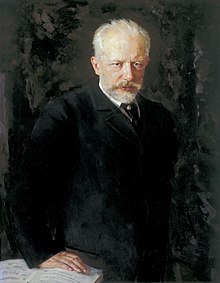

Piano Concerto No. 3 (Tchaikovsky)

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky's Piano Concerto No. 3 in E-flat major was at first conceived by him as a symphony in the same key. But he abandoned that idea, jetisoned all but the planned first movement, and reworked this in 1893 as a one-movement Allegro brillante for piano and orchestra. His last completed work, it was duly published as Opus 75 the next year, after he died, but given by publisher Jurgenson the title "Concerto No. 3 pour Piano avec accompagnement d'Orchestre".

Academic dispute

Despite the composer's stated intentions, there remains argument as to what form this composition might have taken had he continued work on it. Dispute revolves around two remaining movements from the planned symphony. Left in sketch form when Tchaikovsky died in 1893, these were made by his student and fellow composer Sergei Taneyev into a work for piano and orchestra titled Andante and Finale and published in 1897 as Tchaikovsky's "Opus 79". Whether it was worth Taneyev's efforts to do so after Tchaikovsky had expressed doubts about the movements' quality and whether the Andante and Finale should ever be performed alongside the Allegro brillante remain matters of argument. Most pianists play only Opus 75.

Completion as a symphony

In the 1950s Russian musicologist and composer Semyon Bogatyrev used Tchaikovsky's sketches, including those behind Opus 75 and "Opus 79", to conjecturally construct a Tchaikovsky "Symphony No. 7."

Setting as a ballet

Tchaikovsky's Piano Concerto No. 3 was in 1956 choreographed, fittingly under the title Allegro brillante, by George Balanchine for New York City Ballet.

Structure

Three musical subjects are presented in the single-movement Allegro brillante, as is also the case with the opening movements of Tchaikovsky's previous two piano concertos. The opening theme is lively, the second more lyrical and the third akin to a vigorous folk dance. While the development section begins with piano and orchestra collaborating, the musical forces quickly become segregated. The orchestra is given a lengthy section to itself, while the piano completes the development with a cadenza. The structure of the recapitulation is regular, followed by a vigorous coda.[1]

Opening theme

Instrumentation

The concerto is scored for piano solo; piccolo; two flutes; two oboes; two clarinets; two bassoons; four horns; two trumpets; three trombones; tuba; timpani and strings.

From symphony to concerto

History

Tchaikovsky's first mention of using the sketches of his abandoned Symphony in E-flat as the basis for a piano concerto came early in April 1893.[2] He began work on July 5, completing the first movement eight days later. Though he worked quickly, Tchaikovsky did not find the job a pleasant one—a note on the manuscript reads, "The end, God be thanked!" He did not score this movement until autumn.[3]

In June Tchaikovsky was in London to conduct a performance of his Fourth Symphony. There he ran into his friend, the French pianist Louis Diémer, whom he had met in Paris five years earlier during a festival of Tchaikovsky's chamber works. Diémer had performed Tchaikovsky's Concert Fantasia, in a two-piano arrangement with the composer at the second piano.[4] Diémer was one of the major French pianists of his time.[5] Sometime during their reacquaintance, Tchaikovsky might have mentioned the concerto upon which he had been working. Regardless, he decided to dedicate the work to Diémer.[6]

After finishing the Pathétique symphony, Tchaikovsky turned once again to the concerto, only to experience another wave of doubt. He confided to pianist Alexander Siloti, "As music it hasn’t come out badly—but it's pretty ungrateful."[7] He wrote to Polish pianist and composer Zygmunt Stojowski on October 6, 1893, "As I wrote to you, my new Symphony is finished. I am now working on the scoring of my new (third) concerto for our dear Diémer. When you see him, please tell him that when I proceeded to work on it, I realized that this concerto is of depressing and threatening length. Consequently I decided to leave only part one which in itself will constitute an entire concerto. The work will only improve the more since the last two parts were not worth very much."[8]

The choice of a single-movement Allegro de concert or Concertstück would have been in line with French piano-and-orchestra works of the period such as Gabriel Fauré's Ballade, César Franck's symphonic poem Les Djinns and Symphonic Variations—several of these works premiered by Diémer. There was also a growing trend toward similar works by Russian composers. This included Mily Balakirev's First Piano Concerto, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov's sole foray into this genre, and currently lesser-known works as the Allegro de concert in A major by Felix Blumenfeld and the Fantasie russe in B minor by Eduard Nápravník. Tchaikovsky was especially fond of the Nápravník piece and even conducted it. Siloti and Taneyev also performed it.[9]

Once Tchaikovsky finished scoring the Allegro brillante in October 1893, he asked Taneyev to look it over. Taneyev, on whom Tchaikovsky relied for technical pianistic advice, found the solo part lacking in virtuosity. Tchaikovsky had told Siloti that if Taneyev shared his low opinion of the concerto, he would destroy it. The composer did not carry out this threat, however. Tchaikovsky's brother Modest assured Siloti that while Tchaikovsky in no way questioned Taneyev’s verdict, he also had promised the concerto to Diémer and wanted to show the score to him. In fact, on what would be his final visit to Moscow in October 1893, Tchaikovsky showed the concerto once again to Taneyev[10] and still intended to show the work to Diémer.[6]

Less than a month later, Tchaikovsky was dead.

Taneyev gave the first performance of the concerto in Saint Petersburg on January 7, 1895, conducted by Eduard Nápravník.

Questions about the solo part

The piano part has sometimes been called skeletal, and though technically demanding, it has been considered to lack Tchaikovsky's characteristic boldness when compared with his other piano concertos. David Brown suggests this lack of boldness was due to the solo part being incorporated without any attempt to rewrite the musical material originally intended for the Symphony in E-flat.[11] Others have argued that the pianistic texture is often congenial to the keyboard and that the adaption on the whole is well done. They suggest that it is difficult to imagine at which points the piano part takes over material previously intended as part of the orchestral fabric and at which the soloist merely embroiders upon it.[12]

Andante and Finale, Op. posth. 79

Despite his stated intentions, Tchaikovsky had written "End of movement 1" on the last page of the Allegro brillante that would be published by P. Jurgenson as the Third Piano Concerto.[citation needed] At the insistence of the composer's brother Modest, Taneyev began to study the unfinished sketches of the allegro and finale from the E-flat symphony in November 1894. Tchaikovsky had begun to arrange these movements for piano and orchestra but they remained in sketch form. Both Taneyev and Modest questioned how they should be published—as two orchestral movements for a symphony or as a piece for piano and orchestra.[13] After a letter from pianist Alexander Siloti to Modest in April 1895, he and Taneyev took the piano-and-orchestra route. The first performance took place on February 8, 1897 in St. Petersburg with Taneyev as soloist.

According to Tchaikovsky scholar and author John Warrack, accepting Opp. 75 and 79 as a complete concerto within Tchaikovsky's intentions could be a misnomer - "What survives is a reconstruction in concerto form of some music Tchaikovsky was planning, not a genuine Tchaikovsky piano concerto".[14] Music author Eric Blom adds, "It is true that even Taneyev did not know for certain whether Tchaikovsky, if he actually meant to turn out a three-movement concerto, would not have preferred to scrap the Andante and Finale altogether and to replace them by two entirely new movements; so if we decide that the finale at any rate is a poor piece of work, we must blame Taneyev for preserving it rather than Tchaikovsky for having conceived it. For we cannot even be sure how far the conception may have been carried out".[15]

Warrack concludes, "The kindest response is to remember that Tchaikovsky himself abandoned it. Taneyev was being over-pious: much the best solution of the problem of what to do with the music is to perform the Third Concerto as Tchaikovsky left it, in one movement; it could with advantage be heard sometimes in concerts at which soloists wish to add something less than another full-scale concerto to the main work in their program".[16]

"Symphony No. 7"

Notes

- ^ Brown, Man and Music, 414-15.

- ^ Brown, David, Tchaikovsky: The Final Years (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1992), 387-388.

- ^ Warrack, Tchaikovsky Symphonies and Concertos, 47.

- ^ PMC Newsletter, vol. 8 no. 3,April:2001 Archived 2007-02-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Schonberg, Harold C., The Great Pianists (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1987, 1963), 287.

- ^ a b Brown, Final Years, 389.

- ^ As quoted in Brown, Final Years, 389.

- ^ Alexander Poznansky, Tchaikovsky's Last Days (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002), 31-32.

- ^ Evgeny Soifertis, Liner notes for Hyperion compact disc CDA67511.

- ^ Brown, Tchaikovsky: The Final Years, 477.

- ^ Brown, Man and Music, 414; Brown, Final Years, 389.

- ^ Blom, 64-5.

- ^ See letters from Mitrofan Belyayev to Sergei Taneyev from 1896, and from Aleksandr Siloti to Modest Tchaikovsky - Klin House-Museum Archive

- ^ Warrack, Tchaikovsky Symphonies and Concertos, 46.

- ^ Blom, 64

- ^ Warrack, Tchaikovsky Symphonies and Concertos, 47

References

- Blom, Eric, ed. Abraham, Gerald, "Works for Solo Instrument and Orchestra," Music of Tchaikovsky (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1946)

- Brown, David, Tchaikovsky: The Final Years (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1992).

- Brown, David, Tchaikovsky: The Man and His Music (New York: Pegasus Books, 2007). ISBN 978-1-933648-30-9.

- Poznansky, Alexander, Tchaikovsky's Last Days (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996)

- Schonberg, Harold C., The Great Pianists (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1987, 1963)

- Soifertis, Evgeny, Liner notes for Hyperion compact disc CDA67511 (London: Hyperion Records Ltd., 1993)

- Warrack, John, Tchaikovsky (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1973)

- Warrack, John, Tchaikovsky Symphonies and Concertos (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1969)