People's National Movement

| Part of a series on |

| Liberalism |

|---|

|

The People's National Movement (PNM) is the longest-serving and oldest active political party in Trinidad and Tobago. The party has dominated national and local politics for much of Trinidad and Tobago's history, contesting all elections since 1956 serving as the nation's governing party or on four occasions, the main opposition. It is one out of the country's two main political parties.[5][6][7] There have been four PNM Prime Ministers and multiple ministries. The party espouses the principles of liberalism[8][9][10][11][12] and generally sits at the centre[13][14][15] to centre-left[16][17] of the political spectrum.

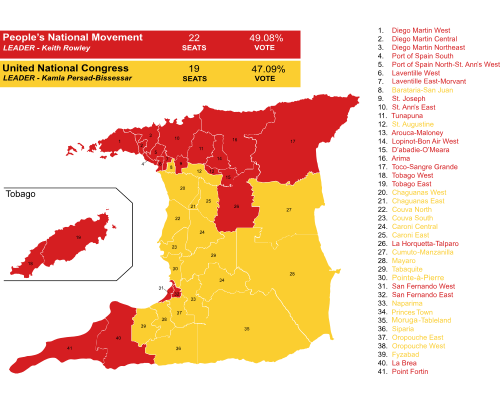

The party was founded in 1956 by Eric Williams, who took inspiration from Norman Manley's democratic socialist centre-left People's National Party in Jamaica.[18][19] It won the 1956 General Elections and went on to hold power for an unbroken 30 years. After the death of Williams in 1981, George Chambers led the party. The party was defeated in the 1986 General Elections, losing 33–3 to the National Alliance for Reconstruction (NAR). Under the leadership of Patrick Manning, the party returned to power in 1991 following the 1990 attempted coup by the Jamaat al-Muslimeen, but lost power in 1995 to the United National Congress (UNC). The PNM lost again to the UNC in the 2000 General Elections, but a split in the UNC forced new elections in 2001. These elections resulted in an 18–18 tie between the PNM and the UNC, and President Arthur N. R. Robinson appointed Manning as Prime Minister. Manning was unable to elect a Speaker of the House of Representatives, but won an outright majority in new elections held in 2002 and again in 2007, before losing power in 2010. It returned to power in the 2015 general election under Keith Rowley where it had its best result since the 1981 general election, winning 51.7 percent of the popular vote and 23 of the 41 seats. In the 2020 general election, they won the popular vote and a majority in the House of Representatives, winning 22 seats.

The party symbol is the balisier flower (Heliconia bihai) and the Party's political headquarters is known as the "Balisier House" located in Port of Spain. Historically, the PNM has been supported by a majority of Afro-Trinidadians and Tobagonians and the Creole-Mulatto population,[20][21] thus it is colloquially called the Black Party, the African Party, or the Creole Party.[22][23][24][25] The PNM has its strongest support in cities and urban areas.[26] It was also historically supported by different minorities such as the Chinese, Christian Indians (other than Presbyterian Indians), and Muslims of any ethnicity of the country.[27][28][20][21]

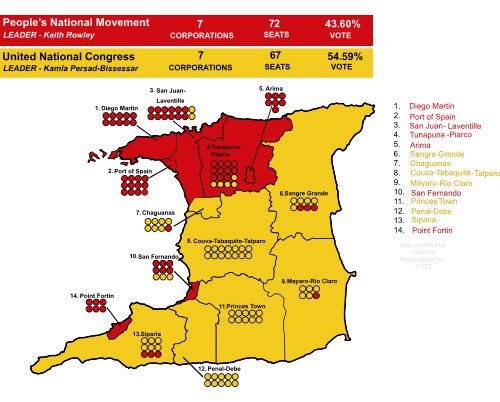

The PNM's signature policies and legislative decisions include independence, writing the Constitution of Trinidad and Tobago, republicanism, the establishment of the Tobago House of Assembly, the Public Transport Service Corporation, the Water Taxi Service, universal preschool, primary and secondary education, universal health care, criminalizing child marriage and decriminalizing cannabis.[29][30][31][32] In government since the 2015 general election, the party holds an overall majority of 22 out of 41 Members of Parliament in the House of Representatives and 16 out of 31 members of the Senate. The party has 72 out of the 139 local councillors and is in control of seven of the 14 regional corporations since the 2019 Trinidadian local elections. The party also has one out of 12 assembly members in the Tobago House of Assembly since the December 2021 Tobago House of Assembly elections.

Despite not being a socialist party, the PNM was a member of the democratic socialist West Indies Federal Labour Party in the Federal Parliament of the West Indies Federation from 1957 to 1962. The party includes a semi-autonomous Tobagonian branch known as the Tobago Council of the People's National Movement. As of September 2018, the PNM has 100,000+ registered members.[33][34]

Rise to power

When Eric Williams returned to Trinidad in 1948 he set about developing a political base. Between 1948 and 1955 he delivered a series of political lectures, under the auspices of the Political Education Movement (PEM) a branch of the Teachers Education and Cultural Association. Naparima College is one of the locations at which such lectures were delivered.[35] On 15 January 1956 Williams launched the PNM. In the 1956 General Elections the PNM captured 13 of the 24 elected seats in the Legislative Council with 38.7% of the votes cast. In order to secure an outright majority in the Legislative Council Williams managed to convince the Secretary of State for the Colonies to allow him to name the five appointed members of the council (despite the opposition of the Governor Sir Edward Betham Beetham).[36] This gave him a clear majority in the Legislative Council. Williams was thus elected Chief Minister and was also able to get all seven of his ministers elected.

In the 1958 Federal Elections (which the PNM contested as part of the West Indies Federal Labour Party), it won four of the 10 Trinidad and Tobago seats with 47.4% of the vote. The Opposition, Democratic Labour Party won the other six seats.[37]

Independence era

In the 1961 General Elections the PNM won 20 of 30 seats with 58% of the vote. With the collapse of the West Indian Federation, the PNM led Trinidad and Tobago to independence on 31 August 1962.

In the 1966 General Elections the PNM won 24 of 36 seats, with 52% of the vote. However, economic and social discontent grew under PNM rule. This came to a climax in April 1970 with the Black Power Revolution. On 13 April, PNM Deputy Leader and Minister of External Affairs A. N. R. Robinson resigned from the party and government. On 20 April, facing a revolt by a portion of the Army in collusion with the growing Black Power movement, Williams declared a State of Emergency.[38] By 22 April, the mutineers had begun negotiations for surrender. Following this certain ministers were forced to resign including John O'Halloran, Minister of Industry and Gerard Montano, Minister of Home Affairs.

In the 1971 General Elections the PNM faced only limited opposition as the major opposition parties boycotted the election citing the use of voting machines.[39] The PNM captured all 36 seats in the election, including eight that they carried unopposed. Additionally, Williams split the post of Deputy Leader into three and appointed Kamaluddin Mohammed, Errol Mahabir and George Chambers to the position.

In 1972, J. R. F. Richardson crossed the floor and declared himself an Independent.[40] He was subsequently appointed Leader of the Opposition. He was soon joined by another MP, Dr. Horace Charles.

In 1973, the PNM faced a major crisis. On 28 September Williams announced that he would not stand for re-election. This led to a race to succeed him as Political Leader of the party. By 18 November 250 of 476 registered party groups had submitted nominations, 224 of them for Attorney General Karl Hudson-Phillips and 26 for Minister of Health, Kamaluddin Mohammed. Williams announced on 2 December that he would return as Political Leader and Hudson-Phillips was forced out of the party.[41]

Decline and fall

In 1976 the PNM won 24 of 36 seats with 54% of the vote. In March 1978, Hector McClean, Minister of Works, resigned from the party and government and declared himself an independent MP.

On 29 March 1981, Eric Williams died. Williams had maintained an iron grip over the party and forced all potential rivals out of the party. In the absence of a clear successor, President Ellis Clarke was left to choose the new Prime Minister from among the three Deputy Political Leaders of the party. Clarke appointed George Chambers Prime Minister in preference to Kamaluddin Mohammed and Errol Mahabir.[42] Chambers was subsequently elected as Political Leader of the PNM and led the party to victory in the 1981 General Elections. The PNM won 26 of 36 seats and 52% of the vote.

It subsequently held on to power until 1986 when it was defeated by the National Alliance for Reconstruction (NAR) under the leadership of A. N. R. Robinson. The PNM won three of 36 seats, with 32% of the vote. Chambers resigned and was succeeded by Patrick Manning as Political Leader.[43]

Manning and the PNM re-invented

When Manning became leader he promised a "new PNM" and purposely ignored the discredited old guard. He appointed Wendell Mottley, Keith Rowley and Augustus Ramrekersingh as his deputy leaders.[44]

The PNM was returned to power in the 1991 elections after the NAR self-destructed. In the 1991 election it won 21 of 36 seats with 45% of the vote. However, in the latter half of that term the party became unstable. It lost one seat in a by-election and another when Ralph Maraj defected to the United National Congress. The issue that led Maraj to defect was the declaration of a limited State of Emergency which sole purpose was to remove Occah Seepaul (Maraj's sister) as Speaker of the House of Representatives.[45] The party also suffered a loss of support with the death Minister of Public Utilities, Morris Marshall, a favourite of the party grassroots. Attempting to halt the decline in party support Manning called an early "snap election" in 1995 . Many party front-benchers did not seek reelection including Finance Minister Wendell Mottley.

The party lost the 1995 General Elections winning 17 of 36 seats with 48% of the vote. The United National Congress (UNC) under the leadership of Basdeo Panday also won 17 seats and formed a coalition government with the National Alliance for Reconstruction which had won the remaining two seats. The PNM was further weakened when two MPs resigned from the party and threw their support behind the UNC government. This led to numerous calls for Manning to resign the party leadership, and for calls for Mottley to replace him. Manning declined to resign and Mottley appeared to have taken a sabbatical from politics. When leadership elections were held in 1997 Manning was challenged by Keith Rowley. Manning was returned as Political Leader.

In 2000 the PNM suffered another defeat, winning 16 of 36 seats with 46% of the vote. Another election was held in 2001 which resulted in a tie with both the PNM and UNC winning 18 seats, the PNM with 46% of the electoral vote and the UNC with 50%. However President Arthur N.R. Robinson appointed Manning as Prime Minister on the basis of "moral and spiritual grounds". (In Trinidad and Tobago's elections, the number of seats needed to occupy the lower house is really the best indicator of whether or not a party would win elections). Unable to elect a Speaker, Manning advised the President to prorogue Parliament. On 7 October 2002 General Elections were held in which the PNM won 50.7% of popular votes and 20 out of 36 seats.[46]

In government since 2015

On 9 September 2015, Keith Rowley was sworn in as the new Prime Minister, following the election victory of the PNM.[47] In August 2020, the governing PNM won the following general election, leading to the incumbent Prime Minister Keith Rowley serving a second term.[48]

Leaders of the People's National Movement

The political leaders of the People's National Movement have been as follows (any acting leaders indicated in italics):[49][50]

Key:

PNM

UNC

NAR

PM: Prime Minister

LO: Leader of the Opposition

†: Died in office

| Leader | Term of Office | Position | Prime Minister | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Eric Williams |

|

24 January 1956[51] | 29 March 1981† | PM 1955–1981 | himself | |

| 2 | George Chambers |

|

30 March 1981[52] | 8 February 1987 | PM 1981–1986 | himself | |

| 3 | Patrick Manning |

|

8 February 1987 | 27 May 2010 | LO 1986–1991 | Robinson | |

| PM 1991–1995 | himself | ||||||

| LO 1995–2001 | Panday | ||||||

| PM 2001–2010 | himself | ||||||

| 4 | Keith Rowley |

|

27 May 2010 | Incumbent | LO 2010–2015 | Persad-Bissessar | |

| PM 2015–2025 | himself | ||||||

Deputy leaders of the People's National Movement

The deputy political leaders of the People's National Movement have been as follows (any acting leaders indicated in italics):

| Deputy Leader | Term | Concurrent Office(s) | Deputy Leader | Term | Concurrent Office(s) | Deputy Leader | Term | Concurrent Office(s) | Deputy Leader | Term | Concurrent Office(s) | Leader(s) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patrick Solomon[53]

(1910-1997) MP for Port of Spain South |

|

1956 | 1966 |

|

Williams | ||||||||||||||||||||

| A. N. R. Robinson[54]

(1926-2014) MP for Tobago East |

|

1967 | 1970 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| George Chambers

(1928-1997) MP for St. Ann's East |

|

1971 | 30 March 1981 | Errol Mahabir

(1931-2015) MP for San Fernando West |

|

1971 | Kamaluddin Mohammed (1927-2015)MP for Barataria |

|

1971 | ||||||||||||||||

| Keith Rowley

(born 1949) MP for Diego Martin West |

|

1987 | 1995 | Wendell Mottley (born 1941) MP for St. Ann's East |

|

Augustus Ramrekersingh (born )MP for St. Joseph |

|

|

Manning | ||||||||||||||||

| Joan Yuille-Williams

(born ) (party and elections) |

|

1996[55] | 14 January 2023[56] |

|

Kenneth Valley

(1948-2011) MP for |

|

Nafeesa Mohammed (born ) |

|

1997 | 2011 |

|

Orville London (born 1945[57]) (Tobago) AM for Scarborough/Calder Hall |

|

1998[58] | 3 July 2016 | Chief Secretary of Tobago | |||||||||

| Rohan Sinanan

(born ) (policy (2010-2023) (party and election matters (2023-present) |

|

Incumbent |

|

Marlene McDonald

(born ) (legislation) MP for Port of Spain South |

|

13 August 2019 |

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Rowley | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Fitzgerald Hinds (born 1956[59]) (legislation) MP for Laventille West |

|

10 November 2019 | 14 January 2023[56] |

|

Kelvin Charles (born 1957[60]) (Tobago) AM for Black Rock/Whim/Spring Garden |

|

3 July 2016 | 26 January 2020 | Chief Secretary of Tobago | ||||||||||||||||

| Tracy Davidson-Celestine

(born 1978) (Tobago) |

|

26 January 2020 | 1 May 2022 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

Tobago Council leaders

The deputy political leaders who additionally served as the political leaders of the Tobago Council of the People's National Movement have been as follows (any acting leaders indicated in italics):

Key:

PNM

PDP

MaL: Majority Leader

MiL: Minority Leader

| Leader | Term | Position | Chief Secretary | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Orville London |

|

2001 | 3 July 2016 | MaL 2001–2017 | himself | |

| 2 | Kelvin Charles |

|

3 July 2016 | 26 January 2020 | MaL 2017–2020 | himself | |

| 3 | Tracy Davidson-Celestine |

|

26 January 2020

(Elected) |

1 May 2022 | None (lost the December 2021 Tobago House of Assembly election for her electoral district) |

Kelvin Charles | |

| Ancil Dennis | |||||||

| Farley Chavez Augustine | |||||||

| 4 | Ancil Dennis |

|

1 May 2022

(Elected) |

None (lost the December 2021 Tobago House of Assembly election for his electoral district) |

Farley Chavez Augustine | ||

PNM Leadership Executive Committee

| Position | Officeholder | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Political Leader | Keith Rowley | ||

| Chairman | Stuart Young | ||

| Lady Vice-Chairman | Camille Robinson-Regis | ||

| Vice-Chairman | Vacant | ||

| Deputy Political Leader | Legislative Matters | Colm Imbert | |

| Policy Matters | Nyan Gadsby-Dolly | ||

| Party and Election Matters | Rohan Sinanan | ||

| Tobago Council Political Leader | Ancil Dennis | ||

| General Secretary | Foster Cummings | ||

| Assistant General Secretary | Patricia Alexis | ||

| Treasurer | Kazim Hosein | ||

| Public Relations Officer | Faris Al-Rawi | ||

| Education Officer | Laurel Lezama Lee Sing | ||

| Labour Relations Officer | Jennifer Baptiste-Primus | ||

| Elections Officer | Indar Parasam | ||

| Field Officer | Terrence Beepath | ||

| Welfare Officer | Maxine Richards | ||

| Youth Officer | Jeniece Scott | ||

| Operations Officer | Irene Hinds | ||

| Social Media Officer | Kwasi Robinson | ||

Youth Arm

| Position | Officeholder | |

|---|---|---|

| Chairperson | Patrick Phillip | |

Women's Arm

| Position | Officeholder | |

|---|---|---|

| Chairwoman | Camille Robinson-Regis | |

Tobago Council of the People's National Movement

Tobago House of Assembly Seats | |

|---|---|

| Tobago House of Assembly | 1 / 15 |

Tobago has its own PNM party with separate memberships, constituency associations, executives, offices and a political leader.

| Party | Leader | Last election | Government | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Votes (%) | Seats | |||||

| Tobago Council of the PNM | Ancil Dennis |

|

2021 | 40.8 | 1 / 15 |

Progressive Democratic Patriots | |

Electoral history

House of Representatives

| Election | Party leader | Votes | Seats | Position | Government | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | ± | No. | ± | |||||

| 1956 | Eric Williams | 105,513 | 39.8% | — | 13 / 24 |

1st | PNM | ||

| 1961 | 190,003 | 57.0% | 20 / 30 |

PNM | |||||

| 1966 | 158,573 | 52.4% | 24 / 36 |

PNM | |||||

| 1971 | 99,723 | 84.1% | 36 / 36 |

PNM | |||||

| 1976 | 169,194 | 54.2% | 24 / 36 |

PNM | |||||

| 1981 | George Chambers | 218,557 | 52.9% | 26 / 36 |

PNM | ||||

| 1986 | 183,635 | 32.0% | 3 / 36 |

NAR | |||||

| 1991 | Patrick Manning | 233,150 | 45.1% | 21 / 36 |

PNM | ||||

| 1995 | 256,159 | 48.8% | 17 / 36 |

UNC–NAR | |||||

| 2000 | 276,334 | 46.5% | 16 / 36 |

UNC | |||||

| 2001 | 260,075 | 46.5% | 18 / 36 |

PNM Minority | |||||

| 2002 | 308,762 | 50.9% | 20 / 36 |

PNM | |||||

| 2007 | 299,813 | 45.85% | 26 / 41 |

PNM | |||||

| 2010 | 285,354 | 39.65% | 12 / 41 |

PP | |||||

| 2015 | Keith Rowley | 378,447 | 51.68% | 23 / 41 |

PNM | ||||

| 2020 | 322,250 | 49.08% | 22 / 41 |

PNM | |||||

| 2025 | |||||||||

West Indies

| Election | Party Group | Leader | Votes | Seats | Position | Government | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Share | No. | Share | ||||||||

| 1958[37] | WIFLP | Eric Williams | 119,527 | 47.4% | 4 / 10 |

40.0% | 2nd | WIFLP | |||

Corporations

| Election[61] | Votes | Councillors | Corporations | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leader | No. | Vote share | ± | No. | ± | No. | ± | ||

| 1959 | Eric Williams | 140,275 | 48.1% | — | 33 / 72 |

? | |||

| 1968 | ? | 49.4% | 68 / 100 |

? | |||||

| 1971 | 12,287 | 52.1% | 90 / 100 |

? | |||||

| 1977 | 64,725 | 51.1% | 68 / 100 |

? | |||||

| 1980 | 74,667 | 57.8% | 100 / 113 |

11 / 11 |

|||||

| 1983[62] | George Chambers | ? | 39.1% | 54 / 120 |

5 / 11 |

||||

| 1987[62] | Patrick Manning | ? | 39.3% | 46 / 125 |

3 / 11 |

||||

| 1992 | 154.818 | 50.3% | 86 / 139 |

10 / 14 |

|||||

| 1996 | 155,585 | 43.7% | 63 / 124 |

7 / 14 |

|||||

| 1999 | 157,631 | 46.6% | 67 / 124 |

7 / 14 |

|||||

| 2003 | 172,525 | 53.3% | 83 / 126 |

9 / 14 |

|||||

| 2010 | Keith Rowley | 130,505 | 33.6% | 36 / 134 |

5 / 14 |

||||

| 2013 | 190,421 | 42.3% | 84 / 136 |

8 / 14 |

|||||

| 2016 | 174,754 | 48.2% | 83 / 137 |

8 / 14 |

|||||

| 2019 | 161,962 | 43.5% | 72 / 139 |

7 / 14 |

|||||

| 2023 | 130,868 | 39.5% | 70 / 141 |

7 / 14 |

|||||

Tobago House of Assembly

| Election[63] | Leader | Votes | Seats | Position | Government | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | ± | No. | ± | |||||

| 1980 | Eric Williams

(National party leader) |

7,097 | 44.4 | — | 4 / 12 |

2nd | DAC | ||

| 1984 | George Chambers

(National party leader) |

8,200 | 41.4 | 1 / 12 |

DAC | ||||

| 1988 | Patrick Manning

(National party leader) |

5,977 | 35.8 | 1 / 12 |

DAC | ||||

| 1992 | 6,555 | 36.7 | 1 / 12 |

NAR | |||||

| 1996 | 5,023 | 33.6 | 1 / 12 |

NAR | |||||

| 2001 | Orville London | 10,500 | 46.7 | 8 / 12 |

PNM | ||||

| 2005 | 12,137 | 58.4 | 11 / 12 |

PNM | |||||

| 2009 | 12,311 | 51.2 | 8 / 12 |

PNM | |||||

| 2013 | 19,976 | 61.2 | 12 / 12 |

PNM | |||||

| 2017 | Kelvin Charles | 13,310 | 54.7 | 10 / 12 |

PNM | ||||

| January 2021 | Tracy Davidson-Celestine | 13,288 | 50.4 | 6 / 12 |

Caretaker | ||||

| December 2021 | 11,943* | 40.8* | 1 / 15 |

PDP | |||||

See also

- 2022 People's National Movement leadership election

- 2020 Tobago Council of the People's National Movement leadership election

References

- ^ Alexander, Gail. "Slightly better Sunday turnout for PNM election". Trinidad & Tobago Guardian.

- ^ Clyne, Kalifa Sarah (1 October 2018). "Red and Rowley takes early lead in PNM elections - Trinidad and Tobago Newsday". newsday.co.tt. Retrieved 17 September 2023.

- ^ "Caribbean Elections | People's National Movement". www.caribbeanelections.com. Archived from the original on 13 August 2020. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- ^ Encyclopedia of World Political Systems. Routledge. 2016. ISBN 978-1-317-47156-1. Archived from the original on 25 February 2022. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- ^ Wagg, Stephen (14 November 2017). Cricket: A Political History of the Global Game, 1945-2017: 1945 to 2012. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-55729-6. Archived from the original on 18 April 2021. Retrieved 31 December 2020.

- ^ "BTI 2020 Trinidad and Tobago Country Report". BTI Blog. Archived from the original on 23 January 2021. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- ^ Gilmore, John T.; Allen, Beryl; McCallum, Dian; Ramdeen, Romila; Kerr, Ricardo (26 August 2019). Hodder Education Caribbean History: Freedom and Change. Hodder Education. ISBN 978-1-5104-3689-3. Archived from the original on 18 April 2021. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- ^ Lowenthal, David; Comitas, Lambros, eds. (1973). The Aftermath of Sovereignty: West Indian Perspectives (PDF). Anchor Books. p. 134. ISBN 978-0385043045. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- ^ Griffith, Ivelaw L. (1993). The quest for security in the Caribbean : problems and promises in subordinate states. M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 978-1-56324-089-8. Archived from the original on 18 April 2021. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ "Caribbean Elections | People's National Movement". www.caribbeanelections.com. Archived from the original on 13 August 2020. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- ^ Lowenthal, David; Comitas, Lambros, eds. (1973). The Aftermath of Sovereignty: West Indian Perspectives (PDF). Anchor Books. p. 134. ISBN 978-0385043045. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- ^ Griffith, Ivelaw L. (1993). The quest for security in the Caribbean : problems and promises in subordinate states. M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 978-1-56324-089-8. Archived from the original on 18 April 2021. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ Encyclopedia of world political systems. Sharpe Reference. 15 April 2016. ISBN 978-1-317-47156-1. Archived from the original on 18 April 2021. Retrieved 15 January 2020.

- ^ Derbyshire, J. Denis; Derbyshire, Ian (2016). Encyclopedia of World Political Systems. Routledge. p. 322. ISBN 9781317471561. Archived from the original on 18 April 2021. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- ^ Encyclopedia of world political systems. Sharpe Reference. 15 April 2016. ISBN 978-1-317-47156-1. Archived from the original on 18 April 2021. Retrieved 15 January 2020.

- ^

- "Let's do this: Everyone else who has used Labour's new slogan". Stuff. Archived from the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 15 January 2020.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Guardian Group. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 15 January 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "Economic Outline of Trinidad and Tobago - Bank of Scotland International Trade Portal". www.bankofscotlandtrade.co.uk. Archived from the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- "Trinidad and Tobago / Wirtschaftsanalysen - Coface". www.coface.at. Archived from the original on 1 December 2020. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- Skard, Torild (2015). Women of Power: Half a Century of Female Presidents and Prime Ministers Worldwide. Policy Press. p. 272. ISBN 978-1-4473-1580-3. Archived from the original on 18 April 2021. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- "Let's do this: Everyone else who has used Labour's new slogan". Stuff. Archived from the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 15 January 2020.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Guardian Group. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 15 January 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "Restricted access". Archived from the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- "Economic Outline of Trinidad and Tobago - Bank of Scotland International Trade Portal". www.bankofscotlandtrade.co.uk. Archived from the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- "Trinidad and Tobago / Wirtschaftsanalysen - Coface". www.coface.at. Archived from the original on 1 December 2020. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- Skard, Torild (2015). Women of Power: Half a Century of Female Presidents and Prime Ministers Worldwide. Policy Press. p. 272. ISBN 978-1-4473-1580-3. Archived from the original on 18 April 2021. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- ^ Trevett, Claire (4 August 2017). "Labour leader Jacinda Ardern not the only one wanting to 'do this'". NZ Herald. Archived from the original on 2 October 2019. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ "The Formative Years of the PNM". 4 December 2019. Archived from the original on 23 October 2020. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- ^ Hall, Kenneth (1 October 2012). Caribbean Integration from Crisis to Transformation and Repositioning. Trafford Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4669-4404-6. Archived from the original on 18 April 2021. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- ^ a b Gowricharn, Ruben (17 September 2020). Political Integration in Indian Diaspora Societies. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-000-18041-1.

- ^ a b Roopnarine, Urvashi Tiwari. "Politics and religion in San Fernando West". www.guardian.co.tt. Retrieved 8 July 2021.

- ^ Ramcharitar, Raymond (2021). A History of Creole Trinidad, 1956-2010. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-75634-5. ISBN 978-3-030-75633-8. S2CID 250255721.

- ^ "The legacy of Indian migration to European colonies". The Economist. 2 September 2017. Archived from the original on 1 September 2017. Retrieved 2 September 2017.

- ^ Payne, Anthony; Sutton, Paul (4 February 2014). Size and Survival: The Politics of Security in the Caribbean and the Pacific. Routledge. ISBN 9781135236816. Archived from the original on 18 April 2021. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- ^ Birdsall, Nancy; Deosaran, Ramesh; Tincani, Amos; Suárez, Elena M.; Bloomfield, Richard J.; Rajapatirana, Sarath; Serbin, Andrés; Henrikson, Alan K.; Skeete, Charles A. T.; Ross-Brewster, Havelock R. H.; Walch, Karen S.; Bloomfield, Steven B.; Meins, Bertus J. (January 1996). Choices and Change: Reflections on the Caribbean. Inter-American Development Bank. ISBN 9781886938076. Archived from the original on 7 July 2021. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- ^ "Ruling party holds its ground in local elections". country.eiu.com. Archived from the original on 18 April 2021. Retrieved 5 April 2021.

- ^ Premdas, Ralph (April 1996). "Ethnicity and Elections in The Caribbean: A Radical Realignment of Power in Trinidad and the Threat of Communal Strife" (PDF).

- ^ Horowitz, Donald L. "Ethnic Groups in Conflict. Chapter 7.

- ^ "PNM - The People's National Movement". www.facebook.com. Archived from the original on 7 July 2021. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- ^ "Senate passes marriage bill; Opposition abstains". www.looptt.com. Archived from the original on 30 October 2020. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- ^ "The new government of Trinidad and Tobago is set to roll out a new national insurance system". Oxford Business Group. 12 July 2016. Archived from the original on 25 January 2021. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

- ^ "Caribbean Elections | People's National Movement". www.caribbeanelections.com. Archived from the original on 13 August 2020. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

- ^ "PNM ready, not the UNC, for by-elections". Trinidad and Tobago Newsday. 11 June 2018. Archived from the original on 27 January 2021. Retrieved 18 January 2021.

- ^ "PNM's .1M members ready for polls battle". Trinidad and Tobago Newsday. 19 September 2018. Archived from the original on 27 January 2021. Retrieved 18 January 2021.

- ^ Pierre, Maurice St (5 March 2015). Eric Williams and the Anticolonial Tradition: The Making of a Diasporan Intellectual. University of Virginia Press. ISBN 978-0-8139-3685-7. Archived from the original on 18 April 2021. Retrieved 5 April 2021.

- ^ Alleyne, George (21 October 2009). "A leader can be challenged". Trinidad and Tobago News Blog. Archived from the original on 2 December 2020. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- ^ a b "Report on the Election of Members to the Federal House of Representatives from the Territory of T&T 1958 (25th March 1958) | Elections And Boundaries Commission". Archived from the original on 29 September 2020. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- ^ "Black Power: State of Emergency Remembered". www.guardian.co.tt. Archived from the original on 4 November 2019. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- ^ "Trinidad and Tobago General Election Results 1971". www.caribbeanelections.com. Archived from the original on 11 August 2020. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- ^ "Caribbean Elections Biography | John R.F. Richardson". www.caribbeanelections.com. Archived from the original on 18 April 2021. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- ^ "TriniView.com - NewsPro Archive". www.triniview.com. Archived from the original on 20 August 2008. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- ^ "Remembering Kamal". Trinidad and Tobago Newsday. 15 December 2019. Archived from the original on 8 April 2020. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- ^ Hunte, Camille (4 August 2020). "Who will lead us out of the pandemic?". Trinidad Express Newspapers. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- ^ Ramnarine, Kevin. "The Manning legacy in energy". www.guardian.co.tt. Archived from the original on 18 April 2021. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- ^ "World News Briefs; Trinidad House Speaker Put Under House Arrest". The New York Times. Reuters. 5 August 1995. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 21 September 2020. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- ^ Shah, Raffique (22 March 2015). "Buying cat in bag". Trinidad and Tobago News Blog. Archived from the original on 23 January 2016. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- ^ Hutchinson-Jafar, Linda (9 September 2015). "Trinidad's new prime minister, Keith Rowley, sworn in". Reuters.

- ^ "Trinidad and Tobago poll: Governing party claims victory". BBC News. 11 August 2020.

- ^ "Party Leadership | People's National Movement". pnmtt.live. Archived from the original on 25 January 2021. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- ^ "History | People's National Movement". pnmtt.live. 4 December 2019. Archived from the original on 19 October 2020. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- ^ Ghany, Hamid. "AN ABSENCE OF FANFARE". www.guardian.co.tt. Retrieved 17 September 2023.

- ^ Alexander, Gail. "People's National Movement George Michael Chambers (1928-1997)". People's National Movement Trinidad and Tobago. Trinidad Guardian. Archived from the original on 27 June 2019. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- ^ "Flattering to Deceive | Trinidad and Tobago News Blog". 13 May 2010. Archived from the original on 12 March 2019. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- ^ "Index Ro-Ry". www.rulers.org. Archived from the original on 24 January 2020. Retrieved 20 January 2020.

- ^ Boodram, Annan (6 December 2012). "Women Power In T & T's Politics". Archived from the original on 27 January 2020. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- ^ a b "Gadsby-Dolly plans to reach out to party, public - CNC3". 18 January 2023. Retrieved 5 January 2025.

- ^ "Trinidad and Tobago Parliament". www.ttparliament.org. Archived from the original on 12 January 2020. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- ^ "His Excellency Orville London, High Commissioner for the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago". University of Oxford. Archived from the original on 25 July 2020. Retrieved 12 July 2020.

- ^ "The Former Minister of Public Utilities, Fitzgerald Ethelbert Hinds". The Ministry of Public Utilities. Retrieved 5 January 2025.

- ^ "Kelvin V. Charles". www.facebook.com. Archived from the original on 18 April 2021. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- ^ "Publications and Reports | Elections And Boundaries Commission". Archived from the original on 2 May 2020. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- ^ a b "Trinidad and Tobago - Political Dynamics". countrystudies.us. Archived from the original on 3 November 2016. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- ^ "Publications and Reports | Elections And Boundaries Commission". Archived from the original on 23 December 2019. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

External links

- Official website

- PNM Website (archived)

- Vision PNM (archived)

- PNM Abroad (archived)