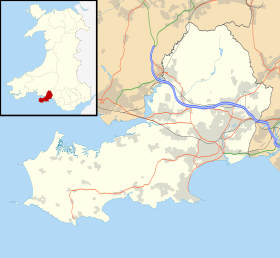

Pennard Castle

| Pennard Castle | |

|---|---|

| Gower Peninsula, Wales | |

Exterior of the gatehouse | |

| Coordinates | 51°34′36″N 4°06′08″W / 51.5766°N 4.1023°W |

| Type | Ringwork |

| Site information | |

| Controlled by | Pennard Golf Course |

| Open to the public | Yes |

| Condition | Ruined |

| Site history | |

| Materials | Stone |

Pennard Castle is a ruined castle, near the modern village of Pennard on the Gower Peninsula, in south Wales. The castle was built in the early 12th century as a timber ringwork following the Norman invasion of Wales. The walls were rebuilt in stone by the Braose family at the turn of the 13th and 14th centuries, including a stone gatehouse. Soon afterwards, however, encroaching sand dunes caused the site to be abandoned and it fell into ruin. Restoration work was carried out during the course of the 20th century and the remains of the castle are now protected under UK law as a Grade II* listed building.

History

13th-14th centuries

The Normans began to make incursions into South Wales from the late-1060s onwards, pushing westwards from their bases in recently occupied England.[1] Their advance was marked by the construction of castles and the creation of regional lordships.[2] Pennard Castle was built at the start of the 12th century after Henry de Beaumont, the Earl of Warwick, conquered the Gower Peninsula and made Pennard one of his demesne manors.[3]

The castle was constructed on a limestone spur, overlooking the mouth of the Pennard Pill stream and Three Cliffs Bay, and was protected to the north and west by surrounding cliffs.[4] The fortification initially took the form of an oval-shaped ringwork, 34 by 28 metres (112 by 92 ft), with a defensive ditch and ramparts around the outside, and a timber hall in the centre.[5] A local church, St Mary's, was built just to the east and a settlement grew up around the site; a rabbit warren was established in the nearby sand dunes.[6] In the early 13th century, a simple stone hall, approximately 18.6 by 7.6 metres (61 by 25 ft), was built on the site of the older timber building, using red-purple sandstone with white limestone detailing.[7]

Around the turn of the 13th and 14th centuries, while the castle was controlled by William and his son, also called William, the timber defences were replaced.[8] A thin stone curtain wall, approximately 8 metres (26 ft) tall with battlements, replaced the palisades, with the mural defences including a square tower on a rocky spur on the west side, and a circular tower on the north-west corner.[9] A gatehouse was built as the new entrance, with two half-circular towers that possibly imitated those of regional castles such as Caerphilly; it was weakly defended by a portcullis and a handful of arrow loops.[10] The new walls were built from a mixture of red sandstone rubble, probably quarried locally, and limestone dug from the castle site itself.[11] The Braoses may have rebuilt Pennard as a replacement for their castle at nearby Penmaen which was abandoned at around the same time due to encroaching sand dunes.[12]

16th-21st centuries

Pennard Castle also began to suffer from sand dune encroachment and the castle and its settlement were gradually abandoned.[13][nb 1] A survey in 1650 described the fortification as being "desolate and ruinous" and surrounded by sand.[13] By 1741, the castle's south wall had mostly collapsed but the remainder of the castle was apparently still generally intact, although it had suffered further losses by 1795.[15] It was a popular subject for engravings, sketches and paintings from the 18th century onwards, with the view of the ruins from the east proving particularly popular.[14] By 1879, large cracks had appeared in the southern tower of the gatehouse, which led to its partial collapse.[16]

By 1922, concerns had grown about the condition of the castle and discussions took place between the Pennard Golf Club, who owned the site, the Royal Institution and the Cambrian Archaeological Association.[17] A joint committee was formed to raise the funds for repairs to the stonework but the costs appear to have been excessive and instead the gatehouse was patched with concrete between 1923 and 1924.[18] Much of the remaining southern wall collapsed at the beginning of 1960 and an archaeological survey was conducted between 1960 and 1961.[19] Urgent masonry repairs were then carried out in 1963, paid for by a combination of the Ministry of Public Building and Works, the Gower Society, the golf club and a public appeal launched by local newspapers.[20]

In the 21st century, the ruins of the gatehouse still survive, reaching up to the battlements on its east side, partially because it was built with very strong mortar.[21] Parts of the curtain wall survive, mainly on the north and east sides, now around 1.1 metres (3 ft 7 in) thick and averaging 5 metres (16 ft) tall, along with the remains of the square mural tower.[22] The ruins are protected under UK law as a grade II* listed building and a scheduled ancient monument.[23]

See also

Notes

References

- ^ Carpenter 2004, p. 110

- ^ Prior 2006, p. 141; Carpenter 2004, p. 110

- ^ Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales 1991, p. 288

- ^ Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales 1991, pp. 289, 291; "Historic Wales Report", Historic Wales, retrieved 30 April 2016

- ^ Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales 1991, pp. 289–290

- ^ Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales 1991, pp. 288–289

- ^ Alcock 1960, p. 67; Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales 1991, p. 290

- ^ Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales 1991, pp. 288–289, 292

- ^ Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales 1991, pp. 288–289, 292, 295

- ^ Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales 1991, pp. 293, 295; "Historic Wales Report", Historic Wales, retrieved 30 April 2016

- ^ Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales 1991, p. 293; "Historic Wales Report", Historic Wales, retrieved 30 April 2016

- ^ Alcock 1960, pp. 69–70; Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales 1991, p. 289

- ^ a b Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales 1991, p. 289

- ^ a b Morris 1987, p. 8

- ^ Morris 1987, p. 6

- ^ Morris 1987, p. 10

- ^ Morris 1987, pp. 10–12

- ^ Morris 1987, pp. 10–13

- ^ Alcock 1961, pp. 79–80

- ^ Morris 1987, pp. 13–14

- ^ Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales 1991, pp. 292, 295

- ^ Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales 1991, pp. 291–292

- ^ "Pennard Castle", www.britishlistedbuildings.co.uk., British Listed Buildings, retrieved 29 April 2016

Bibliography

- Alcock, Leslie (1960). "Recent Archaeological Excavation and Discovery in Glamorgan". Morgannwg: Transactions of the Glamorgan Local History Society. 4: 67–70.

- Alcock, Leslie (1961). "Recent Archaeological Excavation and Discovery in Glamorgan". Morgannwg: Transactions of the Glamorgan Local History Society. 5: 79–82.

- Carpenter, David (2004). The Struggle for Mastery: The Penguin History of Britain 1066–1284. London, UK: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-014824-4.

- Morris, Bernard (1987). "Pennard Castle". Gower. 38: 6–15.

- Prior, Stuart (2006). A Few Well-Positioned Castles: The Norman Art of War. Stroud, UK: Tempus. ISBN 9780752436517.

- Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales (1991). An Inventory of the Ancient Monuments in Glamorgan: Volume III: Medieval Secular Monuments, the Early Castles from the Norman Conquest to 1217. London, UK: HMSO. ISBN 9780113000357.