Pontic Olbia

The ruins of Olbia | |

| Alternative name | Olbia |

|---|---|

| Location | Parutyne, Mykolaiv Oblast, Ukraine |

| Coordinates | 46°41′33″N 31°54′13″E / 46.69250°N 31.90361°E |

| Type | Settlement |

| Length | 1 mi (1.6 km) |

| Width | 0.5 mi (0.80 km) |

| Area | 50 ha (120 acres) |

| History | |

| Builder | Settlers from Miletus |

| Founded | 7th century BC |

| Abandoned | 4th century AD |

| Periods | Archaic Greek to Roman Imperial |

| Cultures | Greek, Roman |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1901–1915, 1924–1926 |

| Archaeologists | Boris Farmakovsky |

| Condition | Ruined |

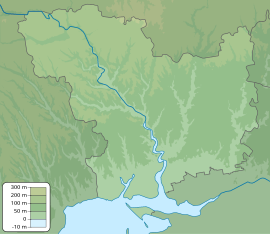

Pontic Olbia (Ancient Greek: Ὀλβία Ποντική; Ukrainian: Ольвія, romanized: Olviia) or simply Olbia is an archaeological site of an ancient Greek city on the shore of the Southern Bug estuary (Hypanis or Ὕπανις,) in Ukraine, near the village of Parutyne. The archaeological site is protected as the National Historic and Archaeological Preserve. The preserve is a research and science institute of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine. In 1938–1993 it was part of the NASU Institute of Archaeology as a department.

The Hellenic city was founded in the 7th century BC by colonists from Miletus. Its harbour was one of the main emporia on the Black Sea for the export of cereals, fish, and slaves to Greece, and for the import of Attic goods to Scythia.[1]

Layout

The site of the Greek colony covers the area of fifty hectares and its fortifications form an isosceles triangle about a mile long and half a mile wide.[2] The region was also the site of several villages (modern Victorovka and Dneprovskoe) which may have been settled by Greeks.[2]

As for the town itself, the lower town (now largely submerged by the Bug river) was occupied chiefly by the dockyards and the houses of artisans. The upper town was a main residential quarter, composed of square blocks and centered on the agora. The town was ringed by a defensive stone wall with towers.[3] The upper town was also the site of the first settlement on the site in the archaic period.[2] There is evidence that the town itself was laid out over a grid plan from the 6th century – one of the first after the town of Smyrna.[2]

By the later period of settlement, the city also included an acropolis and, from the 6th century BCE, a religious sanctuary.[2] In the early 5th century, a temple to Apollo Delphinios was also built on the site.[2]

History

Archaic and Classical periods

The Greek colony was highly important commercially and endured for a millennium. The first evidence of Greek settlement at the site comes from Berezan Island where pottery has been found dating from the late 7th century.[4] The name in Greek means "happy" or "rich". It is possible that it had been the site of an earlier native settlement and may even have been a peninsula rather than an island in antiquity.[4] It is now thought that the town of Berezan survived until the 5th century BCE when it was possibly absorbed into the growing Olbian settlement on the mainland.[4]

During the 5th century BCE, the colony was visited by Herodotus, who provides our best description of the city and its inhabitants from antiquity.[5]

It produced distinctive cast bronze money during the 5th century BCE in both the form of circular tokens with Gorgon heads and unique coins in the shape of leaping dolphins.[6] These are unusual considering the struck, round coins common in the Greek world. This form of money is said to have originated from sacrificial tokens used in the Temple of Apollo Delphinios.[citation needed]

M. L. West speculated that early Greek religion, especially the Orphic Mysteries, was heavily influenced by Central Asian shamanistic practices. A significant amount of Orphic graffiti unearthed in Olbia seems to testify that the colony was one major point of contact.[7]

Hellenistic and Roman periods

After the town adopted a democratic constitution in the 4th century BCE, its relations with Miletus were regulated by a treaty,[9] which allowed both states to coordinate their operations against Alexander the Great's general Zopyrion in the 4th century BCE. By the end of the 3rd century, the town declined economically[note 1] and accepted the overlordship of King Skilurus of Scythia. It flourished under Mithridates Eupator but was sacked by the Getae under Burebista, a catastrophe which brought Olbia's economic prominence to an abrupt end.

Having lost two-thirds of its settled area, Olbia was restored by the Romans, albeit on a small scale and probably with a largely barbarian population. Dio of Prusa visited the town and described it in his Borysthenic Discourse (the town was often called Borysthenes, after the river).

The settlement, incorporated into the Roman province of Lower Moesia, was eventually abandoned in the 4th century CE, when it was burnt at least twice in the course of the Gothic Wars.

Excavation

The site of Olbia, designated an archaeological reservation, is situated near the village of Parutyne in Mykolaiv Raion. Before 1902, the site was owned by the Counts Musin-Pushkins, who did not allow any excavations on their estate. Professional excavations were conducted under Boris Farmakovsky from 1901 to 1915 and from 1924 to 1926. As the site was never reoccupied, archaeological finds (particularly inscriptions and sculpture) proved rich. Today archaeologists are under pressure to explore the site, which is being eroded by the Black Sea. At 2016 started in Olbia excavations of the Polish Archaeological Mission "Olbia" of the National Museum in Warsaw headed by Alfred Twardecki. Many of the more notable finds from the period are visible in the Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg, Russia.

Notable finds from the town include an archaic Greek house in a good state of preservation from the area of the later acropolis and a private letter (written on a lead tablet) dating to around 500 BCE, complaining about an attempt to claim a slave.[4]

See also

Notes

- ^ A board of food commissioners was set up to distribute cereals among the population.

References

- ^ Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece (ed. by Nigel Guy Wilson). Routledge (UK), 2005. ISBN 0-415-97334-1. Page 510.

- ^ a b c d e f Boardman, John (1980). The Greeks Overseas: Their Early Colonies and Trade. London: Thames and Hudson Ltd. pp. 251. ISBN 9780500250693.

- ^ Wasowicz, Aleksandra. Olbia Pontique et son territoire : l'aménagement de l'espace Paris: Belles-lettres, 1975. OCLC 3035787

- ^ a b c d Boardman, John (1980). The Greeks Overseas: Their Early Colonies and Trade. London: Thames and Hudson Ltd. pp. 250. ISBN 9780500250693.

- ^ Herodotus, Histories, 4.19

- ^ "Olbia". Odessa Numismatic Museum.

- ^ West, M. L., The Orphic Poems, Oxford : Clarendon Press, 1983. ISBN 0198148542. Cf. p.146

- ^ Sear, David R. (1978). Greek Coins and Their Values . Volume I: Europe (pp. 168, coin # 1685). Seaby Ltd., London. ISBN 0 900652 46 2

- ^ Serhii Plokhy (2015) "The Gates of Europe : A History of Ukraine" New York : Basic Books

Further reading

- Braund, David; Kryzhitskiy, S. D., eds. (2007). Classical Olbia and the Scythian World: From the Sixth Century BC to the Second Century AD. Proceedings of the British Academy. Vol. 142. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.5871/bacad/9780197264041.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-726404-1.

- Karjaka, Alexander V. (2008). "The Defense Wall in the Northern Part of the Lower City of Olbia Pontike". In Bilde, Pia Guldager; Petersen, Jane Hjarl (eds.). Meetings of Cultures in the Black Sea Region: Between Conflict and Coexistence. Black Sea Studies. Vol. 8. Aarhus: Aarhus University Press. pp. 163–180. ISBN 978-87-7934-419-8.

- Karjaka, Alexander V. (2008). "The Demarcation System of the Agricultural Environment of Olbia Pontike". In Bilde, Pia Guldager; Petersen, Jane Hjarl (eds.). Meetings of Cultures in the Black Sea Region: Between Conflict and Coexistence. Black Sea Studies. Vol. 8. Aarhus: Aarhus University Press. pp. 181–192. ISBN 978-87-7934-419-8.

- Kozlovskaya, Valeriya (2008). "The Harbour of Olbia". Ancient Civilizations from Scythia to Siberia. 14 (1–2): 25–65. doi:10.1163/092907708X339562.

- Krapivina, Valentina; Diatroptov, Pavel (2005). "An Inscription of Mithradates VI Eupator's Governor from Olbia". Ancient Civilizations from Scythia to Siberia. 11 (3–4): 167–180. doi:10.1163/157005705775009435.

- Krapivina, Valentyna V. (2010). "Ceramics from Sinope in Olbia Pontica". Ancient Civilizations from Scythia to Siberia. 16 (1–2): 467–477. doi:10.1163/157005711X560453.

- Osborne, Robin (2008). "Reciprocal Strategies: Imperialism, Barbarism and Trade in Archaic and Classical Olbia". In Bilde, Pia Guldager; Petersen, Jane Hjarl (eds.). Meetings of Cultures in the Black Sea Region: Between Conflict and Coexistence. Black Sea Studies. Vol. 8. Aarhus: Aarhus University Press. pp. 333–346. ISBN 978-87-7934-419-8.

External links

- Ancient Coinage of Sarmatia, Olbia

- Greek inscriptions of Olbia in English translation

- Pyotr Karyshkovsky Coins of Olbia: Essay of Monetary Circulation of the North-western Black Sea Region in Antique Epoch. Киев, 1988. ISBN 5-12-000104-1.

- Pyotr KaryshkovskyCoinage and Monetary Circulation in Olbia (6th century B.C. – 4th century A.D.) Odessa (2003). ISBN 966-96181-0-X.

- Site of the Polish Archaeological Mission "Olbia"