Newport News Shipbuilding

Newport News Shipbuilding (NNS), a division of Huntington Ingalls Industries, is the sole designer, builder, and refueler of aircraft carriers and one of two providers of submarines for the United States Navy. Founded as the Chesapeake Dry Dock and Construction Co. in 1886, Newport News Shipbuilding has built more than 800 ships, including both naval and commercial ships. Located in the city of Newport News, Virginia, its facilities span more than 550 acres (2.2 km2).

The shipyard is a major employer, not only for the lower Virginia Peninsula, but also portions of Hampton Roads south of the James River and the harbor, portions of the Middle Peninsula region, and even some northeastern counties of North Carolina.

The shipyard is building two Gerald R. Ford-class aircraft carriers: USS John F. Kennedy (CVN-79), and USS Enterprise (CVN-80).[1][2]

In 2013, Newport News Shipbuilding began the deactivation of the first nuclear-powered aircraft carrier, USS Enterprise (CVN-65),[3] which it also built.

Newport News Shipbuilding also performs refueling and complex overhaul (RCOH) work on Nimitz-class aircraft carriers. This is a four-year vessel renewal program that not only involves refueling of the vessel's nuclear reactors but also includes modernization work. The yard has completed RCOH for five Nimitz-class carriers (USS Nimitz, USS Dwight D. Eisenhower, USS Carl Vinson, USS Theodore Roosevelt and USS Abraham Lincoln).[4] As of November 2017 this work was underway for the sixth Nimitz-class vessel, USS George Washington.[5]

History

Industrialist Collis P. Huntington (1821–1900) provided crucial funding to complete the Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad (C&O) from Richmond, Virginia, to the Ohio River in the early 1870s. Although originally built for general commerce, this C&O rail link to the midwest was soon also being used to transport bituminous coal from the previously isolated coalfields, adjacent to the New River and the Kanawha River in West Virginia. In 1881, the Peninsula Extension of the C&O was built from Richmond down the Virginia Peninsula to reach a new coal pier on Hampton Roads in Warwick County near the small unincorporated community of Newport News Point. However, building the railroad and coal pier was only the first part of Huntington's dreams for Newport News.[citation needed]

The shipyard's early years

In 1886, Huntington built a shipyard to repair ships servicing this transportation hub. In 1891 Newport News Shipbuilding and Drydock Company delivered its first ship, the tugboat Dorothy. By 1897 NNS had built three warships for the US Navy: USS Nashville, Wilmington and Helena.[citation needed]

When Collis died in 1900, his nephew Henry E. Huntington inherited much of his uncle's fortune. He also married Collis' widow Arabella Huntington, and assumed Collis' leadership role with Newport News Shipbuilding and Drydock Company. Under Henry Huntington's leadership, growth continued.[citation needed]

In 1906 the revolutionary HMS Dreadnought launched a great naval race worldwide. Between 1907 and 1923, Newport News built six of the US Navy's total of 22 dreadnoughts – USS Delaware, Texas, Pennsylvania, Mississippi, Maryland and West Virginia. All but the first were in active service in World War II. In 1907 President Theodore Roosevelt sent the Great White Fleet on its round-the-world voyage. NNS had built seven of its 16 battleships.[citation needed]

In 1914 NNS built SS Medina for the Mallory Steamship Company; as MV Doulos she was until 2009 the world's oldest active ocean-faring passenger ship.[citation needed]

Newport News and the shipyard

In the early years, leaders of the Newport News community and those of the shipyard were virtually interchangeable. Shipyard president Walter A. Post served from March 9, 1911, to February 12, 1912, when he died. Earlier, he had come to the area as one of the builders of the C&O Railway's terminals, and had served as the first mayor of Newport News after it became an independent city in 1896. It was on March 14, 1914, that Albert Lloyd Hopkins, a young New Yorker trained in engineering, succeeded Post as president of the company. In May 1915 while traveling to England on shipyard business aboard RMS Lusitania, Hopkins died when that ship was torpedoed and sunk by a German U-boat[6] off Queenstown on the Irish coast. His assistant, Frederic Gauntlett, was also on board, but was able to swim to safety.[7] Homer Lenoir Ferguson was company vice president when Hopkins died, and assumed the presidency the following August.[8] He saw the company through both world wars, became a noted community leader, and was a co-founder of the Mariners' Museum with Archer Huntington. He served until July 31, 1946, after World War II had ended on both the European and Pacific fronts.[citation needed]

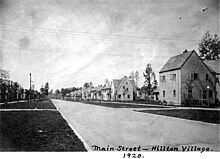

Just northwest of the shipyard, Hilton Village, one of the first planned communities in the country, was built by the federal government to house shipyard workers in 1918. The planners met with the wives of shipyard workers. Based on their input 14 house plans were designed for the projected 500 English-village-style homes. After the war, in 1922, Henry Huntington acquired it from the government, and helped facilitate the sale of the homes to shipyard employees and other local residents. Three streets there were named after Post, Hopkins, and Ferguson.[9]

Navy orders during and after World War I

The Lusitania incident was among the events that brought the United States into World War I. Between 1918 and 1920 NNS delivered 25 destroyers, and after the war it began building aircraft carriers. USS Ranger was delivered in 1934, and NNS went on to build Yorktown and Enterprise.[citation needed]

Ocean liners

After World War I NNS completed a major reconditioning and refurbishment of the ocean liner SS Leviathan. Before the war she had been the German liner Vaterland, but the start of hostilities found her laid up in New York Harbor and she had been seized by the US Government in 1917 and converted into a troopship. War duty and age meant that all wiring, plumbing, and interior layouts were stripped and redesigned while her hull was strengthened and her boilers converted from coal to oil while being refurbished. Virtually a new ship emerged from NNS in 1923, and SS Leviathan became the flagship of United States Lines.[citation needed]

In 1927 NNS launched the world's first significant turbo-electric ocean liner: Panama Pacific Line's 17,833 GRT SS California.[10] At the time she was also the largest merchant ship yet built in the United States,[10] although she was a modest size compared with the biggest European liners of her era. NNS launched California's sister ships Virginia in 1928 and Pennsylvania in 1929. NNS followed them by launching two even larger turbo-electric liners for Dollar Steamship Company: the 21,936 GRT SS President Hoover in 1930, followed by her sister President Coolidge in 1931. SS America was launched in 1939 and entered service with United States lines shortly before World War II but soon returned to the shipyard for conversion to a troopship, USS West Point.[citation needed]

Navy orders before and during World War II

By 1940 the Navy had ordered a battleship, seven more aircraft carriers and four cruisers. During World War II, NNS built ships as part of the U.S. government's Emergency Shipbuilding Program, and swiftly filled requests for "Liberty ships" that were needed during the war. It founded the North Carolina Shipbuilding Company, an emergency yard on the banks of the Cape Fear River and launched its first Liberty ship before the end of 1941, building 243 ships in all, including 186 Libertys. For its contributions during the war, the Navy awarded the company its "E" pennant for excellence in shipbuilding. NNS ranked 23rd among United States corporations in the value of wartime production contracts.[11]

Post-war ships

In the post-war years NNS built the passenger liner SS United States, which set a transatlantic speed record that still stands today. In 1954 NNS, Westinghouse and the US Navy developed and built a prototype nuclear reactor for a carrier propulsion system. NNS designed USS Enterprise in 1960. In 1959 NNS launched its first nuclear-powered submarine, USS Robert E. Lee.[citation needed]

In the 1970s, NNS launched two of the largest tankers ever built in the western hemisphere and also constructed three liquefied natural gas carriers – at over 390,000 deadweight tons, the largest ever built in the United States. NNS and Westinghouse Electric Company jointly formed Offshore Power Systems to build floating nuclear power plants for Public Service Electric and Gas Company.

In the 1980s, NNS produced a variety of Navy products, including Nimitz-class nuclear aircraft carriers and Los Angeles-class nuclear attack submarines. Since 1999 the shipyard has only produced warships for the Navy.[12]

Submarine building problems

In 2007, the US Navy found that workers had used the incorrect metal to fuse together pipes and joints on submarines under construction and this could have eventually led to cracking and leaks. In 2009 it was found that bolts and fasteners in weapons-handling systems on four Navy submarines, New Mexico, North Carolina, Missouri, and California, were installed incorrectly, delaying the launching of the boats while the problems were corrected.[13]

Mergers, realignment, and spin-off

In 1968, Newport News merged with Tenneco Corporation. In 1996, Tenneco initiated a spinoff of Newport News into an independent company (Newport News Shipbuilding).[14] In 2001, General Dynamics made a second bid to purchase the company after a failed bid in 1999.[15] Such a merger would have eliminated competition for the production of Virginia-class submarines, which have only been made by Newport News and GD subsidiary Electric Boat. Northrop Grumman matched GD with a similar bid, and following a Department of Justice anti-trust lawsuit to block GD's bid, GD called off their bid.[16] Now as the sole bidder, Northrop Grumman purchased the company for $2.6 billion and renamed it "Northrop Grumman Newport News".[17] This division was merged with Northrop Grumman Ship Systems in 2008 and given the name "Northrop Grumman Shipbuilding".[18] Three years later, the company was spun off as Huntington Ingalls Industries, Inc.,[19] which trades under the symbol HII on the New York Stock Exchange.[citation needed]

Presidents

- Matt Mulherin (2011-2017)[20]

- Jennifer Boykin (2017–present)[21]

Ships built

- Dorothy

Other ships built at the Newport News yard include:[citation needed]

- Gerald R. Ford-class nuclear-powered aircraft carriers:

- USS Enterprise (CVN-80), under construction

- USS Doris Miller (CVN-81), under construction

- Liberty ship transports for the Allies during World War II

- Los Angeles-class nuclear-powered submarines

- Virginia-class nuclear-powered submarines

Gallery

- Ronald Reagan Christening

- North Yard Crane

- Newport News Shipbuilding Foundry & Switch Engine

Ships rebuilt

- SS Jacona, the first sea-going electric power plant for emergencies[citation needed]

- Sea Witch, wrecked ship that was salvaged and her still-operational stern and machinery spaces rebuilt and used in the construction of a new chemical tanker, the Chemical Discoverer, later renamed Chemical Pioneer[citation needed]

World War II Shipbuilding Facilities

| Shipway | Width | Length | Type | Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 76 feet (23 m)[24] | 628 feet (191 m)[24] | Inclined Slipway | |

| 3 | 76 feet (23 m)[24] | 628 feet (191 m)[24] | Inclined Slipway | |

| 4 | 76 feet (23 m)[24] | 628 feet (191 m)[24] | Inclined Slipway | |

| 5 | 76 feet (23 m)[24] | 628 feet (191 m)[24] | Inclined Slipway | |

| 6 | 96 feet (29 m)[24] | 628 feet (191 m)[24] | Inclined Slipway | |

| 7 | 76 feet (23 m)[24] | 628 feet (191 m)[24] | Inclined Slipway | |

| 8 | 111 feet (34 m)[25] | 1,000 feet (300 m)[25] | Semi-submerged Inclined Slipway | 1919 |

| 9 | 111 feet (34 m)[25] | 1,000 feet (300 m)[25] | Semi-submerged Inclined Slipway | 1919 |

| 10 | 128 feet (39 m)[26] | 960 feet (290 m)[26] | Graving Dock | 1941 |

| 11 | 140 feet (43 m)[26] | 1,100 feet (340 m)[26] | Graving Dock | 1941 |

References

- ^ "Enterprise (CVN 80) Advanced Planning Contract Awarded". Archived from the original on August 6, 2017. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- ^ "HII gets additional $228m for Enterprise (CVN-80) long lead time materials". navaltoday.com. December 28, 2018. Retrieved March 26, 2019.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "HII Awarded $745 Million Contract to Inactivate USS Enterprise (CVN 65)". Archived from the original on April 26, 2015. Retrieved June 28, 2013.

- ^ "Refueling and Complex Overhaul (RCOH)". Newport News Shipbuilding. Huntington Ingalls Industries, Inc. Archived from the original on May 1, 2016. Retrieved June 4, 2016.

- ^ USS George Washington CVN73 arrives for RCOH Archived May 13, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, Newport News Shipbuilding, Access date May 10, 2018

- ^ "Mr. Albert Lloyd Hopkins". Saloon (First Class) Passenger List. The Lusitania Resource. July 25, 2011. Archived from the original on April 27, 2012. Retrieved December 5, 2012.

- ^ Ruegsegger, Bob. "Authenticity Regs & More". Great War Association. Archived from the original on February 20, 2012. Retrieved December 5, 2012.

- ^ "Ferguson Becomes Head of Shipbuilding Plant". Richmond Times-Dispatch. Richmond, Virginia. August 13, 1915. p. 10. Archived from the original on August 13, 2015. Retrieved August 13, 2015.

- ^ "Hilton Village 1969 Nomination Form, p2-3" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places Inventory. US Department of the Interior. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 27, 2012. Retrieved December 5, 2012.

- ^ a b "Panama Pacific Lines finished". Time. Michael L Grace. May 9, 1938. Archived from the original on May 20, 2013. Retrieved May 19, 2013.

- ^ Peck, Merton J; Scherer, Frederic M (1962). The Weapons Acquisition Process: An Economic Analysis. Boston, MA: Harvard Business Press. p. 619.

- ^ "Ships Built By Newport News Shipbuilding" (PDF). Huntington-Ingalls. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 7, 2017. Retrieved July 16, 2018.

- ^ Frost, Peter, "Northrop Moving Forward On Submarine Investigation", Newport News Daily Press, September 30, 2009.

- ^ "Our Heritage". Archived from the original on March 16, 2010. Retrieved February 18, 2009.

- ^ "Shipbuilding deal floated". CNN Money. Retrieved February 11, 2024.

- ^ "General Dynamics calls off Newport bid". CNN Money. Archived from the original on June 24, 2023. Retrieved February 11, 2024.

- ^ "Northrop to buy Newport News for $2.6B – Nov. 8, 2001". Archived from the original on June 6, 2011.

- ^ "Photo Release -- Northrop Grumman Announces Key Leadership and Organizational Changes". Archived from the original on February 19, 2008. Retrieved February 5, 2008.

- ^ America's Largest Military Shipbuilder Begins Operations as a New, Publicly Traded Company Under the Name of Huntington Ingalls Industries Archived May 30, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Newport News Shipbuilding president Matt Mulherin to retire". The Virginian-Pilot. Archived from the original on April 9, 2021. Retrieved April 8, 2021.

- ^ "The Power List - Jennifer Boykin, president, Newport News Shipbuilding". Inside Business. Archived from the original on March 3, 2021. Retrieved April 8, 2021.

- ^ "Abel P. Upshur (Destroyer No. 193)". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Naval History and Heritage Command. February 23, 2016. Archived from the original on September 6, 2019. Retrieved September 11, 2019.

Abel P. Upshur (Destroyer No. 193) was laid down on 20 August 1918 at Newport News, Va., by the Newport News Shipbuilding & Drydock Co.; launched on 14 February 1920; sponsored by Mrs. George J. Benson, great-great niece of Secretary Upshur

- ^ "Pacific marine review".

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l A Statistical Summary of Shipbuilding Under the U. S. Maritime Commission During World War II. U.S. Government Printing Office. 1949. p. 94. ISBN 9780598775030. Archived from the original on June 24, 2023. Retrieved March 19, 2023.

- ^ a b c d National Defense Migration: Washington, D. C., hearings, March 24-26, 1941. pt.12. San Diego, June 12-13, 1941. U.S. Government Printing Office. 1941. p. 4468. Archived from the original on June 24, 2023. Retrieved March 19, 2023.

- ^ a b c d The Ports of Hampton Roads, Virginia. U.S. Government Printing Office. 1949. p. 229. Archived from the original on June 24, 2023. Retrieved March 19, 2023.