Portolan chart

Portolan charts are nautical charts, first made in the 13th century in the Mediterranean basin and later expanded to include other regions. The word portolan comes from the Italian portolano, meaning "related to ports or harbors", and which since at least the 17th century designates "a collection of sailing directions".[1]

Definition

The term "portolan chart" was coined in the 1890s because at the time it was assumed that these maps were related to portolani, medieval or early modern books of sailing directions.[2] Other names that have been proposed include rhumb line charts, compass charts or loxodromic charts[3] whereas modern French scholars prefer to call them nautical charts to avoid any relationship with portolani.[4]

Several definitions of portolan chart coexist in the literature. A narrow definition includes only medieval[5] or, at the latest, early modern sea charts (i.e. maps that primarily cover maritime rather than inland regions) that include a network of rhumb lines and do not show any indication of the use of latitude or longitude coordinates.[6] The geographic scope of these mostly medieval portolan charts is limited to the Mediterranean and Black Seas with possible extensions to West European coasts up to Scandinavia and West African coasts down to Guinea. Some authors further restrict the term portolan chart to single-sheet maps drawn on parchment,[7] whereas books that contain several sea charts are called nautical atlases.

A broader definition of portolan chart accepts any sea chart or atlas that meets the following series of stylistic requirements: drawn by hand, with a network of rhumb lines that emanate from the center of hidden circles, focused on the coasts and islands, with place names written perpendicular to the coastline on the land side and with sparse information about the interior of landmasses.[8][9] This broader definition encompasses charts of potentially any sea and even maps of the entire world, which are sometimes called nautical planispheres, provided they meet the aforesaid criteria. It includes nautical charts that depict latitude scales and have been called "latitude charts" by other authors to distinguish them from proper portolan charts, which are believed to have been constructed on the basis of dead reckoning information.[6]

Contents

Rhumb lines

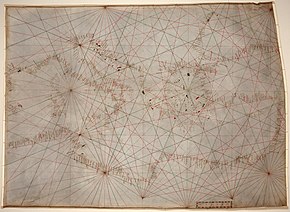

Portolan charts are characterized by their rhumbline networks, which emanate out from compass roses located at various points on the map. The lines in these networks are generated by compass observations to show lines of constant bearing. Though often called rhumbs, they are better called "windrose lines": As cartographic historian Leo Bagrow states, "…the word [loxodromic or rhumb chart] is wrongly applied to the sea-charts of this period, since a loxodrome gives an accurate course only when the chart is drawn on a suitable projection. Cartometric investigation has revealed that no projection was used in the early charts…".[10]

The straight lines shown criss-crossing portolan charts represent the sixteen directions (or headings) of the mariner's compass from a given point, which became thirty-two directions from around 1450.[11] The principal lines are oriented to the magnetic north pole.[12] Thus the grid lines varied slightly for charts produced in different eras, due to the natural changes of the Earth's magnetic declination.[12] These lines are similar to the compass rose displayed on later maps and charts. "All portolan charts have wind roses, though not necessarily complete with the full thirty-two points; the compass rose ... seems to have been a Catalan innovation".[13]

Use

The portolan chart combined the exact notations of the text of the periplus or pilot book with the decorative illustrations of a medieval T and O map. In addition, the charts provided realistic depictions of shores. They were meant for practical use by mariners of the period. Portolans failed to take into account the curvature of the Earth; as a result, they were not helpful as navigational tools for crossing the open ocean, and were replaced by later Mercator projection charts.[12] Portolans were most useful in close quarters' identification of landmarks.[12] Portolani were also useful for navigation in smaller bodies of water, such as the Mediterranean, Black, or Red Seas.

Production

Most extant portolan charts from before 1500 are drawn on vellum, which is a high-quality type of parchment, made from calf skin. Single charts were normally rolled whereas those that formed part of atlases were pasted on wood or cardboard supports.[14]

The earliest surviving explanations of how to draw a portolan chart date from the 16th century,[15] so the techniques used by medieval mapmakers can only be inferred. The instruments available in the Middle Ages are believed to have been a ruler, a pair of dividers, a pen, and inks of various colors. Drawing probably started with the windrose lines and then the mapmaker copied the coastal outlines from some earlier chart. Place names, geographic details and decoration were added in the end.[16]

Production centers

Two main families of portolan charts were distinguished by origin, according to 19th-century historians: Italian, developed mainly in Genoa, Venice and Rome; and Spanish, with Palma de Mallorca as a main center of production. Portuguese charts were believed to be derived from the Spanish. Arab portolan charts were not recognized until the second half of the 20th century.

Italian

The copious number of Italian portolan charts begins in the mid 13th century, with the oldest called Carta Pisana, which is kept in the National Library in Paris. To the next century belong the Carignano Chart, disappeared from the National Archive of Florence where it had been conserved for a long time; cartographic works of the Genoese Pietro Vesconte, the illustrator of the work of Marino Sanudo; the chart of Francisco Pizigano (1373), with stylistic influence from Mallorca; and those of Beccario, Canepa and the brothers Benincasa, natives of Ancona. The fifteenth-century Luxoro Atlas, whose authorship is anonymous, is held at the Biblioteca Civica Berio in Genoa.

Catalan

The Spanish introduced a novelty in nautical cartography, with geographical maps having common stylistic representation of certain accidents and locations. The masterpiece of the Majorcan portolan charts is the Catalan Atlas made by Abraham Cresques in 1375, and kept in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France in Paris.

Abraham Cresques was a Majorcan Jew who worked at the service of Pedro IV of Aragon. In his "buxolarum" [=magnetic compass] workshop he was helped by his son Jafuda. The Atlas is a World Map, that is, world map and regions of the Earth with the various peoples who live there. The work was done at the request of Prince John, son of Pedro IV, desirous of a faithful representation of the world from west to east. 12 sheets form the world map on tables, linked to each other by scroll and screen layout. Each table measures 69 by 49 cm. The first four texts are filled with geographical and astronomical tables and calendars. The newest of the Cresques World Map is the representation of Asia, from the Caspian sea to Cathay (China), which takes into account information from Marco Polo, and Jordanus .

In the 14th century, also highlights the work of Guillem Soler, which cultivates both styles, the purely nautical and nautical-geographical. To the 15th century corresponds the famous portolan chart by Gabriel Vallseca, (1439), kept in the Maritime Museum of Barcelona, notable for its delicacy of execution and lively picturesque details, masked by a spot of ink left by Frédéric Chopin and George Sand.[17]

Portuguese

The Portuguese portolan charts come from the Majorcan tradition,[18] and as traditional portolan charts did not fulfill the requirements demanded by the expansion of the geographic horizons attained by Portuguese and Spaniards, they superposed the astronomical lines of the equator and tropics on top of the wind line network, and they continued being elaborated over the 16th and 17th centuries.

Arab

Three medieval portolan charts written in Arabic are preserved:[19]

- Map of Ahmed ibn Suleiman al-Tangi from 1413 to 1414.[20]

- Map of Ibrahim al-Tabib al-Mursi from 1461

- Map of western Europe, anonymous and undated, preserved in the Ambrosiana Library, dating from the 14th [21] or 15th centuries.

In addition there is a detailed description of a nautical Arab map of the Mediterranean in the Encyclopedia of the Egyptian Ibn Fadl Allah al-'Umari, written between 1330 and 1348.[19] There are also descriptions limited to smaller geographic regions, in a work of Ibn Sa'id al Maghribi (13th century) and even in the work of Al-Idrisi (12th century).[21]

Theories of origin

The origins of portolan charts are obscure, having no known predecessors.[22] One study[23] concludes that portolans originated from earlier charts drawn on what is now called the Mercator projection, stating that portolans are mosaics of smaller charts, each with their own scale and orientation, and suggesting that the cartographic capabilities of whichever civilization produced the antecedent charts was more advanced than is currently acknowledged.[24] These ideas are rejected by established researchers in the field, however, who find ample evidence of medieval origins and construction methods.[25][26]

It has been proposed that portolan charts evolved from the mental maps that Mediterranean pilots had used since ancient times, which had been transmitted orally over generations.[27]

Evolution

The earliest portolan charts focused on the Mediterranean and Black Sea coasts, with only partial and sometimes sketchy depiction of Atlantic coasts up to Scandinavia. In the 15th and 16th centuries, with the beginning of the Age of Discovery, the scope of portolan charts expanded south down to the Gulf of Guinea. Charts also started to be drawn by Portuguese and Spanish mapmakers for the newly explored seas in Africa, America, South Asia and the Pacific.

See also

- Antillia

- Catalan chart

- Classical compass winds

- Cornaro Atlas

- La Cartografía Mallorquina

- Majorcan cartographic school

- Rule of Marteloio

- Thames school of chartmakers

References

- ^ Campbell, Tony. "'Portolan charts from the late thirteenth century to 1500' (Additions, Corrections, Updates)". Map History / History of Cartography: THE Gateway to the Subject. Retrieved 8 December 2018.

- ^ Campbell 1987, page 375

- ^ Roel, Nicolai (2016). The enigma of the origin of Portolan charts : a geodetic analysis of the hypothesis of a medieval origin. Leiden. pp. 11–12. ISBN 9789004282971. OCLC 932069190.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Vagnon, Emmanuelle (2013). "La représentation cartographique de l'espace maritime". In Gautier Dalché, Patrick (ed.). La Terre connaissance, représentations, mesure au Moyen Âge (in French). Brepols. ISBN 978-2-503-54753-4.

- ^ For example, Ramon Pujades only considers charts earlier than 1470 in his census.Pujades i Bataller, Ramon Josep (2007). Les cartes portolanes: la representació medieval d'una mar solcada. Institut Cartogràfic de Catalunya, l’Institut d’Estudis Catalans i l’Institut Europeu de la Mediterrània. ISBN 978-84-393-7576-0.

- ^ a b Gaspar, Joaquim Alves (June 2013). "From the Portolan Chart to the Latitude Chart: The silent cartographic revolution" (PDF). CFC (216): 67–77.

- ^ Delano-Smith, Catherine (7–8 June 2018). Emergent Maps: Questioning the Rise and Function of the Portolan Chart and the Regional Map in the Middle Ages. Second International Workshop on the Origin and Evolution of Portolan Charts. Lisbon.

- ^ Pflederer, Richard (2009). Census of Portolan Charts and Atlases. Privately printed.

- ^ Campbell, Tony (18 November 2016). "Cartographic innovations by the early portolan chartmakers". Map History / History of Cartography: THE Gateway to the Subject. Retrieved 8 December 2018.

- ^ Leo Bagrow (2010). History of Cartography. Transaction Publishers. p. 65. ISBN 978-1-4128-2518-4.

- ^ Campbell 1987, page 396

- ^ a b c d Rehmeyer, Julie. The Mapmaker's Mystery, Discover, June 2014, pp. 44–49 (subscription).

- ^ Campbell 1987, page 395

- ^ Campbell 1987, page 376

- ^ For example Martín Cortés, Arte de navegar, 1551

- ^ Campbell 1987, pages 391-392

- ^ George Sand (1843). Oeuvres complètes de George Sand. Perrotin. pp. 69–.

- ^ Estudos de História, Volume III. UC Biblioteca Geral 1. pp. 10–. GGKEY:7186FCQBHS5.

- ^ a b Ducène, Jean-Charles (2013-06-01). "Le portulan arabe décrit par Al-'Umari" (PDF). CFC (216): 81–90.

- ^ Herrera Casais, Mónica. 'The 1413-14 sea chart of Ahmad al-Ţanjī', in: Emilia Calvo, Mercè Comes, Roser Puig & Mónica Rius (eds) A shared legacy: Islamic science East and West. Homage to Prof. J.M. Millàs Vallicrosa (Barcelona: Universitat de Barcelona, 2008) pp.283-307.

- ^ a b Vernet Ginés, John (1962). "The Maghreb in the Biblioteca Ambrosiana Chart". 16: 1–16.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Campbell 1987, page 380

- ^ Nicolai, R. (2014) A critical review of the hypothesis of a medieval origin for portolan charts Archived 2022-06-14 at the Wayback Machine. Uitgeverij Educatieve Media

- ^ Jacobs, Frank. "Portolan Charts 'Too Accurate' to be Medieval". Big Think. Retrieved 30 August 2018.

- ^ Gaspar, Joaquim Alves (2015). "Review of Roel Nicolai's article by Joaquim Alves Gaspar". Maps in History. 53.

- ^ Campbell, Tony (2015). "Review of Roel Nicolai's article by Tony Campbell". Maps in History. 53.

- ^ Campbell, Tony (2021). "Mediterranean portolan charts: their origin in the mental maps of medieval sailors, their function and their early development". Retrieved 6 October 2021.

Further reading

- Konrad Kretschmer, Die italienischen Portolane des Mittelalters, Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte der Kartographie und Nautik, Berlin, Veröffentlichungen des Instituts für Meereskunde und des geographischen Instituts an der Universität Berlin, Vol. 13, 1909. (available online)

- Alessandra D. Debanne, Lo Compasso de navegare. Edizione del codice Hamilton 396 con commento linguistico e glossario, Brussels, Peter Lang for the Gruppo degli italianisti delle Università francofone del Belgio, 2011.

- Patrick Gautier Dalché, Carte marine et portulan au XIIe siècle. Le Liber de existencia rivieriarum et forma maris nostri Mediterranei, Pise, circa 1200, Roma, École Française de Rome, 1995. (available online)

- Tony Campbell, "Portolan Charts from the Late Thirteenth Century to 1500", Chapter 19 of The History of Cartography, Volume I. U. of Chicago Press, 74th edition (May 15, 1987). (available online)

External links

- A Critical Re-examination of Portolan Charts, with a Reassessment of Their Replication and Seaboard Function, ongoing collection of essays and tabulated data by Tony Campbell, comprising about 30 separate web publications, over 120 tables and graphs, a census of surviving charts pre-1500 and a comprehensive bibliography.

- J. Rey Pastor & E. Garcia Camarero La cartografía mallorquina (in Spanish)

- Images of portolan charts:

- Portolan Charts mini-site, University of Minnesota

- Portolan Charts, samples from Yale University