The Boat Race

| |

| Event information | |

|---|---|

| Race area | The Championship Course River Thames, London[a] |

| Dates | 1829, annual since 1856 |

| Sponsor | Gemini (since 2021)[1] |

| Competitors | CUBC, OUBC |

| Distance | 4.2 miles (6.8 km) |

| First race | 10 June 1829 |

| Website | www |

| Results | |

| Winner (2024) | Cambridge |

The Boat Race is an annual set of rowing races between the Cambridge University Boat Club and the Oxford University Boat Club, traditionally rowed between open-weight eights on the River Thames in London, England. It is also known as the University Boat Race and the Oxford and Cambridge Boat Race.

The men's race was first held in 1829 and has been held annually since 1856, except during the First and Second World Wars (although unofficial races were conducted) and the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. The first women's event was held in 1927, and the Women's Boat Race has been an annual event since 1964. Since 2015, the women's race has taken place on the same day and course, and since 2018 the combined event of the two races has been referred to as "The Boat Race".

The Championship Course has hosted the vast majority of the races. Covering a 4.2-mile (6.8 km) stretch of the Thames in West London, from Putney to Mortlake, it is over three times the distance of an Olympic race. Members of both crews are traditionally known as blues and each boat as a "Blue Boat", with Cambridge in light blue and Oxford in dark blue. As of the 2024 race, Cambridge has won the men's race 87 times to Oxford's 81 times, with one dead heat, and has led Oxford in cumulative wins since 1930. In the women's race, Cambridge has won the race 47 times to Oxford's 30 times, and has led Oxford in cumulative wins since 1966. A reserve boat race has been held since 1965 for the men and since 1966 for the women.

In most years over 250,000 people watch the race from the banks of the river. In 2009, a record 270,000 people watched the race live.[2] The race is broadcast internationally on television;[3] in 2014, 15 million people watched the race on television.[4]

History of the men's race

Origin

The tradition was started in 1829 by Charles Merivale, a student at St John's College, Cambridge, and his Old Harrovian school friend Charles Wordsworth who was studying at Christ Church, Oxford.[5] The University of Cambridge challenged the University of Oxford to a race at Henley-on-Thames but Oxford won easily.[5] Oxford raced in dark blue because five members of the crew, including the stroke, were from Christ Church, then Head of the River, whose colours were dark blue.[6]

The second race was in 1836, with the venue moved to a course from Westminster to Putney. Over the next two years, there was disagreement over where the race should be held, with Oxford preferring Henley and Cambridge preferring London.[6] Following the official formation of the Oxford University Boat Club, racing between the two universities resumed in 1839 on the Tideway and the tradition continues to the present day, with the loser challenging the winner to a rematch annually.[7]

Since 1856, the race has been held every year, except for the years 1915 to 1919 due to World War I, 1940 to 1945, due to World War II,[8] and in 2020 due to COVID-19 pandemic policy.[9]

1877 dead heat

The race in 1877 was declared a dead heat.[10] Both crews finished in a time of 24 minutes and 8 seconds in bad weather.[11] The verdict of the race judge, John Phelps, is considered suspect because he was reportedly over 70 and blind in one eye.[11][12][13] Rowing historian Tim Koch, writing in the official 2014 Boat Race Programme, notes that there is "a very big and very entrenched lie" about the race, including the claim that Phelps had announced "Dead heat ... to Oxford by six feet" (the distance supposedly mentioned by Phelps varies according to the telling).[14]

Phelps's nickname "Honest John" was not an ironic one, and he was not (as is sometimes claimed) drunk under a bush at the time of the finish. He did have to judge who had won without the assistance of finish posts (which were installed in time for the next year's race).[13] Some newspapers had believed Oxford won a narrow victory but their viewpoint was from downstream; Phelps considered that the boats were essentially level with each surging forward during the stroke cycle. With no clear way to determine who had surged forward at the exact finish line, Phelps could only pronounce it a dead heat. Koch believes that the press and Oxford supporters made up the stories about Phelps later, which Phelps had no chance to refute.[14]

Oxford, partially disabled, were making effort after effort to hold their rapidly waning lead, while Cambridge, who, curiously enough, had settled together again, and were rowing almost as one man, were putting on a magnificent spurt at 40 strokes to the minute, with a view of catching their opponents before reaching the winning-post. Thus struggling over the remaining portion of the course, the two eights raced past the flag alongside one another, and the gun fired amid a scene of excitement rarely equalled and never exceeded. Cheers for one crew were succeeded by counter-cheers for the other, and it was impossible to tell what the result was until the Press boat backed down to the Judge and inquired the issue. John Phelps, the waterman, who officiated, replied that the noses of the boats passed the post strictly level, and that the result was a dead heat.[15]

Cancellations during World Wars

Because of World War I and II, the race was not held in 1915–1919 and 1940–1945. On 12 January 1915, The Daily Telegraph announced that the annual race was cancelled due to men leaving for war, "for every available oarsman, either Fresher or Blue, has joined the colours."[16]

1959 Oxford mutiny

In 1959 some of the existing Oxford blues attempted to oust president Ronnie Howard and coach Jumbo Edwards.[17] However, their attempt failed when Cambridge supported the president.[17] Three of the dissidents returned and Oxford went on to win by six lengths.[18]

1987 Oxford mutiny

Following defeat in the previous year's race, Oxford's first in eleven years, American Chris Clark was determined to gain revenge: "Next year we're gonna kick ass ... Cambridge's ass. Even if I have to go home and bring the whole US squad with me."[19] He recruited another four American post-graduates: three international-class rowers (Dan Lyons, Chris Huntington and Chris Penny) and a cox (Jonathan Fish),[20][21] in an attempt to put together the fastest Boat Race crew in the history of the contest.[22]

When you recruit mercenaries, you can expect some pirates.

Disagreements over the training regime of Dan Topolski, the Oxford coach ("He wanted us to spend more time training on land than water!", lamented Lyons[20]), led to the crew walking out on at least one occasion, and resulted in the coach revising his approach.[24] A fitness test between Clark and club president Donald Macdonald (in which Clark triumphed) resulted in a call for Macdonald's removal; it was accompanied with a threat that the Americans would refuse to row should Macdonald remain in the crew.[24] As boat club president, Macdonald "had absolute power over selection", and when he announced that Clark would row on starboard, his weaker side, Macdonald would row on the port side and Tony Ward was to be dropped from the crew entirely, the American contingent mutinied.[21] After considerable negotiation and debate, much of it conducted in the public eye, Clark, Penny, Huntington, Lyons and Fish were dropped and replaced by members of Oxford's reserve crew, Isis.[21]

The race was won by Oxford by four lengths,[10] despite Cambridge being favourites.[25]

In 1989 Topolski and author Patrick Robinson's book about the events, True Blue: The Oxford Boat Race Mutiny, was published. Seven years later, a film based on the book was released. Alison Gill, the then-president of the Oxford University Women's Boat Club, wrote The Yanks at Oxford, in which she defended the Americans and claimed Topolski wrote True Blue in order to justify his own actions.[24] River and Rowing Museum founder Chris Dodd described True Blue as "particularly offensive" yet also wrote "[Oxford] lacked the power, the finesse—basically everything the pre-mutiny line-up had going for it."[21]

2012 disruption

In the 2012 race, after almost three-quarters of the course had been rowed, the race was halted for over 30 minutes when a lone protester, Australian Trenton Oldfield, entered the water from Chiswick Eyot and deliberately swam between the boats near Chiswick Pier with the intention of protesting against spending cuts, and what he saw as the erosion of civil liberties and a growing culture of elitism within British society.[26] Once he was spotted by assistant umpire Sir Matthew Pinsent, both boats were required to stop for safety reasons. Once restarted, the boats clashed and the oar of Oxford crewman Hanno Wienhausen was broken in half with the blade snapped off. The race umpire John Garrett judged the clash to be Oxford's fault and allowed the race to continue. Cambridge quickly took the lead and went on to win the race. The Oxford crew entered a final appeal to the umpire which was quickly rejected; and Cambridge were confirmed as winners in the first race since 1849 that a crew had won the boat race without an official recorded winning time.[10] After the end of the race Oxford's bow man, Alex Woods, received emergency treatment after collapsing in the boat from exhaustion. Because of the circumstances, the post-race celebrations by the winning Cambridge crew were unusually muted and the planned award ceremony was cancelled.[27][28][29][30]

2020 cancellation

Like other sports events, the 2020 boat race was cancelled because of COVID-19 pandemic policy.[31]

2021 relocation

The 2021 races were held on the Great Ouse at Ely in Cambridgeshire, over a shorter straight course of 4.9 kilometres (3.0 mi).[32] This was due to the safety issues of Hammersmith Bridge, as well as restrictions due to the COVID-19 pandemic still being in force.[33]

The 2022 Boat Race returned to the Thames and the traditional course between Putney and Mortlake.[34]

Sinkings

In the 1912 race, run in extremely poor weather and high winds, both crews sank. Oxford rowed into a significant early lead, but began taking on water, and made for the bank shortly after passing Hammersmith Bridge to empty the boat out: although they attempted to restart, the race was abandoned at this point because Cambridge had also sunk while passing the Harrods Depository.[35]

Cambridge also sank in 1859 and in 1978, while Oxford did so in 1925,[36][37][38] and again in 1951; the 1951 race was re-rowed on the following Monday.[39] In 1984 the Cambridge boat sank after colliding with a barge before the start of the race, which was then rescheduled for the next day.[40] In 2016, at Barnes Bridge, Cambridge women began to sink but gradually recovered to complete the race.[41]

History of the women's race

From the first women's event in 1927, the Women's Boat Race was run separately from the men's event until 2015. There was significant inequality between the two events.[42] Changes in recent years, arising significantly from the sponsorship of Newton Investment Management,[43][44] have made the two races more equal: both events have been held together on The Tideway since 2015, and there are new training facilities for the women, comparable to those of the men, since 2016.[45][46][47]

Courses

The 1st Boat Race took place at Henley-on-Thames in 1829 but the event was subsequently officially held along the Thames, mostly the Championship Course, except the 2021 race which was moved to the River Great Ouse due the COVID-19 pandemic and safety concerns under Hammersmith Bridge.[48] Unofficial races were held during the Second World War at various locations.[49][50][51][52]

| Year(s) | Location | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1829 | Henley-on-Thames | 2.25-mile (3.62 km) stretch of the River Thames between Hambleden Lock and Henley Bridge |

| 1836 to 1842 | Westminster to Putney | 5.75-mile (9.25 km) stretch of the River Thames between Westminster Bridge and Putney Bridge |

| 1845, 1849–1854, 1857–1862, 1864–2019, 2022– | Championship Course | 4-mile-374-yard (6,779 m) stretch of the River Thames between Putney to Mortlake |

| 1846, 1856, 1863 | Championship Course | 4-mile-374-yard (6,779 m) stretch of the River Thames between Mortlake to Putney |

| 2021 | River Great Ouse | 5,350-yard (4.89 km) stretch of river between Adelaide Bridge and Sandhill Bridge |

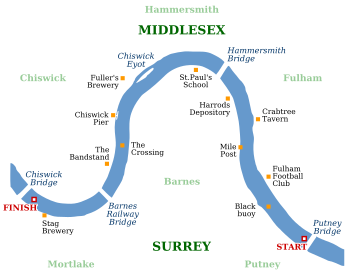

The Championship Course

The Championship Course is 4 miles and 374 yards (6.779 km) from Putney to Mortlake,[53] passing Hammersmith and Barnes, following an S shape, east to west. The start and finish are marked by the University Boat Race Stones on the south bank. The clubs' presidents toss a coin (the 1829 sovereign) before the race for the right to choose which side of the river (station) they will row on: their decision is based on the weather, the speed of the flood tide, and how the three bends in the course might favour their crew's pace. The north station ('Middlesex') has the advantage of the first and last bends, and the south ('Surrey') station the other, longer bend.[citation needed]

During the race the coxes compete for the fastest current, which lies at the deepest part of the river, frequently leading to clashes of blades and warnings from the umpire. A crew that gets a lead of more than a boat's length can cut in front of their opponent, making it extremely difficult for the trailing crew to gain the lead. For this reason the tactics of the race are generally to go fast early on, and it is unusual for the leading crew to change after halfway (though this happened in 2003, 2007 and 2010).[citation needed]

Save for three Victorian instances, each race is rowed westwards, but starts during the incoming (known as flood) tide, so that the crews are rowing with, not against, the fast stream.[54] At the conclusion of the race, the boats come ashore at the shared shingle of the two boat clubs in Chiswick,[55] a few metres west of Chiswick Bridge. Here, shortly after the race, the Boat Race trophy is presented to the winning crew. It is traditional for the winning side to throw their cox into the Thames to celebrate their achievement.[56]

Unofficial courses

In addition, there were four unofficial boat races held during the Second World War away from London.[57] None of those competing were awarded blues, and these races are not included in the official list:

- 1940, 1945 – Henley-on-Thames [citation needed]

- 1943 – Sandford-on-Thames[57]

- 1944 – River Great Ouse, Ely: Littleport to Queen Adelaide[58]

Women's Boat Race courses

During its early years (1927 to 1976 with several gaps) the Women's Boat Race alternated between The Isis in Oxford and the River Cam in Cambridge over a distance of about 1,000 yards.[59][60][61] On two occasions, in 1929 and 1935, the race was held on the Tideway in London.[59][62][63] Unlike the men's race, the official women's race continued in most years through the Second World War.[62]

From 1977 to 2014, the Women's Boat Race was usually held on a 2000-metre course as part of the Henley Boat Races. However, in 2013 the entire Henley Boat Races were moved to Dorney Lake due to rough water at Henley.[64][65] In 2021, the race was held on the River Great Ouse from Ely, Cambridgeshire, along with the men's race.[66]

Media coverage

The race first appeared in a short film of the 1895 race entitled The Oxford and Cambridge University Boat Race, directed and produced by Birt Acres. Consisting of a single shot of around a minute, it was the first film to be commercially screened in the UK outside London.[67] The event is now a British national institution, and is televised live each year. The women's race has received television coverage and grown in popularity since 2015, attracting a television audience of 4.8 million viewers that year.[68][69][70] BBC Television first covered the men's race in 1938, the BBC having covered it on radio since 1927. For the 2005 to 2009 races, the BBC lost the television rights to ITV, after 66 years, but it returned to the corporation in 2010.[71] Ethnographer Mark de Rond described the training, selection, and victory of the 2007 Cambridge crew in The Last Amateurs: To Hell and Back with the Cambridge Boat Race Crew.[72]

Competitors

Men's race

Many notable individuals have participated in the Boat Race, including those of an Olympic standard. Four-time Olympic gold medallist Sir Matthew Pinsent, rowed for Oxford in 1990, 1991, and 1993. Olympic gold medallists from 2000 – James Cracknell (Cambridge 2019), Tim Foster (Oxford 1997), Luka Grubor (Oxford 1997), Andrew Lindsay (Oxford 1997, 1998, 1999) and Kieran West (Cambridge 1999, 2001, 2006, 2007), 2004 – Ed Coode (Oxford 1998), and 2008 – Jake Wetzel (Oxford 2006) and Malcolm Howard (Oxford 2013, 2014) have also rowed for their university.[73]

Other famous participants include Andrew Irvine (Oxford 1922, 1923), Lord Snowdon (Cambridge 1950), Colin Moynihan (Oxford 1977), actor Hugh Laurie (Cambridge 1980), TV presenter Dan Snow (Oxford 1999, 2000, 2001) and Conspicuous Gallantry Cross recipient Robin Bourne-Taylor (Oxford 2001, 2002, 2003, 2005).[73]

Academic status

Oxford University does not offer sport scholarships at entry; student-athletes are not admitted differently to any other students and must meet the academic requirements of the university, with sport having a neutral effect on any application.[74] Likewise, bursaries and scholarship opportunities for athletes at the University of Cambridge are only open to those students who have already been admitted to the university on academic merit.[75]

In order to protect the status of the race as a competition between genuine students, the Cambridge University Blues Committee in July 2007 refused to award a blue to 2006 and 2007 Cambridge oarsman Thorsten Engelmann, as he did not complete his academic course and instead returned to the German national rowing team to prepare for the Beijing Olympics.[76] This has caused a debate about a change of rules, and one suggestion is that only students who are enrolled in courses lasting at least two years should be eligible to race.[77]

Standard of the men's crews

According to British Olympic gold medallist Martin Cross, Boat Race crews of the early 1980s were viewed as "a bit of a joke" by some international-level rowers of the time. However, their standard has improved substantially since then.[78] In 2007 Cambridge were entered in the London Head of the River Race, where they should have been measured directly against the best crews in Britain and beyond. However, the event was called off after several crews were sunk or swamped in rough conditions. Cambridge were fastest of the few crews who did complete the course.[79]

Sponsorship

Men's race

The Boat Race has been sponsored since 1976, with the money spent mainly on equipment and travel during the training period. The sponsors do not have their logos on the boats, but now tend to have their logo on kit during the race. They also provide branded training gear and have some naming rights. Boat Race sponsors have included Ladbrokes, Beefeater Gin, Aberdeen Asset Management, and the business process outsourcing company Xchanging for a few years until 2012.[80][81] Since 2010 the deal has included the crews agreeing to wear the logo on their race kit for more funding.[82] Prior to this, all sponsorship marks had been scrupulously discarded on boating for the competition, on amateurist, 'Corinthian' values but perhaps also as before televised races a single sponsor for both crews was unlikely. The sponsor has extended to being a "title sponsor" (titular, official race name) since such a longer name of the race was founded in 2010, the first three of which thus becoming The Xchanging Boat Race.[83]

In 2013, the sponsor BNY Mellon took over and it became the BNY Mellon Boat Race.[84] From 2016 to 2018, BNY Mellon and Newton Investment management donated the title sponsorship to Cancer Research UK.[85][86][87]

Women's race

The Women's Boat Race 2011 was the first to be sponsored by Newton Investment Management, a subsidiary of BNY Mellon. Previously the crews had no sponsorship and were self funded. Newton have remained the sponsor since then and increased the amount of funding significantly.[70]

The Boat Races

In 2021, the Men's and Women's Boat Races came under the same sponsorship for the first time. Gemini, a cryptocurrency exchange founded by 2010 Oxford Blues Cameron and Tyler Winklevoss, took over as title sponsor and it became the Gemini Boat Race.[citation needed]

Other boat races involving Oxford and Cambridge

Although the Boat Race crews are the best-known, the universities both field reserve crews. The reserves race takes place on the same day as the main race. The Oxford men's reserve crew is called Isis (after the Isis, a section of the River Thames which passes through Oxford), and the Cambridge reserve men's crew is called Goldie (the name comes from rower and Boat Club president John Goldie, 1849–1896, after whom the Goldie Boathouse is named). The women's reserve crews are Osiris (Oxford) and Blondie (Cambridge).[88] A veterans' boat race, usually held on a weekday before the main Boat Race, takes place on the Thames between Putney and Hammersmith.[89]

The two universities also field lightweight men's and women's crews. These squads race each other in eights as part of the Lightweight Boat Races. The first men's race took place in 1975, being joined by a women's race in 1984. Both races are currently held on the 4.2-mile (6.8 km) Championship Course from Putney to Mortlake, although they previously formed part of the Henley Boat Races, along with various other rowing races between the two universities including the openweight women's Boat Race until 2015. Competitors in the event have gone on to compete at international and Olympic levels, as well as represent their universities at openweight level.[90][91][92][93] For the men's race the average weight of the crew must be 70 kilograms (154.3 lb; 11 st 0.3 lb), with no rower weighing over 72.5 kilograms (159.8 lb; 11 st 5.8 lb). For the women's race no rower can exceed 59 kilograms (130.1 lb; 9 st 4.1 lb). At Oxford, both the men's and women's lightweight boats are awarded a full blue. At Cambridge the women's boat is awarded a full blue, whereas the men's boat receives a half-blue.[citation needed]

In popular culture

Boat race became such a popular phrase that it was incorporated into Cockney rhyming slang, for "face".[94]

In the stories of P. G. Wodehouse, several characters allude to Boat Race night as a time of riotous celebration (presumably after the victory of the character's alma mater). This frequently sees the participants in trouble with the authorities. In Piccadilly Jim, it is mentioned that Lord Datchett was thrown out of the Empire Music Hall every year on Boat Race night while he was an undergraduate.[95] Bertie Wooster mentions he is "rather apt to let myself go a bit" on Boat Race night[96] and several times describes being fined five pounds at "Bosher Street" (possibly a reference to Bow Street Magistrates' Court) for stealing a policeman's helmet one year; the beginning of the first episode of the television series Jeeves and Wooster shows his court appearance on this occasion.[97] In the short story Jeeves and the Chump Cyril, he describes having to repeatedly bail out of jail a friend who is arrested every year on Boat Race night.[98]

In Missee Lee by Arthur Ransome (one of the Swallows and Amazons series of children's books) Captain Flint (who had dropped out of Oxford) tells Missee Lee he was in gaol once on Boat-race night. High spirits. A fancy for policemen's helmets. When Missee Lee says Camblidge won and evellybody happy he replies Not that year, ma'am. We were the happy ones that year.[99] In the Jennings books by Anthony Buckeridge the protagonist's teacher Mr Wilkins is a former Cambridge rowing blue.[100]

The 1969 film The Magic Christian features the Boat Race, as Sir Guy makes use of the Oxford crew in one of his elaborate pranks.[101]

Actor and comedian Matt Berry wrote and narrated an irreverent, alternative history of the Boat Race for the BBC in 2015.[102]

Statistics

Men's race

- Number of wins: Cambridge, 87; Oxford, 81 (1 dead heat)[10]

- Most consecutive victories: Cambridge, 13 (1924–36)[10]

- Course record: Cambridge, 1998 – 16 min 19 sec; average speed 24.9 kilometres per hour (15.5 mph)[10]

- Narrowest winning margin, excluding the dead heat: 1 foot (Oxford, 2003)[10]

- Largest winning margin: 35 lengths (Cambridge, 1839)[10]

- Reserve wins: Cambridge (Goldie), 29; Oxford (Isis), 24[103]

Women's race

- Number of wins: Cambridge, 46; Oxford, 30[10]

- Course record: Cambridge, 2022 – 18 min 22 sec (faster, in different conditions, than the Cambridge men's Blue Boat in 2016 and the Oxford men's in 2014)[10][104][105]

- Reserve wins: Cambridge (Blondie), 27; Oxford (Osiris), 20[10]

Results

- Men's race

There have been 168 official races in 193 years.

| Decade | Total races | Cambridge wins | Oxford wins | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1820s | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 1830s | 2 | 2 | 0 | |

| 1840s | 7 | 5 | 2 | |

| 1850s | 6 | 2 | 4 | |

| 1860s | 10 | 1 | 9 | |

| 1870s | 10 | 7 | 2 | 1 dead heat |

| 1880s | 10 | 5 | 5 | |

| 1890s | 10 | 1 | 9 | |

| 1900s | 10 | 7 | 3 | |

| 1910s | 5 | 1 | 4 | |

| 1920s | 10 | 9 | 1 | |

| 1930s | 10 | 8 | 2 | |

| 1940s | 4 | 3 | 1 | |

| 1950s | 10 | 7 | 3 | |

| 1960s | 10 | 5 | 5 | |

| 1970s | 10 | 5 | 5 | |

| 1980s | 10 | 1 | 9 | |

| 1990s | 10 | 7 | 3 | |

| 2000s | 10 | 3 | 7 | |

| 2010s | 10 | 5 | 5 | |

| 2020s | 4 | 3 | 1 | |

| Total | 169 | 87 | 81 | 1 dead heat |

Source:[106]

- Women's race

There have been 75 races in 94 years.

See also

- Oxford–Cambridge rivalry

- The Boat Race of the North – a similar event in Northern England between Durham University and Newcastle University

- Harvard–Yale Regatta – a similar event in the United States between Harvard University and Yale University

- Scottish Boat Race – a similar event in Scotland between University of Glasgow and University of Edinburgh

- Varsity match

- The Welsh Boat Race – a similar event in Wales between Swansea University and Cardiff University

- York and Lancaster Universities Roses Race - a boat race between University of York and Lancaster University

- Great River Race - an annual 22 mile race on the River Thames between Millwall and Richmond

Notes

- ^ The 2021 Boat Race was held near Ely, Cambridgeshire, due to restrictions under Hammersmith Bridge and the COVID-19 pandemic.

References

- ^ "Partners". The Boat Race. 25 March 2021. Archived from the original on 4 April 2021. Retrieved 5 April 2021.

- ^ "Record crowd for Easter Boat Race". London Evening Standard. Archived from the original on 4 April 2010. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- ^ "Broadcast Coverage of The Gemini Boat Race". The Boat Race. Retrieved 31 March 2024.

- ^ Smith, Oliver (25 March 2014). "University Boat Race 2014: spectators' guide". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 1 July 2014. Retrieved 7 April 2014.

- ^ a b "The Boat Race origins". The Boat Race Limited. Archived from the original on 7 October 2014. Retrieved 12 October 2014.

- ^ a b Bosque, Juan Alejandro (10 June 2014). "Book of Days Tales – The Boat Race". Book of Days Tales. Archived from the original on 9 September 2014. Retrieved 12 October 2014.

- ^ "1829 Boat Race – WHERE THAMES SMOOTH WATERS GLIDE". thames.me.uk. Archived from the original on 21 October 2014. Retrieved 12 October 2014.

- ^ Quarrell, Rachel (16 March 2020). "Coronavirus forces first Boat Race cancellation outside of a world war". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 28 May 2021. Retrieved 3 September 2021.

- ^ "Boat Race cancelled because of coronavirus". BBC News. 16 March 2020. Archived from the original on 11 April 2021. Retrieved 11 April 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "The Boat Race Results". The Boat Race Limited. Archived from the original on 11 April 2012. Retrieved 13 April 2012.

- ^ a b "1877 Boat Race – WHERE THAMES SMOOTH WATERS GLIDE". thames.me.uk. Archived from the original on 21 October 2014. Retrieved 12 October 2014.

- ^ "Perfection from Torvill and Dean". ESPN. Archived from the original on 12 October 2014. Retrieved 12 October 2014.

- ^ a b "Start of the annual race". The Boat race Limited. Archived from the original on 16 October 2014. Retrieved 12 October 2014.

- ^ a b Koch, Tim (2014). "Oxford Won, Cambridge Too". Official Boat Race Programme. Archived from the original on 18 October 2014. Retrieved 12 October 2014.

- ^ "The University Boat Race". The Times. 26 March 1877. p. 8.

- ^ Daily Telegraph, 12 January, 1915, p. 8.

- ^ a b "Post war and the arrival of television". The Boat Race Limited. Archived from the original on 16 October 2014. Retrieved 12 October 2014.

- ^ Dodd, Christopher; Marks, John (2004). Battle of the Blues The Oxford & Cambridge Boat Race from 1829. P to M Limited. p. 72. ISBN 0-9547232-1-X.

- ^ Baker, Andrew (6 April 2007). "When mutineers hit the Thames". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 20 October 2014. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ a b Plummer, William (23 February 1987). "Oxford's U.S. Rowers Jump Ship, Leaving the Varsity Without All Its Oars in the Water". People. Archived from the original on 12 August 2014. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ a b c d Dodd, Christopher (July 2007). "Unnatural selection". Rowing News. pp. 54–63. Archived from the original on 12 June 2021. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ^ Roberts, Glenys (28 March 1987). "Mutiny in the boathouse". The Times. No. 62728. p. 11.

- ^ Moag, Jeff (May 2006). "Melting Pot". Rowing News. p. 40. Archived from the original on 12 June 2021. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ^ a b c Johnston, Chris (25 November 1996). "Mutiny on the Isis". Times Higher Education. Archived from the original on 12 August 2014. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ Railton, Jim (28 March 1987). "Ill wind plagues Blues of 1987". The Times. No. 62728. p. 42.

- ^ Peck, Tom (29 March 2013). "No regrets, says Trenton Oldfield, man who ruined the boat race – but don't worry, he won't be back". The Independent. Archived from the original on 20 December 2013. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- ^ "Boat Race: Man charged over swimming incident". BBC Sport. 8 April 2012. Archived from the original on 6 April 2014. Retrieved 10 April 2012.

- ^ Millar, Paul (8 April 2012). "Shock and oar as Australian protest swimmer wrecks Oxbridge boat race". Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 9 April 2012. Retrieved 10 April 2012.

- ^ Bull, Andy (7 April 2012). "Oxford bow Alex Woods recovering in hospital after Boat Race collapse". The Observer. Archived from the original on 23 October 2014. Retrieved 10 April 2012.

- ^ "Race: Royal Marines to help with security". BBC News. 9 March 2013. Archived from the original on 29 May 2017. Retrieved 1 September 2014.

- ^ "The Boat Race 2020 – cancelled". The Boat Race Company Limited. 16 March 2020. Archived from the original on 21 March 2020. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- ^ "Oxford and Cambridge Trial Eights Races". The Boat Race Company Limited. 29 December 2020. Archived from the original on 3 January 2021. Retrieved 31 December 2020.

- ^ "Boat Race: 2021 races to be moved from the Thames to Ely over safety concerns". BBC Sport. 26 November 2020. Archived from the original on 16 January 2021. Retrieved 26 November 2020.

- ^ "The Boat Race 2022 Returns to Championship Course in London". Archived from the original on 30 March 2022. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- ^ "Boat Race – WHERE THE SMOOTH WATERS GLIDE". Thames.me.uk. Archived from the original on 21 October 2014. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- ^ "Rowing back the years". BBC Sport. 31 March 2003. Archived from the original on 8 April 2014. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- ^ "Oxford University – The Boat Races". University of Oxford. Archived from the original on 14 March 2016. Retrieved 13 March 2016.

- ^ "How it began". The Race History. The Boat Race Limited. 2006. Archived from the original on 24 September 2014. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- ^ "The 10 worst mishaps in the history of sport". The Observer. 5 November 2000. Archived from the original on 28 February 2012. Retrieved 22 March 2014.

- ^ "1984: Boat race halted before starting". BBC. 17 March 2005. Archived from the original on 21 March 2012. Retrieved 10 April 2012.

- ^ "Oxford win Women's Boat Race as Cambridge struggle with sinking boat". The Guardian. Press Association. 27 March 2016. Archived from the original on 8 April 2017. Retrieved 3 September 2021.

- ^ Kingsbury, Jane; Williams, Carol (2015). Cambridge University Women's Boat Club 1941–2014 – The Struggle Against Inequality. Trireme. ISBN 9780993098291. Archived from the original on 8 April 2019. Retrieved 8 April 2019.

- ^ Morrissey, Helena (4 April 2015). "Helena Morrissey: 'Tide turns in favour of boat race women'". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 13 April 2015. Retrieved 17 April 2015.

- ^ "The real reason the women's Boat Race is closing in? Deep pockets". The Telegraph. 20 March 2015. Archived from the original on 10 April 2016. Retrieved 27 March 2016.

- ^ White, Jim; Mills, Emma; Robinson, Danielle; Saunders, Toby (5 April 2019). "Boat Race 2019: Oxford and Cambridge women admit tide has finally turned in their favour". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on 8 April 2019. Retrieved 8 April 2019.

- ^ Savva, Anna (1 December 2016). "Cambridge University set to open new boathouse in Ely". cambridgenews. Archived from the original on 8 April 2019. Retrieved 8 April 2019.

- ^ Thomas, Lauren (11 December 2016). "ROWING – Opening of the new Cambridge University Boathouse at Ely". www.sport.cam.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 8 April 2019. Retrieved 8 April 2019.

- ^ "Boat Race: 2021 races to be moved from the Thames to Ely over safety concerns". BBC Sport. 26 November 2020. Archived from the original on 16 January 2021. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- ^ "Rowing – The Boat Race". The Times. 4 March 1940. p. 8. Archived from the original on 19 June 2021. Retrieved 3 May 2015.(subscription required)

- ^ "A University Boat Race". The Times. 15 February 1943. p. 2. Archived from the original on 19 June 2021. Retrieved 2 May 2015.(subscription required)

- ^ "The Boat Race – Oxford's victory". The Times. 28 February 1944. p. 2. Archived from the original on 19 June 2021. Retrieved 2 May 2015.(subscription required)

- ^ "The Boat Race – Cambridge win". The Times. 26 February 1945. p. 2. Archived from the original on 19 June 2021. Retrieved 2 May 2015.(subscription required)

- ^ "Statistics of The Boat Race". Boat Race Company Limited. Archived from the original on 7 October 2014. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

- ^ "The Boat Race course". 28 November 2006. Archived from the original on 28 November 2006. Retrieved 10 April 2012.

- ^ "The Oxford v Cambridge Boat Race". maabc.com. Archived from the original on 24 September 2013. Retrieved 12 April 2014.

- ^ "Cambridge give Oxford the blues". BBC Sport. 2 April 1999. Archived from the original on 28 July 2003. Retrieved 6 June 2021.

- ^ a b "1943: Not a Blue Race". Hear The Boat Sing. 14 December 2014. Retrieved 13 March 2023.

- ^ "Orange Aid: The Austerity Boat Race of 1944". row2k.com. Retrieved 13 March 2023.

- ^ a b "Pulling Together". Cambridge Alumni Magazine (74 Lent 2015): 12. Archived from the original on 25 March 2015. Retrieved 19 March 2015.

- ^ Howard, Philip (13 March 1973). "Nine girls in a boat beat Oxford". The Times. p. 4.

- ^ Railton, Jim (15 March 1974). "Most exciting Boat Race for a decade". The Times. p. 13.

- ^ a b "A brief history of the Oxford-Cambridge Varsity event – from the perspective of women". The Telegraph. 13 March 2015. Archived from the original on 15 April 2015. Retrieved 11 April 2015.

- ^ "University women's race women's success". The Times. 18 March 1935. p. 6.

- ^ "History". Henley Boat Races. Archived from the original on 8 October 2014. Retrieved 15 April 2015.

- ^ "Henley Boat Races 2007". CUWBC. 2 April 2007. Archived from the original on 19 April 2015. Retrieved 18 April 2015.

- ^ "The Boat Race 2021 to be raced at Ely, Cambridgeshire". The Boat Race. 26 November 2020. Archived from the original on 21 January 2021. Retrieved 26 November 2020.

- ^ "Overview of British Film History". Learn about movie posters.com. Archived from the original on 24 October 2006. Retrieved 7 April 2007.

- ^ "Boat race viewing figures delight BBC as 4.8m watch women's event". The Guardian. 12 April 2015. Archived from the original on 29 March 2016. Retrieved 7 April 2016.

- ^ "Women's Boat Race 2015: equality will be true winner of historic meeting". The Guardian. 10 April 2015. Archived from the original on 28 March 2016. Retrieved 27 March 2016.

- ^ a b "The real reason the women's Boat Race is closing in? Deep pockets". The Telegraph. 20 March 2015. Archived from the original on 10 April 2016. Retrieved 27 March 2016.

- ^ "ITV drops Boat Race for football". BBC News. 9 December 2008. Archived from the original on 22 March 2009. Retrieved 19 August 2014.

- ^ de Rond, Mark; Redgrave, Steven. The Last Amateurs: To Hell and Back with the Cambridge Boat Race Crew. ASIN 1848310153.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "The Boat Race – Personalities". The Boat Race Company Limited. Archived from the original on 29 March 2014. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- ^ "Oxford University Sport: FAQ". University of Oxford. Archived from the original on 6 November 2014. Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- ^ "University Sports: Bursaries and Scholarships". University of Cambridge. Archived from the original on 7 October 2014. Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- ^ "Engelmann punished for early exit". BBC. 17 July 2007. Archived from the original on 3 March 2008. Retrieved 5 June 2009.

- ^ "Choppy waters ahead for Boat Race". BBC. 20 July 2007. Archived from the original on 7 March 2012. Retrieved 10 April 2012.

- ^ Cross, Martin (9 April 2012). "Rowing is elitist, but not in the way Trenton Oldfield thinks". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 11 December 2013. Retrieved 10 April 2012.

- ^ Quarrell, Rachel (1 April 2007). "Boat Race: Cambridge confidence gets big boost". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 25 May 2010.[dead link]

- ^ "Boat Race sponsor Xchanging to end contract". BBC News. 29 March 2011. Archived from the original on 23 October 2013. Retrieved 1 September 2014.

- ^ "Xchanging sponsorship of The Boat Race draws to a close". Xchanging. 29 March 2011. Archived from the original on 20 April 2011. Retrieved 1 September 2014.

- ^ Quarrell, Rachel (20 November 2009). "University Boat Race to have title sponsorship from 2010 onwards". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 5 May 2013. Retrieved 1 September 2014.

- ^ "Xchanging becomes title sponsor of The Boat Race". The Boat Race Limited. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 20 November 2009.

- ^ "Boat Race – BNY Mellon announced as new Boat Race Title Sponsor". The Boat Race Limited. 6 September 2011. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 1 September 2014.

- ^ "The Boat Races Sponsors BNY Mellon & Newton Pull Together For Cancer Research UK – The Boat Race". 19 January 2016. Archived from the original on 31 January 2016. Retrieved 19 January 2016.

- ^ Tyers, Alan (21 March 2016). "The Boat Race 2016: Cambridge win the Boat Race against Oxford but their women's boat nearly sinks". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 11 September 2017. Retrieved 3 April 2018 – via www.telegraph.co.uk.

- ^ "BNY Mellon and Cancer Research UK Boat Race sponsorship details" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 April 2016.

- ^ "The Boat Races". Cambridge University Boat Club. Archived from the original on 26 February 2021. Retrieved 3 September 2021.

- ^ "The Veterans Boat Race". The Boat Race Company Limited. 5 April 2019. Archived from the original on 28 January 2021. Retrieved 3 September 2021.

- ^ "The Other Boat Race". BBC Sport. 30 March 2010. Archived from the original on 8 May 2016. Retrieved 3 April 2016.

- ^ "CULRC". CULRC Cambridge University Lightweight Rowing Club. 20 October 2014. Archived from the original on 2 July 2017. Retrieved 27 March 2017.

- ^ "Men's Lightweight Rowing Club". Oxford University Sport. Archived from the original on 27 March 2017. Retrieved 26 March 2017.

- ^ "International Success". Oxford University Women's Lightweight Rowing Club. Archived from the original on 27 March 2017. Retrieved 26 March 2017.

- ^ Kemmer, Suzanne. "Cockney Rhyming Slang". Words in English. Archived from the original on 1 January 2018. Retrieved 19 December 2017.

- ^ Wodehouse, P. G (1918). Picadilly Jim. London: Herbert Jenkins. OCLC 1043488367. Archived from the original on 15 February 2022. Retrieved 15 February 2022.

Every one knows that young Lord Datchet was ejected from the Empire Music-Hall on Boat-Race night every year during his residence at Oxford University, but nobody minds. The family treats it as a joke.

- ^ Wodehouse, P. G. (2008) [1925]. Carry On, Jeeves (Reprinted ed.). London: Arrow Books. pp. 169–172. ISBN 978-0099513698. OCLC 819281833.

Abstemious cove though I am as a general thing, there is one night in the year when, putting all other engagements aside, I am rather apt to let myself go a bit and renew my lost youth, as it were. The night to which I allude is the one following the annual aquatic contest between the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge; or, putting it another way, Boat-Race Night. Then, if ever, you will see Bertram under the influence. And on this occasion, I freely admit, I had been doing myself rather juicily

- ^ "Jeeves Takes Charge". Jeeves and Wooster. Season 1. Episode 1. 22 April 1990. 1 minutes in.

- ^ Wodehouse, P. G. (August 1918). "Jeeves and the Chump Cyril". The Strand Magazine. 56 (312): 126–134. p. 127:

When I was up at Oxford, I used to have a regular job bailing out a pal of mine who never failed to get pinched every Boat-Race night, and he always looked like something that had been dug up by the roots.

- ^ Ransome, Arthur (2 October 2014). Missee Lee chapter 16. Random House. ISBN 9781448191079. Archived from the original on 4 April 2022. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ^ Buckeridge, Anthony (1952). Jennings and Darbyshire. Collins. Ch 24.

- ^ "The Magic Christian". Twickenham Rowing Club. Archived from the original on 17 January 2020. Retrieved 3 September 2021.

- ^ "BBC Two - Comedy Shorts, Matt Berry Does..., The Boat Race". BBC. 5 April 2015. Archived from the original on 24 February 2022. Retrieved 24 February 2022.

- ^ "The Boat Race Limited statistics". The Boat Race Limited. Archived from the original on 7 October 2014. Retrieved 1 September 2014.

- ^ "Boat Races: Oxford triumph in men's race after Cambridge women win". BBC Sport. 2 April 2017. Archived from the original on 2 April 2017. Retrieved 2 April 2017.

- ^ McLaughlin, Luke (3 April 2022). "Oxford triumph in men's Boat Race as Cambridge set record in women's event". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 3 April 2022. Retrieved 3 April 2022.

- ^ "The Boat Race yearly results – men". The Boat Race Limited. Archived from the original on 24 September 2014. Retrieved 19 August 2014.

- "Boat Race Cancelled". The Daily Telegraph. London. 2020. pp. 1–16. ISSN 0307-1235. OCLC 49632006. Retrieved 12 January 2020.