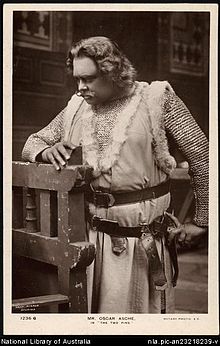

Oscar Asche

John Stange(r) Heiss Oscar Asche (24 January 1871 – 23 March 1936), better known as Oscar Asche, was an Australian actor, director, and writer, best known for having written, directed, and acted in the record-breaking musical Chu Chin Chow, both on stage and film, and for acting in, directing, or producing many Shakespeare plays and successful musicals.[1][2]

After studying acting in Norway and London, Asche made his London stage debut in 1893 and soon joined the F R Benson Company, where he remained for eight years, playing more than a hundred roles including important Shakespearean parts. He married the actress Lily Brayton in 1898, and the two were often paired onstage for many years. He played Maldonado in Arthur Wing Pinero's Iris in the West End in 1901, his first important part in modern comedy. He repeated the role on Broadway the following year, and then joined Herbert Beerbohm Tree's theatre company in London in 1902, playing more Shakespearean roles over the next few years.

Asche and his wife became managers of the Adelphi Theatre in 1904 and His Majesty's Theatre in 1907; he made his first tour of Australia in 1909–10, and was much moved by his reception in his native land. In 1911 Edward Knoblock wrote the play Kismet for him; Asche revised and shortened it, and the production enjoyed great success in London and on tour with Asche in the leading role of Hajj.

Asche most famously wrote and produced Chu Chin Chow, starring himself and his wife, which ran for an unprecedented 2,238 performances, from 31 August 1916 to 22 July 1921. During the run, among other projects, he directed the hit London production of The Maid of the Mountains. From 1922 to 1924 he toured in Australia with the J C Williamson company. As a result of his high-spending lifestyle, he was declared bankrupt in 1926. Though his success as a producer waned, he continued to direct and act, including in several films, until the mid-1930s.

Life and career

Asche was born in Geelong, Victoria, Australia. His father, Thomas, born in Norway, studied law at Christiania University; he did not pursue a legal career in Australia because he failed to master the English language.[2] After being a digger, a mounted police officer and a storekeeper, Thomas Asche became a prosperous hotel-keeper and publican in Melbourne and Sydney.[1] Asche's mother, Thomas Asche's second wife, Harriet Emma, née Trear, was born in England.[2]

Early life and training

Asche was educated at Laurel Lodge in Dandenong and the Melbourne Grammar School, which he left at 16.[3] He then went on a holiday voyage to China, and after his return to Australia was articled to an architect who died soon afterwards.[4] A few months later, he ran away and lived in the bush for some weeks and then obtained a position as a jackaroo. He returned to his parents and obtained a position in an office, but he had now decided to become an actor and made a beginning by getting up private theatricals at his home. He travelled to Fiji and on his return his father agreed to send him to Norway to study acting.[5]

At Bergen, Asche was instructed in deportment, voice production and theatre arts. He found the Norwegian acting technique to be easy and natural.[6] Two months later, he went to Christiania to study acting.[7] There he met Henrik Ibsen, who advised him to go to his own country and work in his own language.[2] Asche then went to London and was so impressed by Henry Irving and Ellen Terry in Henry VIII, that he saw the performance six times in succession. More study followed in London, where he worked to lose his Australian accent.[8] He was fortunate in having an allowance of £10 a week from his father, but could not obtain work. In December 1892 he went to Norway again to give a Shakespeare recital, which was successful and brought him a little money.

Early stage career

On 25 March 1893 Asche made his first appearance on the stage, at the Opera Comique Theatre, London, as Roberts in Man and Woman.[2] He then joined the F. R. Benson Company and for eight years gained experience an actor.[2] Among other venues, they played at the summer Stratford festivals. He started with small parts and was eventually cast as Charles the Wrestler in As You Like It, being well suited because of his excellent physique. His other early roles included Biondello in The Taming of the Shrew. He was paid a salary of £2 10s. a week, but his father had been involved in a financial crisis and was unable to send him any allowance. At holiday times when he had no salary, Asche sometimes slept on the Thames Embankment and was glad to earn trifling tips for calling cabs. His salary was raised to £4 a week, and he was never in such straits again. Asche played more than a hundred roles with Benson's company including Brutus, Claudius and other important Shakespearian parts. His resonant voice and his dignified, formal bearing are often mentioned in the reviews of his performances.[n 1] He was a good athlete and a fair cricketer. He said that he owed his place in Benson's company as much to his cricketing as to his acting abilities: the Benson company fielded a cricket team wherever it toured in the summer months.[2]

Asche married Lily Brayton, another member of the company, in 1898, and the two were often cast in the same productions for many years. In 1900 Asche appeared with the Benson Company at the Lyceum Theatre in London. Asche's biographer Richard Foulkes writes, "When Benson brought his itinerant troupe to the Lyceum Theatre in the spring of 1900 Asche appeared in six of the eight productions, most notably as Pistol, Claudius, and Thomas Mowbray, Duke of Norfolk, raising that smallish part to one of sinister grandeur."[2] Asche had another success at the Garrick Theatre in 1901 when he played Maldonado in Arthur Wing Pinero's Iris, his first important part in modern comedy.[2] Both The Times and The Observer remarked that Asche had a difficult role but carried it off.[10] He travelled to America to repeat the role on Broadway in 1902.[7] Back in London, he joined Herbert Beerbohm Tree's theatre company in 1902, and in 1903 he played Benedick in Much Ado About Nothing opposite the Beatrice of Ellen Terry.[2] Other parts were Bolingbroke in Richard II, Christopher Sly and Petruchio in The Taming of the Shrew, Bottom in A Midsummer Night's Dream, and Angelo in Measure for Measure.[7]

Actor-manager years

In 1904 Asche became co-manager with Otho Stuart of the Adelphi Theatre on a three-year lease.[11] Their productions included The Prayer of the Sword, A Midsummer Night's Dream, The Taming of the Shrew, Measure for Measure, Count Hannibal (which he wrote with F. Norreys Connell) and Rudolf Besier's The Virgin Goddess. In 1906 he played King Mark in J. Comyns Carr's play Tristram and Iseult at the Adelphi Theatre, with Lily Brayton as Iseult and Matheson Lang as Tristram.[7] In 1907 Asche and his wife took over the management of His Majesty's Theatre and produced Laurence Binyon’s Attila, with Asche in the title role, and innovative productions of Shakespeare plays, such as As You Like It, with Asche as Jacques, and Othello, with Asche in the title role. They made their first tour in Australia in 1909–10, with Asche playing Petruchio, Othello and other roles.[7] Asche was much touched by his reception at Melbourne. In his 1929 autobiography he said, "What a home-coming it was! Nothing, nothing can ever deprive me of that."[12]

On Asche's return to London in 1911, Edward Knoblock wrote the play Kismet for him, with the understanding that Asche could revise it. He shortened and partly re-wrote it and produced it with much success, playing Hajj.[13] The production ran for two years, and a successful tour in Australia followed in 1911–12, with Kismet, A Midsummer Night's Dream, and Antony and Cleopatra.[7] Back in London, Kismet was revived successfully, but in October 1914 Asche's own play Mameena based on H. Rider Haggard's novel, A Child of the Storm, though at first well received, proved a financial failure, largely on account of the conditions in London at the beginning of World War I.[14]

In 1916, Asche produced his play Chu Chin Chow, music by Frederic Norton, starring himself and his wife, which ran for 2,238 performances, from 31 August 1916 to 22 July 1921. The run easily broke the existing record of 1,466 performances, set by Charley's Aunt in the 1890s. The new record stood for decades.[15] The show drew some criticism for the ladies' scanty costumes, which Tree described as "more navel than millinery", but it was just what war-weary audiences wanted.[16] Asche played the part of Abu Hassan and confessed that "it got terribly boring going down those stairs night after night to go through the same old lines".[17] But Asche was a perfectionist, and the performance was never allowed to get slack. Chu Chin Chow also played in New York City in 1917 and Australia in 1920.[7] Asche collaborated in 1919 with Dornford Yates on a musical adaptation of Eastward Ho![18] Also during the run of Chu Chin Chow, Asche directed the hit London production of The Maid of the Mountains for Robert Evett and the George Edwardes Estate, which had an outstanding run of 1,352 performances.[15] As a director, Asche was an innovator in stage lighting and one of the first to use it as a dramatic factor in productions rather than as mere illumination. He was also known for his use of colour and his sensitivity about the dividing line between opulence and vulgarity.[citation needed]

Later years

Though Asche had been making a large income for many years, he also spent largely. He was much interested in coursing, kept many greyhounds, and lost tens of thousands of pounds gambling on them. He bought a farm in Gloucestershire that was a constant expense, and he eventually had to sell it to pay his debts.[19]

After the success of Chu Chin Chow, Asche wrote another musical that opened on Broadway in 1920 under the name Mecca and then in London the following year under the name Cairo.[7] It was not a huge success on either side of the Atlantic; in London it ran for 267 performances at His Majestys's.[20] In 1922, Asche visited Australia again, under contract to J. C. Williamson Ltd., and made successful appearances as Hornblower in John Galsworthy's The Skin Game, Maldonado in Pinero's Iris, his usual roles in Chu Chin Chow and Cairo, the title character in Julius Caesar, and in other Shakespeare plays.[2] His wife declined to join him on this tour. After disagreements with the Williamson company, his contract was abruptly terminated in June 1924.[19] On his return to Britain, as a result of excessive gambling, tax debts and unwise investments, he was declared bankrupt in 1926.[n 2]

Further successes eluded Asche as he tried to mount musicals, including The Good Old Days of England (1928), financed by his wife.[19] He continued to direct shows. His 1930 production of The Intimate Revue at the Duchess Theatre[22] was a failure. [n 3] In 1933 Asche made his last stage appearance in The Beggar’s Bowl at the Duke of York's Theatre. Asche also made appearances in seven films between 1932 and 1936, including in Two Hearts in Waltz Time (1934), as the Spirit of Christmas Present in the 1935 film Scrooge, and in The Private Secretary (1935).[24] He also wrote several books, including his autobiography, but these ventures did not solve his financial troubles.

In his final years, Asche became obese, poor, argumentative and violent. He and his wife separated, but, at the end, he returned to her and died at the age of 65 in Bisham, Berkshire, of coronary thrombosis. He was buried in the riverside cemetery there. He had no children.[2]

Writings

Asche's autobiography, Oscar Asche: His Life (1929), must be read with caution whenever figures are mentioned. He also wrote two novels: the Saga of Hans Hansen (1930), an improbable but exciting story, and The Joss Sticks of Chung (1931). His play Chu Chin Chow was published in 1931, and the vocal score of Cairo was published in 1921, but the other plays of which he was author or part author have not been printed. Among these were Mameena (1914), The Good Old Days, The Spanish Main (under the name Varco Marenes) and the libretto of Cairo.

Notes

- ^ For example, The Times described his appearance as the Prince of Morocco in The Merchant of Venice as "magnificent".[9]

- ^ Asche was discharged from bankruptcy two years later.[21]

- ^ This revue is sometimes cited as the shortest-running musical show in West End history, with less than one complete performance. The claim is not wholly correct: after a few days' additional work the revue re-opened later in March 1930. The Times remained unimpressed by the show: "The amusing hitches which varied the monotony of the first performance did not conceal the thinness of the humour and the lameness of the invention".[23]

References

- ^ a b "Oscar Asche (1871-1936)", National Library of Australia, accessed 5 April 2015

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Foulkes, Richard, "Asche, (Thomas Stange Heiss) Oscar (1871–1936)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edition, January 2011, accessed 17 April 2019 (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- ^ Asche pp. 16 and 21

- ^ Asche, p. 26

- ^ Asche, pp. 40–48

- ^ Asche, pp. 64–67

- ^ a b c d e f g h Parker, pp. 29–30

- ^ Asche, p. 72

- ^ "Comedy Theatre", The Times, 17 January 1901, p. 3

- ^ "Garrick Theatre", The Times, 23 September 1901, p. 5; and "Mr. Pinero's New Play: "Iris" at The Garrick" The Observer , 22 September 1901, p. 5

- ^ Singleton, Brian. Oscar Asche, Orientalism, and British Musical Comedy, Praeger Publishing (2004), p. 49

- ^ Asche, p. 126

- ^ Kismet in The Play Pictorial Vol. XVIII, No. 106 (1911), accessed at the Stagebeauty website on 22 December 2009

- ^ Asche, p. 159

- ^ a b Gaye, p. 1525

- ^ "Oscar Asche 1871–1936", Liveperformance.com.au, 2007, accessed 8 February 2018

- ^ Asche, p. 166

- ^ "Theatres", The Times, 10 September 1919, p. 8

- ^ a b c Blake, L. J., "Asche, Thomas Stange Heiss Oscar (1871–1936)", Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University , accessed 5 April 2013

- ^ Gaye, p. 1529

- ^ "Mr. Oscar Asche's Affairs", The Times, 5 April 1928, p. 4

- ^ "Entertainments" The Times, 27 February 1930, p. 12

- ^ "Duchess Theatre", The Times, 31 March 1930, p. 12

- ^ "Oscar Asche", British Film Institute, accessed 5 March 2013

Sources

- Asche, Oscar (1929). Oscar Asche, his life: by himself. London: Hurst & Blackett. OCLC 1968577.

- Gaye, Freda, ed. (1967). Who's Who in the Theatre (fourteenth ed.). London: Sir Isaac Pitman and Sons. OCLC 5997224.

- Parker, John (1925). Who's Who in the Theatre (fifth ed.). London: Sir Isaac Pitman and Sons. OCLC 10013159.

External links

- Works by or about Oscar Asche at the Internet Archive

- Oscar Asche and Lily Brayton Collection, in the Performing Arts Collection, at Arts Centre Melbourne.

- "Oscar Asche" biography at the Australian Variety Theatre Archive

- Oscar Asche's profile at the Emory University Shakespeare Project

- List of some of Asche's performances in Australia (AusStage)

- Oscar Asche at the Internet Broadway Database

- Biography, bibliography, Australian tour information and resource listing for Oscar Asche in the National Library of Australia

- Picture Australia records of images of Oscar Asche

- Oscar Asche at IMDb