Reading Company

| |

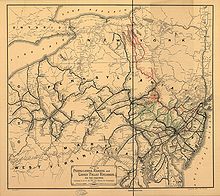

Map of the rail lines of Reading Railroad | |

| |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Headquarters | Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Reporting mark | RDG |

| Locale | Delaware Maryland New Jersey Pennsylvania |

| Dates of operation | 1833–1976 |

| Successor | Conrail (now Norfolk Southern Railway and CSX Transportation) Reading International (cinemas and real estate) |

| Technical | |

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8+1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge |

| Length | 1,460 miles (2,350 kilometres)[1] |

The Reading Company (/ˈrɛdɪŋ/ RED-ing) was a Philadelphia-headquartered railroad that provided passenger and freight transport in eastern Pennsylvania and neighboring states from 1924 until its acquisition by Conrail in 1976.

Commonly called the Reading Railroad and logotyped as Reading Lines, the Reading Company was a railroad holding company for most of its existence, and a single railroad in its later years. It operated service as Reading Railway System and was a successor to the Philadelphia and Reading Railway Company, founded in 1833.

Until the decline in anthracite shipments from the Coal Region in Northeastern Pennsylvania following World War II, it was one of the most prosperous corporations in the United States. Enactment of the federally-funded Interstate Highway System in 1956 led to competition from the modern trucking industry. They used the Interstates for short-distance transportation of goods, which compounded the company's competition for freight business, forcing it into bankruptcy in 1971.

In 1976, its railroad operations merged into Conrail, and the remainder of the corporation was renamed Reading International.

History

Philadelphia and Reading Rail Road: 1833–1893

The Philadelphia and Reading Rail Road (P&R) was one of the first railroads in the United States. Along with the Little Schuylkill, a horse-drawn railroad in the Schuylkill River Valley, it formed the earliest components of what became the Reading Company. The P&R was constructed initially to haul anthracite coal from the mines of the Coal Region in Northeastern Pennsylvania to Philadelphia.[2] The original P&R mainline extended south from the mining town of Pottsville to Reading and then to Philadelphia. The right of way needed only gentle grading to follow the banks of the Schuylkill River for nearly all of the 93-mile (150-km) journey.[2][3] From its founding in 1843, the original Reading mainline was a double track line.

The P&R became profitable almost immediately. Energy-dense coal, known as anthracite, had been replacing increasingly scarce wood as fuel in businesses and homes since the 1810s, and P&R-delivered coal was one of the first alternatives to the near monopoly held by Lehigh Coal & Navigation Company since the 1820s. The P&R bought or leased many of the railroads in the Schuylkill River Valley and extended westward and north along the Susquehanna River into the southern portion of the Coal Region.

In Philadelphia, the Reading built Port Richmond, the self-proclaimed "largest privately-owned railroad tidewater terminal in the world",[3] which burnished the P&R's bottom lines by allowing anthracite coal to be loaded onto ships and barges for export. In 1871, the Reading established a subsidiary, the Philadelphia and Reading Coal and Iron Company, which set about buying anthracite coal mines throughout the Coal Region.

This vertical expansion gave the P&R almost full control of the region's anthracite coal market, including both its mining and transport, allowing it to compete successfully with competitors such as the Lehigh Coal and Navigation Company and the Delaware and Hudson Canal Company.

The company's heavy investment in anthracite coal paid off quickly. By 1871, the Reading was the largest company in the world with $170,000,000 in market capitalization (equal to $4,323,666,667 today).[4] It may have been the first conglomerate in the world.

In 1879, the Reading gained control of the North Pennsylvania Railroad, which provided access to the burgeoning steel industry in the Lehigh Valley.[3]

The Reading further expanded its coal empire into New York City by gaining control of the Delaware and Bound Brook Railroad in 1879, and building the Port Reading Branch in 1892 with a line from Port Reading Junction to Port Reading, New Jersey on the Arthur Kill. This allowed direct delivery of coal to industries to the Port of New York and New Jersey in North Jersey and New York City by rail and barge instead of the longer trip by ships from Port Richmond around Cape May.

Instead of broadening its rail network, the Reading invested its vast wealth in anthracite and its transportation in the mid-19th century. In 1890, however, Reading president Archibald A. McLeod concluded that expanding the company's rail network and becoming a trunk railroad would prove more lucrative than anthracite mining.

The following year, in 1891, McLeod began attempting to seize control of neighboring railroads and successfully gained control of the Lehigh Valley Railroad, Central Railroad of New Jersey, and the Boston and Maine Railroad. The Reading almost achieved its goal of becoming a trunk railroad, but the deal was scuttled by J. P. Morgan and other rail barons who did not want more competition in the northeastern railroad business.[2][5] The Reading was relegated to being a regional railroad for the rest of its history.

1833–1873: General Expansion

The Philadelphia and Reading Rail Road was chartered on April 4, 1833, to build a line along the Schuylkill River between Philadelphia and Reading. The portion from Reading to Norristown opened July 16, 1838, and the full line opened December 9, 1839. Its Philadelphia terminus was at the state-owned Philadelphia and Columbia Railroad (P&C) on the west side of the Schuylkill River from where it ran east on the P&C over the Columbia Bridge and onto the city-owned City Railroad to a depot at the southeast corner of Broad and Cherry Streets in Center City Philadelphia.

An extension northwest from Reading to Mount Carbon, also on the Schuylkill River, opened on January 13, 1842, allowing the railroad to compete with the Schuylkill Canal. At Mount Carbon, it connected with the earlier Mount Carbon Railroad, continuing through Pottsville to several mines, and would eventually be extended to Williamsport.[6][7][when?] On May 17, 1842, a freight branch from West Falls to Port Richmond on the Delaware River north of downtown Philadelphia opened. Port Richmond later became a very large coal terminal.

On January 1, 1851, the Belmont Plane on the Philadelphia and Columbia Railroad, just west of the Reading's connection, was abandoned in favor of a new bypass, and the portion of the line east of it was sold to the Reading, the only company that continued using the old route.

The Lebanon Valley Railroad was chartered in 1836 to build from Reading west to Harrisburg. Reading financed the construction of the Rutherford Yard to compete with the PRR's nearby Enola Yard. The Reading took it over and began construction in 1854, opening the line in 1856. This gave the Reading a route from Philadelphia to Harrisburg, for the first time to compete directly with the Pennsylvania Railroad, which became its major rival.

In 1859, the Reading leased the Chester Valley Railroad, providing a branch from Bridgeport west to Downingtown. It had formerly been operated by the Philadelphia, Germantown and Norristown Railroad.

A new Philadelphia terminal opened on December 24, 1859, at Broad and Callowhill Streets, north of the old one at Cherry Street. The Reading and Columbia Railroad was chartered in 1857 to build from Reading southwest to Columbia on the Susquehanna River. It opened in 1864, using the Lebanon Valley Railroad from Sinking Spring east to Reading. The Reading leased it in 1870.

The early Philadelphia and Reading Railroad named all of its locomotives with names such as Winona or Jefferson, as did most American railroads following in the British precedent, but in December 1871 the P&R replaced all the names with numbers.[8] The Port Kennedy Railroad, a short branch to quarries at Port Kennedy, was leased in 1870. Also that year, the Reading leased the Pickering Valley Railroad, a branch running west from Phoenixville to Byers, Pennsylvania, which opened in 1871.

On December 1, 1870, the Reading leased the Philadelphia, Germantown and Norristown Railroad, thereby gaining that company's route along the east bank of the Schuylkill from Philadelphia to Norristown, as well as its branch to Chestnut Hill.[9]

1873: Chester Branch

In 1873, the P&R extended its reach southward by leasing 10.2 miles of track from the Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore Railroad. Dubbed the Philadelphia & Chester Branch, the line extended from the Gray's Ferry Bridge across the Schuylkill River in West Philadelphia to Ridley Creek in Ridley Park in Delaware County.[10] The segment included 4.9 miles of double track and 16.7 miles of single track, including sidings and turnouts.[11]

The segment was part of the original 1838 line of the PW&B, which in 1872 opened a new stretch of track further inland to serve more populated areas and reduce flooding. On July 1, 1873, the PW&B agreed to lease the freight rights to the P&R for "$350,000 payable at the time the lease was made and $1 a year thereafter"[10] for a term of 999 years with the stipulation that no passenger trains would use it.[12] The Reading dubbed the line, along with some connecting track, its Philadelphia and Chester Branch;[13] southbound trains reached it via the Junction Railroad, jointly controlled by PW&B, Reading, and PRR, and continued on to the connecting Chester and Delaware River Railroad.

1875–1893: Competition

During 1875, four members of the Camden and Atlantic Railroad board of directors resigned to build a second railroad from Camden, New Jersey, to Atlantic City by way of Clementon. Led by Samuel Richards, an officer of the C&A for 24 years, they established the Philadelphia and Atlantic City Railway (P&AC) on March 24, 1876. A 3-foot-6-inch narrow gauge was selected because it would lower track laying and operating costs. Work began in April 1877, and the track work was completed in a remarkable 90 days.

On July 7, 1877, the final spike was driven and the 54.67 miles (87.98 km) line was opened in time for the summer tourism season. However, on July 12, 1878, the P&AC Railway slipped into bankruptcy; on September 20, 1883, it was jointly acquired by the Central Railroad of New Jersey (CNJ) and the Philadelphia and Reading Railway for $1 million. The name was changed to Philadelphia and Atlantic City Railroad on December 4, 1883. The first major task was to convert all track to standard gauge, which was completed on October 5, 1884. The Philadelphia and Reading Railway acquired full control on December 4, 1885.

The Reading leased the North Pennsylvania Railroad on May 14, 1879. This gave it a line from Philadelphia north to Bethlehem, and also the valuable Delaware and Bound Brook Railroad, the descendant of the National Railway project, providing a route to New York City in direct competition with the Pennsylvania Railroad's United New Jersey Railroad and Canal Company. At the New York end, it used the Central Railroad of New Jersey's Jersey City Terminal from which passengers could board ferries to Liberty Street Ferry Terminal, Staten Island Ferry Whitehall Terminal, and West 23rd Street in Lower Manhattan.[14]

The Reading Terminal opened in Philadelphia in 1893. On May 29 the Reading leased the Central Railroad of New Jersey. The Reading eventually bought a majority of the CNJ's stock in 1901.

On April 1, 1889, the Philadelphia and Reading Railway consolidated the Philadelphia and Atlantic City Railway, Williamstown & Delaware River Railroad, Glassboro Railroad, Camden, Gloucester and Mt. Ephraim Railway, and the Kaighn's Point Terminal Railroad in southern New Jersey into The Atlantic City Railroad. The Port Reading Railroad was chartered in 1890 and opened in 1892, running east from a junction from the New York main line near Bound Brook to the Port Reading on the Arthur Kill near Perth Amboy.

The Lehigh Valley Railroad was leased on December 1, 1891, under the presidency of Archibald A. McLeod, but that lease was canceled on August 8, 1893, when the Reading went into receivership, an event associated with the Panic of 1893. The Reading also relinquished control of the Central New England Railway and the Boston and Maine Railroad. Amid the turmoil of the Panic of 1893, Joseph Smith Harris was elected president. Under his leadership, the Reading Company was formed and the P&R was absorbed into it on November 30.[15] Also in 1893, the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad built its most famous structure, Reading Terminal in Philadelphia, which served as the terminus for most of its Philadelphia-bound trains, and also the company's headquarters.[5]

1877: Reading Railroad Massacre

On July 22, 1877, after the crushing of strikes and unions by the Philadelphia and Reading Railway, and following in the path of the Great Railroad Strikes of 1877, vandalism of the Reading's financial interests in Reading, Pennsylvania began. The subsidiary that owned mining interests in the area, the Philadelphia and Reading Coal and Iron Company, not the government, called up militia and Coal and Iron Police to put down riots and protests that had broken out in the city. After the militia and Coal and Iron Police went to retrieve a train carrying coal that was blocked in a railroad cut, they fired on rioters and protesters, killing at least 10 and wounding more than 40.

Philadelphia and Reading Railway: 1896–1923

After the Panic of 1893, and the failure of Archibald A. McLeod's efforts to turn the Reading into a major trunk line, the Reading was forced to reorganize under suspicions of monopoly. The Reading Company was created to serve as a holding company for the Reading's rail and coal subsidiaries: the Philadelphia and Reading Railway, and the Philadelphia and Reading Coal and Iron Company, respectively.[16] However, in 1906, with the support of the Roosevelt Administration, the Hepburn Act was passed. This required all railroads to disinvest themselves of all mining properties and operations, and so the Reading Company was forced to sell the P&R Coal and Iron Company.[2]

Whether an actual monopoly or not, the company's history as the Reading Railroad over a century ultimately became immortalized as a featured property on the original Monopoly game board.

Even though moving and mining of coal was its primary business, the P&R eventually became more diversified through the development of many on-line industries, averaging almost five industries per mile of main line at one point, and the expanding role of the Reading as a bridge route.

This included its important role on the Alphabet Route, from Boston and New York City to Chicago with traffic from the Lehigh Valley Railroad and Central Railroad of New Jersey entering the Reading System in Allentown, traveling over the East Penn Branch to Reading, where trains then traveled west over the Lebanon Valley Branch to Harrisburg and then onward over the Philadelphia, Harrisburg and Pittsburgh branch, or PH&P to Shippensburg, Pennsylvania where trains connected with the Western Maryland Railroad to continue westward. This route became known as the Crossline, and the Reading started to pool locomotive power between its connecting railroads to provide a more seamless transfer of freight and passengers.[5]

Even though the Reading was never again to regain its powerful position of the 1870s, it still was a very profitable and important railroad. From the turn of the 20th century to the outbreak of World War I, the Reading was among the most modern and efficient railroads. In keeping with the standards of much larger railroads, The Reading embarked on many improvement projects which typically were not attempted by smaller railroads. This included triple and quadruple tracking many of its major routes, improving signaling and track quality, as well as expanding system capacity and station facilities.[5]

The Reading invested in the construction of new cut-offs, bypasses and connections, much like the Pennsylvania Railroad's low-grade lines and the Lackawanna Cut-off. The completion of the Reading belt line in 1902, a 7.2-mile westerly bypass of downtown Reading, alleviated the heavy rail congestion in the busy city.[2][17]

In Bridgeport, a new bridge was constructed over the Schuylkill River in 1903. The bridge connected the P&R main line on the west (south) bank of the river with the Manayunk/Norristown Line on the opposite side, allowing passenger service to Norristown and a bypass of the old main line, known as the West Side Freight line.[2]

The Ninth Street Branch—the main thoroughfare into Reading Terminal—was also improved. Between 1907 and 1914 the old double-track and street-level route was replaced by an elevated quadruple-track route that offered greater capacity and safety.[3] In 1901, the Reading gained a controlling interest in the Central Railroad of New Jersey, allowing the Reading to offer seamless, one-seat rides from Reading Terminal in Philadelphia to the Central New Jersey's Jersey City Communipaw Terminal by way of Bound Brook onto the Central New Jersey mainline. The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad was also looking for access to the New York City market, and in 1903 it gained control over the Reading and ensured track rights over the Reading and Central New Jersey to Jersey City.[18]

To the north, the New York Short Line was completed in 1906, and was a cut-off for New York City-bound trains through freights and the Baltimore and Ohio's Royal Blue.[5]

Reading Shops

The first locomotive and car repair shops were built in 1850 at Reading, Pennsylvania, consisting of two enclosed roundhouses and a machine shop. In 1902, the Reading Shops were materially expanded and overhauled into new property on the north side along the Reading yards and North 6th Street, facilitating the maintenance and construction of a greater locomotive and rolling stock fleet. The shops were completed four years later; with their imposing brick architecture, they were among the largest railroad shops in the US. Unlike most railroads, the Reading Shops were able to fabricate locomotives, freight cars, and passenger cars in addition to regular overhauls and repairs. The locomotive department employed an average of 2,000 workers, featuring a machine shop containing 70 erecting pits, while the car department employed an additional 1,000. Other car shops were kept busy at Wayne Junction (Philadelphia), St. Clair/Pottsville, Tamaqua, Newberry Junction (Williamsport), and Rutherford, outside of Harrisburg.[19] Most of the former Reading shops still stand today in non-railroad use.[2]

Larger steam locomotives were introduced to haul the increasing traffic, including the massive N1 class 2-8-8-2 (Chesapeake) Mallet, and Reading made one M1 class 2-8-2 freight hauler; Baldwin Locomotive Works built the rest. Big freight haulers were the massive K-1 2-10-2 locomotives; some were built in Reading from the Mallets; others were built by Baldwin. The G1 class 4-6-2 were passenger locomotives. These classes were an important break of tradition of the Reading's motive power fleet.

The M1s were the first Reading locomotives to include a trailing truck, and the first engine with the cab behind the Wootten firebox. Engines with the name "lessor" in its title meant some steam power was owned by a second party and leased to the P&R. The G1s were the first Reading passenger locomotives with three-coupled driving wheels.[2]

Between 1945 and 1947, the company took 30 class I-10 2-8-0 locomotives and rebuilt them at the 6th Street facility into the modern T1 class 4-8-4 locomotives for 6 million dollars. This was a move to offset the fact that EMD FT diesel locomotives (the first choice of Reading management) were very hard to obtain, but the Reading needed faster, up-to-date modern power. The steamers never ran long enough to pay back this major investment, and had some major problems, but it did keep men employed. As of 2023, four examples have survived, and the 2102 is in active tourist service with the Reading, Blue Mountain and Northern Railroad. The Reading built or bought numerous smaller 4-4-0s, 2-8-0s and switchers for its fleet.[20]

Passenger operations

The Reading Company did not operate extensive long-distance passenger train service, but it did field several named trains, most famous of which was the streamlined Crusader, which connected Philadelphia and Jersey City, New Jersey.

Other trains in the fleet included the Harrisburg Special (between Jersey City and Harrisburg, Pennsylvania), King Coal (between Philadelphia and Shamokin, Pennsylvania), North Penn (between Philadelphia and Bethlehem, Pennsylvania), Queen of the Valley (between Jersey City and Harrisburg), Schuylkill (between Philadelphia and Pottsville, Pennsylvania), and Wall Street (between Philadelphia and Jersey City).[2] The Reading participated in the joint operation of The Interstate Express with the Central Railroad Company of New Jersey and the Delaware, Lackawanna & Western Railroad, with service between Philadelphia and Syracuse, New York.[21]

Reading also offered through passenger car service with the Lehigh Valley Railroad via their connection at Bethlehem. Like most railroads, the Reading had contracts with the U.S. Post Office to haul and sort mail en route. After World War II, the Reading looked at dropping the mail and in 1961 notified the government that it intended to stop mail service on its passenger trains. On July 1, 1963, the post office let them out of the contracts, which were valued at $2,137,000, equal to $21,267,796 today, and the railroad switched to Budd RDC self-propelled cars, instead of locomotive hauled passenger trains, to save money.[22]

Camden-Atlantic City speed: On July 20, 1904, regularly-scheduled train no. 25, running from Kaighn's Point in Camden, New Jersey to Atlantic City with Philadelphia and Reading Railway class P-4c 4-4-2 (Atlantic class cab over boiler) locomotive No.334 and 5 passenger cars, set a speed record. It ran the 55.5 miles in 43 minutes at an average speed of 77.4 mph. The 29.3 miles between Winslow Jct and Meadows Tower (outside of Atlantic City) were covered in 20 minutes at a speed of 87.9 mph. During the short segment between Egg Harbor and Brigantine Junction, the train was reported to have reached 115 mph.[23]

The Reading operated an extensive commuter network out of Reading Terminal in Philadelphia. In the late 1920s, most of the suburban system was electrified (the first lines electrified were the Ninth Street Branch, New Hope Branch as far as the Hatboro station and extended to Warminster station in 1974, the Bethlehem Branch as far as Lansdale, the Doylestown Branch, and the New York Branch to West Trenton).[24] Reading ordered 150 electric multiple units from Bethlehem Steel which were supplemented by twenty unpowered coach trailers converted from existing coaches[25] and electrified services began on July 26, 1931.[24]

Reading Company: 1924–1976

After the First World War with the release of the Reading from government control, they decided to streamline their corporate structure. For twenty years the Reading Company, the holding company created for the P&R and the P&R Coal and Iron Company, only controlled the P&R after the sale of the P&R Coal and Iron Company. To simplify corporate structure, the P&R ceased operation in 1924 and the Reading Company took over operating the railroad.[26]

The period just after World War I may have been the Reading Company's best with traffic on the Reading at its peacetime high. Annual volume was about 15 million tons of anthracite, 25 million tons of bituminous coal with a further 30 million tons of industrial traffic.[3] The Reading had taken great strides to wean itself of anthracite dependency but it still relied heavily on coal revenue, and Pennsylvania anthracite production had peaked in 1917 with 99.7 million tons produced.[27]

| Reading | Cornwall | B&S | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1925 | 6,775 | 9 | 0.8 |

| 1933 | 3,943 | 3 | (incl in RDG) |

| 1944 | 9,303 | 13 | |

| 1960 | 5,685 | 8 | |

| 1970 | 4,329 | (incl in RDG) |

| Reading | Cornwall | B&S | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1925 | 418 | 0.6 | 0.6 |

| 1933 | 150 | 0.01 | (incl in RDG) |

| 1944 | 541 | 0 | |

| 1960 | 173 | 0 | |

| 1970 | 195 | (incl in RDG) |

The 1925 "Reading" totals above include all the subsidiaries (C&F, G&H, P&CV etc.) that were operating roads in 1925 but whose totals were included in Reading's after 1929. None of the totals include Atlantic City RR or PRSL.

Commuter lines

In the 1920s, the Reading operated a dense network of commuter lines branching off of the Ninth Street Branch mostly powered by small 4-4-0s, 4-4-2s and 4-6-0 camelbacks.

Bankruptcy protection

The Reading Company was forced to file for bankruptcy protection in 1971.[28] The bankruptcy was a result of dwindling coal shipping revenues, freight being diverted to highways by trucking companies, and strict government regulations that denied railroads the ability to set prices, imposed high taxes, and forced the railroads to continue to operate money-losing lines as a common carrier.[citation needed]

Electrification

The railroad also had an extensive commuter operation centered around Philadelphia, the hub of which was Reading Terminal. The following suburban lines were electrified during the onset of the Great Depression:

- Norristown Line

- Chestnut Hill

- Lansdale/Doylestown

- Hatboro (extended to Warminster in 1974)

- West Trenton

The notable exception was the Fox Chase/Newtown branch. With the aid of public funding from the city of Philadelphia, the line was electrified as far as Fox Chase (the last station within city limits) in September 1966.[29]

Electrification was to be completed through to Newtown in the 1970s, but government subsidies were not readily available, leaving the Fox Chase-Newtown section as the lone non-electrified suburban commuter route on the Reading system. Passenger service between Fox Chase and Newtown was terminated on January 14, 1983, under the auspices of SEPTA.

To further complicate matters, the Reading was forced to continue paying its debts to the Penn Central Railroad, however, Penn Central (also in bankruptcy at the time) was not required to pay its debts to the Reading Company.

Post-railroad: 1976–present

| Company type | Public |

|---|---|

| Nasdaq: RDI (Non-Voting Class A) Russell 2000 Index component | |

| Subsidiaries | Reading Cinemas Consolidated Theatres |

| Website | www |

On April 1, 1976, the Reading Company sold its railroad assets to the newly formed Consolidated Railroad Corporation (Conrail), leaving it with 650 real estate assets, some coal properties, and 52 abandoned rights-of-way. As of 1999, most former Reading lines are now part of Norfolk Southern Railway (NS), as a result of the Conrail split between NS and CSX Transportation. It had sold 350 of the real estate tracts by the time it left bankruptcy in 1980.[citation needed]

In the late 1980s, a Los Angeles-based lawyer, James Cotter, gained control of the corporation through his holding company, the Craig Corporation, and used its assets to finance his movie theater chains in Puerto Rico, Australia, and New Zealand. In 1991, the company sold one of its last railroad-related assets, the Reading Terminal Headhouse. Five years later, in 1996, Cotter reorganized the company as Reading Entertainment. On December 31, 2001, both Reading Entertainment and Craig Corporation merged into and with Citadel Holding Corporation, another Cotter company.[30]

The successor company was renamed Reading International Inc. with two classes of stock: Non-Voting Class A shares (NASDAQ: RDI) and Voting Class B shares (NASDAQ: RDIB).[31]

Preserved steam locomotives

A total of nine steam locomotives that once served the company are still preserved.

- 0-4-0 1 Rocket - Built by the Braithwaite, Milner and Company in London in 1838. It is the oldest preserved locomotive of the railroad. It currently resides at the Railroad Museum of Pennsylvania in Strasburg. [32]

- 4-4-0 3 Shamokin - Built by the Eastwick and Harrison Company in 1842. It is the only surviving 4-4-0 of the Reading Company. It currently resides at the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia.[33]

- 2-2-2 tank Black Diamond - Built by the Baldwin Locomotive Works in 1889. It is the only known surviving inspection locomotive in the United States. Currently on loan to the National Museum of Transportation in St. Louis, Missouri.[34]

- 0-4-0 camelback 1187 - Built by the Baldwin Locomotive Works in 1903. It is the last surviving Reading camelback locomotive. It currently resides at the Age of Steam Roundhouse in Sugarcreek, Ohio.

- 0-6-0 tank 1251 - Built by the Reading's own locomotive shops in 1918. It was the only tank engine to be rostered by the Reading after World War I. It currently resides at the Railroad Museum of Pennsylvania in Strasburg.

- 4-8-4 2100 - Built by the Baldwin Locomotive Works in 1923, rebuilt by the Reading in 1945. It is the prototype engine of the Reading's T-1 class. It currently resides at the Ex-Baltimore and Ohio roundhouse in Cleveland, where it is currently being restored to operation.

- 4-8-4 2101 - Built by the Baldwin Locomotive Works in 1923, rebuilt by the Reading in 1945. It currently resides at the B&O Railroad Museum in Baltimore.

- 4-8-4 2102 - Built by the Baldwin Locomotive Works in 1923, rebuilt by the Reading in 1945. It currently resides at the Reading Blue Mountain and Northern Railroad in Port Clinton. It was restored to running condition and is in operation

- 4-8-4 2124 - Built by the Baldwin Locomotive Works in 1924, rebuilt by the Reading in 1947. It currently resides at Steamtown National Historic Site in Scranton.

Major named passenger trains

Major named passenger trains associated with the Reading line include:

- Crusader: Jersey City to Philadelphia (Reading Terminal) via West Trenton

- King Coal: Philadelphia to Shamokin via Reading (Reading Franklin Street Terminal) and Pottsville on the Reading's Main Line

- Main Line: to Pottsville

- North Penn: Philadelphia to Bethlehem, Pennsylvania

- Queen of the Valley (eastbound: called Harrisburger): Jersey City to Harrisburg (Harrisburg Central Station, also known as Pennsylvania Station)

- Scranton Flyer: to Scranton

- Wall Street: Philadelphia to Jersey City

In conjunction with other railroads:

- Interstate Express: to Syracuse (with the Lackawanna Railroad and the Central Railroad of New Jersey)

- Maple Leaf: to Toronto via Buffalo (with the Lehigh Valley Railroad)

Heritage units

As a part of Norfolk Southern's 30th anniversary in 2012, the company painted 20 new locomotives into predecessor schemes. NS #1067, an EMD SD70ACe locomotive, was painted into the Bee Line Service paint scheme of the Reading. In 2023, it received a fresh coating of paint.

In 2024, SEPTA unveiled two Silverliner IV heritage units, to celebrate the cars' 50th Anniversary. Numbers 280 and 293 were selected as two ex-Reading cars which were stripped bare and put back into their 1974 as-delivered Reading Company look.

Company officers

The presidents of the Reading Company were:

- Elihu Chauncey – 1834–1842

- William F. Emlen – 1842–1843

- John Cryder – 1843–1970

- John Tucker – 1844–1856

- Robert D. Cullen – 1856–1860

- Asa Whitney – 1860–1861

- Charles Eastwick Smith – 1861–1869

- Franklin B. Gowen – 1869–1884

- Frank S. Bond – 1881–1882

- George DeBenneville Keim – 1884–1887

- Austin Corbin – 1887–1890

- Archibald A. McLeod – 1890–1893

- Joseph Smith Harris – 1893–1901

- George Frederick Baer – 1901–1914

- Theodore Voorhees – 1914–1916

- Agnew Dice – 1916–1932

- Charles H. Ewing – 1932–1935

- Edward W. Scheer – 1935–1944

- Revelle W. Brown – 1944–1952

- Joseph A. Fisher – 1952–1960

- E. Paul Gangewere – 1960–1964

- Charles E. Bertrand – 1964–1976

In popular culture

The Reading Railroad is one of the four railroads that can be bought in the original version of the board game Monopoly.

See also

Gallery

- Philadelphia and Reading Railroad daily passenger train time table, 1854

- Gold Bond of the Reading Company, issued June 19, 1902

- Reading Railroad system map, 1923

Notes

- ^ Drury, George H. (1994). The Historical Guide to North American Railroads: Histories, Figures, and Features of more than 160 Railroads Abandoned or Merged since 1930. Waukesha, Wisconsin: Kalmbach Publishing. pp. 275–277. ISBN 0-89024-072-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Plant (1996).

- ^ a b c d e Pennypacker (2002), p. 38.

- ^ Reading Railroad

- ^ a b c d e Plant (1998).

- ^ Williamsport is located at 41°14′40″N 77°1′7″W / 41.24444°N 77.01861°W (41.244428, −77.018738),"US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011. and is bordered by the West Branch Susquehanna River to the south... As the crow flies, Williamsport in Lycoming County is about 130 miles (209 km) northwest of Philadelphia and 165 miles (266 km) east-northeast of Pittsburgh.

- ^ "2007 General Highway Map Lycoming County Pennsylvania" (PDF) (Map). 1:65,000. Pennsylvania Department of Transportation, Bureau of Planning and Research, Geographic Information Division. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 5, 2011. Retrieved December 27, 2009.

- ^ Bernhart (2006), p. 3.

- ^ Holton (1989), p. 279.

- ^ a b Basalik, Kenneth J. & Philip Ruth (March 2, 2015). "Philadelphia & Reading Railroad: Chester Branch" (PDF). Historic Resource Survey Form. PENNSYLVANIA HISTORICAL AND MUSEUM COMMISSION, Bureau for Historic Preservation. Retrieved April 27, 2016.

- ^ "Report of the Operations of the Philadelphia & Reading Railroad Co. and the Philadelphia & Reading Coal & Iron Co". Philadelphia & Reading Railroad Co. 1881. Retrieved April 27, 2016.

- ^ Morlok, Edward K., University of Pennsylvania (2005). "First Permanent Railroad in the U.S. and Its Connection to the University of Pennsylvania." Archived April 2, 2005, at the Wayback Machine Transportation Data. Accessed April 23, 2013.

- ^ "The Railway World". United States Railroad and Mining Register Company. January 1, 1880 – via Google Books.

- ^ Railroad Ferries of the Hudson: And Stories of a Deckhand, by, Raymond J. Baxter, Arthur G. Adams, pg. 45–60, 1999, Fordham University Press, 978-0823219544

- ^ Holton (1989), p. 339.

- ^ "Home Page - Reading Railroad Heritage Museum - Reading Company Technical & Historical Society". www.readingrailroad.org. Archived from the original on September 23, 2008.

- ^ Reading Eagle Quote: “1902: Reading Belt Line, which runs through West Reading and bypasses the city, is dedicated, 1900: Construction of new rail shops in Reading begins” ret>6/17/09

- ^ "Philadelphia NRHS – Reading". Trainweb.org. Retrieved July 29, 2010.

- ^ Starr, Timothy. (2022). The Back Shop Illustrated, Vol. 1.

- ^ "Reading Steam roster". Northeast.railfan.net. Retrieved July 29, 2010.

- ^ Greenberg, Jr., William T. "The Interstate Express" Railroad Model Craftsman, August 2003: pp. 86–97.

- ^ READING EAGLE NEWSPAPER thurs.2-13-63."The Erie-Lackawanna Limited". Generaljim1-ivil.tripod.com. Archived from the original on July 28, 2010. Retrieved July 29, 2010.

- ^ Camden-Atlantic City Line speed : (Howden,_Boys'_Book_of_Locomotives,_1907).jp

- ^ a b Williams 1998, p. 47

- ^ Coates 1990, p. 23

- ^ Alecknavage II, Albert (June 12, 2002). "Reading Company History". Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S.: The Philadelphia Chapter of the National Railway Historical Society. Retrieved July 17, 2009.

After World War One, it became desirable for the P&R to simplify its corporate structure. The Reading Company, which had existed earlier as a holding company, became an operating company in 1923. Many previously-leased railroads which the Philadelphia & Reading RR had taken over—as well as the original P&R itself—were now providing service as the Reading Company.

- ^ Waston, Kathie (September 16, 1997). "The Use of Historical Production Data to Predict Future Coal Production Rates". USGS. Retrieved July 18, 2009.

70-year long period of rapid growth until 1917, when annual production reached 99.7 million tons during World War I

- ^ Treese, Lorett (2003). Railroads of Pennsylvania: fragments of the past in the Keystone landscape. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books. p. 114. ISBN 978-0-8117-2622-1. OCLC 50228411.

- ^ "Light Rail Now.org". Light Rail Now.org. Retrieved July 29, 2010.

- ^ "AMENDMENT #3 TO SCHEDULE 13E-3". Securities and Exchange Commission.

- ^ "FORM 425". Securities and Exchange Commission.

- ^ "The Franklin Institute's antique Reading Railroad train has left Philly". August 15, 2023.

- ^ "RDG Co. Surviving Steam Profile". www.readingrailroad.org. Retrieved March 22, 2022.

- ^ "RDG Co. Surviving Steam Profile". www.readingrailroad.org. Retrieved March 22, 2022.

References

- Holton, James L. (1989). The Reading Railroad: History of a Coal Age Empire : The Nineteenth Century. Vol. 1. Laury's Station, PA: Garrigues House. ISBN 0-9620844-1-7.

- Williams, Gerry (1998). Trains, Trolleys & Transit: A Guide to Philadelphia Area Rail Transit. Piscataway, New Jersey: Railpace Company. ISBN 978-0-9621541-7-1.

Further reading

- Bernhart, Benjamin L. (2006). Reading Railroad: Steam in Action. Vol. 2. Outer Station Project. ASIN B008I5LKEO.

- Coates, Wes (1990). Electric trains to Reading Terminal. Flanders, NJ: Railroad Avenue Enterprises. OCLC 24431024.

- Holton, James L. (1992). The Reading Railroad: History of a Coal Age Empire: The Twentieth Century. Vol. 2. Laury's Station, PA: Garrigues House. ISBN 0-9620844-3-3.

- Losse, Bobb (January 1994). Reading Company Freight Cars: Volume 1, Covered Hopper Cars. Lumberton, NJ: David Carol Publications. ISBN 978-1-8825-5901-5.

- Pennypacker, Bert (2002). Reading Company in Color Volume 2. Scotch Plains, New Jersey: Morning Sun Books Inc. ISBN 1-58248-079-6.

- Plant, Jeremy F (1996). Reading Steam in Color, Volume 1. Edison, New Jersey: Morning Sun Books Inc. ISBN 1-878887-70-X.

- Plant, Jeremy F. (1998). Reading Company in Color, Volume 1. Edison, New Jersey: Morning Sun Books, Inc. ISBN 1-878887-95-5.

- Reading Company (1958). Building a Modern Railroad. Reading Company. OCLC 17181292.

External links

- Reading Company Technical and Historical Society

- North East Rails (Reading to Pottsville, Pennsylvania and the Anthracite Coal Region of Schuylkill County, Pennsylvania)

- http://www.schuylkillhavenhistory.com

- Reading Company photograph collection (1873–1945) at Hagley Museum and Library

- Reading Company photographs (circa 1984–1960) at Hagley Museum and Library

- PRR Chronology Archived September 30, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- SEC filings of Reading Entertainment Inc.

- SEC filings of Reading International Inc.

- Reading Company employment and real estate records