Pelagianism

| Pelagianism |

|---|

| History |

| Proponents |

| Opponents |

| Doctrines |

|

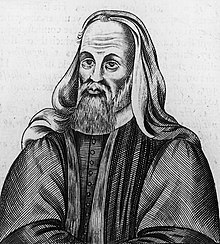

Pelagianism is a Christian theological position that holds that the fall did not taint human nature and that humans by divine grace have free will to achieve human perfection. Pelagius (c. 355 – c. 420 AD), an ascetic and philosopher from the British Isles, taught that God could not command believers to do the impossible, and therefore it must be possible to satisfy all divine commandments. He also taught that it was unjust to punish one person for the sins of another; therefore, infants are born blameless. Pelagius accepted no excuse for sinful behaviour and taught that all Christians, regardless of their station in life, should live unimpeachable, sinless lives.

To a large degree, "Pelagianism" was defined by its opponent Augustine, and exact definitions remain elusive. Although Pelagianism had considerable support in the contemporary Christian world, especially among the Roman elite and monks, it was attacked by Augustine and his supporters, who had opposing views on grace, predestination and free will. Augustine proved victorious in the Pelagian controversy; Pelagianism was decisively condemned at the 418 Council of Carthage and is regarded as heretical by the Roman Catholic Church and Eastern Orthodox Church. For centuries afterward, "Pelagianism" was used in various forms as an accusation of heresy for Christians who hold unorthodox beliefs, but some recent scholarship has offered a different opinion.

Background

During the fourth and fifth centuries, the Church was experiencing rapid change due to the Constantinian shift to Christianity.[1] Many Romans were converting to Christianity, but they did not necessarily follow the faith strictly.[2] As Christians were no longer persecuted, they faced a new problem: how to avoid backsliding and nominal adherence to the state religion while retaining the sense of urgency originally caused by persecution. For many, the solution was adopting Christian asceticism.[1]

Early Christianity was theologically diverse. While Western Christianity taught that death was the result of the fall of man, a Syrian tradition including the second-century figures Theophilus and Irenaeus asserted that mortality preceded the fall. Around 400, the doctrine of original sin was just emerging in Western Christianity, deriving from the teaching of Cyprian that infants should be baptized for the sin of Adam. Other Christians followed Origen in the belief that infants are born in sin due to their failings in a previous life. Rufinus the Syrian, who came to Rome in 399 as a delegate for Jerome, followed the Syrian tradition, declaring that man had been created mortal and that each human is only punished for his own sin.[3]

Pelagius (c. 355–c. 420)[4] was an ascetic layman, probably from the British Isles, who moved to Rome in the early 380s.[5][6] Like Jerome, Pelagius criticized what he saw as an increasing laxity among Christians, instead promoting higher moral standards and asceticism.[4][7][6] He opposed Manicheanism because of its fatalism and determinism[1] and argued for the possibility of a sinless life.[8] Although Pelagius preached the renunciation of earthly wealth,[9] his ideas became popular among parts of the Roman elite.[5][7][1] Historian Peter Brown argued that Pelagianism appealed "to a powerful centrifugal tendency in the aristocracy of Rome—a tendency to scatter, to form a pattern of little groups, each striving to be an elite, each anxious to rise above their neighbours and rivals—the average upper‐class residents of Rome."[10] The powerful Roman administrator Paulinus of Nola was close to Pelagius and the Pelagian writer Julian of Eclanum,[11] and the former Roman aristocrat Caelestius was described by Gerald Bonner as "the real apostle of the so-called Pelagian movement".[8] Many of the ideas Pelagius promoted were mainstream in contemporary Christianity, advocated by such figures as John Chrysostom, Athanasius of Alexandria, Jerome, and even the early Augustine.[12][13]

Pelagian controversy

In 410, Pelagius and Caelestius fled Rome for Sicily and then North Africa due to the Sack of Rome by Visigoths.[8][14] At the 411 Council of Carthage, Caelestius approached the bishop Aurelius for ordination, but instead he was condemned for his belief on sin and original sin.[15][16][a] Caelestius defended himself by arguing that this original sin was still being debated and his beliefs were orthodox. His views on grace were not mentioned, although Augustine (who had not been present) later claimed that Caelestius had been condemned because of "arguments against the grace of Christ."[17] Unlike Caelestius, Pelagius refused to answer the question as to whether man had been created mortal, and, outside of Northern Africa, it was Caelestius' teachings which were the main targets of condemnation.[15] In 412, Augustine read Pelagius' Commentary on Romans and described its author as a "highly advanced Christian."[18] Augustine maintained friendly relations with Pelagius until the next year, initially only condemning Caelestius' teachings, and considering his dispute with Pelagius to be an academic one.[8][19]

Jerome attacked Pelagianism for saying that humans had the potential to be sinless, and connected it with other recognized heresies, including Origenism, Jovinianism, Manichaeanism, and Priscillianism. Scholar Michael Rackett noted that the linkage of Pelagianism and Origenism was "dubious" but influential.[20] Jerome also disagreed with Pelagius' strong view of free will. In 415, he wrote Dialogus adversus Pelagianos to refute Pelagian statements.[21] Noting that Jerome was also an ascetic and critical of earthly wealth, historian Wolf Liebeschuetz suggested that his motive for opposing Pelagianism was envy of Pelagius' success.[22] In 415, Augustine's emissary Orosius brought charges against Pelagius at a council in Jerusalem, which were referred to Rome for judgement.[19][23] The same year, the exiled Gallic bishops Heros of Arles and Lazarus of Aix accused Pelagius of heresy, citing passages in Caelestius' Liber de 13 capitula.[8][24] Pelagius defended himself by disavowing Caelestius' teachings, leading to his acquittal at the Synod of Diospolis in Lod, which proved to be a key turning point in the controversy.[8][25][26] Following the verdict, Augustine convinced two synods in North Africa to condemn Pelagianism, whose findings were partially confirmed by Pope Innocent I.[8][19] In January 417, shortly before his death, Innocent excommunicated Pelagius and two of his followers. Innocent's successor, Zosimus, reversed the judgement against Pelagius, but backtracked following pressure from the African bishops.[8][25][19] Pelagianism was later condemned at the Council of Carthage in 418, after which Zosimus issued the Epistola tractoria excommunicating both Pelagius and Caelestius.[8][27] Concern that Pelagianism undermined the role of the clergy and episcopacy was specifically cited in the judgement.[28]

At the time, Pelagius' teachings had considerable support among Christians, especially other ascetics.[29] Considerable parts of the Christian world had never heard of Augustine's doctrine of original sin.[27] Eighteen Italian bishops, including Julian of Eclanum, protested against the condemnation of Pelagius and refused to follow Zosimus' Epistola tractoria.[30][27] Many of them later had to seek shelter with the Greek bishops Theodore of Mopsuestia and Nestorius, leading to accusations that Pelagian errors lay beneath the Nestorian controversy over Christology.[31] Both Pelagianism and Nestorianism were condemned at the Council of Ephesus in 431.[32][31] With its supporters either condemned or forced to move to the East, Pelagianism ceased to be a viable doctrine in the Latin West.[30] Despite repeated attempts to suppress Pelagianism and similar teachings, some followers were still active in the Ostrogothic Kingdom (493–553), most notably in Picenum and Dalmatia during the rule of Theoderic the Great.[33] Pelagianism was also reported to be popular in Britain, as Germanus of Auxerre made at least one visit (in 429) to denounce the heresy. Some scholars, including Nowell Myres and John Morris, have suggested that Pelagianism in Britain was understood as an attack on Roman decadence and corruption, but this idea has not gained general acceptance.[8][34]

Pelagius' teachings

Free will and original sin

The idea that God had created anything or anyone who was evil by nature struck Pelagius as Manichean.[35] Pelagius taught that humans were free of the burden of original sin, because it would be unjust for any person to be blamed for another's actions.[29] According to Pelagianism, humans were created in the image of God and had been granted conscience and reason to determine right from wrong, and the ability to carry out correct actions.[36] If "sin" could not be avoided it could not be considered sin.[35][24] In Pelagius' view, the doctrine of original sin placed too little emphasis on the human capacity for self-improvement, leading either to despair or to reliance on forgiveness without responsibility.[37] He also argued that many young Christians were comforted with false security about their salvation leading them to relax their Christian practice.[38]

Pelagius believed that Adam's transgression had caused humans to become mortal, and given them a bad example, but not corrupted their nature,[39] while Caelestius went even further, arguing that Adam had been created mortal.[40] He did not even accept the idea that original sin had instilled fear of death among humans, as Augustine said. Instead, Pelagius taught that the fear of death could be overcome by devout Christians, and that death could be a release from toil rather than a punishment.[41] Both Pelagius and Caelestius reasoned that it would be unreasonable for God to command the impossible,[37][24] and therefore each human retained absolute freedom of action and full responsibility for all actions.[29][36][b] Pelagius did not accept any limitation on free will, including necessity, compulsion, or limitations of nature. He believed that teaching a strong position on free will was the best motivation for individuals to reform their conduct.[36]

Sin and virtue

He is a Christian

- who shows compassion to all,

- who is not at all provoked by wrong done to him,

- who does not allow the poor to be oppressed in his presence,

- who helps the wretched,

- who succors the needy,

- who mourns with the mourners,

- who feels another's pain as if it were his own,

- who is moved to tears by the tears of others,

- whose house is common to all,

- whose door is closed to no one,

- whose table no poor man does not know,

- whose food is offered to all,

- whose goodness all know and at whose hands no one experiences injury,

- who serves God all day and night,

- who ponders and meditates upon his commandments unceasingly,

- who is made poor in the eyes of the world so that he may become rich before God.

In the Pelagian view, by corollary, sin was not an inevitable result of fallen human nature, but instead came about by free choice[44] and bad habits; through repeated sinning, a person could corrupt their own nature and enslave themself to sin. Pelagius believed that God had given man the Old Testament and Mosaic Law in order to counter these ingrained bad habits, and when that wore off over time God revealed the New Testament.[35] However, because Pelagius considered a person to always have the ability to choose the right action in each circumstance, it was therefore theoretically possible (though rare) to live a sinless life.[29][45][36] Jesus Christ, held in Christian doctrine to have lived a life without sin, was the ultimate example for Pelagians seeking perfection in their own lives, but there were also other humans who were without sin—including some notable pagans and especially the Hebrew prophets.[35][46][d] This view was at odds with that of Augustine and orthodox Christianity, which taught that Jesus was the only man free of sin.[47] Pelagius did teach Jesus' vicarious atonement for the sins of mankind and the cleansing effect of baptism, but placed less emphasis on these aspects.[35]

Pelagius taught that a human's ability to act correctly was a gift of God,[45] as well as divine revelation and the example and teachings of Jesus. Further spiritual development, including faith in Christianity, was up to individual choice, not divine benevolence.[29][48] Pelagius accepted no excuse for sin, and argued that Christians should be like the church described in Ephesians 5:27, "without spot or wrinkle".[38][45][49][50] Instead of accepting the inherent imperfection of man, or arguing that the highest moral standards could only be applied to an elite, Pelagius taught that all Christians should strive for perfection. Like Jovinian, Pelagius taught that married life was not inferior to monasticism, but with the twist that all Christians regardless of life situation were called to a kind of asceticism.[1] Pelagius taught that it was not sufficient for a person to call themselves a Christian and follow the commandments of scripture; it was also essential to actively do good works and cultivate virtue, setting themselves apart from the masses who were "Christian in name only", and that Christians ought to be extraordinary and irreproachable in conduct.[38] Specifically, he emphasized the importance of reading scripture, following religious commandments, charity, and taking responsibility for one's actions, and maintaining modesty and moderation.[36][e] Pelagius taught that true virtue was not reflected externally in social status, but was an internal spiritual state.[36] He explicitly called on wealthy Christians to share their fortunes with the poor. (Augustine criticized Pelagius' call for wealth redistribution.)[9]

Baptism and judgment

Because sin in the Pelagian view was deliberate, with people responsible only for their own actions, infants were considered without fault in Pelagianism, and unbaptized infants were not thought to be sent to hell.[51] Like early Augustine, Pelagians believed that infants would be sent to purgatory.[52] Although Pelagius rejected that infant baptism was necessary to cleanse original sin, he nevertheless supported the practice because he felt it improved their spirituality through a closer union with Jesus.[53] For adults, baptism was essential because it was the mechanism for obtaining forgiveness of the sins that a person had personally committed and a new beginning in their relationship with God.[35][45] After death, adults would be judged by their acts and omissions and consigned to everlasting fire if they had failed: "not because of the evils they have done, but for their failures to do good".[38] He did not accept purgatory as a possible destination for adults.[19] Although Pelagius taught that the path of righteousness was open to all, in practice only a few would manage to follow it and be saved. Like many medieval theologians, Pelagius believed that instilling in Christians the fear of hell was often necessary to convince them to follow their religion where internal motivation was absent or insufficient.[38]

Comparison

Significant influences on Pelagius included Eastern Christianity, which had a more positive view of human nature,[37][54][53] and classical philosophy, from which he drew the ideas of personal autonomy and self-improvement.[1] After having previously credited Cicero's lost Hortensius for his eventual conversion to Christianity,[55] Augustine accused Pelagius' idea of virtue of being "Ciceronian", taking issue with the ideology of the dialogue's author as having overemphasized the role of human intellect and will.[56][f] Although his teachings on original sin were novel, Pelagius' views on grace, free will and predestination were similar to those of contemporary Greek-speaking theologians such as Origen, John Chrysostom, and Jerome.[53]

Theologian Carol Harrison commented that Pelagianism is "a radically different alternative to Western understandings of the human person, human responsibility and freedom, ethics and the nature of salvation" which might have come about if Augustine had not been victorious in the Pelagian controversy.[1] According to Harrison, "Pelagianism represents an attempt to safeguard God's justice, to preserve the integrity of human nature as created by God, and of human beings' obligation, responsibility and ability to attain a life of perfect righteousness."[58] However, this is at the expense of downplaying human frailty and presenting "the operation of divine grace as being merely external".[58] According to scholar Rebecca Weaver, "what most distinguished Pelagius was his conviction of an unrestricted freedom of choice, given by God and immune to alteration by sin or circumstance."[59]

Definition

What Augustine called "Pelagianism" was more his own invention than that of Pelagius.[40][60] According to Thomas Scheck, Pelagianism is the heresy of denying Catholic Church teaching on original sin, or more specifically the beliefs condemned as heretical in 417 and 418.[61][g] In her study, Ali Bonner (a lecturer at the University of Cambridge) found that there was no one individual who held all the doctrines of "Pelagianism", nor was there a coherent Pelagian movement,[60] although these findings are disputed.[62][63] Bonner argued that the two core ideas promoted by Pelagius were "the goodness of human nature and effective free will" although both were advocated by other Christian authors from the 360s. Because Pelagius did not invent these ideas, she recommended attributing them to the ascetic movement rather than using the word "Pelagian".[60] Later Christians used "Pelagianism" as an insult for theologically orthodox Christians who held positions that they disagreed with. Historian Eric Nelson defined genuine Pelagianism as rejection of original sin or denial of original sin's effect on man's ability to avoid sin.[64] Even in recent scholarly literature, the term "Pelagianism" is not clearly or consistently defined.[65]

Pelagianism and Augustinianism

Pelagius' teachings on human nature, divine grace, and sin were opposed to those of Augustine, who declared Pelagius "the enemy of the grace of God".[29][18][h] Augustine distilled what he called Pelagianism into three heretical tenets: "to think that God redeems according to some scale of human merit; to imagine that some human beings are actually capable of a sinless life; to suppose that the descendants of the first human beings to sin are themselves born innocent".[30][i] In Augustine's writings, Pelagius is a symbol of humanism who excluded God from human salvation.[18] Pelagianism shaped Augustine's ideas in opposition to his own on free will, grace, and original sin,[68][69][70] and much of The City of God is devoted to countering Pelagian arguments.[47] Another major difference in the two thinkers was that Pelagius emphasized obedience to God for fear of hell, which Augustine considered servile. In contrast, Augustine argued that Christians should be motivated by the delight and blessings of the Holy Spirit and believed that it was treason "to do the right deed for the wrong reason".[38] According to Augustine, credit for all virtue and good works is due to God alone,[71] and to say otherwise caused arrogance, which is the foundation of sin.[72]

According to Peter Brown, "For a sensitive man of the fifth century, Manichaeism, Pelagianism, and the views of Augustine were not as widely separated as we would now see them: they would have appeared to him as points along the great circle of problems raised by the Christian religion".[73] John Cassian argued for a middle way between Pelagianism and Augustinianism, in which the human will is not negated but presented as intermittent, sick, and weak,[58] and Jerome held a middle position on sinlessness.[74] In Gaul, the so-called "semi-Pelagians" disagreed with Augustine on predestination (but recognized the three Pelagian doctrines as heretical) and were accused by Augustine of being seduced by Pelagian ideas.[75] According to Ali Bonner, the crusade against Pelagianism and other heresies narrowed the range of acceptable opinions and reduced the intellectual freedom of classical Rome.[76] When it came to grace and especially predestination, it was Augustine's ideas, not Pelagius', which were novel.[77][78][79]

| Belief | Pelagianism | Augustinianism |

|---|---|---|

| Fall of man | Sets a bad example, but does not affect human nature[44][35] | Every human's nature is corrupted by original sin, and they also inherit moral guilt[44][35] |

| Free will | Absolute freedom of choice[29][36] | Original sin renders men unable to choose good[80] |

| Status of infants | Blameless[51] | Corrupted by original sin and consigned to hell if unbaptized[81][44][35] |

| Sin | Comes about by free choice[44] | Inevitable result of fallen human nature[44] |

| Forgiveness for sin | Given to those who sincerely repent and merit it[j] | Part of God's grace, disbursed according to His will[82] |

| Sinlessness | Theoretically possible, although unusual[29][48] | Impossible due to the corruption of human nature[81] |

| Salvation | Humans will be judged for their choices[29] | Salvation is bestowed by God's grace[83] |

| Predestination | Rejected[84] | God decides who is saved and prevents them from falling away.[85] Though the explicit teaching of double predestination by Augustine is debated,[86][87] it is at least implied.[88] |

According to Nelson, Pelagianism is a solution to the problem of evil that invokes libertarian free will as both the cause of human suffering and a sufficient good to justify it.[89] By positing that man could choose between good and evil without divine intercession, Pelagianism brought into question Christianity's core doctrine of Jesus' act of substitutionary atonement to expiate the sins of mankind.[90] For this reason, Pelagianism became associated with nontrinitarian interpretations of Christianity which rejected the divinity of Jesus,[91] as well as other heresies such as Arianism, Socinianism, and mortalism (which rejected the existence of hell).[64] Augustine argued that if man "could have become just by the law of nature and free will . . . amounts to rendering the cross of Christ void".[89] He argued that no suffering was truly undeserved, and that grace was equally undeserved but bestowed by God's benevolence.[92] Augustine's solution, while it was faithful to orthodox Christology, worsened the problem of evil because according to Augustinian interpretations, God punishes sinners who by their very nature are unable not to sin.[64] The Augustinian defense of God's grace against accusations of arbitrariness is that God's ways are incomprehensible to mere mortals.[64][93] Yet, as later critics such as Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz asserted, asking "it is good and just because God wills it or whether God wills it because it is good and just?", this defense (although accepted by many Catholic and Reformed theologians) creates a God-centered morality, which, in Leibniz' view "would destroy the justice of God" and make him into a tyrant.[94]

Pelagianism and Judaism

One of the most important distinctions between Christianity and Judaism is that the former conventionally teaches justification by faith, while the latter teaches that man has the choice to follow divine law. By teaching the absence of original sin and the idea that humans can choose between good and evil, Pelagianism advocated a position close to that of Judaism.[95] Pelagius wrote positively of Jews and Judaism, recommending that Christians study Old Testament (i.e., the Tanakh) law—a sympathy not commonly encountered in Christianity after Paul.[48] Augustine was the first to accuse Pelagianism of "Judaizing",[96] which became a commonly heard criticism of it.[91][96] However, although contemporary rabbinic literature tends to take a Pelagian perspective on the major questions, and it could be argued that the rabbis shared a worldview with Pelagius, there were minority opinions within Judaism (such as the Essenes) which argued for ideas more similar to Augustine's.[97] Overall, Jewish discourse did not discuss free will and emphasized God's goodness in his revelation of the Torah.[98]

Later responses

Semi-Pelagian controversy

The resolution of the Pelagian controversy gave rise to a new controversy in southern Gaul in the fifth and sixth centuries, retrospectively called by the misnomer "semi-Pelagianism".[99][100] The "semi-Pelagians" all accepted the condemnation of Pelagius, believed grace was necessary for salvation, and were followers of Augustine.[100] The controversy centered on differing interpretations of the verse 1 Timothy 2:4:[59] "For this is good and acceptable in the sight of God our Savior, who desires all men to be saved and to come to the knowledge of the truth."[101] Augustine and Prosper of Aquitaine assumed that God's will is always effective and that some are not saved (i.e., opposing universal reconciliation). Their opponents, based on the tradition of Eastern Christianity, argued that Augustinian predestination contradicted the biblical passage.[100][102] Cassian, whose writings survived, argued for prevenient grace that individuals could accept or reject. Other semi-Pelagians were said to undermine the essential role of God's grace in salvation and argue for a median between Augustinianism and Pelagianism, although these alleged writings are no longer extant.[103] At the Council of Orange in 529, called and presided over by the Augustinian Caesarius of Arles, semi-Pelagianism was condemned but Augustinian ideas were also not accepted entirely: the synod advocated synergism, the idea that human freedom and divine grace work together for salvation.[104][100]

Christians often used "Pelagianism" as a criticism to imply that the target denied God's grace and strayed into heresy.[34] Later Augustinians criticized those who asserted a meaningful role for human free will in their own salvation as covert "Pelagians" or "semi-Pelagians".[18]

Pelagian manuscripts

During the Middle Ages, Pelagius' writings were popular but usually attributed to other authors, especially Augustine and Jerome.[105] Pelagius' Commentary on Romans circulated under two pseudonymous versions, "Pseudo-Jerome" (copied before 432) and "Pseudo-Primasius", revised by Cassiodorus in the sixth century to remove the "Pelagian errors" that Cassiodorus found in it. During the Middle Ages, it passed as a work by Jerome.[106] Erasmus of Rotterdam printed the commentary in 1516, in a volume of works by Jerome. Erasmus recognized that the work was not really Jerome's, writing that he did not know who the author was. Erasmus admired the commentary because it followed the consensus interpretation of Paul in the Greek tradition.[107] The nineteenth-century theologian Jacques Paul Migne suspected that Pelagius was the author, and William Ince recognized Pelagius' authorship as early as 1887. The original version of the commentary was found and published by Alexander Souter in 1926.[107] According to French scholar Yves-Marie Duval, the Pelagian treatise On the Christian Life was the second-most copied work during the Middle Ages (behind Augustine's The City of God) outside of the Bible and liturgical texts.[105][c]

Early modern era

During the modern era, Pelagianism continued to be used as an epithet against orthodox Christians. However, there were also some authors who had essentially Pelagian views according to Nelson's definition.[64] Nelson argued that many of those considered the predecessors to modern liberalism took Pelagian or Pelagian-adjacent positions on the problem of evil.[109] For instance, Leibniz, who coined the word theodicy in 1710, rejected Pelagianism but nevertheless proved to be "a crucial conduit for Pelagian ideas".[110] He argued that "Freedom is deemed necessary in order that man may be deemed guilty and open to punishment."[111] In De doctrina christiana, John Milton argued that "if, because of God's decree, man could not help but fall . . . then God's restoration of fallen man was a matter of justice not grace".[112] Milton also argued for other positions that could be considered Pelagian, such as that "The knowledge and survey of vice, is in this world ... necessary to the constituting of human virtue."[113] Jean-Jacques Rousseau made nearly identical arguments for that point.[113] John Locke argued that the idea that "all Adam's Posterity [are] doomed to Eternal Infinite Punishment, for the Transgression of Adam" was "little consistent with the Justice or Goodness of the Great and Infinite God".[114] He did not accept that original sin corrupted human nature, and argued that man could live a Christian life (although not "void of slips and falls") and be entitled to justification.[111]

Nelson argues that the drive for rational justification of religion, rather than a symptom of secularization, was actually "a Pelagian response to the theodicy problem" because "the conviction that everything necessary for salvation must be accessible to human reason was yet another inference from God's justice". In Pelagianism, libertarian free will is necessary but not sufficient for God's punishment of humans to be justified, because man must also understand God's commands.[115] As a result, thinkers such as Locke, Rousseau and Immanuel Kant argued that following natural law without revealed religion must be sufficient for the salvation of those who were never exposed to Christianity because, as Locke pointed out, access to revelation is a matter of moral luck.[116] Early modern proto-liberals such as Milton, Locke, Leibniz, and Rousseau advocated religious toleration and freedom of private action (eventually codified as human rights), as only freely chosen actions could merit salvation.[117][k]

19th-century philosopher Søren Kierkegaard dealt with the same problems (nature, grace, freedom, and sin) as Augustine and Pelagius,[81] which he believed were opposites in a Hegelian dialectic.[119] He rarely mentioned Pelagius explicitly[81] even though he inclined towards a Pelagian viewpoint. However, Kierkegaard rejected the idea that man could perfect himself.[120]

Contemporary responses

John Rawls was a critic of Pelagianism, an attitude that he retained even after becoming an atheist. His anti-Pelagian ideas influenced his book A Theory of Justice, in which he argued that differences in productivity between humans are a result of "moral arbitrariness" and therefore unequal wealth is undeserved.[121] In contrast, the Pelagian position would be that human sufferings are largely the result of sin and are therefore deserved.[91] According to Nelson, many contemporary social liberals follow Rawls rather than the older liberal-Pelagian tradition.[122]

The conflict between Pelagius and the teachings of Augustine was a constant theme throughout the works of Anthony Burgess, in books including A Clockwork Orange, Earthly Powers, A Vision of Battlements and The Wanting Seed.[123]

Scholarly reassessment

During the 20th century, Pelagius and his teachings underwent a reassessment.[124][53] In 1956, John Ferguson wrote:

If a heretic is one who emphasizes one truth to the exclusion of others, it would at any rate appear that [Pelagius] was no more a heretic than Augustine. His fault was in exaggerated emphasis, but in the final form his philosophy took, after necessary and proper modifications as a result of criticism, it is not certain that any statement of his is totally irreconcilable with the Christian faith or indefensible in terms of the New Testament. It is by no means so clear that the same may be said of Augustine.[125][124]

Thomas Scheck writes that although Pelagius' views on original sin are still considered "one-sided and defective":[53]

An important result of the modern reappraisal of Pelagius's theology has been a more sympathetic assessment of his theology and doctrine of grace and the recognition of its deep rootedness in the antecedent Greek theologians... Pelagius's doctrine of grace, free will and predestination, as represented in his Commentary on Romans, has very strong links with Eastern (Greek) theology and, for the most part, these doctrines are no more reproachable than those of orthodox Greek theologians such as Origen and John Chrysostom, and of St. Jerome.[53]

See also

References

Notes

- ^ According to Marius Mercator, Caelestius was deemed to hold six heretical beliefs:[16]

- Adam was created mortal

- Adam's sin did not corrupt other humans

- Infants are born into the same state as Adam before the fall of man

- Adam's sin did not introduce mortality

- Following God's law enables man to enter the Kingdom of Heaven

- There were other humans, besides Christ, who were without sin

- ^ Scriptural passages cited to support this argument include Deuteronomy 30:15, Ecclesiasticus 15:14–17, and Ezekiel 18:20 and 33:12, 16.[42]

- ^ a b At the Council of Diospolis, On the Christian Life was submitted as an example of Pelagius' heretical writings. Scholar Robert F. Evans argues that it was Pelagius' work, but Ali Bonner disagrees.[108]

- ^ The Hebrew Bible figures claimed as sinless by Pelagius include Abel, Enoch, Melchizedek, Lot, and Noah.[42] At the Synod of Diospolis, Pelagius went back on the claim that other humans besides Jesus had lived sinless lives, but insisted that it was still theoretically possible.[26]

- ^ Scriptural passages cited for the necessity of works include Matthew 7:19–22, Romans 2:13, and Titus 1:1.[42]

- ^ According to Augustine, true virtue resides exclusively in God and humans can know it only imperfectly.[57]

- ^ Scheck and F. Clark summarize the condemned beliefs as follows:

- "Adam's sin injured only himself, so that his posterity were not born in that state of alienation from God called original sin

- It was accordingly possible for man, born without original sin or its innate consequences, to continue to live without sin by the natural goodness and powers of his nature; therefore, justification was not a process that must necessarily take place for man to be saved

- Eternal life was, consequently, open and due to man as a result of his natural good strivings and merits; divine interior grace, though useful, was not necessary for the attainment of salvation."[61]

- ^ The phrase (inimici gratiae) was repeated more than fifty times in Augustine's anti-Pelagian writings after Diospolis.[66]

- ^ Robert Dodaro has a similar list: "(1) that human beings can be sinless; (2) that they can act virtuously without grace; (3) that virtue can be perfected in this life; and (4) that fear of death can be completely overcome".[67]

- ^ Pelagius wrote: "pardon is given to those who repent, not according to the grace and mercy of God, but according to their own merit and effort, who through repentance will have been worthy of mercy".[39]

- ^ This is the opposite of the Augustinian argument against excessive state power, which is that human corruption is such that man cannot be trusted to wield it without creating tyranny, what Judith Shklar called "liberalism of fear".[118]

Citations

- ^ a b c d e f g Harrison 2016, p. 78.

- ^ Kirwan 1998.

- ^ Teselle 2014, pp. 1–2.

- ^ a b Elliott 2011, p. 377.

- ^ a b Keech 2012, p. 38.

- ^ a b Scheck 2012, p. 81.

- ^ a b Wetzel 2001, p. 51.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Bonner 2004.

- ^ a b Beck 2007, pp. 689–690.

- ^ Beck 2007, p. 691.

- ^ Brown 1970, pp. 60–61.

- ^ Bonner 2018, p. 299.

- ^ Teselle 2014, pp. 2, 4.

- ^ Scheck 2012, p. 82.

- ^ a b Teselle 2014, p. 3.

- ^ a b Rackett 2002, p. 224.

- ^ Rackett 2002, pp. 224–225, 231.

- ^ a b c d Scheck 2012, p. 79.

- ^ a b c d e Teselle 2014, p. 5.

- ^ Rackett 2002, pp. 228–229.

- ^ Rackett 2002, p. 230.

- ^ Beck 2007, p. 690.

- ^ Beck 2007, pp. 685–686.

- ^ a b c Rackett 2002, p. 226.

- ^ a b Keech 2012, pp. 39–40.

- ^ a b Rackett 2002, p. 233.

- ^ a b c Teselle 2014, p. 6.

- ^ Beck 2007, p. 687.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Puchniak 2008, p. 123.

- ^ a b c Wetzel 2001, p. 52.

- ^ a b Teselle 2014, p. 7.

- ^ Keech 2012, p. 40.

- ^ Cohen 2016, p. 523.

- ^ a b Rackett 2002, p. 236.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Harrison 2016, p. 81.

- ^ a b c d e f g Harrison 2016, p. 79.

- ^ a b c Chadwick 2001, p. 116.

- ^ a b c d e f Harrison 2016, p. 80.

- ^ a b Visotzky 2009, p. 49.

- ^ a b Visotzky 2009, p. 50.

- ^ Dodaro 2004, pp. 88–89.

- ^ a b c Beck 2007, p. 693.

- ^ Rees 1998, p. 124.

- ^ a b c d e f Visotzky 2009, p. 44.

- ^ a b c d Dodaro 2004, p. 79.

- ^ Dodaro 2004, pp. 79–80.

- ^ a b Dodaro 2004, p. 80.

- ^ a b c Visotzky 2009, p. 48.

- ^ Brown 1970, p. 69.

- ^ Ephesians 5:27

- ^ a b Kirwan 1998, Grace and free will.

- ^ Chadwick 2001, p. 119.

- ^ a b c d e f Scheck 2012, p. 80.

- ^ Bonner 2018, pp. 304–305.

- ^ Augustine of Hippo, Confessions, 3:4

- ^ Dodaro 2004, pp. 109–110.

- ^ Dodaro 2004, p. 111.

- ^ a b c Harrison 2016, p. 82.

- ^ a b Weaver 2014, p. xviii.

- ^ a b c Bonner 2018, p. 302.

- ^ a b Scheck 2012, p. 86.

- ^ Chronister 2020, p. 119.

- ^ Lössl 2019, p. 848.

- ^ a b c d e Nelson 2019, p. 4.

- ^ Scheck 2012, pp. 81–82.

- ^ Rackett 2002, p. 234.

- ^ Dodaro 2004, p. 186.

- ^ Visotzky 2009, p. 43.

- ^ Keech 2012, p. 15.

- ^ Stump 2001, p. 130.

- ^ Dodaro 2004, pp. 187–188.

- ^ Dodaro 2004, p. 191.

- ^ Visotzky 2009, p. 53.

- ^ Squires 2016, p. 706.

- ^ Wetzel 2001, pp. 52, 55.

- ^ Bonner 2018, pp. 303–304.

- ^ Bonner 2018, p. 305.

- ^ Dodaro 2004, p. 86.

- ^ Weaver 2014, p. xix.

- ^ Puchniak 2008, pp. 123–124.

- ^ a b c d Puchniak 2008, p. 124.

- ^ Chadwick 2001, pp. 30–31.

- ^ Stump 2001, pp. 139–140.

- ^ Elliott 2011, p. 378.

- ^ Chadwick 2001, pp. 123–124.

- ^ Levering 2011, p. 47–48.

- ^ James 1998, p. 102.

- ^ James 1998, p. 103. "If one asks, whether double predestination is a logical implication or development of Augustine's doctrine, the answer must be in the affirmative."

- ^ a b Nelson 2019, p. 3.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 3, 51.

- ^ a b c Nelson 2019, p. 51.

- ^ Chadwick 2001, pp. 117–118.

- ^ Stump 2001, p. 139.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 5–6.

- ^ Fu 2015, p. 182.

- ^ a b Visotzky 2009, p. 45.

- ^ Visotzky 2009, p. 59.

- ^ Visotzky 2009, p. 60.

- ^ Weaver 2014, pp. xiv–xv, xviii.

- ^ a b c d Scheck 2012, p. 87.

- ^ 1 Timothy 2:3–4

- ^ Weaver 2014, pp. xv, xix, xxiv.

- ^ Weaver 2014, pp. xviii–xix.

- ^ Weaver 2014, p. xxiv.

- ^ a b Bonner 2018, pp. 288–289.

- ^ Scheck 2012, pp. 91–92.

- ^ a b Scheck 2012, p. 92.

- ^ Bonner 2018, Chapter 7, fn 1.

- ^ Nelson 2019, p. 5.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 2, 5.

- ^ a b Nelson 2019, p. 8.

- ^ Nelson 2019, p. 7.

- ^ a b Nelson 2019, p. 11.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Nelson 2019, p. 15.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 16–18.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 19–20.

- ^ Nelson 2019, p. 21.

- ^ Puchniak 2008, p. 126.

- ^ Puchniak 2008, p. 128.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. 50, 53.

- ^ Nelson 2019, p. 49.

- ^ 'Augustine's Confessions', The International Anthony Burgess Foundation

- ^ a b Beck 2007, p. 694.

- ^ Ferguson 1956, p. 182.

Sources

- Beck, John H. (2007). "The Pelagian Controversy: An Economic Analysis". American Journal of Economics and Sociology. 66 (4): 681–696. doi:10.1111/j.1536-7150.2007.00535.x. S2CID 144950796.

- Bonner, Ali (2018). The Myth of Pelagianism. British Academy Monograph. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-726639-7.

- Clark, Mary T. (2005). Augustine. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4411-8259-3.

- Bonner, Gerald (2004). "Pelagius (fl. c.390–418), theologian". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/21784.

- Brown, Peter (1970). "The Patrons of Pelagius: the Roman Aristocracy Between East and West". The Journal of Theological Studies. 21 (1): 56–72. doi:10.1093/jts/XXI.1.56. ISSN 0022-5185. JSTOR 23957336.

- Chadwick, Henry (2001). Augustine: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-285452-0.

- Chronister, Andrew C. (2020). "Ali Bonner, The Myth of Pelagianism". Augustinian Studies. 51 (1): 115–119. doi:10.5840/augstudies20205115. S2CID 213551127.

- Cohen, Samuel (2016). "Religious Diversity". In Jonathan J. Arnold; M. Shane Bjornlie; Kristina Sessa (eds.). A Companion to Ostrogothic Italy. Leiden, Boston: Brill Publishers. pp. 503–532. ISBN 978-9004-31376-7.

- Dodaro, Robert (2004). Christ and the Just Society in the Thought of Augustine. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-45651-7.

- Elliott, Mark W. (2011). "Pelagianism". In McFarland, Ian A.; Fergusson, David A. S.; Kilby, Karen; Torrance, Iain R. (eds.). The Cambridge Dictionary of Christian Theology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 377–378. ISBN 978-0-511-78128-5.

- Ferguson, John (1956). Pelagius: A Historical and Theological Study. Cambridge: W. Heffer & Sons.

- Fu, Youde (2015). "Hebrew Justice: A Reconstruction for Today". The Value of the Particular: Lessons from Judaism and the Modern Jewish Experience. Leiden: Brill. pp. 171–194. ISBN 978-90-04-29269-7.

- Harrison, Carol (2016). "Truth in a Heresy?". The Expository Times. 112 (3): 78–82. doi:10.1177/001452460011200302. S2CID 170152314.

- James, Frank A. III (1998). Peter Martyr Vermigli and Predestination: The Augustinian Inheritance of an Italian Reformer. Oxford: Clarendon. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

- Keech, Dominic (2012). The Anti-Pelagian Christology of Augustine of Hippo, 396-430. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-966223-4.

- Keeny, Anthony (2009). An Illustrated Brief History of Western Philosophy. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4051-7860-0.

- Kirwan, Christopher (1998). "Pelagianism". Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Taylor & Francis. doi:10.4324/9780415249126-K064-1. ISBN 978-0-415-25069-6.

- Levering, Matthew (2011). Predestination: Biblical and Theological Paths. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-960452-4.

- Lössl, Josef (20 September 2019). "The myth of Pelagianism. By Ali Bonner. (A British Academy Monograph.) Pp. xviii + 342. Oxford–New York: Oxford University Press (for The British Academy), 2018. 978 0 19 726639 7". The Journal of Ecclesiastical History. 70 (4): 846–849. doi:10.1017/S0022046919001283. S2CID 204479402.

- Nelson, Eric (2019). The Theology of Liberalism: Political Philosophy and the Justice of God. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-24094-0.

- Rigby, Paul (2015). The Theology of Augustine's Confessions. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-09492-5.

- Puchniak, Robert (2008). "Pelagius: Kierkegaard's use of Pelagius and Pelagianism". In Stewart, Jon Bartley (ed.). Kierkegaard and the Patristic and Medieval Traditions. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7546-6391-1.

- Rackett, Michael R. (2002). "What's Wrong with Pelagianism?". Augustinian Studies. 33 (2): 223–237. doi:10.5840/augstudies200233216.

- Rees, Brinley Roderick (1998). Pelagius: Life and Letters. Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 978-0-85115-714-6.

- Scheck, Thomas P. (2012). "Pelagius's Interpretation of Romans". In Cartwright, Steven (ed.). A Companion to St. Paul in the Middle Ages. Leiden: Brill. pp. 79–114. ISBN 978-90-04-23671-4.

- Squires, Stuart (2016). "Jerome on Sinlessness: a Via Media between Augustine and Pelagius". The Heythrop Journal. 57 (4): 697–709. doi:10.1111/heyj.12063.

- Teselle, Eugene (2014). "The Background: Augustine and the Pelagian Controversy". In Hwang, Alexander Y.; Matz, Brian J.; Casiday, Augustine (eds.). Grace for Grace: The Debates after Augustine and Pelagius. Washington, D.C.: Catholic University of America Press. pp. 1–13. ISBN 978-0-8132-2601-9.

- Stump, Eleonore (2001). "Augustine on free will". In Stump, Eleonore; Kretzmann, Norman (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Augustine. New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 124–147. ISBN 978-1-1391-7804-4.

- Visotzky, Burton L. (2009). "Will and Grace: Aspects of Judaising in Pelagianism in Light of Rabbinic and Patristic Exegesis of Genesis". In Grypeou, Emmanouela; Spurling, Helen (eds.). The Exegetical Encounter Between Jews and Christians in Late Antiquity. Leiden: Brill. pp. 43–62. ISBN 978-90-04-17727-7.

- Weaver, Rebecca (2014). "Introduction". In Hwang, Alexander Y.; Matz, Brian J.; Casiday, Augustine (eds.). Grace for Grace: The Debates after Augustine and Pelagius. Washington, D.C.: Catholic University of America Press. pp. xi–xxvi. ISBN 978-0-8132-2601-9.

- Wetzel, James (2001). "Predestination, Pelagianism, and foreknowledge". In Stump, Eleonore; Kretzmann, Norman (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Augustine. New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 49–58. ISBN 978-1-1391-7804-4.

Further reading

- Bonner, Gerald (2002). "The Pelagian controversy in Britain and Ireland". Peritia. 16: 144–155. doi:10.1484/J.Peri.3.483.

- Brown, Peter (1968). "Pelagius and his Supporters: Aims and Environment". The Journal of Theological Studies. XIX (1): 93–114. doi:10.1093/jts/XIX.1.93. JSTOR 23959559.

- Clark, Elizabeth A. (2014). The Origenist Controversy: The Cultural Construction of an Early Christian Debate. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-6311-2.

- Cyr, Taylor W.; Flummer, Matthew T. (2018). "Free will, grace, and anti-Pelagianism". International Journal for Philosophy of Religion. 83 (2): 183–199. doi:10.1007/s11153-017-9627-0. ISSN 1572-8684. S2CID 171953180.

- Dauzat, Pierre-Emmanuel [in French] (2010). "Hirschman, Pascal et la rhétorique réactionnaire: Une analyse économique de la controverse pélagienne" [Hirschman, Pascal and reactionary rhetoric: An economic analysis of the Pelagian controversy]. The Tocqueville Review/La revue Tocqueville (in French). 31 (2): 133–154. doi:10.1353/toc.2010.0009. ISSN 1918-6649. S2CID 145615057.

- Dodaro, Robert (2004). ""Ego miser homo": Augustine, The Pelagian Controversy, and the Paul of Romans 7:7-25". Augustinianum. 44 (1): 135–144. doi:10.5840/agstm20044416.

- Evans, Robert F. (2010) [1968]. Pelagius: Inquiries and Reappraisals. Eugene: Wipf and Stock. ISBN 978-1-60899-497-7.

- Lamberigts, Mathijs [in Dutch] (2002). "Recent Research Into Pelagianism With Particular Emphasis on the Role of Julian of Aeclanum". Augustiniana. 52 (2/4): 175–198. ISSN 0004-8003.

- Markus, Gilbert (2005). "Pelagianism and the 'Common Celtic Church'" (PDF). Innes Review. 56 (2): 165–213. doi:10.3366/inr.2005.56.2.165.

- Nunan, Richard (2012). "Catholics and evangelical protestants on homoerotic desire: the intellectual legacy of Augustinian and Pelagian theories of human nature". Queer Philosophy. Brill | Rodopi. pp. 329–352. doi:10.1163/9789401208352_039. ISBN 978-94-012-0835-2.

- Rees, Brinley Roderick (1988). Pelagius: A Reluctant Heretic. Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 0-85115-503-0.

- Scholl, Lindsey Anne (2011). Elizabeth DePalma Digeser (ed.). The Pelagian Controversy: A Heresy in its Intellectual Context (PhD thesis). University of California, Santa Barbara. ISBN 978-1-249-89783-5. ProQuest 3482027.

- Squires, Stuart (2013). Philip Rousseau (ed.). Reassessing Pelagianism: Augustine, Cassian, and Jerome on the Possibility of a Sinless Life (PhD thesis). Catholic University of America.

- Squires, Stuart (2019). The Pelagian Controversy: An Introduction to the Enemies of Grace and the Conspiracy of Lost Souls. Eugene: Wipf and Stock. ISBN 978-1-5326-3781-0.

- Wermelinger, Otto (1975). Rom und Pelagius: die theologische Position der römischen Bischöfe im pelagianischen Streit in den Jahren 411-432 [Rome and Pelagius: the theological position of the Roman bishops during the Pelagian controversy, 411–432] (in German). A. Hiersemann. ISBN 978-3-7772-7516-1.