Paleontology in Michigan

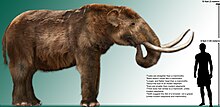

Paleontology in Michigan refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Michigan. During the Precambrian, the Upper Peninsula was home to filamentous algae. The remains it left behind are among the oldest known fossils in the world. During the early part of the Paleozoic Michigan was covered by a shallow tropical sea which was home to a rich invertebrate fauna including brachiopods, corals, crinoids, and trilobites. Primitive armored fishes and sharks were also present. Swamps covered the state during the Carboniferous. There are little to no sedimentary deposits in the state for an interval spanning from the Permian to the end of the Neogene. Deposition resumed as glaciers transformed the state's landscape during the Pleistocene. Michigan was home to large mammals like mammoths and mastodons at that time. The Holocene American mastodon, Mammut americanum, is the Michigan state fossil. The Petoskey stone, which is made of fossil coral, is the state stone of Michigan.

Prehistory

Paleozoic

Michigan's fossil record stretches as far back as the Precambrian.[1] Blue-green algae remains from this age were preserved between Copper Harbor and Eagle Harbor on the shoreline of Lake Superior.[1] By the early part of the Paleozoic, Michigan was located in equatorial latitudes.[2] Michigan was at least partly covered by seawater during the Cambrian.[3] Life in Michigan's Cambrian seas included some brachiopods, cephalopods, gastropods, and trilobites. Trilobites would become more common in Michigan as the Paleozoic progressed.[1]

During the ensuing Ordovician, Michigan remained inundated by seawater.[2] Brachiopods flourished and are among the most common fossils of the period in Michigan.[1] Cephalopods were also common in the Ordovician.[1] One straight shelled species was more than fifteen feet long.[1] Crinoids were also present. So were blastoids, but they were not as common as the others.[1]

Michigan's Middle Ordovician fossil record does not preserve any fish, however some strata of that age found in the Upper Peninsula correspond to deposits of that age on Ontario's St. Joseph Island where such finds have been made. Since pieces of the bony armor that once embedded in the skin of the fish Astraspis were preserved at St. Joseph's, the similarly aged nearby Middle Ordovician rocks of the Upper Peninsula are also likely to preserve similar fish fossils. If this supposition is correct, then Michigan's fish fossil record may go back as far 460 million years ago.[4]

In the next period, the Silurian, Michigan continued to be a marine environment.[2] Tabulate and tetra- corals appear.[5] Accumulations of these corals up to seventy feet thick are known from places like Engadine, Gould City, and Trout Lake.[5]

During the following period, the sea still covered Michigan.[2] Crinoids were very abundant in Michigan during the Devonian.[5] Brachiopods are also found in the Devonian, but are less common at that time than they were during the Ordovician.[1] Bryozoans and corals were also present.[5] Plant fossils of this age have been found but are relatively rare. Among which were fossils likely attributable to the tree Callixylon.[5]

The Middle Devonian is the best documented geologic epoch in the state's Paleozoic fish fossil record. Such discoveries have occurred in both the northern region of the Lower Peninsula and in the southeast. The northern region has been more productive for Middle Devonian fish fossils, with Alpena, Charlevoix, Emmet, and Presque Isle counties all contributing discoveries. The less abundant Middle Devonian fishes of southeast Michigan are known from the rocks of Arenac, Calhoun, Huron, Jackson, and Kent counties.[4]

A significant proportion of Michigan's Devonian fish were placoderms. Usually Michigan strata of this age only preserve their bony armor and gnathal bones. There are three main groups of placoderms that have been found in Michigan, the antiarchs, arthrodires, and ptyctodonts.[4] Arthrodires reported from Michigan rocks include Dunkleosteus, Holonema, Protitanichthys, and Titanichthys.[4] Ptyctodus is a representative example of a Michiganian ptyctodont. Bothriolepis is the only known antiarch from Michigan.[6]

Acanthodian fossils from Michigan are typically isolated specimens of the spines that supported their fins and these are commonly broken. However, the best preserved specimens of Michiganian acanthodians reveal large eyed generalists who ate plankton in the mid-level of the water column using teeth with multiple points.[6]

Sharks swam over Michigan during the Devonian. Since shark skeletons were cartilaginous and lacked hard parts conducive to fossilization, typically only their spines and teeth remain. Despite occurring so early in the fossil record, Michigan's cladoselachian sharks closely resembled modern forms. Fossil shark spines found in Michigan are usually the remains of ctenacanths and cladodonts. Bradyodont shark teeth have also been discovered in Michigan, however, it's also possible that these teeth were shed by animals more closely related to holocephalans than true sharks.[6] Tabulate and tetra- corals disappeared from Michigan during the Devonian.[5]

During the Early Carboniferous the sea covering Michigan began a gradual withdrawal.[2] Sharks persisted as members of Michigan's fish communities during the Mississippian.[6] Mississippian fish fossils have been discovered in Arenac, Calhoun, Huron, Jackson, and Kent counties.[4] Gastropod fossils persisted until the end of the Mississippian.[1] Brachiopods further persisted into the Mississippian but did not become as abundant as they were during the Ordovician.[1]

Swamps formed across the state as the Carboniferous period continued and the sea left the state.[2] These swamps were full of ferns and scale trees.[2] Xenacanth fossils are known from such deposits.[6] Plant fossils are common from Michigan rocks of Pennsylvanian age. The flora of Michigan back then included club moss trees, ferns, and horsetails.[5] Contemporary vegetation was preserved in the Midland and Saginaw regions.[7] Fossil lungfish burrows are another interesting find from the Pennsylvanian coal swamp deposits near Grand Ledge in Clinton County but these tend to be poorly preserved. Nevertheless, such fossils are an uncommon find.[6] Other Pennsylvanian fish fossils were preserved in Clinton and Saginaw counties of the central part of the state.[4]

During the Permian, sediments were being eroded away from Michigan rather than deposited.[2] As such there are no local rocks of that age. As such, no Permian fossils are known from Michigan.[1]

Mesozoic

The ensuing Triassic period of the Mesozoic era is missing from the state's rock record for the same reason as the Permian. During the Jurassic, local plants left behind spores that would later fossilize. However, these are the only known local fossil from the time period since rocks of this age are buried deep underground and accessible only through core sample drilling. Like the Permian and Triassic, Cretaceous rocks are altogether absent from the state.[2] No dinosaur fossils are known from Michigan as there aren't any surface rocks of the right age to preserve them.[8]

Cenozoic

The same erosional forces responsible for the Permian and Mesozoic gaps in Michigan's rock record were active during the ensuing Paleogene and Neogene periods of the Cenozoic era.[2] As such, no Cenozoic fossils older than the Pleistocene are known from Michigan.[1] Nevertheless, Michigan has many deposits made during the Quaternary period. At that time the state's entire landscape was reworked by glacial activity.[2] The area now submerged under the Great Lakes had been a lowland river system. As glaciers advanced and retreated they carved these areas into the Great Lakes and filled them as they melted.[3] The preservation of fossils in Michigan resumed when the last glaciers withdrew from the state. Between 17,000 and 13,000 years ago, much of Michigan's icy covering had disappeared. After the glaciers melted much of the state was covered in large lakes made of glacial meltwater. By 10,000 years ago many of these lakes had dried. Forests of spruce and fir grew on the newly exposed terrain. By the time about 2,000 years had elapsed, pine trees became the dominant members composing Michigan's forest.[9] The most common mammals in Michigan's Pleistocene fossil record were caribou, elk, Jefferson mammoths, American mastodons, and woodland muskoxen. Less common members of Michigan's fossil record included black bears, giant beavers, white-tailed deer, Scott's moose, muskrats, peccaries, and meadow voles.[10]

History

Among Michigan's early significant fossil finds was the 1839 discovery of the state's first scientifically documented American mastodon remains.[11] Later in the 19th century was the 1877 discovery of five Pleistocene peccaries (Platygonus compressus) in an Ionia County peat bog located near the town of Belding. The find was credited to L. N. Tuttle and the specimens are now catalogued as UMMP 7325.[12]

Near the beginning of the 20th century, in 1903, Tuttle's peccaries were finally described for the scientific literature by Wagner.[12] In 1914, Ezra Smith made another interesting Pleistocene-aged discovery, finding the fossil penis bone of a Late Pleistocene walrus seven miles northwest of Gaylord. The specimen was referred to the genus Odobenus and is now catalogued as UMMAA 490. It would not be reported to the scientific literature until a 1925 paper by Hinsdale, however.[13]

Major events from the second decade of the twentieth century in Michigan paleontology include a 1923 paper by O. P. Hay who reported the presence of two identifiable species and one indeterminate form of mammoth whose fossils had been found in Michigan.[14] Interesting whale fossils were also discovered and described from Michigan around this time. In 1927 excavations for a new schoolhouse in Oscoda turned up a Late Pleistocene fossil rib that may have belonged to a bowhead whale of the genus Balaena. The specimen is now catalogued as UMMP 11008.[15] 1930 saw Hussey publish the first scientific paper on the Michiganian whale fossils curated by the University of Michigan Museum of Paleontology.[16]

The fourth decade of the twentieth century was kicked off by the 1940 announcement by MacAlpin that a total of 117 American mastodon specimens had been discovered in Michigan.[11] Later in the decade, a third lower premolar from a Pleistocene elk was discovered in Berrien County in October, 1949.[17]

The 1950s saw paleontological attention return to Michigan's whale fossils. In 1953, Handley tentatively referred the rib discovered in Oscoda during the 1927 schoolhouse excavation to the genus Balaena.[15] He also reported the discovery of an Arkonan-aged[clarification needed (possibly referring to Thedford-Arkona region)] rorqual rib of the genus Balaenoptera. The fossil had been discovered upright in the sand during the excavation of a cellar in Genesee County.[18] Handley also reported the discovery of another walrus fossil, a skull catalogued as UMMP 32453 found in a Mackinac Island gravel deposit.[13] Handley also reported the discovery of sperm whale ribs and a vertebra from Lenawee County.[19]

In August of 1961, Larry Kickels collected the third right upper molar of a Jefferson mammoth from a gravel layer 100 feet below the surface of Berrien County, near the town of Watervliet.[14] The next year several major events occurred relating to the Pleistocene proboscidean fossils. On September 18 Larry Kramer discovered a lower mastodon molar now catalogued as GRPM 12540 in Paris Township along Buck Creek. Also in 1962, Skeels reported that since MacAlpin's 1940 review of Michigan mastodon discoveries 49 new finds had been made.[11] He also performed the first census of local mammoth remains, noting that 32 Jefferson mammoths had been discovered in Michigan.[14] Hatt also formally described a partial mastodon skull now catalogued as CIPS 827 which had been discovered in Pontiac.[11] 1962 was also the year a Jefferson mammoth was discovered in Gratiot County.[14]

In 1963, Oltz and Kapp reported the 1962 Gratiot County mammoth discovery to the scientific literature. Also, Hatt reported the discovery of a mammoth molar in Oakland County to the scientific literature.[14] The next year, in May, 1964 Fred Berndt discovered lower jaw fragments and the second right molar of a lower mastodon jaw, in Lincoln Township.[20] The remains are now catalogued as UMMP 49425.[21]

More recent events relevant to paleontology in Michigan include the 1965 designation of the Petoskey stone, which is made of fossil coral, as the state stone of Michigan. Also relevant was the 2002 designation of the American mastodon, Mammut americanum as the Michigan state fossil.

People

Births

- Walter Auffenberg was born on February 6, 1928, in Detroit.

- Robert L. Carroll was born on May 5, 1938, in Kalamazoo.

- William R. Hammer was born in Detroit.

- Nicholas Hotton III was born in 1920 or 1921.

Deaths

- Chester A. Arnold died on November 19, 1977, in Ann Arbor at age 76.

- Claude W. Hibbard died in Ann Arbor on October 9, 1973.

Natural history museums

- A. E. Seaman Mineral Museum, Houghton

- Central Michigan University Museum of Cultural and Natural History, Mount Pleasant

- Cranbrook Institute of Science, Bloomfield Hills

- Grand Rapids Public Museum, Grand Rapids

- Kingman Museum, Battle Creek

- Michigan State University Museum, East Lansing

- University of Michigan Exhibit Museum of Natural History, Ann Arbor

Notable clubs and associations

- Friends of the University of Michigan Museum of Paleontology, Inc.[22]

- Michigan Mineralogical Society

See also

- Paleontology in Indiana

- Paleontology in Ohio

- Paleontology in Wisconsin

- Timeline of paleontology in Michigan

Footnotes

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Murray (1974); "Michigan", p. 157.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Brandt Springer, & Scotchmoor (2006); "Paleontology and geology".

- ^ a b Murray (1974); "Michigan", p. 159.

- ^ a b c d e f Koch & Stearley (1987); "Paleozoic Fish", p. 170.

- ^ a b c d e f g Murray (1974); "Michigan", p. 158.

- ^ a b c d e f Koch & Stearley (1987); "Paleozoic Fish", p. 171.

- ^ Kchodl (2006); "Plants", p. 97.

- ^ Mihelich, (2006); p. 1.

- ^ Koch & Stearley (1987); "The Pleistocene Record", p. 171.

- ^ Koch & Stearley (1987); "The Pleistocene Record", p. 172.

- ^ a b c d Wilson (1967); "Mammut americanum (Kerr). American Mastodon", p. 213.

- ^ a b Wilson (1967); "Platygonus compressus (Le Conte). Peccary", p. 215.

- ^ a b Wilson (1967); "Odobenus sp.", p. 212.

- ^ a b c d e Wilson (1967); "Mammuthus jeffersoni (Osborn). Jefferson Mammoth", p. 214.

- ^ a b Wilson (1967); "? Balaena sp.", p. 213.

- ^ Wilson (1967); "Whales", p. 212.

- ^ Wilson (1967); "Cervus canadensis Erxleben. Elk", p. 215.

- ^ Wilson (1967); "Balaenoptera sp. Rorquals", p. 213.

- ^ Wilson (1967); "Physeter sp. Sperm Whale", p. 212.

- ^ Holman, J. Alan; Fisher, Daniel C.; Kapp, Ronald O. (September 22, 2003). "Recent discoveries of fossil vertebrates in the lower Peninsula of Michigan". Michigan Academician. XVIII (3): 431–63. Retrieved August 18, 2017.

- ^ Wilson (1967); "Mammut americanum (Kerr). American Mastodon", p. 214.

- ^ Garcia & Miller (1998); "Appendix C: Major Fossil Clubs", p. 198.

References

- Brandt, Danita; Springer, Dale; Scotchmoor, Judy (July 21, 2006). "Michigan, US". The Paleontology Portal. Retrieved December 1, 2012.

- Garcia, Frank A.; Miller, Donald S. (1998). Discovering Fossils (1st ed.). Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books. ISBN 0811728005.

- Kchodl, Joseph J.; Chase, Roger (2006). The Complete Guide to Michigan Fossils. Ann Arbor, MI: The University of Michigan Press. ISBN 9780472021833.

- Koch, PL; Stearley, RF (1987). "Fossil vertebrates of Michigan". Rocks and Minerals. 62: 169–174. doi:10.1080/00357529.1987.11762649. ISSN 0035-7529.

- Mihelich, Peggy (August 25, 2006). "It's Real Life CSI for Dinosaur Detectives". CNN Tech. Archived from the original on June 3, 2012. Retrieved July 31, 2012.

- Murray, Marian (1974). Hunting for Fossils: A Guide to Finding and Collecting Fossils in All 50 States. Collier Books. p. 348. ISBN 9780020935506.

- Wilson, R. L. (1967). "The Pleistocene Vertebrates of Michigan". Papers of the Michigan Academy of Science Arts and Letters. 52: 197–257.