QF 3-inch 20 cwt

| QF 3 inch 20 cwt anti-aircraft gun | |

|---|---|

Aboard HMS Royal Oak in World War I | |

| Type | Anti-aircraft gun |

| Place of origin | United Kingdom |

| Service history | |

| In service | 1914–1947[1] |

| Used by | United Kingdom Australia Canada Finland Ireland |

| Wars | World War I World War II |

| Production history | |

| Designer | Vickers |

| Variants | Mk I, Mk I*, Mk IB, Mk 1C, Mk 1C*, Mk IE, Mk SIE, Mk II, Mk III, Mk IV, Mk IVA[2] |

| Specifications | |

| Mass | 2,240 lb (1,020 kg), gun and breech 5.99 tons,[3] with 2-wheel platform |

| Barrel length | Bore: 11 ft 4 in (3.45 m) (45 cal) Total: 11 ft 9 in (3.58 m)[3] |

| Crew | 11[4] |

| Shell | Fixed QF HE 76.2 × 420 mm R[5][6] |

| Shell weight | 12.5 lb (5.7 kg), 1914; 16 lb (7.3 kg), 1916 |

| Calibre | 3 inches (76 mm) |

| Breech | Semi-automatic sliding-block[7] |

| Recoil | 11 inches (280 mm). hydro spring, constant[3] |

| Carriage | High-angle wheeled, static, or lorry mounting |

| Elevation | −10 – 90°[3] |

| Traverse | 360° |

| Rate of fire | 16–18 rpm[8] |

| Muzzle velocity | 2,500 ft/s (760 m/s), 12.5 lb (5.7 kg) shell 2,000 ft/s (610 m/s), 16 lb (7.3 kg) shell[9] |

| Effective firing range | 16,000 ft (4,900 m)[8] |

| Maximum firing range | 23,500 ft (7,200 m), 12.5 lb shell[3] 22,000 ft (6,700 m), 16 lb shell[8] |

The QF 3-inch 20 cwt anti-aircraft gun became the standard anti-aircraft gun used in the home defence of the United Kingdom against German Zeppelins airships and bombers and on the Western Front in World War I. It was also common on British warships in World War I and submarines in World War II. 20 cwt referred to the weight of the barrel and breech, to differentiate it from other 3-inch guns (1 cwt = 1 hundredweight = 112 lb, 51 kg, hence the barrel and breech together weighed 2,240 lb, 1,020 kg). While other AA guns also had a bore of 3 inches (76 mm), the term 3-inch was only ever used to identify this gun in the World War I era, and hence this is what writers are usually referring to by 3-inch AA gun.

Design and development

The gun was based on a prewar Vickers naval 3-inch (76 mm) QF gun with modifications specified by the War Office in 1914. These (Mk I) included the introduction of a vertical sliding breech-block to allow semi-automatic operation. When the gun recoiled and ran forward after firing, the motion also opened the breech, ejected the empty cartridge case and held the breech open ready to reload, with the striker cocked. When the gunner loaded the next round, the block closed and the gun fired.[7]

The early 12.5-pound (5.7 kg) shrapnel shell at 2,500 ft/s (760 m/s) caused excessive barrel wear and was unstable in flight. The 1916 16-pound (7.3 kg) shell at 2,000 ft/s (610 m/s) proved ballistically superior and was better suited to a high explosive filling.[8]

The Mark I* had different rifling. The Mark II lost the semi-automatic action. The Mk III of 1916 reverted to a 2-motion screw breech to suit available manufacturing capability, and Mk IV had a single-tube barrel and single-motion screw breech;[1] a Welin breech block with an Asbury breech.[10]

A US Army report on anti-aircraft guns of April 1917 reported that this gun's semi-automatic loading system was discontinued because of difficulties of operation at higher angles of elevation, and replaced by "the standard Vickers-type straight-pull breech mechanism", reducing rate of fire from 22 to 20 rds/minute.[11] Routledge quotes a rate of fire of 16–18 rounds per minute, in the context of the 16-pounder shell of 1916.[8] This would appear to be the effective rate of fire found to be sustainable in action.

Beginning in 1930, a new towed 4-wheeled sprung trailer platform on pneumatic tyres was introduced to replace the obsolete lorries and two-wheeled carriages still used as mounts from World War I, barrels were equipped with loose liners, and the guns were connected to the new Vickers No. 1 Predictor.[12][13] Eight more Mks followed between the World Wars.[1] By 1934 the rocking-bar deflection sights had been replaced by Magslip receiver dials which received input from the Predictor, with the layers matching pointers instead of tracking the target.[14] Predictor No. 1 was supplemented from 1937 by Predictor No. 2, based on a US Sperry AAA Computer M3A3. This was faster and could track targets at 400 mph (640 km/h) at heights of 25,000 ft (7,600 m), both Predictors received height data, generally from the Barr & Stroud UB 7 (9-foot base) instrument.[15]

The 3-inch 20 cwt gun was superseded by the QF 3.7-inch (94 mm) AA gun from 1938 onwards, but numbers of various Marks remained in service throughout World War II. In Naval use it was being replaced in the 1920s by the QF 4-inch (100 mm) Mk V on HA (high-angle) mounting.

Combat use

World War I

Britain entered World War I with no anti-aircraft artillery. When war broke out and Germany occupied Belgium and North-east France, it was realised that key installations in England could be attacked by air. As a result, a search for suitable anti-aircraft guns began. The Navy provided the initial 3-inch (76 mm) guns from its warships, approximately 18 by December 1914, for the defence of key installations in Britain, manned by RNVR crews, until the new specialised anti-aircraft version began production and entered service.[16] It was from then onwards operated by Royal Garrison Artillery crews, with drivers and crew for motor lorries provided by the Army Service Corps. However, the Mobile Anti-Aircraft Brigade based at Kenwood Barracks in London, continued to be manned by the RNVR, although under the operational control of the Army.[17]

Other earlier anti-aircraft guns based on the existing 13-pounder and 18-pounder guns proved inadequate, apart from the QF 13-pounder 9 cwt but even that could not reach high altitudes and fired a fairly light shell. The 3-inch 20 cwt with its powerful and stable in flight,[18] 16 lb (7.3 kg) shell and fairly high altitude was well suited to defending the United Kingdom against high-altitude Zeppelins and bombers. The 16-pound shell took 9.2 seconds to reach 5,000 ft (1,500 m) at 25 degrees from horizontal, 13.7 seconds to reach 10,000 ft (3,000 m) at 40 degrees, 18.8 seconds to reach 15,000 ft (4,600 m) at 55 degrees.[9] This means that the gun team had to calculate where the target would be 9 to 18 seconds ahead, determine the deflection and set the correct fuze length, load, aim and fire accordingly. Deflection was calculated mechanically and graphically using an optical height & rangefinder to provide data for the two piece Wilson-Dalby 'predictor', with the fuze length read off a scale mounted on the gun.

British time fuzes, required for airburst shooting, were powder burning (igniferous). However, the powder burning rate changed as air pressure reduced, making them erratic for the new vertical shooting. Modified fuzes reduced the variability but did not cure the problem. Britain lagged behind Germany in developing clockwork time fuzes. In addition, experience showed that the percussion mechanism in time fuzes, which burst the shrapnel shell on impact if the timer failed, had to be removed because AA shells could land among friendly troops and nearby civilians.[19] Igniferous fuzes had to have a gaine in order to detonate HE shells.

The carriage's short recoil of 11 inches (280 mm) allowed a higher rate of fire than for AA guns based on long-recoil field guns such as the QF 13-pounder 9 cwt.[20]

By June 1916, 202 3-inch 20 cwt were deployed in the air defence of Britain, of a total of 371 AA guns.[4]

The first guns arrived on the Western Front in November 1916 and by the end of 1916 it equipped 10 sections out of a total of 91.[21] An AA section consisted of two guns and became the standard organizational unit.

By the end of World War I, 257 (out of a total of 402 AA guns) were in land service in England on static and lorry mountings, and 102 (out of a total of 348) were in service on the Western Front[22] mounted on heavy lorries, typically the Peerless 4 Ton. In addition, many were mounted on Royal Navy ships.

- Demonstration of towing on 2-wheeled travelling platform

- Demonstration of deployment for action on cruciform travelling platform with wheels removed

- Mk I gun on Mk IV mounting on Peerless 4 ton lorry, WWI

- On HMAS Australia, December 1918

Performance

| Gun | muzzle velocity | Shell weight | Time to 5,000 feet (1,500 m) at 25° (seconds) |

Time to 10,000 feet (3,000 m) at 40° (seconds) |

Time to 15,000 feet (4,600 m) at 55° (seconds) |

Max. height[24] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QF 13 pdr 9 cwt | 1,990 feet per second (610 m/s) | 12.5 pounds (5.7 kg) | 10.1 | 15.5 | 22.1 | 19,000 feet (5,800 m) |

| QF 12 pdr 12 cwt | 2,200 feet per second (670 m/s) | 12.5 pounds (5.7 kg) | 9.1 | 14.1 | 19.1 | 20,000 feet (6,100 m) |

| QF 3-inch 20 cwt 1914 | 2,500 feet per second (760 m/s) | 12.5 pounds (5.7 kg) | 8.3 | 12.6 | 16.3 | 23,500 feet (7,200 m) |

| QF 3-inch 20 cwt 1916 | 2,000 feet per second (610 m/s) | 16 pounds (7.3 kg) | 9.2 | 13.7 | 18.8 | 22,000 feet (6,700 m)[25] |

| QF 4-inch Mk V naval gun | 2,350 feet per second (720 m/s) | 31 pounds (14 kg) | 4.4?? | 9.6 | 12.3 | 28,750 feet (8,760 m) |

World War II

At the beginning of World War II in 1939, Britain possessed approximately 500 of these guns. Over the 1930s, they had been gradually modernized, and a limited production line was set up at the Commonwealth Ordnance Factory Maribyrnong, Australia.[26] Initially most were in the heavy anti-aircraft (HAA) role until replaced by the new QF 3.7-inch (94 mm) gun. Some were deployed as light anti-aircraft guns (LAA) for airfield defence, being transferred to the RAF Regiment when this was formed in 1942, until more 40 mm Bofors guns arrived[27] However, it was discovered at mobilization that the 233 guns in HAA reserve were missing various parts and predicted fire instruments.[28] One hundred and twenty were in France with the British Expeditionary Force in November 1939, compared with 48 of the modern QF 3.7-inch AA gun.[29]

In 1941, 100 of the obsolete guns were converted to become the 3-inch 16 cwt anti-tank gun, firing a 12.5-pound (5.7 kg) armour-piercing shell.[30] They appear to have been mainly deployed in home defence. Some were mounted to Churchill tanks to become the "Gun Carrier, 3-inch, Mk I, Churchill (A22D)".

Naval gun

In World War II the gun was carried by S-class, U-class and V-class submarines.

It was also fitted to older destroyers, A-class to I class during refits in 1940, replacing a set of torpedo tubes, to increase their AA capabilities. Some smaller warships used this gun as well. In 1939 it was estimated the RN had 553 Mk I, 184 Mk II, 27 Mk III and 111 Mk IV guns in service.[2]

- A modernized 3-incher of 6th HAA Bde towed by an AEC truck, 1934

- An Australian gun of the same type with a Vickers predictor in Narrabeen, 1937

- A static mount of the 99th Anti-Aircraft Regiment in Kent, May 1940

- Churchill gun carrier in Dorset, March 1943

- On a U-class submarine, April 1943

Finnish use

Britain supplied 24 Mk 3 guns and 7 M/34 mechanical fire control computers to Finland during the Winter War of 30 November 1939 to March 1940 but they arrived too late to be used. They were used during the Continuation War of 1941–1944.[31]

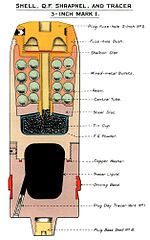

World War I ammunition

World War II ammunition

- Royal Navy gunner with fixed round in World War II

See also

Weapons of comparable role, performance and era

- Japanese type 88 75 mm AA gun

- United States 3-inch gun M1918

Surviving examples

- At the Royal Artillery Museum, London

- A gun at Pendennis Castle, Cornwall, UK, now displayed at Dover Castle, Kent, UK

- A gun captured by Israel from Egypt in the 1956 war, missing breech screw, is displayed at the Clandestine Immigration and Naval Museum, Haifa, Israel.

- A gun from the Egyptian ship "El Amir Faruk", sunk in 1948, missing the elevation mechanism, is displayed at the Clandestine Immigration and Naval Museum, Haifa, Israel.

- Mk 3 gun is displayed at the Ilmatorjuntamuseo, Tuusula, Finland.

- Mk III at Oulu garrison, Intiö district of Oulu, Finland

- A restored gun at Dover Castle, Kent, UK. During the summer months, weekly demonstration firings take place.[32]

References

- ^ a b c Hogg & Thurston 1972, page 78

- ^ a b Campbell, Naval Weapons of WWII, p.61-62.

- ^ a b c d e Hogg & Thurston 1972, page 79

- ^ a b Farndale 1988, page 397

- ^ Routledge 1994, page 9, 13

- ^ "77-77 MM CALIBRE CARTRIDGES". www.quarryhs.co.uk. Archived from the original on 17 January 2015. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ a b Routledge 1994, page 12

- ^ a b c d e Routledge 1994, page 13

- ^ a b Routledge 1994, page 9

- ^ Navweaps.com

- ^ Notes on Anti-Aircraft Guns. April 1917, page 22

- ^ Routledge 1994, page 43

- ^ Postan, Michael Moïssey; Hay, Denys; Scott, John Dick (1964). Design and Development of Weapons. Studies in Government and Industrial Organisation. H.M. Stationery Office. p. 284. ISBN 978-0-11-630089-8.

- ^ Routledge 1994, page 50

- ^ Routledge 1994, page 50-51

- ^ Routledge 1994, page 4-5

- ^ Rawlinson, Alfred, Sir, The defence of London, 1915–1918, 1923 (p.57)

- ^ Routledge 1994, page 24

- ^ Hogg & Thurston 1972, page 220

- ^ Hogg & Thurston 1972, page 68

- ^ Farndale 1986, page 364

- ^ Routledge 1994, page 27. Farndale 1988, page 342 quotes 56 in service in France (meaning Western Front) at the Armistice.

- ^ Routledge 1994, Page 9

- ^ Hogg & Thurston 1972, Page 234-235

- ^ Routledge 1994, Page 13

- ^ "RAAHC - Artillery Register - Manly, NSW, QF 3 inch 20 CWT Anti Aircraft Gun, Serial Number 4282".

- ^ Routledge 1994, page 50.

- ^ Routledge 1994, page 371

- ^ Routledge 1994, page 125

- ^ Nigel F Evans,British Artillery In World War 2. Anti-Tank Artillery

- ^ Jaeger Platoon: Finnish Army 1918 – 1945 Antiaircraft Guns Part 3: Heavy Guns

- ^ "Fortress Dover | English Heritage". www.english-heritage.org.uk. Retrieved 11 January 2017.

Bibliography

- Farndale, Sir Martin (1986). Western Front 1914–18. History of the Royal Regiment of Artillery. London: Royal Artillery Institution. ISBN 1-870114-00-0..

- Farndale, General Sir Martin (1988). Forgotten Fronts and the Home Base 1914–18. History of the Royal Regiment of Artillery. London: The Royal Artillery Institution. ISBN 1-870114-05-1.

- Hogg, I. V.; Thurston, L.F. (1972). British Artillery Weapons & Ammunition 1914–1918. London: Ian Allan. ISBN 978-0-7110-0381-1.

- Routledge, Brigadier NW (1994). Anti-Aircraft Artillery, 1914–55. History of the Royal Regiment of Artillery. London: Brassey's. ISBN 1-85753-099-3.

- Notes on Anti-Aircraft Guns, US Army War College, April 1917 – via Combined Arms Research Library

- Campbell, John (1985). Naval Weapons of World War Two. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-459-2.