Internet traffic

Internet traffic is the flow of data within the entire Internet, or in certain network links of its constituent networks. Common traffic measurements are total volume, in units of multiples of the byte, or as transmission rates in bytes per certain time units.

As the topology of the Internet is not hierarchical, no single point of measurement is possible for total Internet traffic. Traffic data may be obtained from the Tier 1 network providers' peering points for indications of volume and growth. However, Such data excludes traffic that remains within a single service provider's network and traffic that crosses private peering points.

As of December 2022 almost half (48%) of mobile Internet traffic is in India and China, while North America and Europe have about a quarter.[1] However, mobile traffic remains a minority of total internet traffic.

Traffic sources

File sharing constitutes a fraction of Internet traffic.[2] The prevalent technology for file sharing is the BitTorrent protocol, which is a peer-to-peer (P2P) system mediated through indexing sites that provide resource directories. According to a Sandvine Research in 2013, Bit Torrent’s share of Internet traffic decreased by 20% to 7.4% overall, reduced from 31% in 2008. [3]

As of 2023, roughly 65% of all internet traffic came from video sites,[4] up from 51% in 2016.[5]

Traffic management

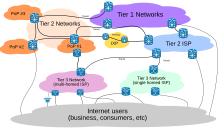

Internet traffic management, also known as application traffic management. The Internet does not employ any formally centralized facilities for traffic management. Its progenitor networks, especially the ARPANET established an early backbone infrastructure which carried traffic between major interchange centers for traffic, resulting in a tiered, hierarchical system of internet service providers (ISPs) within which the tier 1 networks provided traffic exchange through settlement-free peering and routing of traffic to lower-level tiers of ISPs. The dynamic growth of the worldwide network resulted in everмНФа-increasing interconnections at all peering levels of the Internet, so a robust system was developed that could mediate link failures, bottlenecks, and other congestion at many levels.[citation needed]

Economic traffic management (ETM) is the term that is sometimes used to point out the opportunities for seeding as a practice that caters to contribution within peer-to-peer file sharing and the distribution of content in the digital world in general. [6]

Internet use tax

A planned tax on Internet use in Hungary introduced a 150-forint (US$0.62, €0.47) tax per gigabyte of data traffic, in a move intended to reduce Internet traffic and also assist companies to offset corporate income tax against the new levy.[7] Hungary achieved 1.15 billion gigabytes in 2013 and another 18 million gigabytes accumulated by mobile devices. This would have resulted in extra revenue of 175 billion forints under the new tax based on the consultancy firm eNet.[7]

According to Yahoo News, economy minister Mihály Varga defended the move saying "the tax was fair as it reflected a shift by consumers to the Internet away from phone lines" and that "150 forints on each transferred gigabyte of data – was needed to plug holes in the 2015 budget of one of the EU’s most indebted nations".[8]

Some people argue that the new plan on Internet tax would prove disadvantageous to the country’s economic development, limit access to information and hinder the freedom of expression.[9] Approximately 36,000 people have signed up to take part in an event on Facebook to be held outside the Economy Ministry to protest against the possible tax.[8]

In 1998, the United States enacted the Internet Tax Freedom Act (ITFA) to prevent the imposition of direct taxes on internet usage and online activities such as emails, internet access, bit tax, and bandwidth tax.[10][11] Initially, this law placed a 10-year moratorium on such taxes, which was later extended multiple times and made permanent in 2016. The ITFA's goal was to protect consumers and support the growth of internet traffic by prohibiting recurring and discriminatory taxes that could hinder internet adoption and usage. As a result, ITFA has played a crucial role in promoting the digital economy and safeguarding consumer interests. According to Pew Research Center, as of 2024, approximately 93% of Americans use the internet, with platforms like YouTube and Facebook being highly popular.[12][13][14][15] Additionally, 90% of U.S. households subscribed to high-speed internet services by 2021.[16][17] Although the ITFA provides protection against direct internet taxes, ongoing debates about internet regulation and governance continue to shape the landscape of internet traffic and usage in the United States.

Traffic classification

Traffic classification describes the methods of classifying traffic by observing features passively in the traffic and line with particular classification goals. There might be some that only have a vulgar classification goal. For example, whether it is bulk transfer, peer-to-peer file-sharing, or transaction-orientated. Some others will set a finer-grained classification goal, for instance, the exact number of applications represented by the traffic. Traffic features included port number, application payload, temporal, packet size, and the characteristic of the traffic. There is a vast range of methods to allocate Internet traffic including exact traffic, for instance, port (computer networking) number, payload, heuristic, or statistical machine learning.

Accurate network traffic classification is elementary to quite a few Internet activities, from security monitoring to accounting and from the quality of service to providing operators with useful forecasts for long-term provisioning. Yet, classification schemes are extremely complex to operate accurately due to the shortage of available knowledge of the network. For example, the packet header-related information is always insufficient to allow for a precise methodology.

Bayesian analysis techniques

Work[18] involving supervised machine learning to classify network traffic. Data are hand-classified (based upon flow content) to one of a number of categories. A combination of data set (hand-assigned) category and descriptions of the classified flows (such as flow length, port numbers, time between consecutive flows) are used to train the classifier. To give a better insight of the technique itself, initial assumptions are made as well as applying two other techniques in reality. One is to improve the quality and separation of the input of information leading to an increase in accuracy of the Naive Bayes classifier technique.

The basis of categorizing work is to classify the type of Internet traffic; this is done by putting common groups of applications into different categories, e.g., "normal" versus "malicious", or more complex definitions, e.g., the identification of specific applications or specific Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) implementations.[19] Adapted from Logg et al.[20]

Survey

Traffic classification is a major component of automated intrusion detection systems.[21][22] They are used to identify patterns as well as an indication of network resources for priority customers, or to identify customer use of network resources that in some way contravenes the operator’s terms of service. Generally deployed Internet Protocol (IP) traffic classification techniques are based approximately on a direct inspection of each packet’s contents at some point on the network. Source address, port and destination address are included in successive IP packets with similar if not the same 5-tuple of protocol type. ort are considered to belong to a flow whose controlling application we wish to determine. Simple classification infers the controlling application’s identity by assuming that most applications consistently use well-known TCP or UDP port numbers. Even though, many candidates are increasingly using unpredictable port numbers. As a result, more sophisticated classification techniques infer application types by looking for application-specific data within the TCP or User Datagram Protocol (UDP) payloads.[23]

Global Internet traffic

Aggregating from multiple sources and applying usage and bitrate assumptions, Cisco, a major network systems company, has published the following historical Internet Protocol (IP) and Internet traffic figures:[24]

| Year |

IP traffic (PB/month) |

Fixed Internet traffic (PB/month) |

Mobile Internet traffic (PB/month) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 | 0.001 | 0.001 | n/a |

| 1991 | 0.002 | 0.002 | n/a |

| 1992 | 0.005 | 0.004 | n/a |

| 1993 | 0.01 | 0.01 | n/a |

| 1994 | 0.02 | 0.02 | n/a |

| 1995 | 0.18 | 0.17 | n/a |

| 1996 | 1.9 | 1.8 | n/a |

| 1997 | 5.4 | 5.0 | n/a |

| 1998 | 12 | 11 | n/a |

| 1999 | 28 | 26 | n/a |

| 2000 | 84 | 75 | n/a |

| 2001 | 197 | 175 | n/a |

| 2002 | 405 | 356 | n/a |

| 2003 | 784 | 681 | n/a |

| 2004 | 1,477 | 1,267 | n/a |

| 2005 | 2,426 | 2,055 | 0.9 |

| 2006 | 3,992 | 3,339 | 4 |

| 2007 | 6,430 | 5,219 | 15 |

| 2008 [25] | 10,174 | 8,140 | 33 |

| 2009 [26] | 14,686 | 10,942 | 91 |

| 2010 [27] | 20,151 | 14,955 | 237 |

| 2011 [28] | 30,734 | 23,288 | 597 |

| 2012 [29][30] | 43,570 | 31,339 | 885 |

| 2013 [31] | 51,168 | 34,952 | 1,480 |

| 2014 [32] | 59,848 | 39,909 | 2,514 |

| 2015 [33] | 72,521 | 49,494 | 3,685 |

| 2016 [34] | 96,054 | 65,942 | 7,201 |

| 2017 [35] | 122,000 | 85,000 | 12,000 |

"Fixed Internet traffic" refers perhaps to traffic from residential and commercial subscribers to ISPs, cable companies, and other service providers. "Mobile Internet traffic" refers perhaps to backhaul traffic from cellphone towers and providers. The overall "Internet traffic" figures, which can be 30% higher than the sum of the other two, perhaps factors in traffic in the core of the national backbone, whereas the other figures seem to be derived principally from the network periphery.

Cisco also publishes 5-year projections.

| Year |

Fixed Internet traffic (EB/month) |

Mobile Internet traffic (EB/month) |

|---|---|---|

| 2018 | 107 | 19 |

| 2019 | 137 | 29 |

| 2020 | 174 | 41 |

| 2021 | 219 | 57 |

| 2022 | 273 | 77 |

Internet backbone traffic in the United States

The following data for the Internet backbone in the US comes from the Minnesota Internet Traffic Studies (MINTS):[36]

| Year | Data (TB/month) |

|---|---|

| 1990 | 1 |

| 1991 | 2 |

| 1992 | 4 |

| 1993 | 8 |

| 1994 | 16 |

| 1995 | n/a |

| 1996 | 1,500 |

| 1997 | 2,500–4,000 |

| 1998 | 5,000–8,000 |

| 1999 | 10,000–16,000 |

| 2000 | 20,000–35,000 |

| 2001 | 40,000–70,000 |

| 2002 | 80,000–140,000 |

| 2003 | n/a |

| 2004 | n/a |

| 2005 | n/a |

| 2006 | 450,000–800,000 |

| 2007 | 750,000–1,250,000 |

| 2008 | 1,200,000–1,800,000 |

| 2009 | 1,900,000–2,400,000 |

| 2010 | 2,600,000–3,100,000 |

| 2011 | 3,400,000–4,100,000 |

The Cisco data can be seven times higher than the Minnesota Internet Traffic Studies (MINTS) data not only because the Cisco figures are estimates for the global—not just the domestic US—Internet, but also because Cisco counts "general IP traffic (thus including closed networks that are not truly part of the Internet, but use IP, the Internet Protocol, such as the IPTV services of various telecom firms)".[37] The MINTS estimate of US national backbone traffic for 2004, which may be interpolated as 200 petabytes/month, is a plausible three-fold multiple of the traffic of the US's largest backbone carrier, Level(3) Inc., which claims an average traffic level of 60 petabytes/month.[38]

Edholm's law

In the past Internet bandwidth in telecommunications networks doubled every 18 months, an observation expressed as Edholm's law.[39] This follows the advances in semiconductor technology, such as metal-oxide-silicon (MOS) scaling, exemplified by the MOSFET transistor, which has shown similar scaling described by Moore's law. In the 1980s, fiber-optical technology using laser light as information carriers accelerated the transmission speed and bandwidth of telecommunication circuits. This has led to the bandwidths of communication networks achieving terabit per second transmission speeds.[40]

See also

References

- ^ Kar, Ayushi (2022-12-04). "End of American internet, India-China contribute to 50% of world's data traffic". www.thehindubusinessline.com. Retrieved 2022-12-24.

- ^ "Data volume of global file sharing traffic from 2013 until 2018". Statista. 2014. Retrieved 18 October 2014.

- ^ Paul Resenikoff (12 November 2013). "File-Sharing Now Accounts for Less Than 10% of US Internet Traffic..." Retrieved 18 October 2014.

- ^ "In 2022, 65% of all internet traffic came from video sites". 20 January 2023.

- ^ "An explosion of online video could triple bandwidth consumption again in the next five years". 8 June 2017.

- ^ Despotovic, Z., Hossfeld, T., Kellerer, W., Lehrieder, F., Oechsner, S., Michel, M. (2011). Mitigating Unfairness In Locality-Aware Peer-To-Peer Networks. International Journal of Network Management

- ^ a b Marton Dunai (2014). "Hungary plans new tax on Internet traffic, public calls for rally". Archived from the original on December 20, 2015.

- ^ a b "Anger mounts in Hungary over internet tax". Yahoo News. 25 October 2014. Retrieved 18 October 2014.

- ^ Margit Feher (2014). "Public outrage mounts against hunger's plan to tax internet use". Retrieved 18 October 2014.

- ^ "The Internet Tax Freedom Act: In Brief" (PDF). FAS Project on Government Secrecy. Retrieved 2024-10-26.

- ^ "- INTERNET TAX ISSUES". www.govinfo.gov. Retrieved 2024-10-26.

- ^ Gottfried, Jeffrey (2024-01-31). "Americans' Social Media Use". Pew Research Center. Retrieved 2024-10-26.

- ^ "Internet, Broadband Fact Sheet". Pew Research Center. 2024-01-31. Retrieved 2024-10-26.

- ^ Jeffrey, Gottfried (2024-01-31). "traffic user". Pew Research Center. Retrieved 2024-10-26.

- ^ "Social Media Fact Sheet". Pew Research Center. 2024-01-31. Retrieved 2024-10-26.

- ^ "92 Percent of U.S. Households Get an Internet Service at Home". Benton Foundation. 2023-12-11. Retrieved 2024-10-26.

- ^ Buckley, Sean (2023-12-20). "LRG: 92% of households can get residential internet service". Lightwave. Retrieved 2024-10-26.

- ^ Denis Zuev (2013). "Internet traffic classification using bayesian analysis technique" (PDF). Retrieved 18 October 2014.

- ^ J.Padhye; S.Floyd (June 2001). "Identifying the TCP Behavior of Web Servers". In Proceedings of SIGCOMM 2011, San Diego, CA.

- ^ C.Logg; L.Cottrell (2003). "SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory". Archived from the original on June 13, 2008. Retrieved 21 October 2014.

- ^ Bro intrusion detection system – Bro overview, http://bro-ids.org, as of August 14, 2007.

- ^ V. Paxson, ‘Bro: A system for detecting network intruders in real-time,’ Computer Networks, no.31 (23-24), pp. 2435-2463, 1999

- ^ S. Sen., O. Spats check, and D. Wang, ‘Accurate, scalable in network identification of P2P traffic using application signatures,’ in WWW2004, New York, NY, USA, May 2004.

- ^ "Visual Networking Index", Cisco Systems

- ^ Cisco, "Cisco Visual Networking Index: Forecast and Methodology, 2008–2013" (PDF), 9 June 2009. Retrieved 13 June 2016

- ^ Cisco, "Cisco Visual Networking Index: Forecast and Methodology, 2009–2014" (PDF), 2 June 2010. Retrieved 13 June 2016

- ^ Cisco, "Cisco Visual Networking Index: Forecast and Methodology, 2010–2015" (PDF), 1 June 2011. Retrieved 13 June 2016

- ^ Cisco, "Cisco Visual Networking Index: Forecast and Methodology, 2011–2016 Archived 2020-08-09 at the Wayback Machine" (PDF), 30 May 2012. Retrieved 13 June 2016

- ^ Cisco, "Cisco Visual Networking Index: Global Mobile Data Traffic Forecast Update, 2012–2017 Archived 2016-08-12 at the Wayback Machine" (PDF), 2 Feb 2013. Retrieved 13 June 2016

- ^ Cisco, "Cisco Visual Networking Index: Forecast and Methodology, 2012–2017" (PDF), 29 May 2013. Retrieved from archive.org, 28 Aug 2016

- ^ Cisco, "Cisco Visual Networking Index: Forecast and Methodology, 2013–2018" (PDF), 10 Jun 2014. Retrieved from archive.org, 28 Aug 2016

- ^ Cisco, "Cisco Visual Networking Index: Forecast and Methodology, 2014–2019" (PDF), 27 May 2015. Retrieved from archive.org, 28 Aug 2016

- ^ Cisco, "Cisco Visual Networking Index:Forecast and Methodology, 2015–2020" (PDF) 6 June 2016. Retrieved 13 June 2016

- ^ Cisco, "Cisco Visual Networking Index:Forecast and Methodology, 2016–2021" (PDF) 6 June 2017. Retrieved 14 August 2017

- ^ a b Cisco, "Cisco Visual Networking Index:Forecast and Trends, 2017–2022" (PDF) 28 November 2018. Retrieved 9 January 2019

- ^ Minnesota Internet Traffic Studies (MINTS) Archived 2017-12-28 at the Wayback Machine, University of Minnesota

- ^ "MINTS - Minnesota Internet Traffic Studies". Retrieved 16 April 2017.

- ^ 2004 Annual Report, Level(3), April 2005, p.1

- ^ Cherry, Steven (2004). "Edholm's law of bandwidth". IEEE Spectrum. 41 (7): 58–60. doi:10.1109/MSPEC.2004.1309810. S2CID 27580722.

- ^ Jindal, R. P. (2009). "From millibits to terabits per second and beyond - over 60 years of innovation". 2009 2nd International Workshop on Electron Devices and Semiconductor Technology. pp. 1–6. doi:10.1109/EDST.2009.5166093. ISBN 978-1-4244-3831-0. S2CID 25112828.

Further reading

- Williamson, Carey (2001). "Internet Traffic Measurement". IEEE Internet Computing. 5 (6): 70–74. doi:10.1109/4236.968834.

External links

- "The Size and Growth Rate of the Internet", K.G. Coffman and Andrew Odlyzki, First Monday, Volume 3, Number 5, October 1998

- Internet Traffic Report from AnalogX

- Internet Health Report from Keynote Systems

- Cooperative Association for Internet Data Analysis Archived 2014-05-14 at the Wayback Machine (CAIDA), based at the University of California, San Diego Supercomputer Center