ "Residence Halls by Style – Commons". Texas A&M University. 2007. Archived from the original on May 4, 2007. Retrieved 2007-04-30.

- ^ "Leadership Living Learning Communities". Texas A&M University Department of Residence Life. Archived from the original on June 8, 2007. Retrieved 2007-05-22.

- ^ "Cadet Resident Handbook". Texas A&M University. May 2006. Archived from the original on April 26, 2007. Retrieved 2007-04-30.

- ^ "Visiting Campus: Texas A&M University Corps of Cadets". Texas A&M University Corps of Cadets. Archived from the original on July 23, 2007. Retrieved 2007-04-30.

- ^ "Cadet Resident Handbook". Texas A&M University Corps of Cadets. Archived from the original on April 26, 2007. Retrieved 2007-04-30.

- ^ a b "Apartments Archived December 21, 2016, at the Wayback Machine." Texas A&M University. Retrieved on December 15, 2016.

- ^ "The Gardens at University Apartments Archived March 5, 2012, at the Wayback Machine." Texas A&M University. Retrieved October 3, 2011.

- ^ "Apartments Map Archived June 7, 2015, at the Wayback Machine." Texas A&M University via Google Maps. Retrieved October 2, 2011.

- ^ "New_El_Zone_Map.pdf Archived November 11, 2011, at the Wayback Machine." College Station Independent School District. Retrieved October 2, 2011.

- ^ "New_Sec_Zone_Map.pdf Archived December 1, 2010, at the Wayback Machine." College Station Independent School District. Retrieved October 2, 2011.

- ^ "Apartment Information Archived November 2, 2011, at the Wayback Machine." Texas A&M University. Retrieved October 3, 2011.

- ^ "Campus Point information." Texas A&M University. Retrieved April 27, 2013.

- ^ "COMPANY NEWS." Austin American-Statesman. June 27, 1998. D6. Retrieved October 5, 2011. "American Campus Communities has been awarded projects totaling $52.5 million to develop, build and manage three student housing projects at Prairie View A&M University, Texas A&M University and Iona College."

- ^ "Aggies Go Green". Archived from the original on July 23, 2009. Retrieved June 5, 2009.

- ^ "Environmental Issues Committee". Archived from the original on April 16, 2009. Retrieved June 5, 2009.

- ^ "The College Sustainability Report Card". Archived from the original on June 15, 2009. Retrieved June 5, 2009.

- ^ Chapman, David L. "A Symbol of Academic Excellence: The Academic Building". Cushing Memorial Library and Archives, Texas A&M University. Archived from the original on December 11, 2012. Retrieved May 12, 2007.

- ^ "Academic Building". Texas A&M University. Archived from the original on May 2, 2007. Retrieved April 21, 2007.

- ^ "Albritton Bell Tower". Emporis.com. Archived from the original on February 15, 2013. Retrieved June 22, 2008.

- ^ Boyle, Andy (October 1, 2007). "Campus bell tower donated by 1898 UNL almunus". Daily Nebraskan. Archived from the original on August 9, 2011. Retrieved June 22, 2008.

- ^ "TAMSCAMS: Department History, Page 2". Texas A&M Student Chapter of the American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on March 10, 2007.

- ^ "College of Geosciences – Facilities". Texas A&M University College of Geosciences. Archived from the original on March 10, 2007.

- ^ "Jack K. Williams Honored With Building Dedication". Texas A&M University. April 25, 1998. Archived from the original on July 14, 2012. Retrieved June 23, 2008.

- ^ "Jack K. Williams Administration Building". Texas A&M University. Archived from the original on March 4, 2005. Retrieved April 21, 2007.

- ^ Perry, George Sessions (1951). "The Story of Texas A&M". McGraw-Hill.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Dethloff, Henry C. (1975). A Centennial History of Texas A&M University, 1876–1976. Texas A&M University Press. p. 505.

- ^ "The Standard" (PDF). Company D-2, Texas A&M Corps of Cadets. p. F–55. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 11, 2006. Retrieved February 28, 2007.

- ^ Schultz, Charles R. "First Play-by-Play Radio Broadcast of a College Football Game". WTAW. Archived from the original on November 11, 2006. Retrieved May 8, 2007.

- ^ "Kyle Field". Official Website of Texas A&M Athletics. Archived from the original on August 23, 2006. Retrieved September 27, 2006.

- ^ "Kyle Field's turf the "13th man"?". Sports Turf. 2004. Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved February 28, 2007.

- ^ "Lights, Camera, Action: Introducing 12th Man TV". Official Website of Texas A&M Athletics. Archived from the original on September 18, 2006. Retrieved September 27, 2006.

- ^ Dodd, Dennis (2007). "Top 25 College Football Stadiums". CBS Sportsline. Archived from the original on March 10, 2007. Retrieved 2007-04-30.

- ^ a b "A Living Memorial". Texas A&M University. Archived from the original on August 25, 2004. Retrieved April 30, 2007.

- ^ "Memorial Student Center - Aggie Traditions". Texas A&M.

- ^ "MSC closing for renovations". Archived from the original on June 14, 2012.

- ^ "Project Cost". Texas A&M MSC renovations. Texas A&M University. Archived from the original on October 12, 2007. Retrieved 2008-01-23.

- ^ "MSC project detailed". Archived from the original on September 12, 2012.

- ^ "On-Campus Routes". Texas A&M University Transportation Services. Archived from the original on May 19, 2007. Retrieved May 16, 2007.

- ^ a b "Transit Service". Texas A&M University Transportation Services. Archived from the original on May 22, 2008. Retrieved June 23, 2008.

- ^ "Texas A&M University Bike Rack Locations" (PDF). Texas A&M University Transportation Services. Retrieved May 16, 2007.

- ^ "Texas A&M University Campus Parking" (PDF). Texas A&M University Transportation Services. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 6, 2006. Retrieved May 17, 2007.

- ^ "Off-Campus Routes". Texas A&M University Transportation Services. Archived from the original on May 19, 2007. Retrieved 2007-05-17.

- ^ "Texas A&M University at Qatar". Texas A&M University. Archived from the original on May 3, 2007. Retrieved April 30, 2007.

- ^ "Texas A&M University at Galveston". The Handbook of Texas. Archived from the original on July 15, 2011. Retrieved May 22, 2007.

- ^ "International Programs Office". Texas A&M University. Archived from the original on May 10, 2007. Retrieved May 22, 2007.

- ^ Garrett, Robert (October 23, 2013). "Rick Perry visits Israel, touts new Texas A&M campus". Dallas Morning News. Archived from the original on October 27, 2013. Retrieved October 25, 2013.

- ^ "Texas Wesleyan School of Law". JO. Archived from the original on October 3, 2015. Retrieved January 27, 2015.

References

- Benner, Judith Ann (1983). Sul Ross, Soldier, Statesman, Educator. College Station, Texas: Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 978-0-89096-142-1.