Nuclear arms race

| Nuclear weapons |

|---|

|

| Background |

| Nuclear-armed states |

|

The nuclear arms race was an arms race competition for supremacy in nuclear warfare between the United States, the Soviet Union, and their respective allies during the Cold War. During this same period, in addition to the American and Soviet nuclear stockpiles, other countries developed nuclear weapons, though no other country engaged in warhead production on nearly the same scale as the two superpowers.

World War II

The first nuclear weapon was created by the United States of America during the Second World War and was developed to be used against the Axis powers.[1] Scientists of the Soviet Union were aware of the potential of nuclear weapons and had also been conducting research in the field.[2]

The Soviet Union was not informed officially of the Manhattan Project until Stalin was briefed at the Potsdam Conference on July 24, 1945, by U.S. President Harry S. Truman,[3][4] eight days after the first successful test of a nuclear weapon. Despite their wartime military alliance, the United States and Britain had not trusted the Soviets enough to keep knowledge of the Manhattan Project safe from German spies; there were also concerns that, as an ally, the Soviet Union would request and expect to receive technical details of the new weapon.[citation needed]

When President Truman informed Stalin of the weapons, he was surprised at how calmly Stalin reacted to the news and thought that Stalin had not understood what he had been told. Other members of the United States and British delegations who closely observed the exchange formed the same conclusion.[4]

In fact, Stalin had long been aware of the program,[5] despite the Manhattan Project's having a secret classification so high that, even as vice president, Truman did not know about it or the development of the weapons (Truman was not informed until shortly after he became president).[5] A ring of spies operating within the Manhattan Project, (including Klaus Fuchs[6] and Theodore Hall) had kept Stalin well informed of American progress.[7] They provided the Soviets with detailed designs of the implosion bomb and the hydrogen bomb.[citation needed] Fuchs' arrest in 1950 led to the arrests of many other suspected Russian spies, including Harry Gold, David Greenglass, and Ethel and Julius Rosenberg; the latter two were tried and executed for espionage in 1951.[8]

In August 1945, on Truman's orders, two atomic bombs were dropped on Japanese cities. The first bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, and the second bomb was dropped on Nagasaki by the B-29 bombers named Enola Gay and Bockscar respectively.

Shortly after the end of the Second World War in 1945, the United Nations was founded. During the United Nation's first General Assembly in London in January 1946, they discussed the future of nuclear weapons and created the United Nations Atomic Energy Commission. The goal of this assembly was to eliminate the use of all Nuclear weapons. The United States presented their solution, which was called the Baruch Plan.[9] This plan proposed that there should be an international authority that controls all dangerous atomic activities. The Soviet Union disagreed with this proposal and rejected it. The Soviets' proposal involved universal nuclear disarmament. Both the American and Soviet proposals were refused by the UN.[10]

Early Cold War

Warhead development

In the years immediately after the Second World War, the United States had a monopoly on specific knowledge of and raw materials for nuclear weaponry. American leaders hoped that their exclusive ownership of nuclear weapons would be enough to draw concessions from the Soviet Union, but this proved ineffective.[citation needed]

Just six months after the UN General Assembly, the United States conducted its first post-war nuclear tests — Operation Crossroads.[11] The purpose of this operation was to test the effect of nuclear explosions on ships. These tests were performed at Bikini Atoll in the Pacific on 95 ships, including German and Japanese ships that were captured during World War II. One plutonium implosion-type bomb was detonated over the fleet, while the other one was detonated underwater.

In secrecy, the Soviet government was working on building its own atomic weapons. During the war, Soviet efforts had been limited by a lack of uranium, but new supplies discovered in Eastern Europe provided a steady supply while the Soviets developed a domestic source. While American experts had predicted that the Soviet Union would not have nuclear weapons until the mid-1950s, the first Soviet bomb was detonated on August 29, 1949. The bomb, named "First Lightning" by the West, was more or less a copy of "Fat Man", one of the bombs the United States had dropped on Japan in 1945.

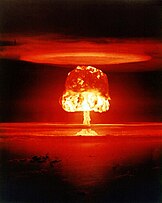

Both governments spent massive amounts to increase the quality and quantity of their nuclear arsenals. Both nations quickly began the development of thermonuclear weapons, which can achieve vastly greater explosive yields. The United States detonated the first hydrogen bomb on November 1, 1952, on Enewetak, an atoll in the Pacific Ocean.[12] Code-named "Ivy Mike", the project was led by Edward Teller, a Hungarian-American nuclear physicist. It created a cloud 100 miles (160 km) wide and 25 miles (40 km) high, killing all life on the surrounding islands.[13] Again, the Soviets surprised the world by exploding a deployable thermonuclear device in August 1953, although it was not a true multi-stage hydrogen bomb. However, it was small enough to be dropped from an airplane, making it ready for use. The development of these two Soviet bombs was greatly aided by the Russian spies Harry Gold and Klaus Fuchs.[citation needed]

On March 1, 1954, the U.S. conducted the Castle Bravo test, which tested another hydrogen bomb on Bikini Atoll.[14] Scientists significantly underestimated the size of the bomb, thinking it would yield 5 megatons. However, it yielded 14.8 megatons, the highest yield ever achieved by an American nuclear device.[15][16] The explosion was so large the nuclear fallout exposed residents up to 300 miles (480 km) away to significant amounts of radiation.[citation needed] They were eventually evacuated, but most experienced radiation poisoning; one person was killed, a crew member on a Japanese fishing boat which was 90 miles (140 km) from the bomb test site when the explosion occurred.[17]

The Soviet Union detonated its first "true" hydrogen bomb on November 22, 1955, which had a yield of 1.6 megatons. On October 30, 1961, the Soviets detonated a hydrogen bomb with a yield of approximately 58 megatons.[18]

With both sides in the Cold War having nuclear capability, an arms race developed, with the Soviet Union attempting first to catch up and then to surpass the Americans.[19]

Delivery vehicles

Strategic bombers were the primary delivery method at the beginning of the Cold War.

Missiles had long been regarded the ideal platform for nuclear weapons and were potentially a more effective delivery system than bombers. Starting in the 1950s, medium-range ballistic missiles and intermediate-range ballistic missiles ("IRBM"s) were developed for delivery of tactical nuclear weapons, and the technology developed to the progressively longer ranges, eventually becoming intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs).[citation needed] On October 4, 1957, the Soviet Union launched the first artificial satellite, Sputnik 1, into an orbit around the Earth, demonstrating that Soviet ICBMs were capable of reaching any point on the planet. The United States launched its first satellite, Explorer 1, on January 31, 1958.

Meanwhile, submarine-launched ballistic missiles were also developed. By the mid-1960s, the "triad" of nuclear weapon delivery was established, with each side deploying bombers, ICBMs, and SLBMs, in order to ensure that even if a defense was found against one delivery method, the other methods would still be available.

Some[who?] in the United States during the early 1960s pointed out that although all of the individual components of nuclear missiles had been tested separately (warheads, navigation systems, rockets), it was infeasible to test them all combined. Critics charged that it was not really known how a warhead would react to the gravity forces and temperature differences encountered in the upper atmosphere and outer space, and Kennedy was unwilling to run a test of an ICBM with a live warhead. The closest event to an actual test was 1962's Operation Frigate Bird, in which the submarine USS Ethan Allen (SSBN-608) launched a Polaris A2 missile over 1,000 miles (1,600 km) to the nuclear test site at Christmas Island. It was challenged by, among others, Curtis LeMay, who put missile accuracy into doubt to encourage the development of new bombers. Other critics pointed out that it was a single test which could be an anomaly; that it was a lower-altitude SLBM and therefore was subject to different conditions than an ICBM; and that significant modifications had been made to its warhead before testing.

| Year | Launchers | Warheads | Megatonnage | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| United States | Soviet Union | United States | Soviet Union | United States | Soviet Union | |

| 1964 | 2,416 | 375 | 6,800 | 500 | 7,500 | 1,000 |

| 1966 | 2,396 | 435 | 5,000 | 550 | 5,600 | 1,200 |

| 1968 | 2,360 | 1,045 | 4,500 | 850 | 5,100 | 2,300 |

| 1970 | 2,230 | 1,680 | 3,900 | 1,800 | 4,300 | 3,100 |

| 1972 | 2,230 | 2,090 | 5,800 | 2,100 | 4,100 | 4,000 |

| 1974 | 2,180 | 2,380 | 8,400 | 2,400 | 3,800 | 4,200 |

| 1976 | 2,100 | 2,390 | 9,400 | 3,200 | 3,700 | 4,500 |

| 1978 | 2,058 | 2,350 | 9,800 | 5,200 | 3,800 | 5,400 |

| 1980 | 2,042 | 2,490 | 10,000 | 7,200 | 4,000 | 6,200 |

| 1982 | 2,032 | 2,490 | 11,000 | 10,000 | 4,100 | 8,200 |

Mutual assured destruction (MAD)

By the mid-1960s both the United States and the Soviet Union had enough nuclear power to obliterate[clarification needed] their opponent.[citation needed] Both sides developed a capability to launch a devastating attack even after sustaining a full assault from the other side (especially by means of submarines), called a second strike. This policy became known as Mutual Assured Destruction: both sides knew that any attack upon the other would be devastating to themselves, thus in theory restraining them from attacking the other.

Both Soviet and American experts hoped to use nuclear weapons for extracting concessions from the other, or from other powers such as China, but the risk connected with using these weapons was so grave that they refrained from what John Foster Dulles referred to as brinkmanship. While some, like General Douglas MacArthur, argued nuclear weapons should be used during the Korean War, both Truman and Eisenhower opposed the idea.[citation needed]

Both sides were unaware of the details of the capacity of the enemy's arsenal of nuclear weapons. The Americans suffered from a lack of confidence, and in the 1950s they believed in a non-existing bomber gap. Aerial photography later revealed that the Soviets had been playing a sort of Potemkin village game with their bombers in their military parades, flying them in large circles, making it appear they had far more than they truly did. The 1960 American presidential election saw accusations of a wholly spurious missile gap between the Soviets and the Americans. On the other side, the Soviet government exaggerated the power of Soviet weapons to the leadership and Soviet first secretary Nikita Khrushchev.[citation needed]

Initial nuclear proliferation

In addition to the United States and the Soviet Union, three other nations, the United Kingdom,[22] the People's Republic of China,[23] and France[24] developed nuclear weapons during the early cold war years.

In 1952, the United Kingdom became the third nation to test a nuclear weapon when it detonated an atomic bomb in Operation Hurricane[25] on October 3, 1952, which had a yield of 25 kilotons. Despite major contributions to the Manhattan Project by both Canadian and British governments, the U.S. Congress passed the Atomic Energy Act of 1946, which prohibited multi-national cooperation on nuclear projects. The Atomic Energy Act fueled resentment from British scientists and Winston Churchill, as they believed that there were agreements regarding post-war sharing of nuclear technology and led to Britain's developing its nuclear weapons. Britain did not begin planning the development of its nuclear weapon until January 1947. Because of Britain's small size, they decided to test their bomb on the Montebello Islands, off the coast of Australia. Following this successful test, under the leadership of Churchill, Britain decided to develop and test a hydrogen bomb. The first successful hydrogen bomb test occurred on November 8, 1957, which had a yield of 1.8 megatons.[26] An amendment to the Atomic Energy Act in 1958 allowed nuclear cooperation once again, and British-U.S. nuclear programs resumed. During the Cold War, British nuclear deterrence came from submarines and nuclear-armed aircraft. The Resolution-class ballistic missile submarines armed with the American-built Polaris missile provided the sea deterrent, while aircraft such as the Avro Vulcan, SEPECAT Jaguar, Panavia Tornado and several other Royal Air Force strike aircraft carrying the WE.177 gravity bomb provided the air deterrent.

France became the fourth nation to possess nuclear weapons on February 13, 1960, when the atomic bomb "Gerboise Bleue" was detonated in Algeria,[27] then still a French colony (formally a part of Metropolitan France). France began making plans for a nuclear-weapons program shortly after the Second World War, but the program did not begin until the late 1950s. Eight years later, France conducted its first thermonuclear test above Fangatuafa Atoll. It had a yield of 2.6 megatons.[28] This bomb significantly contaminated the atoll with radiation for six years, making it off-limits to humans. During the Cold War, the French nuclear deterrent was centered around the Force de frappe, a nuclear triad consisting of Dassault Mirage IV bombers carrying such nuclear weapons as the AN-22 gravity bomb and the ASMP stand-off attack missile, Pluton and Hades ballistic missiles, and the Redoutable-class submarine armed with strategic nuclear missiles.

The People's Republic of China became the fifth nuclear power on October 16, 1964, when it detonated a 25 kiloton uranium-235 bomb in a test codenamed 596[29] at Lop Nur. In the late 1950s, China began developing nuclear weapons with substantial Soviet assistance in exchange for uranium ore. However, the Sino-Soviet ideological split in the late 1950s developed problems between China and the Soviet Union. This caused the Soviets to cease helping China develop nuclear weapons. However, China continued developing nuclear weapons without Soviet support and made remarkable progress in the 1960s.[30] Owing to Soviet/Chinese tensions, the Chinese might have used nuclear weapons against either the United States or the Soviet Union in the event of a nuclear war between the United States and the Soviet Union.[citation needed] During the Cold War, the Chinese nuclear deterrent consisted of gravity bombs carried aboard H-6 bomber aircraft, missile systems such as the DF-2, DF-3, and DF-4,[31] and in the later stages of the Cold War, the Type 092 ballistic missile submarine. On June 14, 1967, China detonated its first hydrogen bomb.

Cuban Missile Crisis

On January 1, 1959, the Cuban government fell to communist revolutionaries, propelling Fidel Castro into power. The communist Soviet Union supported and praised Castro and his resistance, and the revolutionary government was recognized by the Soviet Union on January 10. When the United States began boycotting Cuban sugar, the Soviet Union began purchasing large quantities to support the Cuban economy in return for fuel and eventually placing nuclear ballistic missiles on Cuban soil. These missiles would be capable of reaching the United States very quickly. On October 14, 1962, an American spy plane discovered these nuclear missile sites under construction in Cuba.[32]

President Kennedy immediately called a series of meetings for a small group of senior officials to debate the crisis. The group was split between a militaristic solution and a diplomatic one. President Kennedy ordered a naval blockade around Cuba and all military forces to DEFCON 3. As tensions increased, Kennedy eventually ordered U.S. military forces to DEFCON 2. This is considered the closest the world has been to a nuclear war. While the U.S. military had been ordered to DEFCON 2, the theory of mutually assured destruction suggests that entry into nuclear war is an unlikely possibility. While the public perceived the Cuban Missile Crisis as a time of near mass destruction, the leaders of the United States and the Soviet Union were working confidentially in order to allow the crisis to come to a peaceful conclusion. Soviet First Secretary Khrushchev wrote to President Kennedy in a telegram on October 26, 1962, saying that, "Consequently, if there is no intention to tighten that knot and thereby to doom the world to the catastrophe of thermonuclear war, then let us not only relax the forces pulling on the ends of the rope, let us take measures to untie that knot."[33]

Eventually, on October 28, through much discussion between U.S and Soviet officials, Khrushchev announced that the Soviet Union would withdraw all missiles from Cuba. Shortly afterwards, the U.S. withdrew all their nuclear missiles from Turkey in secret – the presence of the missiles having threatened the Soviets. Information that the U.S. had withdrawn their Jupiter Missiles from Turkey remained confidential for decades, causing the result of the negotiations between the two nations to appear to the world as a major U.S. victory. This ultimately led to the downfall of Soviet leader Khrushchev.[citation needed]

Détente

By the 1970s, with the Cold War's entering its 30th year with no direct conflict between the United States and the Soviet Union, the superpowers entered a period of reduced conflict, in which the two powers engaged in trade and exchanges with each other. This period was known as détente.

This period included negotiation of a number of arms control agreements, building with the Nuclear Test Ban Treaty in the 1950s, but with significant new treaties negotiated in the 1970s. These treaties were only partially successful. Although both states continued to hold massive numbers of nuclear weapons and research more effective technology, the growth in number of warheads was first limited, and later, with the START I, reversed.

Treaties

In 1958, both the U.S. and Soviet Union informally agreed to suspend nuclear testing. However, this agreement was ended when the Soviets resumed testing in 1961, followed by a series of nuclear tests conducted by the U.S. These events led to much political fallout, as well as the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962. It was felt by American and Soviet leaders that something had to be done to ease the significant tensions between these two countries, so on October 10, 1963, the Limited Test Ban Treaty (LTBT) was signed.[34] This was an agreement between the U.S., the Soviet Union, and the U.K., which significantly restricted nuclear testing. All atmospheric, underwater, and outer space nuclear testing were agreed to be halted, but testing was still allowed underground. An additional 113 countries have signed this treaty since 1963.

SALT I and SALT II limited the size of the U.S. arsenal. Bans on nuclear testing, anti-ballistic missile systems, and weapons in space all attempted to limit the expansion of the arms race through the Partial Test Ban Treaty.

In November 1969, Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT) begun. This was primarily due to the economic impact that nuclear testing and production had on both U.S. and Soviet economies. The SALT I Treaty, which was signed in May 1972, produced an agreement on two significant documents. These were the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty (ABM Treaty) and the Interim Agreement on the Limitation of Strategic Offensive Arms.[35] The ABM treaty limited each country to two ABM sites, while the Interim Agreement froze each country's number of intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) and submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs) at current levels for five years. This treaty significantly reduced nuclear-related costs as well as the risk of nuclear war. However, SALT I failed to address how many nuclear warheads could be placed on a single missile. A new technology, known as multiple-independently targetable re-entry vehicle (MIRV), allowed single missiles to hold and launch multiple nuclear missiles at targets while in mid-air. Over the next 10 years, the Soviet Union and U.S. added 12,000 nuclear warheads to their already built arsenals.

Throughout the 1970s, both the Soviet Union and United States replaced older warheads and missiles with newer, more powerful and effective ones. On June 18, 1979, the SALT II treaty was signed in Vienna. This treaty limited both sides' nuclear arsenals and technology. However, in light of the Soviet Union's invasion of Afghanistan in December 1979, the United States Senate never ratified the SALT II treaty. This ended the treaty negotiations as well as the era of détente.[36]

In 1991, the START (Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty) was negotiated between the U. S. and the Soviet Union, to reduce the number and limit the capabilities of limitation of strategic offensive arms. This was eventually succeeded by the START II, START III, and New START treaties.

Reagan and the Strategic Defense Initiative

Despite détente, both sides continued to develop and introduce not only more accurate weapons, but weapons with more warheads ("MIRVs"). The presidency of Ronald Reagan proposed a missile defense programme tagged the Strategic Defense Initiative, a space-based anti-ballistic missile system derided as "Star Wars" by its critics; simultaneously, missile defense was also being researched in the Soviet Union. However, the SDI would require technology that had not yet been developed, or even researched. This system proposed both space- and earth-based laser battle stations. It would also need sensors on the ground, in the air, and in space with radar, optical, and infrared technology to detect incoming missiles.[37] Simultaneously, however, Reagan initiated negotiations with Mikhail Gorbachev, ultimately resulting in the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty on reducing nuclear stockpiles.

Owing to high costs and complex technology for its time, the scope of the SDI project was reduced from defense against a massive attack to a system for defending against limited attacks, transitioning into the Ballistic Missile Defense Organization.

The end of the Cold War

During the mid-1980s, the U.S-Soviet relations significantly improved, Mikhail Gorbachev assumed control of the Soviet Union after the deaths of several former Soviet leaders and announced a new era of "perestroika" and "glasnost," meaning restructuring and openness respectively. Gorbachev proposed a 50% reduction of nuclear weapons for both the U.S and Soviet Union at the meeting in Reykjavik, Iceland in October 1986. However, the proposal was refused due to disagreements over Reagan's SDI. Instead, the Intermediate Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty was signed on December 8, 1987, in Washington, which eliminated an entire class of nuclear weapons.[38]

Owing to the dramatic economic and social changes occurring within the Soviet Union, many of its constituent republics began to declare their independence. With the wave of revolutions sweeping across Eastern-Europe, the Soviet Union was unable to impose its will on its satellite states and so its sphere of influence slowly diminished. By December 16, 1991, all of the republics had declared independence from the Union. The Soviet leader, Mikhail Gorbachev resigned as the country's president on December 25 and the Soviet Union was declared non-existent the following day.

Post–Cold War

With the end of the Cold War, the United States and Russia cut down on nuclear weapons spending.[citation needed] Fewer new systems were developed, and both arsenals were reduced, although both countries maintain significant stocks of nuclear missiles. In the United States, stockpile stewardship programs have taken over the role of maintaining the aging arsenal.[39]

After the Cold War ended, large inventories of nuclear weapons and facilities remained. Some are being recycled, dismantled, or recovered as valuable substances.[citation needed] Large amounts of money and resources – which would have been spent on developing nuclear weapons in the Soviet Union, had the arms race continued[citation needed] – were instead used for repairing the environmental damage produced by the nuclear arms race, and almost all former production sites are now major cleanup sites.[citation needed] In the United States, the plutonium production facility at Hanford, Washington, and the plutonium pit fabrication facility at Rocky Flats, Colorado, are among the most polluted sites.[citation needed]

Military policies and strategies have been modified to reflect the increasing intervals without major confrontation. In 1995, United States policy and strategy regarding nuclear proliferation was outlined in the document "Essentials of Post–Cold War Deterrence", produced by the Policy Subcommittee of the Strategic Advisory Group (SAG) of the United States Strategic Command.

21st century nuclear arms race

On 13 December 2001, George W. Bush gave Russia notice of the United States' withdrawal from the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty. This led to the eventual creation of the American Missile Defense Agency. Russian President Vladimir Putin responded to the withdrawal by ordering a build-up of Russia's nuclear capabilities, designed to counterbalance U.S. capabilities.[40]

On April 8, 2010, U.S. President Barack Obama and Russian President Dmitry Medvedev signed the New START Treaty, which called for a fifty percent reduction of strategic nuclear missile launchers and a curtailment of deployed nuclear warheads.[41] The U.S. Senate ratified the treaty in December 2010 by a three-quarter majority.

On December 22, 2016, U.S. President Donald Trump proclaimed in a tweet that "the United States must greatly strengthen and expand its nuclear capability until such time as the world comes to its senses regarding nukes,"[42] effectively challenging the world to re-engage in a race for nuclear dominance. The next day, Trump reiterated his position to Morning Joe host Mika Brzezinski of MSNBC, stating: "Let it be an arms race. We will outmatch them at every pass and outlast them all."[43]

In October 2018, the former Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev commented that U.S. withdrawal from the INF nuclear treaty is "not the work of a great mind" and that "a new arms race has been announced".[44][45]

In 2019, Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Sergey Ryabkov warned about the risk of nuclear war, as negative dynamics had been noticeable over the previous year. He urged the nuclear states to build channels on forestalling potential incidents in order to lower the risks.[46][clarification needed]

According to a peer-reviewed study published in the journal Nature Food in August 2022,[47] a full-scale nuclear war between the United States and Russia, which together hold more than 90% of the world's nuclear weapons, would kill 360 million people directly and more than 5 billion (80% of humanity) indirectly by starvation during a nuclear winter. Roughly 99% of the people in the US, Europe, Russia and China would starve to death if they did not die of something else sooner with 95% of the fatalities being in countries not initially involved.[48][49][50]

On February 21, 2023, Russian President Vladimir Putin suspended Russia's participation in the New START nuclear arms reduction treaty with the United States,[51] saying that Russia would not allow the US and NATO to inspect its nuclear facilities.[52]

In July 2024, the Biden administration announced its intention to deploy long-range missiles in Germany starting in 2026 that could hit Russian territory within 10 minutes. In response, Russian President Putin warned of a Cold War-style missile crisis and threatened to deploy long-range missiles within striking distance of the West.[53][54] US weapons in Germany would include SM-6 and Tomahawk cruise missiles and hypersonic weapons.[54] The United States' decision to deploy long-range missiles in Germany has been compared to the deployment of Pershing II launchers in Western Europe in 1979.[55][54] Critics say the move would trigger a new arms race.[56] According to Russian military analysts, it would be extremely difficult to distinguish between a conventionally armed missile and a missile carrying a nuclear warhead, and Russia could respond by deploying longer-range nuclear systems targeting Germany.[57]

In August 2024, The Economist reported that "a new nuclear arms race draws closer", as the U.S. is considering increasing its nuclear forces in response to escalating threats and rapid nuclear expansions by China and Russia, as well as North Korea's advancements in missile technology and Iran's advancement as a "threshold" nuclear state.[58]

India and Pakistan

In South Asia, India and Pakistan have also engaged in a technological nuclear arms race since the 1970s. The nuclear competition started in 1974 with India detonating a device, codenamed Smiling Buddha, at the Pokhran region of the Rajasthan state.[59] The Indian government called this test a "peaceful nuclear explosion", but according to independent sources, it was actually part of an accelerated covert nuclear program of India.[60]

This test generated great concern and doubts in Pakistan, with fear it would be at the mercy of its long-time arch-rival. Pakistan had its own covert atomic bomb projects in 1972 which ran for many years since the first Indian weapon was detonated. After the 1974 test, the pace of Pakistan's atomic bomb program significantly accelerated, culminating in successfully building its own atomic weapons. In the last few decades of the 20th century, India and Pakistan began to develop nuclear-capable rockets and nuclear military technologies. Finally, in 1998, India – under Atal Bihari Vajpayee's government – test detonated five more nuclear weapons. Domestic pressure within Pakistan began to build and Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif ordered a test, detonating six nuclear weapons (Chagai-I and Chagai-II) in retaliation and to act as a deterrent.[citation needed]

According to a peer-reviewed study published in the journal Nature Food in August 2022, a nuclear war between India and Pakistan could kill more than 2 billion indirectly by starvation during a nuclear winter.[61]

Defense against nuclear attacks

From the beginning of the Cold War, The United States, Russia, and other nations have all attempted to develop anti-ballistic missiles. The United States developed the LIM-49 Nike Zeus in the 1950s in order to destroy incoming ICBMs.

Russia has also developed ABM missiles, in the form of the A-35 anti-ballistic missile system and the later A-135 anti-ballistic missile system. Chinese state media has also announced that China has tested anti-ballistic missiles,[62] though specific information is not public.

In November 2006, India – with an initiative called the Indian Ballistic Missile Defence Programme – successfully tested its Prithvi Air Defense (PAD) anti-ballistic missile, followed by testing of the Advanced Air Defense (AAD) anti-ballistic missile in December 2007.[63][64]

Nuclear disarmament

Nuclear disarmament is one of four different norms in the aid of getting rid of nuclear weapons.[65] This norm can include arms control, arms reduction to elimination, prohibition, and stigmatization.[65]

This has been a hard norm to implement. Most of the conditions, the weight, strategy, timing, conditionality, and compliance have been contested.[65]

First the United States announced on September 27, 1991, that they would be destroying the ground-launched short-range nuclear weapons.[66] Mikhail Gorbachev, who was the President of the Soviet Union at that time, removed nuclear warheads from air defense missiles and nuclear artillery munitions.[66]

In 2017, the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons Treaty gives the representation of self-empowerment.[65] This treaty did not involve the states or their allies that had nuclear weapons.[65]

A lot of debate has occurred about nuclear disarmament. Debates over treaties in reducing and getting rid of nuclear weapons all together have been ongoing since the Cold War ended.

In 2010, there was a debate over the New Strategic Arms Reduction (START) treaty.[67] This treaty was negotiated between the United States and Russia.[67]

Since this has been an ongoing endeavor, a lot of the non-nuclear states are fighting to get the states that do have nuclear weapons to abide by what they believe to be the most recent obligations.[67]

Both the United States and Russian Presidents agreed to destroy nuclear weapons they contained.[66]

See also

- Arms race

- Nuclear warfare

- Nuclear holocaust

- Nuclear terrorism

- Space Race

- Artificial intelligence arms race

- Cold War

- Essentials of Post–Cold War Deterrence

- Deterrence theory

- Nuclear disarmament

- Historical nuclear weapons stockpiles and nuclear tests by country

- Brinkmanship (Cold War)

Nuclear technology portal

Nuclear technology portal

Notes

- ^ "Key Issues: Nuclear Weapons: History: Pre Cold War: Manhattan Project". nuclearfiles.org.

- ^ "The Soviet Nuclear Weapons Program". nuclearweaponarchive.org. 12 December 1997.

- ^ The Potsdam Conference between allied forces Archived 2007-10-24 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b "Atomic Bomb: Decision – Truman Tells Stalin, July 24, 1945". dannen.com.

- ^ a b Potsdam Note (Animation) Archived 2007-11-16 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Aiuto, Russell. "Klaus Fuchs: Atom Bomb Spy". Crime Library. Archived from the original on 9 February 2015.

- ^ Mike Fisk, Chief Information Officer, Los Alamos National Laboratory, Operated Los Alamos National Security, LLC, for the U.S. Department of Energy. "Our History". lanl.gov.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Atomic Espionage". www.atomicarchive.com.

- ^ "The Beginnings of the Cold War". Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- ^ "United States Relations with Russia: The Cold War". U.S. Department of State. June 2007.

- ^ "Operation Crossroads". Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- ^ "The Mike Test". Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- ^ "The Soviet Atomic Bomb". Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- ^ "The BRAVO Test". www.atomicarchive.com.

- ^ "Operation Castle". nuclearweaponarchive.org. Retrieved 23 September 2017.

- ^ Rowberry, Ariana (30 November 2001). "Castle Bravo: The Largest U.S. Nuclear Explosion". Brookings Institution. Retrieved 23 September 2017.

- ^ Oishi, Matashichi; Maclellan, Nic (2017), "The fisherman", Grappling with the Bomb, Britain's Pacific H-bomb tests, ANU Press, pp. 55–68, ISBN 9781760461379, JSTOR j.ctt1ws7w90.9

- ^ "The Soviet Response". www.atomicarchive.com.

- ^ "More accurate than the "race" metaphor is the observation that if it was a contest at all, the Americans walked while the Soviets trotted. There was race-but to the extent that there was an arms competition, it was almost entirely on the Soviets side, first to catch up and then to surpass the Americans." --Herman Kahn (1962) Thinking about the Unthinkable, Horizon Press.

- ^ Gerald Segal, The Simon & Schuster Guide to the World Today, (Simon & Schuster, 1987), p. 82

- ^ Edwin Bacon, Mark Sandle, "Brezhnev Reconsidered", Studies in Russian and East European History and Society (Palgrave Macmillan, 2003)

- ^ "United Kingdom Nuclear Forces". fas.org.

- ^ "China Nuclear Forces". fas.org.

- ^ "France Nuclear Forces". fas.org.

- ^ A toxic legacy: British nuclear weapons testing in Australia. Wayward Governance: Illegality and Its Control in the Public Sector. Australian Institute of Criminology. 2018-10-21. pp. 235–253. ISBN 978-0-642-14605-2. Archived from the original on 2008-07-28. Retrieved 2007-10-27.

- ^ "Britain Goes Nuclear". www.atomicarchive.com.

- ^ Chapitre II, Les premiers essais Français au Sahara : 1960–1966 Archived 2017-07-01 at the Wayback Machine Senat.fr (in French)

- ^ "France Joins the Club". www.atomicarchive.com.

- ^ "China's Nuclear Weapons". nuclearweaponarchive.org.

- ^ "Chinese Becomes A Nuclear Nation". www.atomicarchive.com.

- ^ "Theater Missile Systems". fas.org.

- ^ "Cuban Missile Crisis". www.atomicarchive.com.

- ^ "Document 65 – Foreign Relations of the United States, 1961–1963, Volume VI, Kennedy-Khrushchev Exchanges – Historical Documents – Office of the Historian." Document 65 – Foreign Relations of the United States, 1961–1963, Volume VI, Kennedy-Khrushchev Exchanges – Historical Documents – Office of the Historian. Accessed October 30, 2014.

- ^ "Limited Test Ban Treaty". www.atomicarchive.com. Retrieved 2021-01-17.

- ^ "Easing The Tensions". www.atomicarchive.com.

- ^ "The Arms Race Resumes". www.atomicarchive.com.

- ^ "Reagan's Star Wars". www.atomicarchive.com.

- ^ "The End of the Cold War". www.atomicarchive.com.

- ^ Masco, Joseph (2006). The nuclear borderlands: the Manhattan Project in post-Cold War New Mexico (paperback ed.). Princeton University Press. p. 78. ISBN 978-0-691-12077-5.

- ^ Majumdar, Dave (1 March 2018). "Russia's Nuclear Weapons Buildup Is Aimed at Beating U.S. Missile Defenses". The National Interest. USA.

- ^ "What's the arms race? A short history". USA Today.

- ^ "Trump's call for an 'arms race' flabbergasts nuclear experts". NBC News. 23 December 2016.

- ^ Pilkington, Ed; Pengelly, Martin (2016-12-24). "'Let it be an arms race': Donald Trump appears to double down on nuclear expansion". The Guardian.

- ^ Ellyatt, Holly (22 October 2018). "Gorbachev says Trump's nuclear treaty withdrawal 'not the work of a great mind'". CNBC.

- ^ Swanson, Ian (27 October 2018). "Trump stokes debate about new Cold War arms race". The Hill.

- ^ "Russia warns about nuclear war possibility". www.aa.com.tr.

- ^ Xia, Lili; Robock, Alan; Scherrer, Kim; Harrison, Cheryl S.; Bodirsky, Benjamin Leon; Weindl, Isabelle; Jägermeyr, Jonas; Bardeen, Charles G.; Toon, Owen B.; Heneghan, Ryan (15 August 2022). "Global food insecurity and famine from reduced crop, marine fishery and livestock production due to climate disruption from nuclear war soot injection". Nature Food. 3 (8): 586–596. doi:10.1038/s43016-022-00573-0. hdl:11250/3039288. PMID 37118594. S2CID 251601831.

- ^ Xia et al.(2022, esp. Tables 1 and 2); 5 billion = 80% of the 6.7 billion 2010 population in the countries included in the study; the difference between the 6.7 billion included in the study and the 7 billion 2010 world population is not likely to make a substantive difference in this percentage.

- ^ Diaz-Maurin, François (20 October 2022). "Nowhere to hide: How a nuclear war would kill you — and almost everyone else". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.

- ^ "World Nuclear war between the U.S. and Russia would kill more than 5 billion people – just from starvation, study finds". CBS News. 16 August 2022.

- ^ "Putin pulls back from last remaining nuclear arms control pact with the US". CNN. 21 February 2023.

- ^ "Putin defends Ukraine invasion, warns West in address". NHK World. 21 February 2023.

- ^ "A new arms race in Europe? US long-range weapons in Germany". Deutsche Welle. 13 July 2024.

- ^ a b c "Putin warns US against deploying long-range missiles in Germany". The Guardian. 28 July 2024.

- ^ "Russia says US missiles in Germany signal return of Cold War". Al Jazeera. 11 July 2024.

- ^ "Germany split on US stationing long-range cruise missiles". Deutsche Welle. 11 July 2024.

- ^ "Thanks to Putin, the U.S. will again place long-range missiles in Germany". The Hill. 12 July 2024.

- ^ "America prepares for a new nuclear-arms race". The Economist. 12 August 2024. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 2024-08-13.

- ^ "India's Nuclear Weapons Program – Smiling Buddha: 1974". nuclearweaponarchive.org.

- ^ FIles. "1974 Nuclear files". Nuclear Age Peace Foundation. Nuclear files archives. Retrieved 14 January 2013.

- ^ "India-Pakistan nuclear war could kill 2 billion people: Study". WION. 16 August 2022.

- ^ Tania Branigan (2010-01-12). "China 'successfully tests missile interceptor'". the Guardian.

- ^ Ratliff, Ben. "India successfully tests missile interceptor". International Herald Tribune. Archived from the original on 10 March 2009. Retrieved 6 December 2012.

- ^ "Akash Missile Achieves Direct-Hit, Destroys Banshee Target". The New Indian Express. Archived from the original on November 23, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Muller, Harald (2020). "Nuclear Disarmament without the Nuclear-Weapon States: The Nuclear Weapon Ban Treaty". Daedalus. 149 (2): 171–189. doi:10.1162/daed_a_01796. S2CID 214612868.

- ^ a b c Wirtz, James (2019). "Nuclear disarmament and the end of chemical weapons 'system of restraint'". International Affairs. 95 (4): 785–799. doi:10.1093/ia/iiz108.

- ^ a b c Knopf, Jeffery (2012). "Nuclear Disarmament and Nonproliferation". International Security. 37: 92–132. doi:10.1162/ISEC_a_00109. S2CID 57570232.

References

- Boughton, G. J. (1974). Journal of Interamerican Studies and World Affairs (16th ed.). Miami, United States of America: Center for Latin American Studies at the University of Miami.

- Brown, A. Reform, Coup and Collapse: The End of the Soviet State. BBC History. Retrieved November 22, 2012

- Cold War: A Brief History. (n.d.). Atomic Archive. Retrieved November 16, 2012

- Doty, P., Carnesale, A., & Nacht, M. (1976, October). The Race to Control Nuclear Arms.

- Jones, R. W. (1998). Pakistan's Nuclear Posture: Arms Race Instabilities in South Asia.

- Joyce, A., Bates Graber, R., Hoffman, T. J., Paul Shaw, R., & Wong, Y. (1989, February). The Nuclear Arms Race: An Evolutionary Perspective.

- Maloney, S. M. (2007). Learning to love the bomb: Canada's nuclear weapons during the Cold War. Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books.

- May, E. R. (n.d.). John F Kennedy and the Cuban Missile Crisis. BBC History. Retrieved November 22, 2012

- Van, C. M. (1993). Nuclear proliferation and the future of conflict. New York, United States: Free Press.

- Lili Xia; Alan Robock; Kim J N Scherrer; et al. (15 August 2022). "Global food insecurity and famine from reduced crop, marine fishery and livestock production due to climate disruption from nuclear war soot injection". Nature Food. 3 (8): 586–596. doi:10.1038/S43016-022-00573-0. ISSN 2662-1355. Wikidata Q113732668.

Further reading

- "Presidency in the Nuclear Age", conference and forum at the JFK Library, Boston, October 12, 2009. Four panels: "The Race to Build the Bomb and the Decision to Use It", "Cuban Missile Crisis and the First Nuclear Test Ban Treaty", "The Cold War and the Nuclear Arms Race", and "Nuclear Weapons, Terrorism, and the Presidency".

External links

- Erik Ringmar, "The Recognition Game: Soviet Russia Against the West," Cooperation & Conflict, 37:2, 2002. pp. 115–136. – the arms race between the superpowers explained through the concept of recognition.

- Annotated bibliography on the nuclear arms race from the Alsos Digital Library for Nuclear Issues