Portuguese in Belgium

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 80,000[1] (Portuguese-Belgians and Portuguese residents in Belgium) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| Portuguese, French, Dutch | |

| Religion | |

| Roman Catholicism, Judaism, Irreligion | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Portuguese people, Portuguese Jews in the Netherlands, Portuguese Jews in the UK, Portuguese Jews in Turkey, Portuguese Jews in Israel, Portuguese in France, Portuguese in Germany, Portuguese in Luxembourg, Portuguese in the Netherlands |

Portuguese in Belgium (also known as Portuguese-Belgians / Belgian-Portuguese Community or, in Portuguese, as Portugueses na Bélgica / Comunidade portuguesa na Bélgica / Luso-belgas) are the citizens or residents of Belgium whose ethnic origins lie in Portugal.

Portuguese Belgians are Portuguese-born citizens with a Belgian citizenship or Belgian-born citizens of Portuguese ancestry or citizenship.

History

15th Century

Until the 19th century, Belgium, as we know it today, did not exist as an independent nation. The territory that is now Belgium was part of various larger political entities, including the Spanish Netherlands, the Austrian Netherlands, and the United Kingdom of the Netherlands. Nevertheless, there have always been interactions between Portugal and the region that would later become Belgium, mostly through trade or diplomatic relations.[2]

As commercial relations intensified in the 15th century, the Duke of Burgundy granted privileges to the Portuguese in Flanders on December 26, 1411. These privileges pertained to the weighing of goods, loading and unloading at various ports, carrying arms, and ensuring secure transactions with money changers.[3][4][5][6][7]

On January 10, 1430, Isabel of Portugal, daughter of D. João I and Philippa of Lancaster, the only sister in the renowned "illustrious generation," married Philip III, Duke of Burgundy, and Count of Flanders, whose territories already extended to Antwerp. With her came an additional 2,000 Portuguese, who engaged in significant activities in commerce, finance, and the arts. Isabel (1397–1471), amidst the wealthiest and most refined European court of the time, became a patron of the arts, represented her husband in several diplomatic missions, and exerted influence over her son, Charles the Bold, who succeeded him.[8][9][10][11][12][13]

With the support of the Portuguese, Philip initiated a shipyard for ship construction in Bruges. The privileges of the Portuguese were expanded on November 2, 1438, by a letter from the Duke in Brussels. This granted Portuguese merchants the ability to elect consuls with legal powers, as they knew and judged disputes arising among the Portuguese, with the right to appeal to the local judges. They were also granted the power to impose fines on those who did not comply, thereby acquiring complete civil jurisdiction over the Portuguese community, which governed itself by its own statutes.[14][15][16][17][18][19]

In 1445, the Portuguese feitoria (factory) was established in Bruges.[20][21]

16th Century

By the late 15th century, the decline of Bruges' port and the rise of Antwerp as the economic center of the Low Countries resulted in Portuguese merchants relocating to Antwerp.[22][23][24][25][26]

In 1499, the Portuguese trading post moved to Antwerp, and the community gained special privileges.

In the early 16th century, Antwerp emerged as a prominent shipping hub, frequented by Portuguese vessels laden with valuable spices such as pepper and cinnamon from Asia. The bustling port played a pivotal role in the lucrative spice trade. This unprecedented economic success positioned Antwerp as a vital player in the global trade landscape.[27][28] During the 16th century, Antwerp's Portuguese trading post played a significant role as a commercial hub, exchanging goods from the Atlantic Islands, Africa, the Orient, and Portugal for metals, artillery, and fabrics from Europe.[29]

In 1510, the Portuguese community obtained the status of "most-favored nation", gaining privileges, especially regarding the jurisdiction of two annually elected consuls, with one sometimes serving as the royal factor. These privileges were acknowledged and renewed in subsequent years.

In 1523, Damião de Góis became the secretary of the Portuguese Trading Post in Antwerp due to his Flemish ancestry, appointed by King John III.

Additionally, "Marranos" – Portuguese Jews fleeing persecution – contributed to the growing Portuguese population in Antwerp from 1526 onwards. The Jewish community in Antwerp flourished, and it played an essential role in the city's economic and cultural life. Their active involvement in trade, finance, and other commercial ventures contributed to Antwerp's continued prosperity and international standing.[30][31][32][33][34]

While historical records may not provide precise figures on the exact number of Portuguese Jews in Antwerp during this period, their presence was undoubtedly significant in shaping the city's character and growth. Today, Antwerp's Jewish community remains an integral part of its rich cultural heritage. In addition, around 5,000 Portuguese remain in Antwerp.[35][36][37]

Despite the initial success, over the years, the trading post accumulated a significant debt, leading John III of Portugal to close its operations. By Royal charter on February 15, 1549, he ordered the return of the factor João Rebelo and other officials to Portugal.[38]

During the reign of D. Sebastião, Jorge Pinto became consul of the Portuguese nation's house, assuming some of the trading post's functions.

Around 1576, about a fifth of the Portuguese population in Antwerp moved to Cologne due to changes in the Low Countries during the Dutch War of Independence. After the city's conquest by the Spanish troops, many Portuguese- especially the Jews – left for the Netherlands or for Hamburg.[39] Many had already emigrated towards the Ottoman Empire.[38]

17th to 19th Century

The foundation of the Dutch East India Company and conflicts between Portuguese and Dutch in the East led to the decline of the Portuguese trading post in Antwerp as well as to the emigration of many Portuguese. However, the trading post continued to play a crucial role until its eventual disappearance in 1795.[38]

20th Century

It was not until the 20th century that a more substantial Portuguese presence began to emerge in Belgium. After World War II, Belgium experienced economic growth and faced a labor shortage. To meet the demand for workers, the Belgian government signed bilateral agreements with several countries, including Portugal, to recruit foreign workers. As a result, many Portuguese migrants started arriving in Belgium in the 1960s and onwards.

During the early 1960s, in fact, Belgium experienced significant economic growth, which resulted in an increasing demand for labor across various sectors such as metallurgy, chemistry, construction, and transportation. This surge in labor requirements led to a relaxation of the legislation that previously mandated a work permit as a prerequisite for obtaining a residence permit for immigrants.[40]

As economic diversification progressed, the distribution of immigrant workers underwent changes. While industrial towns were once the primary destination for immigrants, this trend shifted. The arrival of Spanish, Portuguese, and Greek immigrants gave rise to distinct neighborhoods within cities, while Moroccans and Turks predominantly settled in major urban centers like Brussels, Antwerp, and Ghent.

The role of immigration went through a transformation during this period. Authorities and employers sought to restore demographic balance in response to the significant aging of the Belgian population. They hoped that family reunification would stabilize the immigrant workforce, which was considered quite transient. Consequently, a policy of encouraging the immigration of foreign families was implemented.[41]

One notable example of immigration during this era was the influx of Portuguese workers, who faced unique political and social realities in their home country. Portugal was characterized by a general stagnation in its agrarian, social, and political systems, coupled with the impact of brutal colonial wars in Angola and Mozambique, starting in 1961. Many Portuguese immigrants left their homeland not only for economic reasons but also due to political motives, although they refrained from seeking asylum. In addition, until the 60s there was a vibrant Portuguese community in the then Belgian Colony of the Belgian Congo. Upon independence in 1960, many Portuguese moved to Portuguese Angola, Portugal, Belgium or France.[42]

In 1978 an "Agreement between the Portuguese Government and the Belgian Government Regarding the Living and Working Conditions, Vocational Training, and Social and Cultural Promotion of Portuguese Workers and Their Family Members Residing in Belgium" was signed between the two countries.[43]

Belgium hasn't historically been amongst the traditional destinations chosen by Portuguese migrants, especially because of lack of linguistic affinity between the two countries, especially when dealing with the richer region of the Flandres. Nevertheless, starting in the late 1970s, in conjunction with the slowdown in departures towards France and the United States of America, Portuguese people have started opting for less "traditional" destinations such as Switzerland, Luxembourg and, although in lesser numbers, Belgium.

In the late 1980s and early 2000s, Belgium witnessed a new phase of immigration. There was a significant surge in migration from the Maghreb region and Central and Eastern Europe following the collapse of the communist bloc. On the other hand, immigration from Southern European countries such as Portugal decreased during this period.[44][45]

21st Century

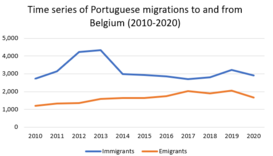

The number of Portuguese moving to Belgium soared in the first years of the 21st century, in particular after the 2008 Global recession and the consequent crisis that hit Portuguese economy.[46][47]

Of the approximately 53,200 Portuguese that arrived in Belgium since 2000, 76.85% did so after 2008 and 54.46% after 2012, year in which the unemployment rate in Portugal soared to 16.1%.[48]

The number of Portuguese nationals – thus excluding those who hold Belgian nationality as well – has doubled in the period 2000–2022, rising from approximately 26,000 people to almost 52,000 individuals.[49]

Since 2006, the annual influx of individuals born in Portugal entering Belgium has consistently exceeded 2,000 individuals with 11,700 Portuguese entering the nation between 2011 and 2013 in pursuit of enhanced economic prospects. Since 2013 emigration towards Belgium has slowed although, with Brexit and the consequent exclusion of the United Kingdom as a prime destination for Portuguese emigrants, Belgium might attract new prospective migrants.[50]

The Portuguese community in Belgium is fairly young, with only 10.3% of the Portuguese born population being over 65.

Portuguese migrants in Belgium generally tend to settle for shorter periods of a few years, as opposed to permanent migrations prevalent during the 1960s great emigration movements from Portugal towards France.[51][52]

In fact, since 2010 around 18,100 Portuguese have left Belgium. The emigration of Portuguese citizens has been constantly increasing since the first available year of the time series (2010). It is worth noting that, starting from 2014, the Portuguese unemployment rate has steadily fallen and the economic outlook has bettered. The sole exception occurred in 2020, during which a decline in the influx of Portuguese individuals was observed. This decline is most likely attributable to the Coronavirus pandemic.[53][54] Similarly, the influx of Portuguese migrants has steadily decreased since 2013, with the exception of 2019.

Despite being, theoretically, equal to other citizens as EU regulation states, many Portuguese in Belgium have faced discrimination in recent years. In particular, many Portuguese have been exploited and more are thought to be living a tough life. In some instances, such as in the construction sector, Belgian workers can earn more than three times the amount that a Portuguese worker receives for performing the same task. Many Portuguese have also been reported earning as little as €2 per hour.[55][56][57][58]

Dealing with the ancient Portuguese-Jewish community in Belgium, descendants of those who stayed after WWII and didn't take part in the aliyah – numbers today around 300 Portuguese-Jewish families. They are members of the Portuguese Synagogue in Antwerp.[59][60]

As of today, the Portuguese are part of a wider Portuguese-speaking community in Belgium, comprising around 11,000 people from PALOP countries (the overwhelming majority being from Angola or from Cape Verde), Timor-Leste or Macau[61][62][63][64] and 65,000 Brazilians.[65] People from CPLP countries thus number around 156,000 people, thus accounting for 1.33% of the population of Belgium.[66] The community of people from coming from CPLP countries in Belgium is in line with other Benelux countries: In Luxembourg there are around 174,000 people (26.4% of the population) while in The Netherlands there are around 147,500 people (0.84% of the population). In particular, Belgium hosts the second largest Portuguese diaspora of the region after Luxembourg.[67]

Demographics

According to Portuguese registers, in 2021 almost 80,000 Portuguese citizens are registered as living in Belgium.[54]

Similarly, as of 2022, almost 68,000 Belgians are of Portuguese descent, meaning people born in Portugal or children of at least one Portuguese-born parent.[61] The number of people of Portuguese background is lower than that of Portuguese nationals because many Portuguese may have been born in third countries such as France, Luxembourg, the Netherlands or Germany, countries neighbourhing Belgium and all having large Portuguese populations.

The Portuguese did not acquire in significant amount Belgian citizenship due to their status as EU citizens. In fact, even though according to Belgian legislation multiple citizenship is allowed, as Portuguese are EU citizens many find it unnecessary to acquire an additional citizenship that wouldn't give them any additional rights dealing with work or residence permits.

Interestingly, since the year 2000, only 4,951 Portuguese nationals have been naturalized as Belgian citizens, which accounts for a mere 0.6% of the total number of naturalizations. However, it is worth noting that the Portuguese represent 2.4% of the foreign population, meaning they are under-represented in the naturalization process.[54]

The Portuguese community in Belgium retains strong ties with its homeland and, between 2000 and 2021, it has sent approximately 1.105 billion euros (€) to Portugal in remittances. In the same timeframe, Belgians in Portugal (numbering around 6,100 individuals)[68] have sent approximately 39.42 million euros (€) to Belgium.[69]

Notable people

- Nelson Azevedo-Janelas (1998): Belgian footballer

- Thomas Azevedo (1991): Belgian footballer

- Rose Bertram (1994): Belgian model

- Veronique Branquinho (1973): a Belgian fashion designer

- Yannick Carrasco (1993): Belgian footballer

- Mayron De Almeida (1995): Belgian footballer

- Maria-Anna Galitzine (1954): Belgian traditionalist Catholic activist and member of the House of Habsburg-Lorraine

- Leopold III of Belgium (1901–1983): King of the Belgians from 23 February 1934 until his abdication on 16 July 1951

- Lio (1962): Portuguese-Belgian singer and Actor who was a pop icon in France and Belgium during the 1980s.

- Mário Matos (1988): Portuguese-Belgian footballer

- Diego Moreira (2004): Portuguese-Belgian footballer

- Helena Noguerra (1969): Belgian Actor

- Nuno Resende (1973): Portuguese singer

- Jonathan Sacoor (1999): Belgian sprinter

- Queen Elisabeth (1876–1965): Queen of the Belgians from 23 December 1909 to 17 February 1934 as the wife of King Albert I

See also

- Casa da Índia

- History of the Jews in Affaltrach

- History of the Jews in Hamburg

- Portuguese Empire

- Portuguese in France

- Portuguese in Germany

- Portuguese in Luxembourg

- Portuguese in the Netherlands

- Portuguese Jewish community in Hamburg

- Portuguese Renaissance

- Portuguese synagogue in Amsterdam

- Portuguese Luxembourger

Further reading

- FREIRE, Anselmo Braamcamp. Maria Brandoa, a do Crisfal. Lisboa: Archivo Historico Portuguez, 1908. Vol 6, cap. II, p. 322–442.

- Diogo Ramada Curto, Francisco Bethencourt, "O tempo de Vasco da Gama", DIFEL, 1998, ISBN 9728325479

- Fernand Braudel, Siân Reynolds,"Civilization and Capitalism, 15th–18th Century: The perspective of the world", University of California Press, 1992, ISBN 0520081161

- Bailey Wallys Diffie, Boyd C. Shafer, George Davison Winius, "Foundations of the Portuguese empire, 1415–1580", U of Minnesota Press, 1977, ISBN 0816607826

References

- ^ "Comunidade Portuguesa".

- ^ Matringe, Nadia; Heudre, Antoine (2017). "Le dépôt en foire au début de l'époque modern: Transfert de crédit et financement du commerce". Annales. Histoire, Sciences Sociales. 72 (2): 381–423. doi:10.1017/S0395264917000580. ISSN 0395-2649. JSTOR 90024565. S2CID 165924057.

- ^ "D. Dinis. 1261–1325, rei de Portugal – Arquivo Municipal Alfredo Pimenta – Archeevo". archeevo.amap.pt (in Portuguese). Retrieved 2023-07-22.

- ^ "XTF: Search Results added". pb.lib.berkeley.edu. Retrieved 2023-07-22.

- ^ "Correio Mor" (PDF).

- ^ "D. Dinis – Convento de Cristo". www.conventocristo.gov.pt. Retrieved 2023-07-22.

- ^ "A experiência na Flandres e a integração portuguesa na monarquia hispânica" (PDF).

- ^ "Biografias – Isabel de Portugal, Duquesa da Borgonha". monarquiaportuguesa.blogs.sapo.pt. Retrieved 2023-07-22.

- ^ Parisoto, Felipe. "D. Isabel de Portugal, Ínclita Duquesa da Borgonha (1430–1471), Diplomata Europeia do Século XV. Contributo para uma bibliografia crítica".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "De infanta de Portugal a duquesa de Borgonha" (PDF).

- ^ "Isabelle duchesse de Bourgogne".

- ^ Sommé, Monique (1995). "Les Portugais dans l'entourage de la duchesse de Bourgogne Isabelle de Portugal (1430–1471)". Revue du Nord. 77 (310): 321–343. doi:10.3406/rnord.1995.5006.

- ^ "Philip III | Duke of Burgundy, French Ruler & Patron of the Arts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 2023-06-11. Retrieved 2023-07-22.

- ^ Hughes, Muriel J. (1978-06-01). "The library of Philip the Bold and Margaret of Flanders, first Valois duke and duchess of Burgundy". Journal of Medieval History. 4 (2): 145–188. doi:10.1016/0304-4181(78)90004-0. ISSN 0304-4181.

- ^ Miranda, Flávio (2010-04-20). "Commerce, conflits et justice : les marchands portugais en Flandre à la fin du Moyen Âge". Annales de Bretagne et des Pays de l'Ouest. Anjou. Maine. Poitou-Charente. Touraine (in French) (117–1): 193–208. doi:10.4000/abpo.1018. ISSN 0399-0826. S2CID 161191259.

- ^ "Histoire Urbaine".

- ^ "Unesco". unesdoc.unesco.org. Retrieved 2023-07-22.

- ^ Van Houtte, J.-A. (1952). "Bruges et Anvers, marchés " nationaux " ou " internationaux ", du XIVe au XVIe siècle". Revue du Nord. 34 (134): 89–108. doi:10.3406/rnord.1952.2046.

- ^ "ISABELLE DE PORTUGAL ET BRUGES : DES RELATIONS PRIVILÉGIÉES".

- ^ "Feitoria de Bruges".

- ^ "Feitoria de Bruges". cctic.ese.ipsantarem.pt. Retrieved 2023-07-22.

- ^ Miranda, Flávio (2010-04-20). "Commerce, conflits et justice : les marchands portugais en Flandre à la fin du Moyen Âge". Annales de Bretagne et des Pays de l'Ouest. Anjou. Maine. Poitou-Charente. Touraine (in French) (117–1): 193–208. doi:10.4000/abpo.1018. ISSN 0399-0826. S2CID 161191259.

- ^ RAU, Virginia. "Feitores e feitorias - "Instrumentos" do comércio internacional português no Séc. XVI", Brotéria, Vol. 81, nº 5, 1965

- ^ Braudel, Fernand. "Civilization and Capitalism, 15th–18th Century: The perspective of the world", University of California Press, 1992, ISBN 0520081161

- ^ BOXER, Charles Ralph (1969). The Portuguese Seaborne Empire 1415–1825. Hutchinson. ISBN 0091310717

- ^ TRACY, James D., "The political economy of merchant empires", Cambridge University Press, 1997, ISBN 0521574641

- ^ "Feitoria Portuguesa".

- ^ "Antwerp in the Early 1500s". www.nga.gov. Retrieved 2023-07-22.

- ^ "Portugueses em Antuérpia".

- ^ "Feitoria Portuguesa de Antuérpia · DHLAB". projetos.dhlab.fcsh.unl.pt. Retrieved 2023-07-22.

- ^ "LES PORTUGAIS À ANVERS AU XVIiéme SIÈCLE. de LOPES. (Joaquim Mauricio): Good Soft Cover | Livraria Castro e Silva". www.iberlibro.com (in Spanish). Retrieved 2023-07-22.

- ^ "Les Portugais devant le Grand Conseil des Pays-Bas (1460–1580) | Os Portuguese Perante o Grande Conselho dos Países Baixos (1460–1580)". Artbooks4u. Retrieved 2023-07-22.

- ^ ""Les nouveaux chrétienes portugais à Anvers aux XVIe et XVIIe siècles" | Sefardiweb". www.proyectos.cchs.csic.es. Retrieved 2023-07-22.

- ^ Couto, Dejanirah. "Juifs et nouveaux-chrétiens portugais entre Anvers, l'Empire ottoman et l'Inde".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Público (2016-07-16). "As boas memórias da feitoria portuguesa em Antuérpia". Life&Style (in Portuguese). Retrieved 2023-07-22.

- ^ Révah, Israël Salvator (1963). "Pour l'histoire des Marranes à Anvers : recensements de la «Nation Portugaise » de 1571 à 1666". Revue des études juives. 122 (1): 123–147. doi:10.3406/rjuiv.1963.1439. S2CID 263181777.

- ^ "Étude sur les colonies marchandes méridionales (portugais, espagnols, italiens) à Anvers de 1488 à 1567 : contributions à l'histoire des débuts du capitalisme moderne | WorldCat.org". www.worldcat.org. Retrieved 2023-07-22.

- ^ a b c "Feitoria Portuguesa de Antuérpia – Arquivo Nacional da Torre do Tombo – DigitArq". digitarq.arquivos.pt. Retrieved 2023-07-22.

- ^ "Portugueses" (PDF).

- ^ "Une brève histoire de l'immigration en Belgique" (PDF).

- ^ "L'immigration en Belgique" (PDF).

- ^ "La communauté portugaise du Congo belge".

- ^ "Decreto n.º 22/79 Acordo entre o Governo Português e o Governo Belga Relativo às Condições de Vida e de Trabalho, à Formação Profissional e à Promoção Social e Cultural dos Trabalhadores Portugueses e dos Seus Familiares Residentes na Bélgica" (PDF).

- ^ "Historique de l'immigration en Belgique: Synthèse" (PDF).

- ^ "Etrangers qui viennent en Belgique | Belgium.be". www.belgium.be. Retrieved 2023-07-22.

- ^ Henriques, Ana Maria (2016-04-20). "Bélgica atrai cada vez mais portugueses: qual é o "segredo"?". PÚBLICO (in Portuguese). Retrieved 2023-07-22.

- ^ "Les Portugais de Belgique, le cœur à la Seleçao". Le Soir (in French). 2021-06-25. Retrieved 2023-07-22.

- ^ "Taxa de desemprego: total e por sexo (%)". www.pordata.pt. Retrieved 2023-07-14.

- ^ "Migration and migrant population statistics". ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 2023-07-22.

- ^ "Observatório da Emigração". observatorioemigracao.pt (in Portuguese). Retrieved 2023-07-14.

- ^ "Emigrantes: total e por tipo e sexo". www.pordata.pt. Retrieved 2023-07-14.

- ^ "Migrations | Statbel". statbel.fgov.be. Retrieved 2023-07-22.

- ^ "Emigration from Belgium". ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 2023-07-22.

- ^ a b c "Observatório da Emigração". observatorioemigracao.pt (in Portuguese). Retrieved 2023-07-22.

- ^ "Portugueses na Bélgica pagos a 2 euros à hora". www.cmjornal.pt (in European Portuguese). Retrieved 2023-07-22.

- ^ Belga (2023-07-22). "Des ouvriers portugais payés 3,4 euros l'heure sur un chantier gare du Nord". DHnet (in French). Retrieved 2023-07-22.

- ^ "Sindicato da Construção denuncia exploração de trabalhadores portugueses na Bélgica". SIC Notícias (in Portuguese). 2018-04-27. Retrieved 2023-07-22.

- ^ "Pedida investigação às condições de trabalho dos emigrantes na Bélgica". www.dn.pt (in European Portuguese). 2018-04-27. Retrieved 2023-07-22.

- ^ "Anvers – patrimoine juif, histoire juive, synagogues, musées, quartiers et sites juifs". JGuide Europe (in French). Retrieved 2023-07-22.

- ^ "JewishCom.be » Blog Archive » La Communauté Israélite de rite portugais d'Anvers" (in French). Retrieved 2023-07-22.

- ^ a b "Migratieachtergrond per gemeente". www.npdata.be. Retrieved 2023-07-22.

- ^ "Population by country of Birth". ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 2023-07-22.

- ^ "Population by citizenship". ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 2023-07-22.

- ^ "Acquisition of citizenship". ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 2023-07-22.

- ^ "Brasileiros no exterior" (PDF).

- ^ "Structure of the Population | Statbel". statbel.fgov.be. Retrieved 2023-07-22.

- ^ "Observatório da Emigração". observatorioemigracao.pt. Retrieved 2023-07-23.

- ^ "Sefstat" (PDF).

- ^ "Observatório da Emigração". observatorioemigracao.pt (in Portuguese). Retrieved 2023-07-28.