Great auk

| Great auk Temporal range: | |

|---|---|

| |

| Specimen No. 8 and replica egg in the Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum, Glasgow | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Charadriiformes |

| Family: | Alcidae |

| Genus: | †Pinguinus Bonnaterre, 1791 |

| Species: | †P. impennis |

| Binomial name | |

| †Pinguinus impennis | |

| |

| Approximate range (in blue) with known breeding sites indicated by yellow marks[4][5] | |

| Synonyms | |

The great auk (Pinguinus impennis), also known as the penguin or garefowl, is a species of flightless alcid that became extinct in the mid-19th century. It was the only modern species in the genus Pinguinus. It is unrelated to the penguins of the Southern Hemisphere, which were named for their resemblance to this species.

It bred on rocky, remote islands with easy access to the ocean and a plentiful food supply, a rarity in nature that provided only a few breeding sites for the great auks. During the non-breeding season, the auk foraged in the waters of the North Atlantic, ranging as far south as northern Spain and along the coastlines of Canada, Greenland, Iceland, the Faroe Islands, Norway, Ireland, and Great Britain.

The bird was 75 to 85 centimetres (30 to 33 inches) tall and weighed about 5 kilograms (11 pounds), making it the largest alcid to survive into the modern era, and the second-largest member of the alcid family overall (the prehistoric Miomancalla was larger).[6] It had a black back and a white belly. The black beak was heavy and hooked, with grooves on its surface. During summer, great auk plumage showed a white patch over each eye. During winter, the great auk lost these patches, instead developing a white band stretching between the eyes. The wings were only 15 cm (6 in) long, rendering the bird flightless. Instead, the great auk was a powerful swimmer, a trait that it used in hunting. Its favourite prey were fish, including Atlantic menhaden and capelin, and crustaceans. Although agile in the water, it was clumsy on land. Great auk pairs mated for life. They nested in extremely dense and social colonies, laying one egg on bare rock. The egg was white with variable brown marbling. Both parents participated in the incubation of the egg for around six weeks before the young hatched. The young left the nest site after two to three weeks, although the parents continued to care for it.

The great auk was an important part of many Native American cultures, both as a food source and as a symbolic item. Many Maritime Archaic people were buried with great auk bones. One burial discovered included someone covered by more than 200 great auk beaks, which are presumed to be the remnants of a cloak made of great auks' skins. Early European explorers to the Americas used the great auk as a convenient food source or as fishing bait, reducing its numbers. The bird's down was in high demand in Europe, a factor that largely eliminated the European populations by the mid-16th century. Around the same time, nations such as Great Britain began to realize that the great auk was disappearing and it became the beneficiary of many early environmental laws, but despite that, the great auk were still hunted.

Its growing rarity increased interest from European museums and private collectors in obtaining the skins and eggs of the bird. On 3 June 1844, the last two confirmed specimens were killed on Eldey, off the coast of Iceland, ending the last known breeding attempt. Later reports of roaming individuals being seen or caught are unconfirmed. A report of one great auk in 1852 is considered by some to be the last sighting of a member of the species. The great auk is mentioned in several novels, and the scientific journal of the American Ornithological Society was named The Auk (now Ornithology) in honor of the bird until 2021.

Taxonomy and evolution

Analysis of mtDNA sequences has confirmed morphological and biogeographical studies suggesting that the razorbill is the closest living relative of the great auk.[7] The great auk also was related closely to the little auk or dovekie, which underwent a radically different evolution compared to Pinguinus. Due to its outward similarity to the razorbill (apart from flightlessness and size), the great auk often was placed in the genus Alca, following Linnaeus.

The fossil record (especially the sister species, Pinguinus alfrednewtoni) and molecular evidence show that the three closely related genera diverged soon after their common ancestor, a bird probably similar to a stout Xantus's murrelet, had spread to the coasts of the Atlantic. Apparently, by that time, the murres, or Atlantic guillemots, already had split from the other Atlantic alcids. Razorbill-like birds were common in the Atlantic during the Pliocene, but the evolution of the little auk is sparsely documented.[7] The molecular data are compatible with either possibility, but the weight of evidence suggests placing the great auk in a distinct genus.[7] Some ornithologists still believe it is more appropriate to retain the species in the genus Alca.[9] It is the only recorded British bird made extinct in historic times.[10]

The following cladogram shows the placement of the great auk among its closest relatives, based on a 2004 genetic study:[11]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Pinguinus alfrednewtoni was a larger, and also flightless, member of the genus Pinguinus that lived during the Early Pliocene.[12] Known from bones found in the Yorktown Formation of the Lee Creek Mine in North Carolina, it is believed to have split, along with the great auk, from a common ancestor. Pinguinus alfrednewtoni lived in the western Atlantic, while the great auk lived in the eastern Atlantic. After the former died out following the Pliocene, the great auk took over its territory.[12] The great auk was not related closely to the other extinct genera of flightless alcids, Mancalla, Praemancalla, and Alcodes.[13]

Etymology

The great auk was one of the 4,400 animal species formally described by Carl Linnaeus in his eighteenth-century work Systema Naturae, in which it was given the binomial Alca impennis.[15] The name Alca is a Latin derivative of the Scandinavian word for razorbills and their relatives.[16] The bird was known in literature even before this and was described by Charles d'Ecluse in 1605 as Mergus Americanus. This also included a woodcut which represents the oldest unambiguous visual depictions of the bird.[17]

The species was not placed in its own scientific genus, Pinguinus, until 1791.[18] The generic name is derived from the Spanish, Portuguese, and French name for the species, in turn from Latin pinguis meaning "plump", and the specific name, impennis, is from Latin and refers to the lack of flight feathers, or pennae.[16]

The Irish name for the great auk is falcóg mhór, meaning "big seabird/auk". The Basque name is arponaz, meaning "spearbill". Its early French name was apponatz, while modern French uses grand pingouin. The Norse called the great auk geirfugl, which means "spearbird". This has led to an alternative English common name for the bird, garefowl or gairfowl.[19]: 333 The Inuit name for the great auk was isarukitsok, which meant "little wing".[19]: 314

The word "penguin" first appears in the sixteenth century as a synonym for "great auk".[20] Although the etymology is debated, the generic name "penguin" may be derived from the Welsh pen gwyn "white head", either because the birds lived in New Brunswick on White Head Island (Pen Gwyn in Welsh) or because the great auk had such large white circles on its head. When European explorers discovered what today are known as penguins in the Southern Hemisphere, they noticed their similar appearance to the great auk and named them after this bird, although biologically, they are not closely related.[21]: 10 Whalers also lumped the northern and southern birds together under the common name "woggins".[22]

Description

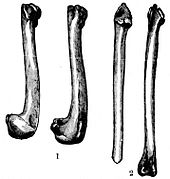

Standing about 75 to 85 centimetres (30 to 33 in) tall and weighing approximately 5 kilograms (11 lb) as adult birds,[23] the flightless great auk was the second-largest member of both its family and the order Charadriiformes overall, surpassed only by the mancalline Miomancalla. It is, however, the largest species to survive into modern times. The great auks that lived farther north averaged larger than the more southerly members of the species.[13] Males and females were similar in plumage, although there is evidence for differences in size, particularly in the bill and femur length.[24][25][21]: 8 The back was primarily a glossy black, and the belly was white. The neck and legs were short, and the head and wings were small. During summer, it developed a wide white eye patch over each eye, which had a hazel or chestnut iris.[21]: 9, 15, 28 [19]: 310 Auks are known for their close resemblance to penguins, their webbed feet and countershading are a result of convergent evolution in the water.[26] During winter the great auk moulted and lost this eye patch, which was replaced with a wide white band and a gray line of feathers that stretched from the eye to the ear.[21]: 8 During the summer, its chin and throat were blackish-brown and the inside of the mouth was yellow.[24] In winter, the throat became white.[21]: 8 Some individuals reportedly had grey plumage on their flanks, but the purpose, seasonal duration, and frequency of this variation is unknown.[27] The bill was large at 11 cm (4+1⁄2 in) long and curved downward at the top;[21]: 28 the bill also had deep white grooves in both the upper and lower mandibles, up to seven on the upper mandible and twelve on the lower mandible in summer, although there were fewer in winter.[28][21]: 29 The wings were only 15 cm (6 in) in length and the longest wing feathers were only 10 cm (4 in) long.[21]: 28 Its feet and short claws were black, while the webbed skin between the toes was brownish black.[28] The legs were far back on the bird's body, which gave it powerful swimming and diving abilities.[19]: 312

Hatchlings were described as grey and downy, but their exact appearance is unknown since no skins exist today.[28] Juvenile birds had fewer prominent grooves in their beaks than adults and they had mottled white and black necks,[29] while the eye spot found in adults was not present; instead, a grey line ran through the eyes (which still had white eye rings) to just below the ears.[24]

Great Auk calls included low croaking and a hoarse scream. A captive great auk was observed making a gurgling noise when anxious. It is not known what its other vocalizations were, but it is believed that they were similar to those of the razorbill, only louder and deeper.[30]

Distribution and habitat

The great auk was found in the cold North Atlantic coastal waters along the coasts of Canada, the northeastern United States, Norway, Greenland, Iceland, the Faroe Islands, Ireland, Great Britain, France, and the Iberian Peninsula.[31][21]: 5 Pleistocene fossils indicate the great auk also inhabited Southern France, Italy, and other coasts of the Mediterranean basin.[32][19]: 314 It was common on the Grand Banks of Newfoundland.[33] In recorded history, the great auk typically did not go farther south than Massachusetts Bay in the winter.[34] Great auk bones have been found as far south as Florida, where it may have been present during four periods: approximately 1000 BC and 1000 AD, as well as during the fifteenth century and the seventeenth century.[35][36] It has been suggested that some of the bones discovered in Florida may be the result of aboriginal trading.[34] In the eastern Atlantic, the southernmost records of this species are two isolated bones, one from Madeira[37] and another from the Neolithic site of El Harhoura 2 in Morocco.[38]

The great auk left the North Atlantic waters for land only to breed, even roosting at sea when not breeding.[39][21]: 29 The rookeries of the great auk were found from Baffin Bay to the Gulf of St. Lawrence, across the far northern Atlantic, including Iceland, and in Norway and the British Isles in Europe.[21]: 29–30 [40] For their nesting colonies the great auks required rocky islands with sloping shorelines that provided access to the sea. These were very limiting requirements and it is believed that the great auk never had more than 20 breeding colonies.[19]: 312 The nesting sites also needed to be close to rich feeding areas and to be far enough from the mainland to discourage visitation by predators such as humans and polar bears.[33] The localities of only seven former breeding colonies are known: Papa Westray in the Orkney Islands, St. Kilda off Scotland, Grimsey Island, Eldey Island, Geirfuglasker near Iceland, Funk Island near Newfoundland,[41] and the Bird Rocks (Rochers-aux-Oiseaux) in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Records suggest that this species may have bred on Cape Cod in Massachusetts.[19]: 312 By the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, the breeding range of the great auk was restricted to Funk Island, Grimsey Island, Eldey Island, the Gulf of St. Lawrence, and the St. Kilda islands.[21]: 30 Funk Island was the largest known breeding colony.[42] After the chicks fledged, the great auk migrated north and south away from the breeding colonies and they tended to go southward during late autumn and winter.[34]

Ecology and behaviour

The great auk was never observed and described by modern scientists during its existence and is only known from the accounts of laymen, such as sailors, so its behaviour is not well known and difficult to reconstruct. Much may be inferred from its close, living relative, the razorbill, as well as from remaining soft tissue.[9]

Great auks walked slowly and sometimes used their wings to help them traverse rough terrain.[29] When they did run, it was awkwardly and with short steps in a straight line.[39] They had few natural predators, mainly large marine mammals, such as the orca, and white-tailed eagles.[39] Polar bears preyed on nesting colonies of the great auk.[21]: 35 Based on observations by the Naturalist Otto Fabricius (the only scientist to make primary observations on the great auk), some auks were "stupid and tame" whilst others were difficult to approach which he suggested was related to the bird's age.[40] Humans preyed upon them as food, for feathers, and as specimens for museums and private collections.[2] Great auks reacted to noises but were rarely frightened by the sight of something.[19]: 315 They used their bills aggressively both in the dense nesting sites and when threatened or captured by humans.[39] These birds are believed to have had a life span of approximately 20 to 25 years.[19]: 313 During the winter, the great auk migrated south, either in pairs or in small groups, but never with the entire nesting colony.[21]: 32

The great auk was generally an excellent swimmer, using its wings to propel itself underwater.[29] While swimming, the head was held up but the neck was drawn in.[39] This species was capable of banking, veering, and turning underwater.[21]: 32 The great auk was known to dive to depths of 75 m (250 ft) and it has been claimed that the species was able to dive to depths of 1 km (3,300 ft; 550 fathoms).[19]: 311 To conserve energy, most dives were shallow.[43] It also could hold its breath for 15 minutes, longer than a seal. Its ability to dive so deeply reduced competition with other alcid species. The great auk was capable of accelerating underwater, and then shooting out of the water to land on a rocky ledge above the ocean's surface.[21]: 32

Diet

This alcid typically fed in shoaling waters that were shallower than those frequented by other alcids,[43] although after the breeding season, they had been sighted as far as 500 km (270 nmi) from land.[43] They are believed to have fed cooperatively in flocks.[43] Their main food was fish, usually 12 to 20 cm (4+1⁄2 to 8 in) in length and weighing 40 to 50 g (1+3⁄8 to 1+3⁄4 oz), but occasionally their prey was up to half the bird's length. Based on remains associated with great auk bones found on Funk Island and on ecological and morphological considerations, it seems that Atlantic menhaden and capelin were their favoured prey.[44] Other fish suggested as potential prey include lumpsuckers, shorthorn sculpins, cod, sand lance, as well as crustaceans.[19]: 311 [43] The young of the great auk are believed to have eaten plankton and, possibly, fish and crustaceans regurgitated by adults.[42][19]: 313

Reproduction

Historical descriptions of the great auk breeding behaviour are somewhat unreliable.[45] Great Auks began pairing in early and mid-May.[46] They are believed to have mated for life (although some theorize that great auks could have mated outside their pair, a trait seen in the razorbill).[39][19]: 313 Once paired, they nested at the base of cliffs in colonies, likely where they copulated.[21]: 28 [39] Mated pairs had a social display in which they bobbed their heads and displayed their white eye patch, bill markings, and yellow mouth.[39] These colonies were extremely crowded and dense, with some estimates stating that there was a nesting great auk for every 1 square metre (11 sq ft) of land.[39] These colonies were very social.[39] When the colonies included other species of alcid, the great auks were dominant due to their size.[39]

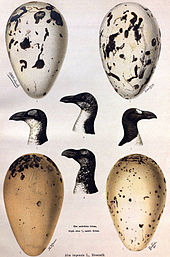

Female great auks would lay only one egg each year, between late May and early June, although they could lay a replacement egg if the first one was lost.[21]: 32 [46] In years when there was a shortage of food, the great auks did not breed.[47] A single egg was laid on bare ground up to 100 metres (330 ft) from shore.[29][21]: 33 The egg was ovate and elongate in shape, and it averaged 12.4 cm (4+7⁄8 in) in length and 7.6 cm (3 in) across at the widest point.[18][21]: 35 The egg was yellowish white to light ochre with a varying pattern of black, brown, or greyish spots and lines that often were congregated on the large end.[29][48] It is believed that the variation in the egg streaks enabled the parents to recognize their egg among those in the vast colony.[46] The pair took turns incubating the egg in an upright position for the 39 to 44 days before the egg hatched, typically in June, although eggs could be present at the colonies as late as August.[21]: 35 [46]

The parents also took turns feeding their chicks. According to one account, the chick was covered with grey down.[19]: 313 The young bird took only two or three weeks to mature enough to abandon the nest and land for the water, typically around the middle of July.[21]: 35 [46] The parents cared for their young after they fledged, and adults would be seen swimming with their young perched on their backs.[46] Great auks matured sexually when they were four to seven years old.[47]

Relationship with humans

The great auk was a food source for Neanderthals more than 100,000 years ago, as evidenced by well-cleaned bones found by their campfires. Images believed to depict the great auk also were carved into the walls of the El Pendo Cave in Camargo, Spain, and Paglicci, Italy, more than 35,000 years ago,[21]: 5–6 and cave paintings 20,000 years old have been found in France's Grotte Cosquer.[17][19]: 314

Native Americans valued the great auk as a food source during the winter and as an important cultural symbol. Images of the great auk have been found in bone necklaces.[21]: 36 A person buried at the Maritime Archaic site at Port au Choix, Newfoundland, dating to about 2000 BC, was found surrounded by more than 200 great auk beaks, which are believed to have been part of a suit made from their skins, with the heads left attached as decoration.[49] Nearly half of the bird bones found in graves at this site were of the great auk, suggesting that it had great cultural significance for the Maritime Archaic people.[50] The extinct Beothuks of Newfoundland made pudding out of the eggs of the great auk.[19]: 313 The Dorset Eskimos also hunted it. The Saqqaq in Greenland overhunted the species, causing a local reduction in range.[50]

Later, European sailors used the great auks as a navigational beacon, as the presence of these birds signaled that the Grand Banks of Newfoundland were near.[19]: 314

This species is estimated to have had a maximum population in the millions.[19]: 313 The great auk was hunted on a significant scale for food, eggs, and its down feathers from at least the eighth century. Prior to that, hunting by local natives may be documented from Late Stone Age Scandinavia and eastern North America,[51] as well as from early fifth century Labrador, where the bird seems to have occurred only as stragglers.[52] Early explorers, including Jacques Cartier, and numerous ships attempting to find gold on Baffin Island were not provisioned with food for the journey home, and therefore, used great auks as both a convenient food source and bait for fishing. Reportedly, some of the later vessels anchored next to a colony and ran out of planks to the land. The sailors then herded hundreds of great auks onto the ships, where they were slaughtered.[21]: 38–39 Some authors have questioned the reports of this hunting method and whether it was successful.[50] Great auk eggs were also a valued food source, as the eggs were three times the size of a murre's and had a large yolk.[50] These sailors also introduced rats onto the islands[48] which preyed upon nests.

Extinction

The Little Ice Age may have reduced the population of the great auk by exposing more of their breeding islands to predation by polar bears, but massive exploitation by humans for their down drastically reduced the population,[47] with recent evidence indicating the latter alone is likely the primary driver of its extinction.[b] By the mid-sixteenth century, the nesting colonies along the European side of the Atlantic were nearly all eliminated by humans killing this bird for its down, which was used to make pillows.[21]: 40 In 1553, the great auk received its first official protection. In 1794, Great Britain banned the killing of this species for its feathers.[19]: 330 In St. John's, those violating a 1775 law banning hunting the great auk for its feathers or eggs were publicly flogged, though hunting for use as fishing bait was still permitted.[50] On the North American side, eider down initially was preferred, but once the eiders were nearly driven to extinction in the 1770s, down collectors switched to the great auk at the same time that hunting for food, fishing bait, and oil decreased.[50][19]: 329

The great auk had disappeared from Funk Island by 1800. An account by Aaron Thomas of HMS Boston from 1794 described how the bird had been slaughtered systematically until then:

If you come for their Feathers you do not give yourself the trouble of killing them, but lay hold of one and pluck the best of the Feathers. You then turn the poor Penguin adrift, with his skin half naked and torn off, to perish at his leisure. This is not a very humane method but it is the common practice. While you abide on this island you are in the constant practice of horrid cruelties for you not only skin them Alive, but you burn them Alive also to cook their Bodies with. You take a kettle with you into which you put a Penguin or two, you kindle a fire under it, and this fire is made of the unfortunate Penguins themselves. Their bodies being oily soon produce a Flame; there is no wood on the island.[9]

With its increasing rarity, specimens of the great auk and its eggs became collectible and highly prized by rich Europeans, and the loss of a large number of its eggs to collection contributed to the demise of the species. Eggers, individuals who visited the nesting sites of the great auk to collect their eggs, quickly realized that the birds did not all lay their eggs on the same day, so they could make return visits to the same breeding colony. Eggers only collected the eggs without embryos and typically, discarded the eggs with embryos growing inside of them.[21]: 35

On the islet of Stac an Armin, St. Kilda, Scotland, in July 1840, the last great auk seen in Britain was caught and killed.[54] Three men from St. Kilda caught a single "garefowl", noticing its little wings and the large white spot on its head. They tied it up and kept it alive for three days until a large storm arose. Believing that the bird was a witch and was causing the storm, they then killed it by beating it with a stick.[9][55]

The last colony of great auks lived on Geirfuglasker (the "Great Auk Rock") off Iceland. This islet was a volcanic rock surrounded by cliffs that made it inaccessible to humans, but in 1830, the islet submerged after a volcanic eruption, and the birds moved to the nearby island of Eldey, which was accessible from a single side. When the colony initially was discovered in 1835, nearly fifty birds were present. Museums, desiring the skins of the great auk for preservation and display, quickly began collecting birds from the colony.[21]: 43 The last pair, found incubating an egg, was killed there on 3 June 1844, on request from a merchant who wanted specimens.[56][c]

Jón Brandsson and Sigurður Ísleifsson, the men who had killed the last birds, were interviewed by great auk specialist John Wolley,[59] and Sigurður described the act as follows:

The rocks were covered with blackbirds [guillemots] and there were the Geirfugles ... They walked slowly. Jón Brandsson crept up with his arms open. The bird that Jón got went into a corner but [mine] was going to the edge of the cliff. It walked like a man ... but moved its feet quickly. [I] caught it close to the edge – a precipice many fathoms deep. Its wings lay close to the sides – not hanging out. I took him by the neck and he flapped his wings. He made no cry. I strangled him.[8]: 82–83

A later claim of a live individual sighted in 1852 on the Grand Banks of Newfoundland has been accepted by the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources.[2]

There is an ongoing discussion about the possibilities for reviving the great auk using its DNA from specimens collected. This possibility is controversial.[60]

Preserved specimens

Today, 78 skins of the great auk remain, mostly in museum collections, along with approximately 75 eggs and 24 complete skeletons. All but four of the surviving skins are in summer plumage, and only two of these are immature. No hatchling specimens exist. Each egg and skin has been assigned a number by specialists.[9] Although thousands of isolated bones were collected from nineteenth century Funk Island to Neolithic middens, only a few complete skeletons exist.[61] Natural mummies also are known from Funk Island, and the eyes and internal organs of the last two birds from 1844 are stored in the Zoological Museum, Copenhagen. The whereabouts of the skins from the last two individuals have been unknown for more than a hundred years, but that mystery has been partly resolved using DNA extracted from the organs of the last individuals and the skins of the candidate specimens suggested by Errol Fuller[9] (those in Übersee-Museum Bremen, Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences, Zoological Museum of Kiel University, Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History, and Landesmuseum Natur und Mensch Oldenburg). A positive match was found between the organs from the male individual and the skin now in the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences in Brussels. No match was found between the female organs and a specimen from Fuller's list, but authors speculate that the skin in Cincinnati Museum of Natural History and Science may be a potential candidate due to a common history with the L.A. specimen.[62]

Following the bird's extinction, remains of the great auk increased dramatically in value, and auctions of specimens created intense interest in Victorian Britain, where 15 specimens are now located, the largest number of any country.[9] A specimen was bought in 1971 by the Icelandic Museum of National History for £9000, which placed it in the Guinness Book of Records as the most expensive stuffed bird ever sold.[63] The price of its eggs sometimes reached up to 11 times the amount earned by a skilled worker in a year.[19]: 331 The present whereabouts of six of the eggs are unknown. Several other eggs have been destroyed accidentally. Two mounted skins were destroyed in the twentieth century, one in the Mainz Museum during the Second World War, and one in the Museu Bocage, Lisbon that was destroyed by a fire in 1978.[9]

Cultural depictions

Children's books

Charles Kingsley's The Water-Babies: A Fairy Tale for a Land-Baby (1863) features the last great auk (referred to in the book as a gairfowl) telling the tale of the demise of her species.[64] Different illustrations of the auk are included in the original 1863 version, the 1889 version illustrated by Linley Sambourne,[65] 1916 by Frank A. Nankivell,[66] and 1916 by Jessie Willcox Smith.[67] Kinglsey's auk implicates the "nasty fellows" who "shot us so, and knocked us on the head, and took our eggs." While Kingsley portrays the extinction as sad, he provides his opinion that "there are better things come in her place," namely human colonization of the islands for the cod fishing industry, which would serve to feed the poor. He concludes the discussion with a quote from Tennyson: "The old order changeth, giving place to the new; And God fulfils Himself in many ways.”

Enid Blyton's The Island of Adventure (1944) sends one of the protagonists on a failed search for what he believes is a lost colony of the species.[68]

Literature and journalism

The great auk also is present in a wide variety of other works of fiction.

In the short story The Harbor-Master by Robert W. Chambers, the discovery and attempted recovery of the last known pair of great auks is central to the plot (which also involves a proto-Lovecraftian element of suspense). The story first appeared in Ainslee's Magazine (August 1898)[69] and was slightly revised to become the first five chapters of Chambers' episodic novel In Search of the Unknown, (Harper and Brothers Publishers, New York, 1904).

Penguin Island, a 1908 French satirical novel by the Nobel Prize winning author Anatole France, narrates the fictional history of a great auk population that is mistakenly baptized by a nearsighted missionary.[70]

In his novel Ulysses (1922), James Joyce mentions the bird while the novel's main character is drifting into sleep. He associates the great auk with the mythical roc as a method of formally returning the main character to a sleepy land of fantasy and memory.[71]

W. S. Merwin mentions the great auk in a short litany of extinct animals in his poem "For a Coming Extinction", one of the seminal poems from his 1967 collection, "The Lice".[72]

Night of the Auk, a 1956 Broadway drama by Arch Oboler, depicts a group of astronauts returning from the Moon to discover that a full-blown nuclear war has broken out. Obeler draws a parallel between the anthropogenic extinction of the great auk and of the story's nuclear extinction of humankind.[73]

A great auk is collected by fictional naturalist Stephen Maturin in the Patrick O'Brian historical novel The Surgeon's Mate (1980). This work also details the harvesting of a colony of auks.[74]

Farley Mowat devotes the first section, "Spearbill", of his book Sea of Slaughter (1984) to the history of the great auk.[75]

Elizabeth Kolbert's Pulitzer Prize-winning book, The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History (2014), includes a chapter on the great auk.[76]

- Monument on Reykjanes Peninsula, Iceland

- Monument on Fogo Island, Canada

- Monument to the last British great auk at Fowl Craig, Orkney

Performing arts

The great auk is the subject of a ballet, Still Life at the Penguin Café (1988),[77] and a song, "A Dream Too Far", in the ecological musical Rockford's Rock Opera (2010).[78]

Mascots

The great auk is the mascot of the Archmere Academy in Claymont, Delaware,[79] and the Adelaide University Choral Society (AUCS) in Australia.[80]

The great auk was formerly the mascot of the Lindsay Frost campus of Sir Sandford Fleming College in Ontario.[81] In 2012, the two separate sports programs of Fleming College were combined[82] and the great auk mascot went extinct. The Lindsay Frost campus student owned bar, student center, and lounge is still known as the Auk's Lodge.[83]

It was also the mascot of the now ended Knowledge Masters educational competition.[84][85]

Names

The scientific journal of the American Ornithologists' Union, Ornithology , was named The Auk until 2021 in honor of this bird.[19]

According to Homer Hickam's memoir, Rocket Boys, and its film production, October Sky, the early rockets he and his friends built, ironically were named "Auk".[86]

A cigarette company, the British Great Auk Cigarettes, was named after this bird.[19]

Fine arts

Walton Ford, the American painter, has featured great auks in two paintings: The Witch of St. Kilda and Funk Island.[87]

The English painter and writer Errol Fuller produced Last Stand for his monograph on the species.[9]

The great auk also appeared on one stamp in a set of five depicting extinct birds issued by Cuba in 1974.[88]

See also

Notes

- ^ Bewick stated "This species is not numerous anywhere: it inhabits Norway, Iceland, The Ferro Islands, Greenland, and other cold regions of the north, but is seldom seen on the British shores."[14]

- ^ Taken together, our data do not provide any evidence that great auks were at risk of extinction before the onset of intensive human hunting in the early 16th century. In addition, our population viability analyses reveal that even if the great auk had not been under threat by environmental change, human hunting alone could have been sufficient to cause its extinction. — J. E. Thomas, et al. (2019)[53]

- ^ A date of 3 July 1844 is given by various online sources,[57][58] but does not accord with the original publication and print sources.

References

- ^ Finlayson, Clive (2011). Avian survivors: The History and Biogeography of Palearctic Birds. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 157. ISBN 978-1408137314.

- ^ a b c BirdLife International (2021). "Pinguinus impennis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2021: e.T22694856A205919631. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-3.RLTS.T22694856A205919631.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ "NatureServe Explorer 2.0". explorer.natureserve.org. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ^ Grieve, Symington (1885). The Great Auk, or Garefowl: Its history, archaeology, and remains. Thomas C. Jack, London. ISBN 978-0665066245.

- ^ Parkin, Thomas (1894). The Great Auk, or Garefowl. J.E. Budd, Printer. Retrieved 14 May 2010.

- ^ Smith, N (2015). "Evolution of body mass in the Pan-Alcidae (Aves, Charadriiformes): the effects of combining neontological and paleontological data". Paleobiology. 42 (1): 8–26. Bibcode:2016Pbio...42....8S. doi:10.1017/pab.2015.24. S2CID 83934750.

- ^ a b c Moum, Truls; Arnason, Ulfur; Árnason, Einar (2002). "Mitochondrial DNA sequence evolution and phylogeny of the Atlantic Alcidae, including the extinct Great Auk (Pinguinus impennis)". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 19 (9). Oxford: Oxford University Press: 1434–1439. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a004206. PMID 12200471.

- ^ a b Fuller, Errol (1999). The Great Auk. Southborough, Kent, UK: Privately Published. ISBN 0-9533553-0-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Fuller, Errol (2003) [1999]. The Great Auk: The Extinction of the Original Penguin. Bunker Hill Publishing. p. 34. ISBN 978-1-59373-003-1. see also Fuller (1999).[8]

- ^ Bourne, W.R.P. (1993). "The story of the Great Auk Pinguinis impennis". Archives of Natural History. 20 (2): 257–278. doi:10.3366/anh.1993.20.2.257.

- ^ Thomas, G.H.; Wills, M.A.; Székely, T.S. (2004). "A supertree approach to shorebird phylogeny". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 4: 28. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-4-28. PMC 515296. PMID 15329156.

- ^ a b Olson, Storrs L.; Rasmussen, Pamela C. (2001). "Miocene and Pliocene Birds from the Lee Creek Mine, North Carolina". In Ray, Clayton E. (ed.). Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology. Vol. 90. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press. p. 279. Archived from the original on 27 February 2012. Retrieved 11 May 2010.

- ^ a b Montevecchi, William A.; Kirk, David A. (1996). "Systematics". Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology. The Birds of North America Online. Great Auk (Pinguinus impennis). Ithaca, NY: Cornell University. Retrieved 29 April 2010.

- ^ Bewick, Thomas (1847) [1804]. A History of British Birds. Vol. 2: Water Birds. Newcastle: R.E. Bewick. pp. 405–406.

- ^ Linnaeus, C. (1758). Systema naturae (in Latin). Vol. I. Stockholm: Lars Salvius. p. 130.

- ^ a b Johnsgard, Paul A. (1987). Diving Birds of North America. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. pp. 265–266. ISBN 0-8032-2566-0. Retrieved 11 May 2010.

- ^ a b Lozoya, Arturo Valledor De; García, David González; Parish, Jolyon (1 April 2016). "A great auk for the Sun King". Archives of Natural History. 43 (1): 41–56. doi:10.3366/anh.2016.0345.

- ^ a b Gaskell, Jeremy (2000). Who Killed the Great Auk?. Oxford University Press (US). p. 152. ISBN 0-19-856478-3.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w Cokinos, Christopher (2000). Hope is the Thing with Feathers: A personal chronicle of vanished birds. New York: Warner Books. ISBN 0-446-67749-3.

- ^ "Pingouin: Etymologie de Pingouin". Centre National de Ressources Textuelles et Lexicales. Retrieved 25 January 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab Crofford, Emily (1989). Gone Forever: The Great Auk. New York: Crestwood House. ISBN 0-89686-459-6.

- ^ Giaimo, Cara (26 October 2016). "What's A Woggin? A Bird, a Word, and a Linguistic Mystery". Atlas Obscura. Retrieved 2 December 2016.

Whalers wrote about woggins all the time. What in the world were they?

- ^ Livezey, Bradley C. (1988). "Morphometrics of flightlessness in the Alcidae" (PDF). The Auk. 105 (4). Berkeley: University of California Press: 681–698. doi:10.1093/auk/105.4.681. Retrieved 8 May 2009.

- ^ a b c Montevecchi, William A.; Kirk, David A. (1996). "Characteristics". Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology. The Birds of North America Online. Great Auk (Pinguinus impennis). Ithaca, NY: Cornell University. Retrieved 29 April 2010.

- ^ Montevecchi, William A.; Kirk, David A. (1996). "Measurements". Cornell Lab of Ornithology. The Birds of North America Online. Great Auk (Pinguinus impennis). Ithaca, NY: Cornell University. Retrieved 29 April 2010.

- ^ "The "aukward" truth about penguins and their flightless doppelgangers". 25 August 2021.

- ^ Rothschild, Walter (1907). Extinct Birds (PDF). London: Hutchinson & Co.

- ^ a b c Montevecchi, William A.; Kirk, David A. (1996). "Appearance". Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology. The Birds of North America Online. Great Auk (Pinguinus impennis). Ithaca, NY: Cornell University. Retrieved 29 April 2010.

- ^ a b c d e Morris, Reverend Francis O. (1864). A History of British Birds. Vol. 6. Groombridge and Sons, Paternoster Way, London. pp. 56–58.

- ^ Montevecchi, William A.; David A. Kirk (1996). "Sounds-Great Auk (Pinguinus impennis)". The Birds of North America Online. Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ^ Pimenta, Carlos M.; Figueiredo, Silvério; Moreno García, Marta (2008). "Novo registo de Pinguim (Pinguinus impennis) no Plistocénico de Portugal" (PDF). Revista portuguesa de arqueologia. 11 (2): 361–370. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 April 2017.

- ^ "Pinguinus impennis (great auk)". Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- ^ a b Montevecchi, William A.; David A. Kirk (1996). "Habitat-Great Auk (Pinguinus impennis)". The Birds of North America Online. Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Retrieved 29 April 2010. (subscription required)

- ^ a b c Montevecchi, William A.; David A. Kirk (1996). "Migration – Great Auk (Pinguinus impennis)". The Birds of North America Online. Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Retrieved 29 April 2010.

- ^ Weigel, Penelope Hermes (1958). "Great Auk Remains from a Florida Shell Midden" (PDF). Auk. 75 (2). Berkeley: University of California Press: 215–216. doi:10.2307/4081895. JSTOR 4081895. Retrieved 8 May 2009.

- ^ Brodkorb, Pierce (1960). "Great Auk and Common Murre from a Florida Midden" (PDF). Auk. 77 (3). Berkeley: University of California Press: 342–343. doi:10.2307/4082490. JSTOR 4082490. Retrieved 8 May 2009.

- ^ Pieper, H. (1985). The fossil land birds of Madeira and Porto Santo. Bocagiana. Museu de História Natural do Funchal, Nº88.

- ^ Campmas, E., Laroulandie, V., Michel, P., Amani, F., Nespoulet, R., & Mohammed, A. E. H. (2010). 22 "A great auk (Pinguinus impennis) in North Africa: discovery of". In Birds in Archaeology: Proceedings of the 6th Meeting of the ICAZ Bird Working Group in Groningen (23.8-27.8. 2008) (Vol. 12, p. 233). Barkhuis.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Montevecchi, William A.; David A. Kirk (1996). "Behavior-Great Auk (Pinguinus impennis)". The Birds of North America Online. Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Retrieved 28 April 2010. (subscription required)

- ^ a b Meldegaard, Morten (1988). "The Great Auk, Pinguinus impennis (L.) in Greenland" (PDF). Historical Biology. 1 (2): 145–178. Bibcode:1988HBio....1..145M. doi:10.1080/08912968809386472. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 December 2005. Retrieved 11 May 2010.

- ^ Milne, John. "Relics of the Great Auk on Funk Island", The Field, 27 March – 3 April 1875.

- ^ a b Montevecchi, William A.; David A. Kirk (1996). "Great Auk (Pinguinus impennis)". The Birds of North America Online. Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ^ a b c d e Montevecchi, William A.; David A. Kirk (1996). "Food Habits-Great Auk (Pinguinus impennis)". The Birds of North America Online. Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Retrieved 29 April 2010. (subscription required)

- ^ Olson, Storrs L; Swift, Camm C.; Mokhiber, Carmine (1979). "An attempt to determine the prey of the Great Auk (Pinguinus impennis)". The Auk. 96 (4): 790–792. JSTOR 4085666.

- ^ Gaskell, J. (2003). "Remarks on the terminology used to describe developmental behaviour among the auks (Alcidae), with particular reference to that of the Great Auk Pinguinus impennis". Ibis. 146 (2): 231–240. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919x.2003.00227.x.

- ^ a b c d e f Montevecchi, William A.; David A. Kirk (1996). "Breeding-Great Auk (Pinguinus impennis)". The Birds of North America Online. Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Retrieved 29 April 2010. (subscription required)

- ^ a b c Montevecchi, William A.; David A. Kirk (1996). "Demography-Great Auk (Pinguinus impennis)". The Birds of North America Online. Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Retrieved 29 April 2010.

- ^ a b "Great Auk egg". Norfolk Museums & Archaeology Service. Archived from the original on 9 February 2009. Retrieved 8 May 2009.

- ^ Tuck, James A. (1976). "Ancient peoples of Port au Choix: The excavation of an Archaic Indian cemetery in Newfoundland". Newfoundland Social and Economic Studies. 17. St. John's: Institute of Social and Economic Research, Memorial U of Newfoundland: 261.

- ^ a b c d e f Montevecchi, William A.; David A. Kirk (1996). "Conservation-Great Auk (Pinguinus impennis)". The Birds of North America Online. Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Retrieved 29 April 2010. (subscription required)

- ^ Greenway, James C. (1967). Extinct and Vanishing Birds of the World (2nd ed.). New York: Dover Publications. pp. 271–291. ISBN 978-0-486-21869-4.

- ^ Jordan, Richard H; Storrs L. Olson (1982). "First record of the Great Auk (Pinguinus impennis) from Labrador" (PDF). The Auk. 99 (1). University of California Press: 167–168. doi:10.2307/4086034. JSTOR 4086034. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 January 2014. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ^ Thomas, Jessica E.; et al. (26 November 2019). "Demographic reconstruction from ancient DNA supports rapid extinction of the great auk". eLife. 8. doi:10.7554/eLife.47509. PMC 6879203. PMID 31767056.

- ^ Rackwitz, Martin (2007). Travels to Terra Incognita: The Scottish Highlands and Hebrides in Early Modern Travellers' Accounts C. 1600 to 1800. Waxmann Verlag. p. 347. ISBN 978-3-8309-1699-4.

- ^ Gaskell, Jeremy (2000). Who Killed the Great Auk?. Oxford UP. p. 142. ISBN 978-0-19-856478-2.

- ^ Newton, Alfred (1861). "Abstract of Mr. J. Wolley's Researches in Iceland respecting the Gare-fowl or Great Auk (Alea impennis, Linn.)". Ibis. 3 (4): 374–399. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1861.tb08857.x.

- ^ "Jul 3, 1844 CE: Great Auks Become Extinct". National Geographic.

- ^ "The extinction of The Great Auk". National Audubon Society. 22 December 2015.

- ^ Newton, Alfred (1861). "Abstract of Mr. J. Wolley's Researches in Iceland respecting the Gare-fowl or Great Auk (Alea impennis, Linn.)". Ibis. 3 (4): 374–399. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1861.tb08857.x.

- ^ "Why Efforts to Bring Extinct Species Back from the Dead Miss the Point – Scientific American". Scientific American. 308 (6): 12. 2013. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0613-12. PMID 23729057.

- ^ Luther, Dieter (1996). Die ausgestorbenen Vögel der Welt. Die neue Brehm-Bücherei (in German). Vol. 424 (4th ed.). Heidelberg, DE: Westarp-Wissenschaften. pp. 78–84. ISBN 3-89432-213-6.

- ^ Thomas, Jessica E.; Carvalho, Gary R.; Haile, James; Martin, Michael D.; Castruita, Jose A. Samaniego; Niemann, Jonas; Sinding, Mikkel-Holger S.; Sandoval-Velasco, Marcela; Rawlence, Nicolas J. (15 June 2017). "An 'Aukward' Tale: A Genetic Approach to Discover the Whereabouts of the Last Great Auks". Genes. 8 (6): 164. doi:10.3390/genes8060164. PMC 5485528. PMID 28617333.

- ^ Guinness Book of Records 1972.

- ^ Kingsley, Charles (1863). The Water-Babies: A Fairy Tale for a Land-Baby. London & Cambridge: Macmillan and Co. pp. 251, 257–265.

- ^ "The Water-Babies, by Charles Kingsley". www.gutenberg.org. Retrieved 8 November 2024.

- ^ "The water-babies". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Retrieved 8 November 2024.

- ^ Smith, Jessie Willcox (1916). "And there he saw the last of the gairfowl". www.loc.gov. Retrieved 8 November 2024.

- ^ Blyton, Enid (1944). The Island of Adventure. London: Macmillan.

- ^ "Ainslee's magazine. V.3 (1899)". pp. 10 v. hdl:2027/umn.319510007402581.

- ^ France, Anatole. Penguin Island. Project Gutenberg. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ^ Joyce, James (2007). Ulysses. Charleston, SC: BiblioLife. p. 682. ISBN 978-1-4346-0387-6.

- ^ Merwin (15 March 2019). "For a Coming Extinction". Poetry Foundation. Retrieved 27 March 2019.

- ^ Oboler, Arch (1958). Night of the Auk. New York: Horizon Press. LCCN 58-13553.

- ^ O'Brian, Patrick (1981). The Surgeon's Mate. New York: W.W. Norton and Company. pp. 84–85. ISBN 0-393-30820-0.

- ^ Mowat, Farley (1986). Sea of Slaughter. New York: Bantam Books. p. 18. ISBN 0-553-34269-X.

- ^ "Excerpt: The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History | Audubon". www.audubon.org. 10 February 2014. Retrieved 7 November 2024.

- ^ Jeffes, Simon (2002). 'Still Life' at the Penguin Cafe. London: Peters Edition Ltd. ISBN 0-9542720-0-5.

- ^ "Durka-The Great Auk". Rockford's Rock Opera. 2010. Retrieved 10 May 2010.

- ^ "Archmere AUK Named Most Unique HS Mascot in DE, Moves on to Regionals!". Archmere Academy. 6 March 2013. Retrieved 21 May 2017.

- ^ Holzknecht, Karin (2005). "O'Sqweek 2005" (PDF). Adelaide University Choral Society. p. 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 July 2008. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ^ "Fleming College Auk's Lodge Student Association". Fleming College Auk's Lodge Student Association. 15 April 2010. Archived from the original on 11 July 2011. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ^ Fleming's Auks and Knights athletics merger Archived 27 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine 11 April 2012. Evolution in Sport.

- ^ "Auk's Lodge Student Centre". Frost Student Association. Fleming College. Retrieved 6 February 2023.

- ^ "Knowledge Master Open academic competition". greatauk.com. Archived from the original on 18 September 2013. Retrieved 3 July 2012.

- ^ Schettle, Liz (17 December 2004). "Competition summons inner intellect". The Oshkosh West Index. Archived from the original on 2 June 2011. Retrieved 29 April 2010.

- ^ Hickam, Homer (2006). "Books – Rocket Boys / October Sky". Homer Hickam Online. Archived from the original on 5 May 2010. Retrieved 29 April 2010.

- ^ Ford, Walton (2009). Pancha Tantra (illustrated ed.). Los Angeles: Taschen America LLC. ISBN 978-3-8228-5237-8.

- ^ Burns, Phillip (6 July 2003). "Dodo Stamps". Pib's Home on the Web. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

External links

- . Popular Science Monthly. Vol. 33. August 1888. ISSN 0161-7370 – via Wikisource.

- "Auk egg auction". Time. 26 November 1934.

- "Great Auk". Audubon fact sheet. audubon.org. Archived from the original on 14 June 2010.

- "The Great Auk". Natural Histories (audio documentary). BBC Radio.