Homeland

| Part of a series on |

| Nationalism |

|---|

| Part of a series on |

| Conservatism |

|---|

|

A homeland is a place where a national or ethnic identity has formed. The definition can also mean simply one's country of birth.[1] When used as a proper noun, the Homeland, as well as its equivalents in other languages, often has ethnic nationalist connotations. A homeland may also be referred to as a fatherland, a motherland, or a mother country, depending on the culture and language of the nationality in question.

Motherland

Motherland refers to a mother country, i.e. the place in which somebody grew up or had lived for a long enough period that somebody has formed their own cultural identity, the place that one's ancestors lived for generations, or the place that somebody regards as home, or a Metropole in contrast to its colonies. People often refer to Mother Russia as a personification of the Russian nation. The Philippines is also considered as a motherland which is derived from the word "Inang Bayan" which means "Motherland". Within the British Empire, many natives in the colonies came to think of Britain as the mother country of one, large nation. India is often personified as Bharat Mata (Mother India). The French commonly refer to France as "la mère patrie";[2] Hispanic countries that were former Spanish colonies commonly referred to Spain as "la Madre Patria". Romans and the subjects of Rome saw Italy as the motherland (patria or terrarum parens) of the Roman Empire, in contrast to Roman provinces.[3][4] Turks refer to Turkey as "ana vatan" (lit: mother homeland.). Kathleen Ni Houlihan is a mythical symbol of Irish nationalism found in literature and art including work by W.B. Yeats and Seán O'Casey, She was an emblem during colonial rule, and became associated with the Irish Republican Army in Northern Ireland, especially during The Troubles.

Fatherland

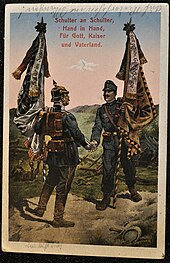

Fatherland is the nation of one's "fathers", "forefathers", or ancestors. The word can also mean the country of nationality, the country in which somebody grew up, the country that somebody's ancestors lived in for generations, or the country that somebody regards as home, depending on how the individual uses it.[5] It can be viewed as a nationalist concept, in so far as it is evocative of emotions related to family ties and links them to national identity and patriotism. It can be compared to motherland and homeland, and some languages will use more than one of these terms.[6]

The Ancient Greek patris, fatherland, led to patrios, of our fathers and thence to the Latin patriota and Old French patriote, meaning compatriot; from these the English word patriotism is derived. The related Ancient Roman word Patria led to similar forms in modern Romance languages.

The term fatherland is used throughout Europe where a Germanic language is spoken. In Dutch vaderland is used in the national anthem, "Het Wilhelmus", which lyrics are written around 1570. It is also common to refer to the national history as vaderlandse geschiedenis.

In German, the term Vaterland became more prominent in the 19th century. It appears in numerous patriotic songs and poems, such as Hoffmann's song Lied der Deutschen which became the national anthem in 1922. German government propaganda used its appeal to nationalism when making references to Germany and the state.[7][8] It was used in Mein Kampf,[9] and on a sign in a German concentration camp, also signed, Adolf Hitler.[10]

Because of the use of Vaterland in Nazi-German war propaganda, the term "Fatherland" in English has become associated with domestic British and American anti-Nazi propaganda during World War II. This is not the case in Germany itself, or in other Germanic speaking and Eastern European countries, where the word remains used in the usual patriotic contexts.

Terms equating "Fatherland" in Germanic languages:

- Afrikaans: Vaderland

- Danish: fædreland

- Dutch (Flemish): vaderland[11]

- West Frisian: heitelân

- German: Vaterland[12] (as in the national anthem Das Lied der Deutschen, also Austrians, the Swiss as in the national anthem Swiss Psalm and Liechtensteiners)

- Icelandic: föðurland

- Norwegian: fedreland

- Scots: faitherland

- Swedish: fäderneslandet (besides the more common fosterlandet; the word faderlandet also exists in Swedish but is never used for Sweden itself, but for other countries such as Germany).

A corresponding term is often used in Slavic languages, in:

- Russian otechestvo (отечество) or otchizna (отчизна)

- Polish ojczyzna in common language literally meaning "fatherland", ziemia ojców literally meaning "land of fathers",[13] sometimes used in the phrase ziemia ojców naszych[14] literally meaning "land of our fathers" (besides rarer name macierz "motherland")

- Ukrainian batʹkivshchyna (батьківщина) or vitchyzna (вітчизна).

- Czech otčina (although the normal Czech term for "homeland" is vlast)

- the Belarusians as Бацькаўшчына (Baćkaŭščyna)

- Serbo-Croatian otadžbina (отаџбина) meaning "fatherland", domovina (домовина) meaning "homeland", dedovina (дедовина) or djedovina meaning "grandfatherland" or "land of grandfathers"

- Bulgarian татковина (tatkovina) as well as otechestvo (Отечество)

- Macedonian татковина (tatkovina)

Other groups that refer to their native country as a "fatherland"

Groups with languages that refer to their native country as a "fatherland" include:

- the Arabs as أرض الآباء 'arḍ al-'abā' ("land of the fathers")

- the Albanians as Atdhe

- the Amharas as አባት አገር (Abbat Ager)

- the Rohingya as Bafodinná woton

- the Arakaneses as A pha rakhaing pray (အဖရခိုင်ပြည်)

- the Chechens as Daimokh

- the Estonians as isamaa (as in the national anthem Mu isamaa, mu õnn ja rõõm)

- the Finns as isänmaa

- the Georgians as Samshoblo (სამშობლო - "[land] of parents") or Mamuli (მამული)

- the Ancient Greeks as πατρίς patris

- the Italians as padreterra

- the Greeks as πατρίδα patrida'

- the Kazakhs as atameken

- the Kyrgyz as ata meken

- the Latvians as tēvzeme

- the Lithuanians as tėvynė

- the Nigerians as fatherland

- the Oromo as Biyya Abaa

- the Pakistanis as Vatan (madar-e-watan means motherland. Not fatherland)

- the Somali as Dhulka Abaa, land of the father

- the Thais as pituphum (ปิตุภูมิ), the word is adapted from Sanskrit

- the Tibetans as ཕ་ཡུལ (pha yul)

- the Welsh as Hen Wlad Fy Nhadau, 'the ancient land of my fathers'

Romance languages

In Romance languages, a common way to refer to one's home country is Patria/Pátria/Patrie which has the same connotation as Fatherland, that is, the nation of our parents/fathers (From the Latin, Pater, father). As patria has feminine gender, it is usually used in expressions related to one's mother, as in Italian la Madrepatria, Spanish la Madre Patria or Portuguese a Pátria Mãe (Mother Fatherland). Examples include:

- the Esperantists as patrio, patrolando or patrujo

- Aragonese, Asturian, Franco-Provençal, Galician, Italian, Spanish (in its many dialects): Patria

- Catalan: Pàtria

- Occitans: Patrìo

- French: Patrie

- Romanian: Patrie

- Portuguese: Pátria

Multiple references to parental forms

- the Armenians, as Hayrenik (Հայրենիք), home. The national anthem Mer Hayrenik translates as Our Fatherland

- the Azerbaijanis as Ana vətən (lit. mother homeland; vətən from Arabic) or Ata ocağı (lit. father's hearth)

- the Bosniaks as Otadžbina (Отаџбина), although Domovina (Домовина) is sometimes used colloquially meaning homeland

- the Chinese as zǔguó (祖国 or 祖國 (traditional chinese), "land of ancestors"), zǔguómǔqīn (祖国母亲 or 祖國母親, "ancestral land, the mother") is frequently used.

- the Czechs as vlast, power or (rarely) otčina, fatherland

- the Hungarians as szülőföld (literally: "bearing land" or "parental land")

- the Indians as मातृभूमि literally meaning "motherland", or पितृभूमि translating to "fatherland" in the Indo-Aryan liturgical tradition

- the Kurds as warê bav û kalan meaning "land of the fathers and the grandfathers"

- the Japanese as sokoku (祖国, "land of ancestors")

- the Koreans as joguk (조국, Hanja: 祖國, "land of ancestors")

- French speakers: Patrie, although they also use la mère patrie, which includes the idea of motherland

- the Latvians as tēvija or tēvzeme (although dzimtene – roughly translated as "place that somebody grew up" – is more neutral and used more commonly nowadays)

- the Burmese as အမိမြေ (ami-myay) literally meaning "motherland"

- the Persians as Sarzamin e Pedari (Fatherland), Sarzamin e Mādari (Motherland) or Mihan (Home)

- the Poles as ojczyzna (ojczyzna is derived from ojciec, Polish for father, but ojczyzna itself and Polska are feminine, so it can also be translated as motherland), also an archaism macierz "mother" is rarely used.

- the Russians, as Otechestvo (отечество) or Otchizna (отчизна), both words derived from отец, Russian for father. Otechestvo is neuter, otchizna is feminine.

- the Slovenes as očetnjava, although domovina (homeland) is more common.

- the Swedes as fäderneslandet, although fosterlandet is more common (meaning the land that fostered/raised a person)

- the Vietnamese as Tổ quốc (Chữ Nôm: 祖國, "land of ancestors")

In Hebrew

Jews, especially Modern-Day Israelis, use several different terms, all referring to Israel, including:

- Moledet (מולדת; Birth Land). The most analogous Hebrew word to the English term 'Homeland'.

- Erets Israel (ארץ ישראל; Land of Israel). This is the most common usage.

- Haarets (הארץ; The Land). This is used by Israelis, and Jews abroad, when making distinctions between Israel and other countries in conversation.

- Haarets Hamuvtachat (הארץ המובטחת; The Promised Land). This is a term with historical and religious connotations.

- Erets Zion (ארץ ציון; Land of Zion; Land of Jerusalem). Notably use in The Israeli Anthem.

- Erets Avot (ארץ אבות; Land of the Fathers). This is a common biblical and literary usage. Equivalent to 'Fatherland'.

- Erets Zavat Chalav Oudvash (ארץ זבת חלב ודבש; Land Flowing with Milk and Honey). This is a biblical term which is still sometimes used.

- Haarets Hatova (הארץ הטובה; The Good Land). Originated in the Book of Deuteronomy.

Uses by country

- The Soviet Union created homelands for some minorities in the 1920s, including the Volga German ASSR and the Jewish Autonomous Oblast. In the case of the Volga German ASSR, these homelands were later abolished, and their inhabitants deported to either Siberia or the Kazakh SSR.

- In the United States, the Department of Homeland Security was created soon after the 11 September 2001, terrorist attacks, as a means to centralize response to various threats. In a June 2002 column, Republican consultant and speechwriter Peggy Noonan expressed the hope that the Bush administration would change the name of the department, writing that, "The name Homeland Security grates on a lot of people, understandably. Homeland isn't really an American word, it's not something we used to say or say now".[15]

- In the apartheid era in South Africa, the concept was given a different meaning. The white government had designated approximately 25% of its non-desert territory for black tribal settlement. Whites and other non-blacks were restricted from owning land or settling in those areas. After 1948 they were gradually granted an increasing level of "home-rule". From 1976 several of these regions were granted independence. Four of them were declared independent nations by South Africa, but were unrecognized as independent countries by any other nation besides each other and South Africa. The territories set aside for the African inhabitants were also known as bantustans.[citation needed]

- In Australia, the term refers to relatively small Aboriginal settlements (referred to also as "outstations") where people with close kinship ties share lands significant to them for cultural reasons. Many such homelands are found across Western Australia, the Northern Territory, and Queensland. The homeland movement gained momentum in the 1970 and 1980s. Not all homelands are permanently occupied owing to seasonal or cultural reasons.[16] Much of their funding and support have been withdrawn since the 2000s.[17]

- In Turkish, the concept of "homeland", especially in the patriotic sense, is "ana vatan" (lit. mother homeland), while "baba ocağı" (lit. father's hearth) is used to refer to one's childhood home. (Note: The Turkish word "ocak" has the double meaning of january and fireplace, like the Spanish "hogar", which can mean "home" or "hearth".)[citation needed]

Land of one's home

In some languages, there are additional words that refer specifically to the place where one is home to, but is narrower in scope than one's nation, and often have some sort of nostalgic, fantastic, heritage connection, for example:

- In German language, heimat.

- In Dutch and Afrikaans, t(h)uisland, equivalent to the term bantustan

- In Japanese language, kokyō, or, furusato (故郷), or kyōdo (郷土).

- In Chinese languages, 故乡; 故鄉; gùxiāng or 家乡; 家鄉; jiāxiāng.

- In Vietnamese language, cố hương.

- In Korean language, 고향, gohyang, 故鄕.

See also

References

- ^ "Definition of Homeland". merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 23 December 2018.

- ^ Pitroipa, Abdel (14 July 2010). "Ces tirailleurs sénégalais qui ont combattu pour la France". L'Express (in French). Retrieved 14 August 2019.

- ^ Bloomsbury Publishing (20 November 2013). Historiae Mundi: Studies in Universal History. A&C Black. p. 97. ISBN 9781472519801.

- ^ Anthon, Charles (1867). Eneid of Virgil.

- ^ "Definition of FATHERLAND". merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 8 January 2019.

- ^ James, Caroline (May 2015). "Identity Crisis: Motherland or Fatherland?". Oxford Dictionaries. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 11 May 2015. Retrieved 14 August 2019.

- ^ Wierzbicka, Anna (21 July 1997). Understanding Cultures Through Their Key Words : English, Russian, Polish, German, and Japanese. Oxford University Press. pp. 173–175. ISBN 978-0-19-535849-0.

- ^ Stargardt, Nicholas (18 December 2007). Witnesses of War: Children's Lives Under the Nazis. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. p. 328. ISBN 9780307430304.

- ^ Wilensky, Gabriel (2010). Six Million Crucifixions. QWERTY Publishers. ISBN 9780984334643.

What we have to fight for is the freedom and independence of the fatherland, so that our people may be enabled to fulfill the mission assigned to it by the creator

- ^ "Nazi Germany reveals official pictures of its concentration camps". Life. Vol. 7, no. 8. Time Inc. 21 August 1939. p. 22. ISSN 0024-3019.

There is a road to freedom. Its milestones are Obedience, Endeavor, Honesty, Order, Cleanliness, Sobriety, Truthfulness, Sacrifice, and love of the Fatherland.

- ^ Wilhelmus-YouTube

- ^ Vaterland-YouTube

- ^ "Ziemia Ojców". 16 April 2012.

- ^ "Ziemia Ojców Naszych". Archived from the original on 14 May 2016. Retrieved 24 August 2019.

- ^ Noonan, Peggy (14 June 2002). "OpinionJournal – Peggy Noonan". Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 8 September 2007.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "The Encyclopedia of Aboriginal Australia". 1994.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Peterson, Nicolas; Myers, Fred, eds. (January 2016). Experiments in self-determination: Histories of the outstation movement in Australia [blurb]. Monographs in Anthropology. ANU Press. doi:10.22459/ESD.01.2016. ISBN 9781925022902. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

Further reading

- Landscape and Memory by Simon Schama (Random House, 1995)