Anglo-Saxon royal genealogies

A number of royal genealogies of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, collectively referred to as the Anglo-Saxon royal genealogies, have been preserved in a manuscript tradition based in the 8th to 10th centuries.

The genealogies trace the succession of the early Anglo-Saxon kings, back to the semi-legendary kings of the Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain, notably named as Hengist and Horsa in Bede's Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum, and further to legendary kings and heroes of the pre-migration period, usually including an eponymous ancestor of the respective lineage and converging on Woden. In their fully elaborated forms as preserved in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles and the Textus Roffensis, they continue the pedigrees back to the biblical patriarchs Noah and Adam. They also served as the basis for pedigrees that would be developed in 13th century Iceland for the Scandinavian royalty.

Documentary tradition

The Anglo-Saxons, uniquely among the early Germanic peoples, preserved royal genealogies.[1] The earliest source for these genealogies is Bede, who in his Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum (completed in or before 731[2]) said of the founders of the Kingdom of Kent:

The two first commanders are said to have been Hengest and Horsa ... They were the sons of Victgilsus, whose father was Vecta, son of Woden; from whose stock the royal race of many provinces deduce their original.[3]

Bede similarly provides ancestry for the kings of the East Angles.[4]

An Anglian collection of royal genealogies also survives, the earliest version (sometimes called Vespasian or simply V) containing a list of bishops that ends in the year 812. This collection provides pedigrees for the kings of Deira, Bernicia, Mercia, Lindsey, Kent and East Anglia, tracing each of these dynasties from Woden, who is made the son of an otherwise unknown Frealaf.[5] The same pedigrees, in both text and tabular form, are included in some copies of the Historia Brittonum, an older body of tradition compiled or significantly retouched by Nennius in the early 9th century. These apparently share a common late-8th century source with the Anglian collection.[6] Two other manuscripts from the 10th century (called CCCC and Tiberius, or simply C and T) also preserve the Anglian collection, but include an addition: a pedigree for King Ine of Wessex that traces his ancestry from Cerdic, the semi-legendary founder of the Wessex state, and hence from Woden.[7] This addition probably reflects the growing influence of Wessex under Ecgbert, whose family claimed descent from a brother of Ine.[8]

Pedigrees are also preserved in several regnal lists dating from the reign of Æthelwulf and later but seemingly based on a late-8th or early 9th century source or sources.[9] Finally, later interpolations (which were added by 892) to both Asser's Vita Ælfredi regis Angul Saxonum and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle preserve Wessex pedigrees extended beyond Cerdic and Woden to Adam.[10]

John of Worcester would copy these pedigrees into his Chronicon ex chronicis, and the 9th-century Anglo-Saxon genealogical tradition also served as a source for the Icelandic Langfeðgatal and was used by Snorri Sturluson for his 13th century Prologue to the Prose Edda.

Euhemerism

The majority of the surviving pedigrees trace the families of Anglo-Saxon royalty to Woden. The euhemerizing treatment of Woden as the common ancestor of the royal houses is presumably a "late innovation" within the genealogical tradition which developed in the wake of the Christianization of the Anglo-Saxons. Kenneth Sisam has argued that the Wessex pedigree was co-opted from that of Bernicia, and David Dumville has reached a similar conclusion with regard to that of Kent, deriving it from the pedigree of the kings of Deira.

When looking at pedigree sources outside of the Anglian collection, one surviving pedigree for the kings of Essex in a similar fashion traces the family from Seaxneat. In later pedigrees, this too has been linked to Wōden by making Seaxnēat his son. Dumville has suggested that these modified pedigrees linking to Wōden were creations intended to express their contemporary politics, a representation in genealogical form of the Anglian hegemony over all the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms.

The derivation of a claim of kingship from descent from a god may be rooted in ancient Germanic paganism. In Anglo-Saxon England after Christianization, this tradition appears to have been euhemerized to kingship of any of the realms of the Heptarchy being conditional on descent from Woden.[11]

Woden is made father of Wecta, Beldeg, Wihtgils and Wihtlaeg[12] who are given as ancestors of the Kings of Kent, Deira, Wessex, Bernicia, Mercia and East Anglia, as well as the independent founder turned son, Seaxnēat, the Essex ancestor. These lineages having thus been made to converge, the portion of the pedigree before Woden was then subjected to several successive rounds of extension, and also the interpolation of mythical heroes and other modifications, producing a final genealogy that traced to the Biblical patriarchs and Adam.[13]

Kent and Deira

Bede relates that Hengest and Horsa, semi-legendary founders of the Kentish royal family, were sons of Wihtgils (Victgilsi), [son of Witta (Vitti)], son of Wecta (Vecta), son of Woden. Witta is omitted from some manuscripts, but his name appears as part of the same pedigree repeated in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle and Historia Brittonum. The Anglian Collection gives a similar pedigree for Hengest, with Wecta appearing as Wægdæg, and the names Witta and Wihtgils exchanging places, with a similar pedigree being given by Snorri Sturluson in his much later Prologue to the Prose Edda, where Wægdæg, called Vegdagr son of Óðinn, is made a ruler in East Saxony. Grimm suggested that a shared first element of these names Wicg-, representing Old Saxon wigg and Old Norse vigg, and reflects, like the names Hengest and Horsa, the horse totem of the Kentish dynasty.[14] From Hengest's son Eoric, called Oisc, comes the name of the dynasty, the Oiscingas, and he is followed as king by Octa, Eormenric, and the well-documented Æthelberht of Kent. The Anglian Collection places Octa (as Ocga) before Oisc (Oese).

The genealogy given for the kings of Deira in both the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle and the Anglian Collection also traces through Wægdæg, followed by Siggar and Swæbdæg. The Prose Edda also gives these names, as Sigarr and Svebdeg alias Svipdagr, but places them a generation farther down the Kent pedigree, as son and grandson of Wihtgils. Though Sisam rejected the linguistic identity of Bede's Wecta with Wægdæg, the Anglian Collection and Prose Edda place Wægdæg in the ancestry of both lines and Dumville suggests this common pedigree origin reflected the political alliance of Kent with Deira coincident with the marriage of Edwin of Deira with Æthelburh of Kent, which appears to have led to the grafting of the unrelated Jutish Kent dynasty onto a Deira pedigree belonging to an Anglian body of genealogical tradition.[15] Historia Brittonum connects the Deira line to a different branch of Woden's descendants, showing Siggar to be son of Brond, son of Beldeg, a different son of Woden. This matches the lineage atop the Bernicia pedigree in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle and that of Wessex in the Anglian Collection. The transfer of the Deira line from kinship with Kent royal line to that of Bernicia was perhaps meant to mirror the political union that joined Deira and Bernicia into the kingdom of Northumbria.

| Kent | Deira | Bernicia | |||||

| Bede | Anglian Collection |

Prose Edda | Anglo-Saxon Chronicle B,C |

Anglian Collection |

Historia Brittonum |

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle | |

| Woden | Woden | Óðinn | Woden | Woden | Woden | Woden | |

| Wecta | Wægdæg | Vegdagr | Wægdæg | Wægdæg | Beldeg | Bældæg | |

| Witta | Wihtgils | Vitrgils | Brond | Brand | |||

| Wihtgils | Witta | Vitta[a] | Sigarr | Sigegar | Siggar | Siggar | Benoc |

| Hengest | Hengest | Heingest | Svebdeg/Svipdagr | Swebdæg | Swæbdæg | Aloc | |

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, Anglian Collection and Historia Brittonum all give descent from Siggar/Sigegar to Ælla, the first historically-documented king of Deira, and the latter's son Edwin, who first joined Deira with neighboring Bernicia into what would become the Kingdom of Northumbria, an accomplishment Historia Brittonum attributes to his ancestor Soemil. While clearly sharing a common root, the three pedigrees differ somewhat in the precise details. The Chronicle pedigree apparently dropped a generation. That of Historia Brittonum has two differences. It lacks two early generations, a likely scribal error that resulted from a jump between the similar names Siggar and Siggeot, a similar gap appearing in the later pedigree given by chronicler Henry of Huntingdon, whose Historia Anglorum otherwise faithfully follows the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle pedigree, but here jumps directly from 'Sigegeat' to Siggar's father, Wepdeg (Wægdæg). There is also a substitution later in the pedigree, where Historia Brittonum replaces the name Westorfalcna with Sguerthing, apparently the Swerting of Beowulf, although its -ing ending led John of Worcester, writing in the 12th century Chronicon ex chronicis, to interpret the name as an Anglo-Saxon patronymic and interpose the name Swerta as Seomil's father into a pedigree otherwise matching that of the Anglian Collection.[16] The replaced name, Wester-falcna (west falcon) along with the earlier Sæ-fugel (sea-fowl), were seen by Grimm as totemic bird names analogous to the horse names in the Kent pedigree.[17]

| Anglo-Saxon Chronicle B,C |

Historia Anglorum |

Anglian Collection |

Historia Brittonum |

Chronicon ex chronicis |

| Sigegar | Sigegeat | Siggar | Siggar | Siggar |

| Swebdæg | Swæbdæg | Swæbdæg | ||

| Siggeāt | Siggeot | Siggæt | ||

| Sǣbald | Seabald | Sæbald | Sibald | Sæbald |

| Sǣfugel | Sefugil | Sæfugol | Zegulf | Sæfugol |

| Swerta | ||||

| Soemel | Soemil | Soemel | ||

| Westerfalca | Westrefalcna | Westorualcna | Sguerthing | Westorwalcna |

| Wilgils | Wilgils | Wilgils | Guilglis | Wilgels |

| Uxfrea | Uscfrea | Uscfrea | Ulfrea | Wyscfrea |

| Yffe | Iffa | Yffe | Iffi | Yffe |

| Ælle | Ella | Ælle | Ulli | Ealle |

Mercia

The pedigree given the kings of Mercia traces their family from Wihtlæg, who is made son (Anglo-Saxon Chronicle), grandson (Anglian collection) or great-grandson (Historia Brittonum) of Woden. His descendants are frequently viewed as legendary Kings of the Angles, but as Wiglek, he is transformed into a king of Denmark, the rival of Amleth (Hamlet), in the 12th century Gesta Danorum ("deeds of the Danes") of Saxo Grammaticus, perhaps as a fusion bringing together the Mercian Wihtlæg with the Wiglaf of Beowulf.[18] The next two generations of the Mercian pedigree, Wermund and Uffa, are likewise made Danish rulers by Saxo, as does his contemporary Sven Aggesen's Brevis Historia Regum Dacie, Wermund here being son of king Froði hin Frökni. The second of these, Uffa, as Offa of Angel, is known independently from Beowulf, Widsith and Vitae duorum Offarum ("The lives of the two Offas"). At this point the Danish pedigrees diverge from the Anglo-Saxon tradition, making him father of Danish king Dan. Beowulf makes Offa father of Eomer, while in the Anglo-Saxon genealogies he is Eomer's grandfather, via an intermediate named Angeltheow, Angelgeot, or perhaps Ongengeat (the Origon of Historia Brittonum being an apparent misreading of Ongon-[19]). Eliason has suggested that this insertion derives from a byname of Eomer, according to Beowulf the son of a marriage between an Angel and a Geat,[20] but the name may represent an attempt to interpolate the heroic Swedish king Ongenþeow who appears independently in Beowulf and Widsith and in turn is sometimes linked with the earliest historical Danish king, Ongendus, named in Alcuin's 8th-century Vita Willibrordi archiepiscopi Traiectensis. Eomer, Offa's son or grandson, is then made father of Icel, the legendary eponymous ancestor of the Icling dynasty that founded the Mercian state, except in the surviving version of Historia Brittonum, which skips over not only Icel but Cnebba, Cynwald, and Creoda, jumping straight to Pybba, whose son Penda is the first documented as king, and who along with his 12 brothers gave rise to multiple lines that would succeed to the throne of Mercia through the end of the 8th century.

| Anglo-Saxon Chronicle |

Anglian Collection |

Historia Brittonum |

Chronicon ex chronicis |

Beowulf | Gesta Danorum |

Brevis Historia Regum Dacie |

| Woden | Woden | Woden | Woden | |||

| Wihtlæg | Weoðolgeot | Guedolgeat | Withelgeat | |||

| Gueagon | Waga | |||||

| Wihtlæg | Guithlig | Wihtleag | Wiglek | Froði hin Frökni | ||

| Wærmund | Wærmund | Guerdmund | Weremund | Garmund | Wermund | Wermund |

| Offa | Offa | Ossa | Offa | Offa | Uffa | Uffa |

| Angeltheow | Angelgeot | Origon | Angengeat | Dan | Dan | |

| Eomær | Eomer | Eamer | Eomer | Eomer | ||

| Icel | Icel | Icel |

East Anglia

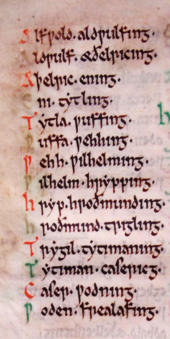

The ruling dynasty of East Anglia, the Wuffingas, were named for Wuffa, son of Wehha, who is made the ancestor of the historical Wuffingas dynasty, and given a pedigree from Woden.[21] Wehha appears as Ƿehh Ƿilhelming (Wehha Wilhelming - son of Wilhelm) in the Anglian Collection.[22] According to the 9th-century History of the Britons, his father Guillem Guercha (the Wilhelm of the Anglian Collection pedigree) was the first king of the East Angles,[23] but D. P. Kirby is among those historians who have concluded that Wehha was the founder of the Wuffingas line.[24] From Wilhelm the pedigree is continued back through Hryþ, Hroðmund (a name otherwise only known from Beowulf[citation needed]), Trygil, Tyttman, Caser (Latin Caesar, i.e. Julius Caesar) to Woden. The placement of Caesar within this pedigree perhaps defers to early traditions deriving Woden from 'Greekland'.[25] The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle gives no pedigree for this dynasty.

| Cronicon ex Cronicis |

Anglian Collection |

Historia Brittonum |

| Woden | Woden | Woden |

| Caser | Caser | Casser |

| Titmon | Tẏtiman | Titinon |

| Trigils | Trẏgil | Trigil |

| Rothmund | Hroðmund | Rodnum |

| Hripp | Hrẏp | Kypp |

| Wihelm | Ƿilhelm | Guithelm |

| Ƿehh | Gueca | |

| Vffa/Wffa | Ƿuffa | Guffa |

Wessex and Bernicia

While excluded from the original pedigree sources, two later copies of the Anglian collection from the 10th century (called CCCC and Tiberius, or simply C and T) include an addition: a pedigree for King Ine of Wessex that traces his ancestry from Cerdic, the semi-legendary founder of the Wessex state, and hence from Woden.[7] This addition probably reflects the growing influence of Wessex under Ecgbert, whose family claimed descent from a brother of Ine.[8] This Anglian king-list seems to have been a source for the West Saxon Genealogical Regnal List, an early version of which was itself a source for the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle but which took its surviving form during the reigns of Æthelwulf or his sons.[9][26] Finally, later interpolations (which were added by 892) to both Asser's Vita Ælfredi regis Angul Saxonum and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle preserve Wessex pedigrees extended beyond Cerdic and Woden to Adam.[10] Scholars have long noted discrepancies in the Wessex pedigree tradition. The pedigree as it appears in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is at odds with the earlier Anglian collection in that it contains four additional generations and consists of doublets which when expressed with patronymics would have resulted in the uniform triple alliteration that is common in Anglo-Saxon poetry, but that would have been difficult for a family to maintain over a number of generations and is unlike known Anglo-Saxon naming practices.[27][28]

| Anglian Collection C&T | West Saxon Genealogical Regnal List | Anglo Saxon Chronicle |

| Woden | Woden | Woden |

| Bældæg | Bældæg | Bældæg |

| Brand | Brond | Brond |

| Freoðogar | Friðgar | |

| Freawine | Freawine | |

| Wig | Wig | |

| Giwis | Giwis | Giwis |

| Esla | ||

| Aluca | Elesa | Elesa |

| Cerdic | Cerdic | Cerdic |

Further, when comparing the Chronicle's pedigrees of Cerdic and of Ida of Bernicia several anomalies are evident. While the two peoples had no tradition of common origin, their pedigrees share the generations immediately after Woden, Bældæg whom Snorri equated with the God Baldr, and Brand. One might expect Cerdic to be given descent from a different son of Woden, if not from a different god entirely such as the Saxon patron, Seaxnēat, who once headed the pedigree of the Essex kings before his relegation as another son of Woden. Likewise, while the Chronicle places Ida's reign after Cerdic's death, the pedigrees do not reflect this difference in age.[29][30]

| Wessex | Bernicia |

| Woden | |

| Bældæg | |

| Brond/Brand | |

| Friðgar | Benoc |

| Freawine | Aloc |

| Wig | Angenwit |

| Giwis | Ingui |

| Esla | Esa |

| Elesa | Eoppa |

| Cerdic | Ida |

The name Cerdic, moreover, may actually be an Anglicized form of the Brythonic name Ceredic and several of his successors also have names of possible Brythonic origin, indicating that the Wessex founders may not have been Germanic at all.[31] All of these suggest that the pedigree may not be authentic.

Sisam hypothesis

| Asser (original) |

Sisam hypothetical intermediate |

Anglo Saxon Chronicle |

| UUoden | Woden | Woden |

| Belde(g) | Bældæg | Bældæg |

| Brond | Brond | Brond |

| Friðgar | ||

| Freawine | Freawine | |

| Wig | Wig | |

| Geuuis | Giwis | Giwis |

| Esla | ||

| Elesa | Elesa | Elesa |

| Cerdic | Cerdic | Cerdic |

The Wessex royal pedigree continued to puzzle historians until, in 1953, Anglo-Saxon scholar Kenneth Sisam presented an analysis that has since been almost universally accepted by historians. He noted similarities between the earlier versions of the Wessex pedigree and that of Ida. Those appearing in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle and in the published transcript of Asser (the original having been lost in an 18th-century fire) are in agreement, but several earlier manuscript transcripts of Asser's work give, instead, the shorter pedigree of the later Anglian collection manuscripts, probably representing the original text of Asser and the earliest form of the Cerdic pedigree.[32] Sisam speculated that the additional names arose through the insertion of a pair of Saxon heroes, Freawine and Wig, into the existing pedigree, creating a second alliterative pair (after Brand/Bældæg, Giwis/Wig, where the stress of "Giwis" is on the second syllable) and inviting further alliteration, the addition of Esla to complete an Elesa/Esla pair, and of Friðgar to make a Freawine/Friðgar alliteration.[33] Of these alliterative names (in a culture whose poetry depended upon alliteration rather than rhyme) only Esla is perhaps known elsewhere: British historians working before Sisam suggested that his name is that of Ansila, a legendary Goth ancestor or that he is Osla 'Bigknife' of Arthurian legend,[34] an equivalency still followed by some Arthurian writers, although Osla is elsewhere identified with Octa of Kent.[35] Elesa has also been linked to the Romano-Briton Elasius, the "chief of the region" met by Germanus of Auxerre.[36]

Having concluded that the shorter form of the royal genealogy was the original, Sisam compared the names found in different versions of the Wessex and Northumbrian royal pedigrees, revealing a similarity between the Bernician pedigree found in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle and those given for Cerdic: rather than diverging several generations earlier they are seen to correspond until the generation immediately before Cerdic, with the exception of one substitution. "Giwis", seemingly a supposed eponymous ancestor of the Gewisse (a name given to the early West Saxons) appears instead of a similarly eponymous ancestor of the Bernicians (Old English, Beornice), Benoc in the Chronicle and (slightly rearranged in order) Beornic or Beornuc in other versions. This suggests that the Bernician pedigree was co-opted in a truncated form by Wessex historians, replacing one "founding father" with another.[37][38][39]

| Ida of Bernicia | Cerdic of Wessex | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anglian Collection V | Historia Brittonum | Anglo Saxon Chronicle | Anglian Collection C&T | Asser (original text) | Anglo Saxon Chronicle (without additions) |

| Uoden | Woden | Woden | Woden | UUoden | Woden |

| Beldæg | Beldeg | Bældæg | Bældæg | Belde(g) | Bældæg |

| Beornic | Beornuc | Brand | Brand | Brond | Brond |

| Wegbrand | Gechbrond | ||||

| Ingibrand | Benoc | Giwis | Geuuis | Giwis | |

| Alusa | Aluson | Aloc | Aluca | Elesa | Elesa |

| Angengeot | Inguec | Angenwit | Cerdic | Cerdic | Cerdic |

| : : |

: : |

: : |

|||

| Ida | Ida | Ida | |||

Sisam concluded that at one time the Wessex royal pedigree went no earlier than Cerdic and that it was subsequently elaborated by borrowing the Bernician royal pedigree that went back to Woden, introducing the heroes Freawine and Wig and inserting additional names to provide alliterative couplets.[37] Dumville concurred with this conclusion, and suggested that the Wessex pedigree was linked to that of Bernicia to reflect a 7th-century political alliance.[40]

Bernicia pedigree

Ida is given as the first king of Bernicia. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle indicates that Ida's reign began in 547, and records him as the son of Eoppa, grandson of Esa, and great-grandson of Ingui.[41] Likewise, the Historia Brittonum records him as the son of Eoppa, and calls him the first king of Berneich or Bernicia, but inserts an additional generation between Ida and its Ingui equivalent, Inguec, while the Anglian collection moves its version of this man several generations before, in the combined name form Ingibrand.[42] Richard North suggests that the presence of this Ing- individual among the ancestors of Ida in the Bernician pedigree relates to the Ingvaeones in Germania, referring to the seaboard tribes among which were the Angles who would later found Bernicia. He hypothesizes that Ingui, representing the same Germanic god as the Norse Yngvi, originally was held to be founder of the Anglian royal families at a time predating the addition of the eponymous Beornuc and extension of the pedigree to Woden. The name Brand/Brond also appears at different positions in the pedigree, either as the entire name or part of a combined name, with Gech-/Weg- and Ingi- elements.[38] One name, Angengeot/Angenwit, appearing in two of the Bernicia pedigrees also is present in that of Mercia. The name may have been added to reflect a political alliance between the two kingdoms.[43]

| Anglian Collection V | Historia Brittonum | Anglo Saxon Chronicle |

| Uoden | Woden | Woden |

| Beldæg | Beldeg | Bældæg |

| Brand | ||

| Beornic | Beornuc | Benoc |

| Wegbrand | Gechbrond | |

| Ingibrand | ||

| Alusa | Aluson | Aloc |

| Angengeot | Angenwit | |

| Inguec | Ingui | |

| Eðilberht | Aedibrith | Esa |

| Oesa | Ossa | |

| Eoppa | Eobba | Eoppa |

| Ida | Ida | Ida |

Northumbria arose from the union of Bernicia with the kingdom of Deira under Ida's grandson Æthelfrith. The genealogies of the Anglo-Saxon kings attached to some manuscripts of the Historia Brittonum give more information on Ida and his family; the text names Ida's "one queen" as Bearnoch and indicates that he had twelve sons. Several of these are named, and some of them are listed as kings.[44] One of them, Theodric, is noted for fighting against a British coalition led by Urien Rheged and his sons.[45] Some 18th- and 19th-century commentators, beginning with Lewis Morris, associated Ida with the figure of Welsh tradition known as Flamdwyn ("Flame-bearer").[46] This Flamdwyn was evidently an Anglo-Saxon leader opposed by Urien Rheged and his children, particularly his son Owain, who slew him.[47] However, Rachel Bromwich notes that such an identification has little to back it;[47] other writers, such as Thomas Stephens and William Forbes Skene, identify Flamdwyn instead with Ida's son Theodric, noting the passages in the genealogies discussing Theodric's battles with Urien and his sons.[46] Ida's successor is given as Glappa, one of his sons, followed by Adda, Æthelric, Theodric, Frithuwald, Hussa, and finally Æthelfrith (d. c. 616), the first Northumbrian monarch known to Bede.

Lindsey

| Anglian Collection |

|---|

| Uuoden |

| Uinta |

| Cretta |

| Cueldgils |

| Cædbæd |

| Bubba |

| Beda |

| Biscop |

| Eanferð |

| Eatta |

| Aldfrið |

A genealogy for Lindsey is also part of the collection. However, unlike the other kingdoms, the lack of surviving chronicle materials covering Lindsey deprive its pedigree of context. In his analysis of the pedigree, Frank Stenton pointed to three names as being informative. Cædbæd includes the British element cad-, indicative of interaction between the two cultures in the early days of settlement. A second name, Biscop, is the Anglo-Saxon word for bishop, and suggests a time after conversion. Finally, Alfreið, the king to whom the document traces, is not definitively known elsewhere, but Stenton suggested identification with an Ealdfrid rex who witnessed a confirmation by Offa of Mercia.[48] However, Ealdfrid rex is now interpreted to be an error for Offa's son Ecgfrið rex, anointed as King of Mercia during his father's lifetime, rather than the Lindsey ruler. Grimm sees in the Biscop Bedecing of the pedigree the same name form as that of the "Biscop Baducing" appearing in Vita Sancti Wilfrithi.[49]

Essex

For the southern realm of the East Saxons, a unique pedigree is preserved that does not derive the royal family from Wōden. This pedigree is thought to be independent of the Anglian collection, and ends with Seaxnēat ("companion of the Saxons", or simply knife-companion), matching the Saxnôt whom, along with Wodan and Thunaer, ninth-century Saxon converts to Christianity were made explicitly to renounce. Subsequently, Seaxnēat was turned into an additional son of Wōden, connecting the Essex royal pedigree to the others of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms. The first king, Æscwine of Essex, is placed seven generations below Seaxnēat in the pedigree.

Ancestry of Woden

The earliest surviving manuscript that extends prior to Woden, the Vespasian version of the Anglian collection, only gives one additional name, that of Woden's father, an otherwise unknown Frealeaf. However, in the case of the genealogy of the kings of Lindsey, it makes Frealeaf son of Friothulf, son of Finn, son of Godwulf, son of Geat. This appears to be a more recent addition, added after the Historia Brittonum tabular genealogies were derived from the Anglian collection's precursor, and subsequently added to other lineages.[50]

In the prose pedigree of Hengist in Historia Brittonum, Godwulf, father of Finn, was replaced by a variant of Folcwald the father of legendary Frisian hero Finn known from Beowulf and the Finnesburg Fragment.[51] Later versions do not follow this change: some add an additional name, making Friothwald the father of Woden, while others omit Friothulf.[52] Grimm compares the various versions of the pedigree immediately prior to Woden and concludes that the original version was likely most similar to that of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, with Woden son of Fridho-wald, son of Fridho-lâf, son of Fridho-wulf.[53]

The name at the head of this pedigree is that of another legendary Scandinavian, Geat, apparently the eponymous ancestor of the Geats and perhaps once a god.[54] This individual has also been taken as corresponding to Gapt, the head of the genealogy of the Goths as given by Jordanes.[b]

None of the individuals between Woden and Geat, except possibly Finn, is known elsewhere. Sisam concludes, "Few will dissent from the general opinion that the ancestors of Woden were a fanciful development of Christian times."[56]

| Bede | Anglian Collection V all but Lindsey |

Anglian Collection V Lindsey |

Historia Brittonum Hengest Pedigree |

Anglo Saxon Chronicle Abington 547 annal |

Anglo Saxon Chronicle Otho B 547 annal |

Anglo Saxon Chronicle Parker 855 annal, Asser, Æthelweard |

Anglo Saxon Chronicle Abington & others 855 annal Anglian Collection T |

Langfeðgatal | Prose Edda Snorri Sturluson |

| Geat | Guta | Geat | Geat | Geat | Geat | Eat | Ját | ||

| Godwulf | Folcpald | Godwulf | Godwulf | Godwulf | Godwulf | Godvlfi | Guðólfr | ||

| Finn | Fran | Finn | Finn | Finn | Finn | Finn | Finn | ||

| Frioþulf | Freudulf | Friþulf | Friþuwulf | Friþuwulf | |||||

| Frealeaf | Frealeaf | Frelaf | Freoþelaf | Frealeaf | Frealeaf | Frealaf | Fríallaf | ||

| Friþuwald | Friðleif | ||||||||

| Woden | Woden | Woden | Uuoden | Woden | Woden | Woden | Woden | Voden/Oden | Vóden/Óðin |

Several medieval sources extend the pedigree prior to Geat to the legendary Scandinavian heroes Skjöldr and Sceafa. These fall into three classes, the shortest being found in the Latin translation of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle prepared by Æthelweard, himself a descendant of the royal family. His version makes Geat the son of Tetuua, son of Beow, son of Scyld, son of Scef.[57] The last three generations also appear in Beowulf in the pedigree of Hroðgar, but with the name of Beow expanded to that of the poem's hero.[58]

The surviving manuscripts of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle instead place several generations between Scyld and Sceaf. Asser gives a similar pedigree with some different name forms and one version of the Chronicle has an obvious error removing the early part of the pedigree, but all these clearly represent a second pedigree tradition.[59]

One of the later surviving manuscripts of the Anglian collection has dropped two of the names from this descent and this identifies it or a related manuscript as the source for the version of the pedigree that appears in the Icelandic Langfeðgatal and in Snorri's Prose Edda pedigree.[60]

The Chronicle and Anglian collection versions appear to have had additional names interpolated into the older tradition reported by Æthelweard, one of them, Heremod, reflecting the legendary ruler of the Danish Scyldings.[61]

William of Malmesbury's Gesta Regum Anglorum presents a third variant that tries to harmonize the two alternatives. Sceaf appears twice, once as father of Scyld as in the Æthelweard and Beowulf pedigrees, then again as Streph, father of Bedwig atop the longer lineage of the Chronicle and Anglian collection.[62]

| Beowulf | Æthelweard | Anglo-Saxon Chronicle |

Anglian Collection T |

Langfeðgatal | Prose Edda | Gesta Regum Anglorum[c] |

| Scēf | Scef | Sceaf | Scef | Seskef/ Sescef |

Seskef | Streph |

| Bedwig | Bedwig | Bedvig | Bedvig | Bedweg | ||

| Hwala | Gwala | |||||

| Haðra | Haðra | Athra | Athra | Hadra | ||

| Itermon | Iterman | Itermann | Ítermann | Stermon | ||

| Heremod | Heremod | Heremotr | Heremód | Heremod | ||

| Sceaf | ||||||

| Scyld | Scyld | Scyldwa | Skealdwa | Skealdna | Skjaldun | Sceld |

| Bēowulf | Beo | Beaw | Beaw | Beaf | Bjáf | Beow |

| Healfdene | Tetuua | Tætwa | Tet | |||

| Hrōðgār | Geat | Geat(a) | Eat | Eat | Ját | Get |

The earliest names in the constructed pedigree, the connection to the Biblical genealogy, were the last to be added. Noah has been made father, or via Shem, grandfather of Sceaf and traced back to Adam, an extension not followed by Æthelweard who apparently used a copy of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle containing that extension, but also had family material independent of the Chronicle.[63]

The Langfeðgatal, which co-opts the Anglo-Saxon pedigree to provide ancestry for the Scandinavian royal dynasties, continues the process of pedigree elongation. From the Anglian collection (T) manuscript or a source closely related to it Langfeðgatal has taken the names from Woden to Scef, called Sescef or Seskef (from Se Scef wæs Noes sunu - "this Scef was Noah's son" in the T pedigree).[60] Then rather than placing Noah immediately before Sceaf, a long line of names known from Norse and Greek mythology, although not bearing their traditional familial relationships, is added. Sceaf's ancestry is traced through Magi (Magni), Móda (Móði, both Magni and Móði being sons of Thor), Vingener, Vingeþor, Einriði and Hloriþa (all four being names of Thor) to "Tror, whom we call Thor", with Thor being made son of king Memnon by Tróan, daughter of Priam of Troy.

Priam is then given a pedigree of classical Greek ancestors, including Jupiter and Saturn, that connects to the Biblical Book of Nations via the branch shared by the Greeks. This derives the line from Japheth, Noah's son who by medieval tradition was ancestor of all European peoples.[64]

See also

Notes

- ^ Different published editions and transcriptions of Snorri's genealogy show the father of Heingest as Ritta, Pitta or Picta, but the initial letter likely was originally a wynn - /Ƿ/, represents the modern /w/. Grimm (1888), p. 1727 does not hesitate in identifying the name given by Snorri with Bede's Witta, and this order of names matches that of the Anglian Collection.

- ^ "The genealogies do not end with Woden but go back to a point five generations earlier, the full list of names in the earlier genealogies being Frealaf—Frithuwulf—Finn—Godwulf—Geat. Of the first four of these persons nothing is known. Asser says that Geat was worshipped as a god by the heathen, but this statement is possibly due to a passage in Sedulius' Carmen Paschale which he has misunderstood and incorporated in his text. It has been thought by many modern writers that the name is identical with Gapt which stands at the head of the Gothic genealogy in Jordanes, cap. 14; but the identification is attended with a good deal of difficulty."[55]

- ^ Latin -ius' endings have been removed

References

- ^ Sisam, p. 287

- ^ J. Robert Wright (2008). A Companion to Bede: A Reader's Commentary on the Ecclesiastical History of the English People. William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. p. 2. ISBN 978-0802863096.

- ^ Bede, Ecclesiastical History of the English Nation, Chapter XV. From the Internet Medieval Sourcebook. Other manuscripts include an additional generation, making Vitgilsi son of Vitta, son of Vecta, son of Voden.

- ^ Sisam, pp. 288

- ^ Sisam, pp. 287-290

- ^ Sisam, pp. 292-294

- ^ a b Sisam, pp. 290-292

- ^ a b Sisam, p. 291

- ^ a b Sisam, pp. 294-297

- ^ a b Sisam, pp. 297-298

- ^ N.J. Higham (2002). King Arthur: Myth-Making and History. Routledge. p. 100]. ISBN 978-0415483988.. "no king by the late seventh century could do without the status that descent from Woden entailed." Richard North (1998). Heathen Gods in Old English Literature. Cambridge University Press. p. 13. ISBN 978-0521551830.

- ^ The Anglo-Saxon chronicle. Translated by Swanton, Michael James. Routledge. 1998 [1996]. pp. 2, 16, 18, 24, 50, 66. ISBN 978-0415921299.

- ^ Sisam, pp. 322-331

- ^ Grimm (1888), pp. 1712-1713.

- ^ Dumville (1977), p. 79.

- ^ Haigh (1872), p. 37. Haigh attributes this pedigree to "Florence of Worcester", formerly thought to have written the majority of Chronicon ex chronicis.

- ^ Grimm (1888), p. 1717.

- ^ Malone, Kemp (1964) [1923]. The Literary History of Hamlet: The Early Tradition. Haskell House. pp. 245–. LCCN 65-15886. GGKEY:05LP22FA23F. Retrieved 6 December 2012.

- ^ Grimm (1888), pp. 1715-1716.

- ^ Norman E. Eliason, "The 'Thryth-Offa Digression' in Beowulf", in Franciplegius: Medieval and Linguistic Studies in Honor of Francis Peabody Magoun, Jr., New York: New York University Press, 1965, pp. 124-138

- ^ Newton, The Origins of Beowulf , p. 105.

- ^ Medway Council, Medway City Ark: Textus Roffensis, notes. Accessed 9 August 2010.

- ^ Nennius, History of the Britons, p. 412.

- ^ Kirby, The Earliest English Kings, p. 15.

- ^ Grimm (1888), p. 1714.

- ^ David N. Dumville, 'The West Saxon Genealogical Regnal List and the Chronology of Early Wessex', Peritia, 4 (1985), 21–66 (esp. pp. 59–60).

- ^ R. W. Chambers, Beowulf, an Introduction, Cambridge: University Press, 1921, p. 316

- ^ Sisam, pp. 298,300-307

- ^ Sisam, pp. 300-304

- ^ Richard North, Heathen Gods in Old English Literature, Cambridge: University Press, 1997, p. 43

- ^ David Parsons, "British *Caratīcos, Old English Cerdic", Cambridge Medieval Celtic Studies, vol. 33, pp. 1-8 (1997); Henry Howorth, "The Beginnings of Wessex", The English Historical Review, vol. 13, pp. 667-71 (1898) - a contrary opinion is taken by Alfred Anscombe, "The Name of Cerdic", Y Cymmrodor: The Magazine of the Honorable Society of Cymmrodorion vol. 29, pp. 151-209 (1919)

- ^ Sisam, pp. 300-305

- ^ Sisam, pp. 304-307

- ^ Alfred Anscombe, "The Date of the First Settlement of the Saxons in Britain: II. Computation in the Eras of the Passion and the Incarnation 'secundum Evangelicam Veritatem'", Zeitschrift für Celtische Philologie, vol. 6, pp. 339-394 at p. 369; Alfred Anscombe, "The Name of Cerdic", Y Cymmrodor: The Magazine of the Honorable Society of Cymmrodorion vol. 29, pp. 151-209 (1919) at p. 179.

- ^ Mike Ashley, The Mammoth Book of King Arthur, p. 211; Evans, John H., "The Arthurian Campaign", Archaeologia Cantiana, 78: 83–95, at. p. 85

- ^ Grosjean, P., Analecta Bollandiana, 1957. Hagiographie Celtique pp. 158-226.

- ^ a b Sisam, pp. 305-307

- ^ a b North, p. 43

- ^ Dumville, 1977, p. 80

- ^ Dumville, 1977, pp. 80-1.

- ^ The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, entry for 547.

- ^ Historia Brittonum, ch. 56.

- ^ Newton, p. 68

- ^ Historia Brittonum, ch. 57.

- ^ Historia Brittonum, ch. 63.

- ^ a b Morris-Jones, John (1918). "Taliesin". Y Cymmrodor. 28: 154.

- ^ a b Bromwich, Rachel (2006). Trioedd Ynys Prydein: The Triads of the Island of Britain. University of Wales Press. ISBN 978-0-7083-1386-2., p. 353.

- ^ Stenton, F. M. (Frank Merry), "Lindsey and its Kings", Essays presented to Reginald Lane Poole, 1927, pp. 136-150, reprinted in Preparatory to Anglo-Saxon England: Being the Collected Papers of Frank Merry Stenton : Edited by Doris Mary Stenton, Oxford, 1970, pp. 127-137 [1]

- ^ Grimm (1888), p. 1719.

- ^ Sisam, pp. 308-9

- ^ Sisam, pp. 309-10

- ^ Sisam, pp. 310-14

- ^ Grimm (1888), p. 1722.

- ^ Sisam, pp. 307-8

- ^ Chadwick, Hector Munro. The Origin of the English Nation (1907) (Page 270)

- ^ Sisam, pp. 308

- ^ Sisam, pp. 314, 317-318

- ^ Murray; Sam Newton, The Origins of Beowulf and the Pre-Viking Kingdom of East Anglia, pp. 54-76.

- ^ Sisam, pp. 313-6

- ^ a b Chambers, p. 313

- ^ Sisam, pp. 318

- ^ Sisam, pp. 318-320

- ^ Sisam, 320-322; Daniel Anlezark, "Japheth and the origins of the Anglo-Saxons", Anglo Saxon England, vol. 31, pp. 13-46.

- ^ Bruce, pp. 56–60

Sources

- Bruce, Alexander M., Scyld and Scef: Expanding the Analogues, London, Routledge, 2002 (https://books.google.com/books?id=hDFIeCj0xasC at Google Books)

- Chambers, R. W., Beowulf, an Introduction to the Study of the Poem with a Discussion of the Stories of Offa and Finn, Cambridge: University Press, 1921

- Dumville, David, "Kingship, Genealogies and Regnal Lists", in Early Medieval Kingship, P.W. Sawyer and Ian N. Wood, eds., Leeds University, 1977, pp. 72–104

- Dumville, David "The Anglian collection of royal genealogies and regnal lists", in Anglo-Saxon England, Clemoes, ed., 5 (1976), pp. 23–50.

- Grimm, Jacob (1888). Teutonic Mythologies. Vol. IV (Appendix I: Anglo-Saxon Genealogies). Translated by Stallybrass, James Steven. London: George Bell. pp. 1709–1736.

- Haigh, Daniel Henry (1872), "On the Jute, Angle, and Saxon royal pedigrees", Archaeologia Cantiana, 8: 18–49

- Kirby, D. P. (2000) [1991]. The earliest English kings (revised ed.). Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-24210-3.

- Moisl, Hermann, "Anglo-Saxon royal genealogies and Germanic oral tradition", Journal of Medieval History, 7:3 (1981), pp. 215–48. doi:10.1016/0304-4181(81)90002-6

- Murray, Alexander Callander, "Beowulf, the Danish invasion, and royal genealogy", The Dating of Beowulf, Colin Chase, ed. University of Toronto Center for Medieval Studies, 1997, pp. 101–111.

- Newton, Sam, The Origin of Beowulf and the Pre-Viking Kingdom of East Anglia, Rochester, NY, Boydell & Brewer, 1993.

- North, Richard, Heathen Gods in Old English Literature, Cambridge: University Press, 1997

- Sisam, Kenneth (1953). "Anglo-Saxon Royal Genealogies". Proceedings of the British Academy. 39: 287–348. (reprinted as Sisam, Kenneth (1990). "Anglo-Saxon Genealogies". In Stanley, E. G. (ed.). British Academy Papers on Anglo-Saxon England. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 145–204. ISBN 0197260845.)

- Giles, J. A.; Ingram, J. (1847). The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle – via at Project Gutenberg.