Nineteenth-century theatre

A wide range of movements existed in the theatrical culture of Europe and the United States in the 19th century. In the West, they include Romanticism, melodrama, the well-made plays of Scribe and Sardou, the farces of Feydeau, the problem plays of Naturalism and Realism, Wagner's operatic Gesamtkunstwerk, Gilbert and Sullivan's plays and operas, Wilde's drawing-room comedies, Symbolism, and proto-Expressionism in the late works of August Strindberg and Henrik Ibsen.[1]

Melodrama

Beginning in France after the theatre monopolies were abolished during the French Revolution, melodrama became the most popular theatrical form of the century. Melodrama itself can be traced back to classical Greece, but the term mélodrame did not appear until 1766 and only entered popular usage sometime after 1800. The plays of August von Kotzebue and René Charles Guilbert de Pixérécourt established melodrama as the dominant dramatic form of the early 19th century.[2] Kotzebue in particular was the most popular playwright of his time, writing more than 215 plays that were produced all around the world. His play The Stranger (1789) is often considered the classic melodramatic play. Although monopolies and subsidies were reinstated under Napoleon, theatrical melodrama continued to be more popular and brought in larger audiences than the state-sponsored drama and operas.

Melodrama involved a plethora of scenic effects, an intensely emotional but codified acting style, and a developing stage technology that advanced the arts of theatre towards grandly spectacular staging. It was also a highly reactive form of theatre which was constantly changing and adapting to new social contexts, new audiences and new cultural influences. This, in part, helps to explains its popularity throughout the 19th century.[3] David Grimsted, in his book Melodrama Unveiled (1968), argues that:

Its conventions were false, its language stilted and commonplace, its characters stereotypes, and its morality and theology gross simplifications. Yet its appeal was great and understandable. It took the lives of common people seriously and paid much respect to their superior purity and wisdom. [...] And its moral parable struggled to reconcile social fears and life's awesomeness with the period's confidence in absolute moral standards, man's upward progress, and a benevolent providence that insured the triumph of the pure.[4]

In Paris, the 19th century saw a flourishing of melodrama in the many theatres that were located on the popular Boulevard du Crime, especially in the Gaîté. All this was to come to an end, however, when most of these theatres were demolished during the rebuilding of Paris by Baron Haussmann in 1862.[5]

By the end of the 19th century, the term melodrama had nearly exclusively narrowed down to a specific genre of salon entertainment: more or less rhythmically spoken words (often poetry)—not sung, sometimes more or less enacted, at least with some dramatic structure or plot—synchronized to an accompaniment of music (usually piano). It was looked down on as a genre for authors and composers of lesser stature (probably also the reason why virtually no realisations of the genre are still remembered).

Romanticism in Germany and France

In Germany, there was a trend toward historical accuracy in costumes and settings, a revolution in theatre architecture, and the introduction of the theatrical form of German Romanticism. Influenced by trends in 20th -century philosophy and the visual arts, German writers were increasingly fascinated with their Teutonic past and had a growing sense of romantic nationalism. The plays of Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Friedrich Schiller, and other Sturm und Drang playwrights, inspired a growing faith in feeling and instinct as guides to moral behavior. Romantics borrowed from the philosophy of Immanuel Kant to formulate the theoretical basis of "Romantic" art. According to Romantics, art is of enormous significance because it gives eternal truths a concrete, material form that the limited human sensory apparatus may apprehend. Among those who called themselves Romantics during this period, August Wilhelm Schlegel and Ludwig Tieck were the most deeply concerned with theatre.[6] After a time, Romanticism was adopted in France with the plays of Victor Hugo, Alexandre Dumas, Alfred de Musset, and George Sand.

Through the 1830s in France, the theatre struggled against the Comédie-Française, which maintained a strong neo-classical hold over the repertory and encouraged traditional modes of tragic writing in new playwrights. This clash culminated in the premiere of Hernani by Victor Hugo in 1830. The large crowd that attended the premiere was full of conservatives and censors who booed the show for disobeying the classical norms and who wanted to stop the performance from going forward. But Hugo organized a Romantic Army of bohemian and radical writers to ensure that the opening would have to go ahead. The resulting riot represented the rejection in France of the classical traditions and the triumph of Romanticism.[7]

By the 1840s, however, enthusiasm for Romantic drama had faded in France and a new "Theatre of Common Sense" replaced it.

Well-made play

In France, the "well-made play" of Eugene Scribe (1791–1861) became popular with playwrights and audiences. First developed by Scribe in 1825, the form has a strong Neoclassical flavour, involving a tight plot and a climax that takes place close to the end of the play. The story depends upon a key piece of information kept from some characters, but known to others (and to the audience). A recurrent device that the well-made play employs is the use of letters or papers falling into unintended hands, to bring about plot twists and climaxes. The suspense and pace builds towards a climactic scene, in which the hero triumphs in an unforeseen reversal of fortune.[8]

Scribe himself wrote over 400 plays of this type, using what essentially amounted to a literary factory with writers who supplied the story, another the dialogue, a third the jokes and so on. Although he was highly prolific and popular, he was not without detractors: Théophile Gautier questioned how it could be that, "an author without poetry, lyricism, style, philosophy, truth or naturalism could be the most successful writer of his epoch, despite the opposition of literature and the critics?"[9]

Its structure was employed by realist playwrights Alexandre Dumas, fils, Emile Augier, and Victorien Sardou. Sardou in particular was one of the world's most popular playwrights between 1860 and 1900. He adapted the well-made play to every dramatic type, from comedies to historical spectacles. In Britain, playwrights like Wilkie Collins, Henry Arthur Jones and Arthur Pinero took up the genre, with Collins describing the well-made play as: "Make 'em laugh; make 'em weep; make 'em wait." George Bernard Shaw thought that Sardou's plays epitomized the decadence and mindlessness into which the late 19th-century theatre had descended, a state that he labeled "Sardoodledom".[8]

Theatre in Britain

In the early years of the 19th century, the Licensing Act allowed plays to be shown at only two theatres in London during the winter: Drury Lane and Covent Garden. These two huge theatres contained two royal boxes, huge galleries, and a pit with benches where people could come and go during performances. Perhaps the most telling episode of the popularity of theatre in the early 19th century is the theatrical Old Price riots of 1809. After Covent Garden burned down, John Philip Kemble, the theatre's manager, decided to raise prices in the pit, the boxes and the third tier. Audience members hated the new pricing which they thought denied them access to a national meeting place and led to three months of rioting until finally Kemble was forced to publicly apologize and lower prices again.[10] To escape the restrictions, non-patent theatres along the Strand, like the Sans Pareil, interspersed dramatic scenes with musical interludes and comic skits after the Lord Chamberlain's Office allowed them to stage Burlettas—leading to the formation of the modern West End. Outside of the metropolitan area of London, theatres like Astley's Amphitheatre and the Coburg were also able to operate outside of the rules. The exploding popularity of these forms began to make the patent system unworkable and the boundaries between the two began to blur through the 1830s until finally the Licensing Act was dropped in 1843 with the Theatres Act. Parliament hoped that this would civilize the audiences and lead to more literate playwrighting—instead, it created an explosion of Music halls, comedies and sensationalist melodramas.[11]

Percy Bysshe Shelley and Lord Byron were the most important literary dramatists of their time (although Shelley's plays were not performed until later in the century). Shakespeare was enormously popular, and began to be performed with texts closer to the original, as the drastic rewriting of 17th and 18th century performing versions for the theatre were gradually removed over the first half of the century. Kotzebue's plays were translated into English and Thomas Holcroft's A Tale of Mystery was the first of many English melodramas. Pierce Egan, Douglas William Jerrold, Edward Fitzball, James Roland MacLaren and John Baldwin Buckstone initiated a trend towards more contemporary and rural stories in preference to the usual historical or fantastical melodramas. James Sheridan Knowles and Edward Bulwer-Lytton established a "gentlemanly" drama that began to re-establish the former prestige of the theatre with the aristocracy.[12]

Theatres throughout the century were dominated by actor-managers who managed the establishments and often acted in the lead roles. Henry Irving, Charles Kean and Herbert Beerbohm Tree are all examples of managers who created productions in which they were the star performer. Irving especially dominated the Lyceum Theatre for almost 30 years from 1871 to 1899 and was hero-worshipped by his audiences. When he died in 1905, King Edward VII and Theodore Roosevelt send their condolences. Among these actor-managers, Shakespeare was often the most popular writer as his plays afforded them great dramatic opportunity and name recognition. The stage spectacle of these productions was often more important than the play and texts were often cut to give maximum exposure to the leading roles. However, they also introduced significant reforms into the theatrical process. For example, William Charles Macready was the first to introduce proper rehearsals to the process. Before this lead actors would rarely rehearse their parts with the rest of the cast: Edmund Kean's most famous direction to his fellow actors being, "stand upstage of me and do your worst."[10]

Melodramas, light comedies, operas, Shakespeare and classic English drama, pantomimes, translations of French farces and, from the 1860s, French operettas, continued to be popular, together with Victorian burlesque. The most successful dramatists were James Planché and Dion Boucicault, whose penchant for making the latest scientific inventions important elements in his plots exerted considerable influence on theatrical production. His first big success, London Assurance (1841) was a comedy in the style of Sheridan, but he wrote in various styles, including melodrama. T. W. Robertson wrote popular domestic comedies and introduced a more naturalistic style of acting and stagecraft to the British stage in the 1860s.

In 1871, the producer John Hollingshead brought together the librettist W.S. Gilbert and the composer Arthur Sullivan to create a Christmas entertainment, unwittingly spawning one of the great duos of theatrical history. So successful were the 14 comic operas of Gilbert and Sullivan, such as H.M.S. Pinafore (1878) and The Mikado (1885), that they had a huge influence over the development of musical theatre in the 20th century.[13] This, together with much improved street lighting and transportation in London and New York led to a late Victorian and Edwardian theatre building boom in the West End and on Broadway. At the end of the century, Edwardian musical comedy came to dominate the musical stage.[14]

In the 1890s, the comedies of Oscar Wilde and George Bernard Shaw offered sophisticated social comment and were very popular.

Theatre in the United States

In the United States, Philadelphia was the dominant theatrical centre until the 1820s. There, Thomas Wignell established the Chestnut Street Theatre and gathered a group of actors and playwrights that included William Warren, Susanna Rowson, and Thomas Abthorpe Cooper, who later was considered the leading actor in North America. In its infancy after the American Revolution, many Americans lamented the lack of a 'native drama', even while playwrights such as Royall Tyler, William Dunlap, James Nelson Barker, John Howard Payne, and Samuel Woodworth laid the foundations for an American drama separate from Britain. Part of the reason for the dearth of original plays in this period may be that playwrights were rarely paid for their work and it was much cheaper for managers to adapt or translate foreign work. Tradition held that remuneration was mainly in the form of a benefit performance for the writer on the third night of a run, but many managers would skirt this custom by simply closing the show before the third performance.[15]

Known as the "Father of the American Drama", Dunlap grew up watching plays given by British officers and was heavily immersed in theatrical culture while living in London just after the Revolution. As the manager of the John Street Theatre and Park Theatre in New York City, he brought back to his country the plays and theatrical values that he had seen. Like many playwright-managers of his day, Dunlap adapted or translated melodramatic works by French of German playwrights, but he also wrote some 29 original works including The Father (1789), André (1798), and The Italian Father (1799).[16]

From 1820 to 1830, improvements in the material conditions of American life and the growing demand of a rising middle class for entertainment led to the construction of new theatres in New York, Philadelphia, Boston and Washington, including Chatham Garden, Federal Street, the Tremont, Niblo's Garden and the Bowery. During the early part of this period, Philadelphia continued to be the major theatrical centre: plays would often open in Baltimore in September or October before transferring to larger theatres in Philadelphia until April or May, followed by a summer season in Washington or Alexandria. However, rivalries and larger economic forces led to a string of bankruptcies for five major theatre companies in just eight months between 1 October 1828 and 27 May 1829. Due to this and the import of star system performers like Clara Fisher, New York took over as the dominant city in American theatre.[15]

In the 1830s, Romanticism flourished in Europe and America with writers like Robert Montgomery Bird rising to the forefront. Since Romanticism emphasized eternal truths and nationalistic themes, it fit perfectly with the emerging national identity of the United States. Bird's The Gladiator was well-received when it premiered in 1831 and was performed at Drury Lane in London in 1836 with Edwin Forrest as Spartacus, with The Courier proclaiming that "America has at length vindicated her capability of producing a dramatist of the highest order." Dealing with slave insurgency in Ancient Rome, The Gladiator implicitly attacks the institution of Slavery in the United States by "transforming the Antebellum into neoclassical rebels".[17] Forrest would continue to play the role for over one thousand performances around the world until 1872. Following the success of their early collaboration, Bird and Forrest would work together on further premieres of Oralloosa, Son of the Incas and The Broker of Bogota. But the success of The Gladiator led to contract disagreements, with Bird arguing that Forrest, who had made tens of thousands from Bird's plays, owed him more than the $2,000 he had been paid.

Minstrel shows emerged as brief burlesques and comic Entr'actes in the early 1830s. They were developed into full-fledged form in the next decade. By 1848, blackface minstrel shows were the national art form, translating formal art such as opera into popular terms for a general audience. Each show consisted of comic skits, variety acts, dancing, and music performances that mocked people specifically of African descent. The shows were performed by Caucasians in make-up or blackface for the purpose of playing the role of black people. Minstrel songs and sketches featured several Stock characters, most popularly the slave and the dandy. These were further divided into sub-archetypes such as the mammy, her counterpart the old darky, the provocative mulatto wench, and the black soldier. Minstrels claimed that their songs and dances were authentically black, although the extent of the black influence remains debated.

Star actors amassed an immensely loyal following, comparable to modern celebrities or sports stars. At the same time, audiences had always treated theaters as places to make their feelings known, not just towards the actors, but towards their fellow theatergoers of different classes or political persuasions, and theatre Riots were a regular occurrence in New York.[18] An example of the power of these stars is the Astor Place riot in 1849, which was caused by a conflict between the American star Edwin Forrest and the English actor William Charles Macready. The riot pitted immigrants and nativists against each other, leaving at least 25 dead and more than 120 injured.

In the pre-Civil War era, there were also many types of more political drama staged across the United States. As America pushed west in the 1830s and 40s, theatres began to stage plays that romanticized and masked treatment of Native Americans like Pocahontas, The Pawnee Chief, De Soto and Metamora or the Last of the Wampanoags. Some fifty of these plays were produced between 1825 and 1860, including burlesque performances of the "noble savage" by John Brougham.[19] Reacting off of current events, many playwrights wrote short comedies that dealt with the major issues of the day. For example, Removing the Deposits was a farce produced in 1835 at the Bowery in reaction to Andrew Jackson's battle with the banks and Whigs and Democrats, or Love of No Politics was a play that dealt with the struggle between America's two political parties.

In 1852, Harriet Beecher Stowe published the anti-slavery novel Uncle Tom's Cabin and, without any strong copyright laws, was immediately dramatized on stages across the country. At the National Theatre in New York, it was a huge success and ran for over two hundred performances up to twelve times per week until 1854. The adaptation by George Aiken was a six-act production that stood on its own, without any other entertainments or afterpiece.[20] Minstrelsy's reaction to Uncle Tom's Cabin is indicative of plantation content at the time. Tom acts largely came to replace other plantation narratives, particularly in the third act. These sketches sometimes supported Stowe's novel, but just as often they turned it on its head or attacked the author. Whatever the intended message, it was usually lost in the joyous, slapstick atmosphere of the piece. Characters such as Simon Legree sometimes disappeared, and the title was frequently changed to something more cheerful like "Happy Uncle Tom" or "Uncle Dad's Cabin". Uncle Tom himself was frequently portrayed as a harmless bootlicker to be ridiculed. Troupes known as Tommer companies specialized in such burlesques, and theatrical Tom shows integrated elements of the minstrel show and competed with it for a time.

After the Civil War, the American stage was dominated by melodramas, minstrel shows, comedies, farces, circuses, vaudevilles, burlesques, operas, operettas, musicals, musical revues, medicine shows, amusement arcades, and Wild West shows. Many American playwrights and theatre workers lamented the "failure of the American playwright", including Augustin Daly, Edward Harrigan, Dion Boucicault, and Bronson Howard. However, as cities and urban areas boomed from immigration in the late nineteenth century, the social upheaval and innovation in technology, communication and transportation had a profound effect on the American theatre.[21]

In Boston, although ostracized from Gilded Age society, Irish American performers began to find success, including Lawrence Barrett, James O'Neill, Dan Emmett, Tony Hart, Annie Yeamans, John McCullough, George M. Cohan, and Laurette Taylor, and Irish playwrights came to dominate the stage, including Daly, Harrigan, and James Herne.[22]

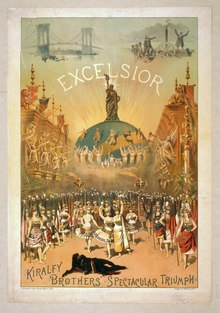

In 1883, the Kiralfy brothers met with Thomas Edison at Menlo Park to see if the electric light bulb could be incorporated into a musical ballet called Excelsior that they were to present at Niblo's Gardens in New York City. A showman himself, Edison realized the potential of this venture to create demand for his invention, and together they designed a finale to the production that would be illuminated by more than five hundred light bulbs attached to the costumes of the dancers and to the scenery. When the show opened on 21 August, it was an immediate hit, and would subsequently be staged in Buffalo, Chicago, Denver and San Francisco. Thus, electric lighting in the theatre was born and would radically change not just stage lighting, but the principles of scenic design.[22]

The Gilded Age was also the golden age of touring in American theatre: while New York City was the mecca of the ambitious, the talented and the lucky, throughout the rest of the country, a network of theatres large and small supported a huge industry of famous stars, small troupes, minstrel shows, vaudevillians, and circuses. For example, in 1895, the Burt Theatre in Toledo, Ohio offered popular melodramas for up to thirty cents a seat and saw an average audience of 45,000 people per month at 488 performances of 64 different plays. On average 250–300 shows, many originating in New York, crisscrossed the country each year between 1880 and 1910. Meanwhile, owners of successful theatres began to expand their reach, like the theatrical empire of B.F. Keith and Edward F. Albee that spanned over seven hundred theatres, including the Palace in New York.[23] This culminated in the founding of the Theatre Syndicate in 1896.

New York City's importance as a theatrical center grew in the 1870s around Union Square until it became the primary theatre center, and the Theater District slowly moved north from lower Manhattan until it finally arrived in midtown at the end of the century.

On the musical stage, Harrigan and Hart innovated with comic musical plays from the 1870s, but London imports came to dominate, beginning with Victorian burlesque, then Gilbert and Sullivan from 1880, and finally (in competition with George M. Cohan and musicals by the Gershwins) Edwardian musical comedies at the turn of the century and into the 1920s.[14]

Meiningen Ensemble and Richard Wagner

In Germany, drama entered a state of decline from which it did not recover until the 1890s. The major playwrights of the period were Otto Ludwig and Gustav Freytag. The lack of new dramatists was not keenly felt because the plays of Shakespeare, Lessing, Goethe, and Schiller were prominent in the repertory. The most important theatrical force in later 19th-century Germany was that of Georg II, Duke of Saxe-Meiningen and his Meiningen Ensemble, under the direction of Ludwig Chronegk. The Ensemble's productions are often considered the most historically accurate of the 19th century, although his primary goal was to serve the interests of the playwright. The Ensemble's productions used detailed, historically accurate costumes and furniture, something that was unprecedented in Europe at the time. The Meiningen Ensemble stands at the beginning of the new movement toward unified production (or what Richard Wagner would call the Gesamtkunstwerk) and the rise of the director (at the expense of the actor) as the dominant artist in theatre-making.[24]

The Meiningen Ensemble traveled throughout Europe from 1874 to 1890 and met with unparalleled success wherever they went. Audiences had grown tired with regular, shallow entertainment theatre and were beginning to demand a more creatively and intellectually stimulating form of expression that the Ensemble was able to provide. Therefore, the Meiningen Ensemble can be seen as the forerunners of the art-theatre movement which appeared in Europe at the end of the 1880s.[25]

Richard Wagner (1813–1883) rejected the contemporary trend toward realism and argued that the dramatist should be a myth maker who portrays an ideal world through the expression of inner impulses and aspirations of a people. Wagner used music to defeat performers' personal whims. The melody and tempo of music allowed him to have greater personal control over performance than he would with spoken drama. As with the Meininger Ensemble, Wagner believed that the author-composer should supervise every aspect of production to unify all the elements into a "master art work."[26] Wagner also introduced a new type of auditorium that abolished the side boxes, pits, and galleries that were a prominent feature of most European theatres and replaced them with a 1,745 seat fan-shaped auditorium that was 50 feet (15 m) wide at the proscenium and 115 feet (35 m) at the rear. This allowed every seat in the auditorium to enjoy a full view of the stage and meant that there were no "good" seats.

Rise of realism in Russia

In Russia, Aleksandr Griboyedov, Alexander Pushkin, and Nikolai Polevoy were the most accomplished playwrights. As elsewhere, Russia was dominated by melodrama and musical theatre. More realistic drama began to emerge with the plays of Nikolai Gogol and the acting of Mikhail Shchepkin. Under close government supervision, the Russian theatre expanded considerably. Prince Alexander Shakhovskoy opened state theatres and training schools, attempted to raise the level of Russian production after a trip to Paris, and put in place regulations for governing troupes that remained in effect until 1917.[27]

Realism began earlier in the 19th century in Russia than elsewhere in Europe and took a more uncompromising form.[28] Beginning with the plays of Ivan Turgenev (who used "domestic detail to reveal inner turmoil"), Aleksandr Ostrovsky (who was Russia's first professional playwright), Aleksey Pisemsky (whose A Bitter Fate (1859) anticipated Naturalism), and Leo Tolstoy (whose The Power of Darkness (1886) is "one of the most effective of naturalistic plays"), a tradition of psychological realism in Russia culminated with the establishment of the Moscow Art Theatre by Konstantin Stanislavski and Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko.[29]

Ostrovsky is often credited with creating a peculiarly Russian drama. His plays Enough Stupidity in Every Wise Man (1868) and The Storm (1859) draw on the life that he knew best, that of the middle class. Other important Russian playwrights of the 19th century include Alexander Sukhovo-Kobylin (whose Tarelkin's Death (1869) anticipated the Theatre of the Absurd) and Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin.

Naturalism and Realism

Naturalism, a theatrical movement born out of Charles Darwin's The Origin of Species (1859) and contemporary political and economic conditions, found its main proponent in Émile Zola. His essay "Naturalism in the Theatre" (1881) argued that poetry is everywhere instead of in the past or abstraction: "There is more poetry in the little apartment of a bourgeois than in all the empty worm-eaten palaces of history."

The realisation of Zola's ideas was hindered by a lack of capable dramatists writing naturalist drama. André Antoine emerged in the 1880s with his Théâtre Libre that was only open to members and therefore was exempt from censorship. He quickly won the approval of Zola and began to stage Naturalistic works and other foreign realistic pieces. Antoine was unique in his set design as he built sets with the "fourth wall" intact, only deciding which wall to remove later. The most important French playwrights of this period were given first hearing by Antoine including Georges Porto-Riche, François de Curel, and Eugène Brieux.[30]

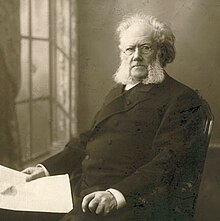

The work of Henry Arthur Jones and Arthur Wing Pinero initiated a new direction on the English stage. While their work paved the way, the development of more significant drama owes itself most to the playwright Henrik Ibsen.

Ibsen was born in Norway in 1828. He wrote 25 plays, the most famous of which are A Doll's House (1879), Ghosts (1881), The Wild Duck (1884), and Hedda Gabler (1890). A Doll's House and Ghosts shocked conservatives: Nora's departure in A Doll's House was viewed as an attack on family and home, while the allusions to venereal disease and sexual misconduct in Ghosts were considered deeply offensive to standards of public decency. Ibsen refined Scribe's well-made play formula to make it more fitting to the realistic style. He provided a model for writers of the realistic school. In addition, his works Rosmersholm (1886) and When We Dead Awaken (1899) evoke a sense of mysterious forces at work in human destiny, which was to be a major theme of symbolism and the so-called "Theatre of the Absurd".

After Ibsen, British theatre experienced revitalization with the work of George Bernard Shaw, Oscar Wilde, and (in fact from 1900) John Galsworthy. Unlike most of the gloomy and intensely serious work of their contemporaries, Shaw and Wilde wrote primarily in the comic form.

Technological Changes

Stage lighting

The eighteenth century theatre had been lit by candles and oil-lamps which were mainly provided for illumination so that the audience could see the performance, with no further purpose. This changed in the early 19th century with the introduction of gas lighting which was slowly adopted by the major theatres throughout the 1810s and 1820s to provide illumination for the house and the stage. The introduction of gas lighting revolutionized stage lighting. It provided a somewhat more natural and adequate light for the playing and the scenic space upstage of the proscenium arch. While there was no way to control the gas lights, this was soon to change as well. In Britain, theatres in London developed limelight for the stage in the late 1830s. In Paris, the electric carbon arc lamp first came into use in the 1840s. Both of these types of lighting were able to be hand-operated and could be focused by means of an attached lens, thus giving the theatre an ability to focus light on particular performers for the first time.[31]

From the 1880s onwards, theatres began to be gradually electrified with the Savoy Theatre becoming the first theatre in the world to introduce a fully electrified theatrical lighting system in 1881. Richard D'Oyly Carte, who built the Savoy, explained why he had introduced electric light: "The greatest drawbacks to the enjoyment of the theatrical performances are, undoubtedly, the foul air and heat which pervade all theatres. As everyone knows, each gas-burner consumes as much oxygen as many people, and causes great heat beside. The incandescent lamps consume no oxygen, and cause no perceptible heat."[32] Notably, the introduction of electric light coincided with the rise of realism: the new forms of lighting encouraged more realistic scenic detail and a subtler, more realistic acting style.[33]

Scenic design

One of the most important scenic transition into the century was from the often-used two-dimensional scenic backdrop to three-dimensional sets. Previously, as a two-dimensional environment, scenery did not provide an embracing, physical environment for the dramatic action happening on stage. This changed when three-dimensional sets were introduced in the first half of the century. This, coupled with change in audience and stage dynamic as well as advancement in theatre architecture that allowed for hidden scene changes, the theatre became more representational instead of presentational, and invited audience to be transported to a conceived 'other' world. The early 19th century also saw the innovation of the moving panorama: a setting painted on a long cloth, which could be unrolled across the stage by turning spools, created an illusion of movement and changing locales.[34]

See also

References

- ^ Brockett and Hildy (2003, 293–426).

- ^ Brockett and Hildy (2003, 277).

- ^ Booth (1995, 300).

- ^ Grimsted (1968, 248).

- ^ The golden age of the Boulevard du Crime Theatre online.com (in French)

- ^ Brockett and Hildy (2003, 278–280).

- ^ Booth, Michael R (1995). Nineteenth-century Theatre. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 308.

- ^ a b Encyclopædia Britannica Editors. "well-made play". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 1 November 2015.

- ^ Gautier, Histoire de l'art dramatique en France (1859), cited in Cardwell (1983), p. 876.

- ^ a b 19th century theatre. Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved 1 November 2015.

- ^ Bratton, Jacky (15 March 2014). "Theatre in the 19th century". Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- ^ Brockett and Hildy (2003, 297–298).

- ^ Brockett and Hildy (2003, 326–327).

- ^ a b The first "Edwardian musical comedy" is usually considered to be In Town (1892). See, e.g., Charlton, Fraser. "What are EdMusComs?" FrasrWeb 2007, accessed 12 May 2011

- ^ a b Quinn, Arthur Hobson (1923). History of the American Drama: From the Beginning to the Civil War. Harper & Brothers. p. 203.

- ^ Quinn, Arthur Hobson (1923). History of the American Drama: from the Beginning to the Civil War. Harper & Brothers. p. 161.

- ^ Reed, Peter. "Slave Revolt and Classical Blackness in The Gladiator". Rogue Performances: Staging the Underclasses in Early American Theatre Culture: 151.

- ^ Burrows, Edwin G. & Wallace, Mike (1999). Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 761. ISBN 0-195-11634-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Quinn, Arthur Hobson (1923). History of the American Drama. Harper & Brothers. p. 275.

- ^ Wilmeth, Don B. (1998). Staging the Nation: Plays from the American Theater, 1787–1909. Boston: Bedford Books. p. 181.

- ^ Postlewait, Thomas (1999). Wilmeth, Don B.; Bigsby, Christopher (eds.). The Cambridge History of American Theatre, Volume II, 1870–1945. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. p. 147.

- ^ a b Postlewait, Thomas (1999). Wilmeth, Don B.; Bigsby, Christopher (eds.). The Cambridge History of American Theatre, Volume II, 1870–1945. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. pp. 128–137. ISBN 0-521-65179-4.

- ^ Postlewait (1999, 154–157)

- ^ Brockett and Hildy (2003, 357–359).

- ^ Fischer-Lichte (2001, 245)

- ^ Brockett and Hildy (2003, 378).

- ^ Brockett and Hildy (2003, 293).

- ^ Brockett and Hildy (2003, 370).

- ^ Brockett and Hildy (2003, 370, 372) and Benedetti (2005, 100) and (1999, 14–17).

- ^ Brockett and Hildy (2003, 362–363).

- ^ Booth (1995, 302)

- ^ Baily, p. 215

- ^ Booth (1995, 303)

- ^ Baugh (2005, 11–33)

Sources

- 19th-century theatre. Victoria and Albert Museum, 2015. Web. 1 November 2015.

- Baily, Leslie (1956). The Gilbert and Sullivan Book (fourth ed.). London: Cassell. OCLC 21934871.

- Banham, Martin, ed. 1998. The Cambridge Guide to Theatre. Cambridge: Cambridge UP. ISBN 0-521-43437-8.

- Baugh, Christopher (2005). Theatre, Performance and Technology. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Benedetti, Jean. 1999. Stanislavski: His Life and Art. Revised edition. Original edition published in 1988. London: Methuen. ISBN 0-413-52520-1.

- ---. 2005. The Art of the Actor: The Essential History of Acting, From Classical Times to the Present Day. London: Methuen. ISBN 0-413-77336-1.

- Booth, Michael R. 1995. 'Nineteenth-Century Theatre'. In John Russell Brown. 1995. The Oxford Illustrated History of Theatre. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-212997-X.

- Brockett, Oscar G. and Franklin J. Hildy. 2003. History of the Theatre. Ninth edition, International edition. Boston: Allyn and Bacon. ISBN 0-205-41050-2.

- Cardwell, Douglas (May 1983). "The Well-Made Play of Eugène Scribe". American Association of Teachers of French 56 (6): 878–879. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

- Fischer-Lichte, Erika. 2001. History of European Drama and Theatre. New York: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 0-415-18059-7.

- Grimsted, David. 1968. Melodrama Unveiled: American Theatre and Culture, 1800–50. Chicago: U of Chicago P. ISBN 978-0-226-30901-9.

- "well-made play". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, 2015. Web. 1 November 2015.

- Stephenson, Laura, et al. (2013). Forgotten Comedies of the 19th Century Theater. Clarion Publishing, Staunton, Va.. ISBN 978-1492881025.