Infidel

An infidel (literally "unfaithful") is a person who is accused of disbelief in the central tenets of one's own religion, such as members of another religion, or irreligious people.[1][2]

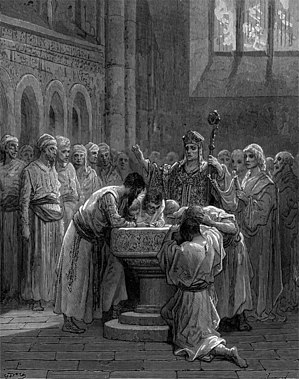

Infidel is an ecclesiastical term in Christianity around which the Church developed a body of theology that deals with the concept of infidelity, which makes a clear differentiation between those who were baptized and followed the teachings of the Church versus those who are outside the faith.[3] Christians used the term infidel to describe those perceived as the enemies of Christianity.

After the ancient world, the concept of otherness, an exclusionary notion of the outside by societies with more or less coherent cultural boundaries, became associated with the development of the monotheistic and prophetic religions of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam (cf. pagan).[3]

In modern literature, the term infidel includes in its scope atheists,[4][5][6] polytheists,[7] animists,[8] heathens, and pagans.[9]

A willingness to identify other religious people as infidels corresponds to a preference for orthodoxy over pluralism.[10]

Etymology

The origins of the word infidel date to the late 15th century, deriving from the French infidèle or Latin īnfidēlis, from in- "not" + fidēlis "faithful" (from fidēs "faith", related to fīdere 'to trust'). The word originally denoted a person of a religion other than one's own, especially a Christian to a Muslim, a Muslim to a Christian, or a gentile to a Jew.[2] Later meanings in the 15th century include "unbelieving", "a non-Christian" and "one who does not believe in religion" (1527).

Usage

Christians historically used the term infidel to refer to people who actively opposed Christianity. This term became well-established in English by sometime in the early sixteenth century, when Jews or Muslims were described contemptuously as active opponents to Christianity. In Catholic dogma, an infidel is one who does not believe in the doctrine at all and is thus distinct from a heretic, who has fallen away from true doctrine, i.e. by denying the divinity of Jesus. Similarly, the ecclesiastical term was also used by the Methodist Church,[11][12] in reference to those "without faith".[13]

Today, the usage of the term infidel has declined;[14] the current preference is for the terms non-Christians and non-believers (persons without religious affiliations or beliefs), reflecting the commitment of mainstream Christian denominations to engage in dialog with persons of other faiths.[15] Nevertheless, some apologists have argued in favor of the term, stating that it does not come from a disrespectful perspective, but is similar to using the term orthodox for devout believers.[16]

Moreover, some translations of the Bible, including the King James Version, which is still in vogue today, employ the word infidel, while others have supplanted the term with nonbeliever. The term is found in two places:

And what concord hath Christ with Belial? Or what part hath he that believeth with an infidel? —2 Corinthians 6:15 KJV

But if any provide not for his own, and specially for those of his own house, he hath denied the faith, and is worse than an infidel. —1 Timothy 5:8 KJV

Infidels under Catholic Canon Law

Right to rule

In Quod super his, Innocent IV asked the question, "[I]s it licit to invade a land that infidels possess or which belongs to them?" and held that while Infidels had a right to dominium (right to rule themselves and choose their own governments), the pope, as the Vicar of Christ, de jure possessed the care of their souls and had the right to politically intervene in their affairs if their ruler violated or allowed his subjects to violate a Christian and Euro-centric normative conception of Natural law, such as sexual perversion or idolatry.[17] He also held that he had an obligation to send missionaries to infidel lands, and that if they were prevented from entering or preaching, then the pope was justified in dispatching Christian forces accompanied with missionaries to invade those lands, as Innocent stated simply: "If the infidels do not obey, they ought to be compelled by the secular arm and war may be declared upon them by the pope, and nobody else."[18] This was however not a reciprocal right and non-Christian missionaries such as those of Muslims could not be allowed to preach in Europe "because they are in error and we are on a righteous path."[17]

A long line of Papal hierocratic canonists, most notably those who adhered to Alanus Anglicus's influential arguments of the Crusading-era, denied Infidel dominium, and asserted Rome's universal jurisdictional authority over the earth, as well as the right to authorize pagan conquests solely on the basis of non-belief because of their rejection of the Christian God.[19] In the extreme, the hierocractic canonical discourse of the mid-twelfth century, such as that espoused by Bernard of Clairvaux, the mystic leader of the Cisertcians, legitimized German colonial expansion and practice of forceful Christianisation in the Slavic territories as a holy war against the Wends, arguing that infidels should be killed wherever they posed a menace to Christians. When Frederick the II unilaterally arrogated papal authority, he took on the mantle to "destroy convert, and subjugate all barbarian nations," a power in papal doctrine reserved for the pope. Hostiensis, a student of Innocent, in accord with Alanus, also asserted "... by law infidels should be subject to the faithful." John Wyclif, regarded as the forefather of English Reformation, also held that valid dominium rested on a state of grace.[20]

The Teutonic Knights were one of the by-products of this papal hierocratic and German discourse. After the Crusades in the Levant, they moved to crusading activities in the infidel Baltics. Their crusades against the Lithuanians and Poles, however, precipitated the Lithuanian Controversy, and the Council of Constance, following the condemnation of Wyclif, found Hostiensis's views no longer acceptable and ruled against the knights. Future Church doctrine was then firmly aligned with Innocents IV's position.[21]

The later development of counterarguments on the validity of Papal authority, the rights of infidels, and the primacy of natural law led to various treatises such as those by Hugo Grotius, John Locke, Immanuel Kant and Thomas Hobbes.

Colonization of the Americas

During the Age of Discovery, papal bulls such as Romanus Pontifex and, more importantly, inter caetera (1493), implicitly removed dominium from infidels and granted them to the Spanish Empire and Portugal with the charter of guaranteeing the safety of missionaries. Subsequent rejections of the bull by Protestant powers rejected the Pope's authority to exclude other Christian princes. As independent authorities, they drew up charters for their own colonial missions based on the temporal right for care of infidel souls in language echoing the inter caetera. The charters and papal bulls would form the legal basis of future negotiations and consideration of claims as title deeds in the emerging law of nations during the period of European colonization.[22]

The rights bestowed by Romanus Pontifex and inter caetera have never fallen from use, serving as the basis for legal arguments over the centuries. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in the 1823 case Johnson v. McIntosh that as a result of European discovery and assumption of ultimate dominion, Native Americans had only a right to occupancy of native lands, not the right of title. In the 1831 case Cherokee Nation v. Georgia, famously described Native American tribes as "domestic dependent nations." In Worcester v. Georgia, the court ruled that the Native Tribes were sovereign entities to the extent that the U.S. federal government, and not individual states, had authority over their affairs.

Native American groups including the Taíno and Onondaga have called on the Vatican to revoke the bulls of 1452, 1453, and 1493.[citation needed]

Marriage

According to the Catholic Encyclopedia, the Catholic Church views marriage as forbidden and null when conducted between the faithful (Christians) and infidels, unless a dispensation has been granted. This is because marriage is a sacrament of the Catholic Church, which infidels are deemed incapable of receiving.[23]

As a philosophical tradition

Some philosophers such as Thomas Paine, David Hume, George Holyoake, Charles Bradlaugh, Voltaire and Rousseau earned the label of infidel or freethinkers, both personally and for their respective traditions of thought because of their attacks on religion and opposition to the Church. They established and participated in a distinctly labeled, infidel movement or tradition of thought, that sought to reform their societies which were steeped in Christian thought, practice, laws and culture. The Infidel tradition was distinct from parallel anti-Christian, sceptic or deist movements, in that it was anti-theistic and also synonymous with atheism. These traditions also sought to set up various independent model communities, as well as societies, whose traditions then gave rise to various other socio-political movements such as secularism in 1851, as well as developing close philosophical ties to some contemporary political movements such as socialism and the French Revolution.[24]

Towards the early twentieth century, these movements sought to move away from the tag "infidel" because of its associated negative connotation in Christian thought, and there is attributed to George Holyoake the coining of the term 'secularism' in an attempt to bridge the gap with other theist and Christian liberal reform movements.[24]

In 1793, Immanuel Kant's Religion within the Boundaries of Mere Reason, reflected the Enlightenment periods' philosophical development, one which differentiated between the moral and rational and substituted rational/irrational for the original true believer/infidel distinction.[3]

Implications for medieval civil law

Laws passed by the Catholic Church governed not just the laws between Christians and infidels in matters of religious affairs, but also civil affairs. They were prohibited from participating or aiding in infidel religious rites, such as circumcisions or wearing images of non-Christian religious significance.[23]

In the Early Middle Ages, based on the idea of the superiority of Christians to infidels, regulations came into place such as those forbidding Jews from possessing Christian slaves; the laws of the decretals further forbade Christians from entering the service of Jews, for Christian women to act as their nurses or midwives; forbidding Christians from employing Jewish physicians when ill; restricting Jews to definite quarters of the towns into which they were admitted and to wear a dress by which they might be recognized.[23]

Later during the Victorian era, testimony of either self-declared, or those accused of being Infidels or Atheists, was not accepted in a court of law because it was felt that they had no moral imperative to not lie under oath because they did not believe in God, or Heaven and Hell.[24]

These rules have now given way to modern legislation and Catholics, in civil life, are no longer governed by ecclesiastical law.[23]

Analogous terms in other religions

Islam

One Arabic language analogue to infidel, referring to non-Muslims, is kafir (sometimes "kaafir", "kufr" or "kuffar") from the root K-F-R, which connotes covering or concealing.[25][26] The term KFR may also refer to disbelieve in something, ungrateful for something provided or denunciation of a certain matter or life style.[27] Another term, sometimes used synonymously, is mushrik, "polytheist" or "conspirer", which more immediately connotes the worship of gods other than Allah.[28][29]

In the Quran, the term kafir is first applied to the unbelieving Meccans, and their attempts to refute and revile Muhammad. Later, Muslims are ordered to keep apart from them and defend themselves from their attacks.[30][31]

In the Quran the term "people of the book" (Ahl al-Kitāb) refers to Jews, Christians, and Sabians.[32] In this way, Islam considers Jews and Christians as followers of scriptures sent by God previously.[33][34] The term people of the book was later expanded to include adherents of Zoroastrianism and Hinduism by Islamic rulers in Persia and India.[35]

In some verses of the Quran, particularly those recited after the Hijra in AD 622, the concept of kafir was expanded upon, with Jews for disbelief in God's sign and killing prophets like Jesus and Christians for believing the trinity and that Jesus was the son of God, which the Quran considers it to be idolatry.[30][36][page needed][37][38][39][page needed]

Some hadiths prohibit declaring a Muslim to be a kafir, but the term was nonetheless fairly frequent in the internal religious polemics of the age.[31] For example, some texts of the Sunni sect of Islam include other sects of Islam such as Shia as infidel.[40] Certain sects of Islam, such as Wahhabism, include as kafir those Muslims who undertake Sufi shrine pilgrimage and follow Shia teachings about Imams.[41][42][43][page needed] Similarly, in Africa and South Asia, certain sects of Islam such as Hausas, Ahmadi, Akhbaris have been repeatedly declared as Kufir or infidels by other sects of Muslims.[44][45][46]

The class of kafir also includes the category of murtadd, variously translated as apostate or renegades, for whom classical jurisprudence prescribes death if they refuse to return to Islam.[31] On the subject of ritual impurity of unbelievers, one finds a range of opinions, "from the strictest to the most tolerant", in classical jurisprudence.[31]

Historically, the attitude toward unbelievers in Islam was determined more by socio-political conditions than by religious doctrine. A tolerance toward unbelievers prevailed even to the time of the Crusades, particularly with respect to the People of the Book. However, animosity was nourished by repeated wars with unbelievers, and warfare between Safavid Persia and Ottoman Turkey brought about application of the term kafir even to Persians in Turkish fatwas.[31]

In Sufism the term underwent a special development, as in a well-known verse of Abu Sa'id: "So long as belief and unbelief are not perfectly equal, no man can be a true Muslim", which has prompted various explanations.[31]

Judaism

Judaism has a notion of pagan gentiles who are called עכו״ם 'acum, an acronym of Ovdei Cohavim u-Mazzaloth or, literally, "star-and-constellation worshippers".[3][47][48]

The Hebrew term, kofer, cognate with the Arabic kafir, is reserved only for apostate Jews.[3]

See also

- Agnosticism

- Antitheism

- Apostasy

- Atheism

- Blasphemy

- Deism

- Freethought

- Infidel: My Life (autobiography)

- Kafir

- Paganism

Notes

- ^ See:

- James Ginther (2009), The Westminster Handbook to Medieval Theology, Westminster, ISBN 978-0664223977, Quote = "Infidel literally means unfaithful";

- "Infidel", The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition, Houghton Mifflin Company. "An unbeliever with respect to a particular religion, especially Christianity or Islam";

- Infidel, Oxford Dictionaries, US (2011); Quote = "A person who does not believe in religion or who adheres to a religion other than one’s own"

- ^ a b "infidel". The Oxford Pocket Dictionary of Current English. Oxford University Press. 2009. Retrieved 20 June 2010.

a person who does not believe in religion or who adheres to a religion other than one's own.

- ^ a b c d e ""Infidels." International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences. 2008". MacMillan Library Reference. Retrieved 20 June 2010.

- ^ The Works of Thomas Jackson, Volume IV. Oxford University Press. 1844. p. 5. Retrieved 8 April 2011.

Atheism and irreligion are diseases so much more dangerous than infidelity or idolatry, as infidelity than heresy. Every heretic is in part an infidel, but every infidel is not in whole or part an heretic; every atheist is an infidel, so is not every infidel an atheist.

- ^ The Bengal Annual. Samuel Smith and Co. 1830. p. 209. Retrieved 8 April 2011.

Kafir means an infidel, but more properly an atheist.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church. Burns & Oates. 23 June 2002. ISBN 9780860123248. Retrieved 8 April 2011.

2123 'Many... of our contemporaries either do not at all perceive, or explicitly reject, this intimate and vital bond of man to God. Atheism must therefore be regarded as one of the most serious problems of our time.' 2125 Since it rejects or deniest the existence of God, atheism is a sin against the virtue of religion.

- ^ See:

- Ken Ward (2008), in Expressing Islam: Religious Life and Politics in Indonesia, Editors: Greg Fealy, Sally White, ISBN 978-9812308511, Chapter 12;

- Alexander Ignatenko, Words and Deeds, Russia in Global Affairs, Vol. 7, No. 2, April–June 2009, p. 145

- ^ Whitlark & Aycock (Editors) (1992), The literature of emigration and exile, Texas Tech University Press, ISBN 978-0896722637, pp. 3–28

- ^ See:

- Tibi, Bassam (2007). Political Islam, World Politics and Europe. Taylor & Francis. p. 47. ISBN 978-0415437806.

- Mignolo W. (2000), The many faces of cosmopolis: Border thinking and critical cosmopolitanism. Public Culture, 12(3), pp. 721–48

- ^ See:

- Cole & Hammond (1974), Religious pluralism, legal development, and societal complexity: rudimentary forms of civil religion, Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, Vol. 13, No. 2, pp. 177–89;

- Sullivan K. M. (1992), Religion and liberal democracy, The University of Chicago Law Review, Vol. 59, No. 1, pp. 195–223.

- ^ The Wesleyan-Methodist magazine: A Dialogue between a Believer and an Infidel. Oxford University. 1812. Retrieved 25 March 2007.

- ^ The Methodist review, Volume 89. Phillips & Hunt. 1907. Retrieved 25 March 2007.

Is it conceivable that a Spirit which is invisible, and imponderable, and impalpable, and yet which is the seat of physical and moral powers, really occupies the universe? The infidel scoffs at the idea. We observe, however, that this same infidel implicitly believes in the existence of an all-pervading luminiferous ether, which is invisible, and imponderable, and impalpable, and yet is said to be more compact and more elastic than any material substance we can see and handle.

- ^ The Primitive Methodist magazine. William Lister. 1867. Retrieved 25 March 2007.

It is sometimes translated infidels, because an infidel is without faith; but is also properly rendered unbelievers in the strict Gospel sense of the word.

- ^ Infidels. Random House. 2005. p. 197. ISBN 9780812972399. Retrieved 25 March 2007.

Likewise, "infidel," which had still been in use in the early nineteenth century, fell out of favor with hymn writers.

- ^ Russell B. Shaw, Peter M. J. Stravinskas, Our Sunday Visitor's Catholic Encyclopedia, Our Sunday Visitor Publishing, 1998, ISBN 0-87973-669-0 p. 535.

- ^ Infidel Testimony. J.E. Dixon. 1835. p. 188. Retrieved 25 March 2007.

When we use the word infidel, we intend nothing disrespectful, any more than we do when we use the word orthodox.

- ^ a b Williams, p.48

- ^ Williams, p. 14

- ^ Williams, pp. 41, 61–64

- ^ Williams, pp. 61–64

- ^ Williams, pp. 64–67

- ^ Christopher 31-40

- ^ a b c d "Catholic Encyclopedia: Infidels". Newadvent.org. 1 October 1910. Retrieved 22 August 2014.

- ^ a b c Royle, Edwards, "Victorian Infidels: The Origins of the British Secularist Movement 1791–1866", Manchester University Press, ISBN 0-7190-0557-4

- ^ Ruthven M. (2002), International Affairs, Vol. 78, No. 2, pp. 339–51

- ^ "Kaffir", The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition, Houghton Mifflin Company, 2006. "Islam An infidel."; Also: "Kaffir" - Arabic kāfir "unbeliever, infidel", Encarta World English Dictionary [North American Edition], Microsoft Corporation, 2007.

- ^ "Wiktionary". wiktionary.com.

- ^ "Encyclopædia Britannica". Britannica.com. Retrieved 22 August 2014.

- ^ Islamic Science University of Malaysia, Dr. Abdullah al-Faqih, The meaning of "Kufr" and "Shirk"

- ^ a b Campo, Juan Eduardo (2009). Encyclopedia of Islam. Infobase Publishing, New York, ISBN 978-0-8160-5454-1, see p. 421.

- ^ a b c d e f Björkman, W., "Kafir". E. J. Brill's First Encyclopaedia of Islam, 1913–1936, Volume 4, ISBN 9789004097902; pp. 619–20

- ^ Vajda, G (2012). "Ahl al-Kitāb". In P. Bearman; Th. Bianquis; C.E. Bosworth; E. van Donzel; W.P. Heinrichs (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam. Vol. 1 (2nd ed.). Brill. p. 264. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_SIM_0383.

- ^ "Infidel" in An Introductory Dictionary of Theology and Religious Studies, p. 630

- ^ "Kafir" in An Introductory Dictionary of Theology and Religious Studies p. 702

- ^ Noegel, Scott B.; Wheeler, Brannon M. (2010). The A to Z of Prophets in Islam and Judaism. Scarecrow Press. p. 249. ISBN 9781461718956.

People of the Book. Term used in the Quran and in Muslim sources for Jews and Christians, but also exteneded to include Sabians, Zoroastrians, Hindus, and others.

- ^ Lewis, Bernard. The political language of Islam. University of Chicago Press, 1991.

- ^ Waldman, Marilyn Robinson. "The Development of the Concept of Kufr in the Qur'ān." Journal of the American Oriental society 88.3 (1968): 442–55.

- ^ "Ayah/Ayat". Oxford Islamic Studies. Oxford University. Archived from the original on 19 February 2013. Retrieved 9 January 2019.

- ^ Schimmel, Annemarie, and Abdoldjavad Falaturi. We Believe in One God: The Experience of God in Christianity and Islam. Seabury Press, 1979.

- ^ Wilfred Madelung (1970), Early Sunnī Doctrine concerning Faith as Reflected in the" Kitāb al-Īmān", Studia Islamica, No. 32, pp. 233–54

- ^ Williams, Brian Glyn. "Jihad and ethnicity in post‐communist Eurasia. on the trail of transnational islamic holy warriors in Kashmir, Afghanistan, Central Asia, Chechnya and Kosovo." The Global Review of Ethnopolitics 2.3–4 (2003): 3–24.

- ^ Ungureanu, Daniel. "Wahhabism, Salafism and the Expansion of Islamic Fundamentalist Ideology." Journal of the Seminar of Discursive Logic, Argumentation Theory and Rhetoric. 2011.

- ^ Marshall, Paul A., ed. Radical Islam's Rules: The Worldwide Spread of Extreme Shariʻa Law. Rowman & Littlefield, 2005.

- ^ Mark Juergensmeyer (2011), The Oxford Handbook of Global Religions, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0199767649, pp. 451, 519–23

- ^ Patrick J. Ryan, Ariadne auf Naxos: Islam and Politics in a Religiously Pluralistic African Society, Journal of Religion in Africa, Vol. 26, Fasc. 3 (Aug., 1996), pp. 308–29

- ^ H. R. Palmer, An Early Fulani Conception of Islam, Journal of the Royal African Society, Vol. 13, No. 52, pp. 407–14

- ^ Walter Zanger, "Jewish Worship, Pagan Symbols: Zodiac mosaics in ancient synagogues", Bible History Daily; first published 24 August 2012, updated 24 August 2014.

- ^ Shay Zucker, "Hebrew Names of the Planets", The Role of Astronomy in Society and Culture, Proceedings of the International Astronomical Union, IAU Symposium, Volume 260; p. 302.

References

- Williams, Robert A. The American Indian in Western Legal Thought: The Discourses of Conquest, 1990, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-508002-5

- Tomlins, Christopher L.; Mann, Bruce H. The Many Legalities of Early America, 2001, UNC Press, ISBN 0-8078-4964-2

- Weckman, George. The Language of the Study of Religion: A Handbook, 2001, Xlibris Corporation ISBN 0-7388-5105-1[self-published source]

- Merriam-Webster's Dictionary of Synonyms, Merriam-Webster Inc., 1984, ISBN 0-87779-341-7

- Espin, Orlando O.; Nickoloff, James B. An Introductory Dictionary of Theology and Religious Studies, Liturgical Press, 2007, ISBN 0-8146-5856-3

- Attribution

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Infidels". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Infidels". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

External links

- Prayer of St. Francis Xavier for the Conversion of the Infidels: a prayer written by Francis Xavier, Doctor of the Church

- Definition of "infidel" by the Merriam-Webster dictionary

- Definition of "unbeliever" by the Merriam-Webster dictionary

- Infidels: a history of the conflict between Christendom and Islam by Andrew Wheatcroft Random house, 2005