Nicolas Minorsky

Nicolas Minorsky | |

|---|---|

Nikolai Fyodorovich Minorsky | |

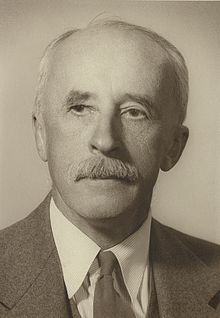

Minorsky, c. 1955 | |

| Born | 23 September 1885 |

| Died | 31 July 1970 (aged 84) Italy |

| Alma mater | |

| Known for | Non-linear Control Theory |

| Awards | Montyon Prize (1955) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Mathematics, Engineering |

| Institutions | |

| Thesis | Electronic conduction and ionization in crossed electric and magnetic fields (1929) |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | Imperial Russian Navy |

| Years of service | 1908–1918 |

| Rank | Lieutenant |

Nicolas Minorsky (born Nikolai Fyodorovich Minorsky, Russian: Николай Федорович Минорский; 23 September [O.S. 11 September] 1885 – 31 July 1970) was a Russian American control theory mathematician, engineer[1] and applied scientist. He is best known for his theoretical analysis and first proposed application of PID controllers in the automatic steering systems for U.S. Navy ships.[2]

Career

Nicolas Minorsky was born on 23 September [O.S. 11 September] 1885 in Korcheva, Tver, northwest of Moscow on the upper Volga River, a town now submerged beneath the Ivankovo Reservoir. He was educated at the Nikolaev Maritime Academy in St. Petersburg, graduating in 1908 and commissioned as a lieutenant in the Imperial Russian Navy. From 1908 to 1911, he studied in the Electrical Engineering Department at the University of Nancy, graduating with the degree Ingénieur Électricien. In 1912, he received his licence ès sciences from the University of Nancy. He then returned to St. Petersburg and studied at the Imperator's Petersburg Institute of Technology, receiving a degree in Electro-Mechanical Engineering in 1914. After graduating he served in the fleet from 1914 to 1916. From 1916 to 1917, Minorsky was Superintendent of gyro-compasses and lecturer on gyroscopic phenomena and applications at the Nikolaev Maritime Academy. While there he invented the gyrometer, an angular velocity indicator, and in tests compared it to the human eye's sensitivity in detecting angular velocities.[3]

He was the adjunct Naval Attache at the Russian Embassy to France in Paris from 1917 to 1918. In the midst of the Russian Civil War Minorsky emigrated to the United States in June 1918.[2]

From 1918 to 1922, Minorsky worked as an assistant to C. P. Steinmetz at the General Electric Research Laboratory in Schenectady, New York.[2] In 1922, Minorsky helped in the installation and testing of automatic steering on board the battleship USS New Mexico. In relation to this work Minorsky authored a paper introducing the concept of Integral and Derivative Control.[4] This paper is one of the earliest formal discussions on control theory in the English language.[2] Today, this analysis is considered pioneering and fundamental to control theory as work by James Clerk Maxwell, Edward John Routh, and Adolf Hurwitz.[3]

From 1924 to 1934, Nicolas Minorsky was a Professor of Electronics and Applied Physics at the University of Pennsylvania.[2] He received his Ph.D. in physics from Penn in 1929.[5]

Upon request of the United States Department of the Navy, the National Academy of Sciences established a committee chaired by William F. Durand to investigate anti-rolling devices on ships. The ability to stabilize a ship such as an aircraft carrier would be extremely useful during the landing of airplanes. The committee established an experimental laboratory at the Brooklyn Navy Yard.[6] Minorsky worked on roll stabilization of ships for the navy from 1934 to 1940, and in 1938 he designed an activated-tank stabilization system into a 5-ton model ship.[7] A full-scale version of the system was tested on the USS Hamilton, but it exhibited control stability problems. Promising results were beginning to appear when the outbreak of the Second World War interrupted further development as the Hamilton was called to active duty and the 5-ton model was put into storage.[6][7] At this time Minorsky took an interest in nonlinear mechanics.[2]

From 1940 to 1946, he was a special consultant to the Director of the David Taylor Model Basin, continuing his investigations of active ship stabilization and anti-submarine warfare.[2] He then moved to California in 1946, joining the Division of Engineering Mechanics at Stanford University, where he continued his work on ship stabilization. The 5-ton model was moved from the David Taylor Model Basin to Stanford where it was dubbed the "USS Minorsky".[2][7] Full-scale testing of active ship stabilization system resumed, this time on board the USS Peregrine.[7]

In her memorial paper to Nicolas Minorsky published in the IEEE Transactions On Automatic Control, author Irmgard Flügge-Lotz stated that Minorsky's greatest contribution to the development of nonlinear mechanics in the U.S. was Minorsky's early recognition that important papers in the field were being published in the Soviet Union in a language that few American researchers could read.[2] In 1947, Minorsky published a book of new Russian developments titled "Introduction to non-linear mechanics: Topological methods, analytical methods, non-linear resonance, relaxation oscillations".

After retirement Nicolas Minorsky and his French-born wife, Madeline (Palisse) moved to southern France and settled in the foothills of the Pyrenees.[2] Minorsky continued to work, giving seminars and lectures in Europe, authoring theoretical papers until the end of his life in 1970.[2]

Awards

1955 Montyon Prize of the French Academy of Science.[2]

Bibliography

A list of selected works:

Books

- Minorsky, N. (1947). Introduction to non-linear mechanics: Topological methods, analytical methods, non-linear resonance, relaxation oscillations. J.W. Edwards. ISBN 978-93-336-9885-6.

- Minorsky, N. (1958). Dynamics and Nonlinear Mechanics: The Theory of Oscillations. Surveys in Applied Mathematics. Wiley. pp. 110–206. ISBN 978-1-124-15874-7.

- Minorsky, N. (1962). Nonlinear Oscillations. D. Van Nostrand Company, Inc., Princenton, New Jersey. pp. 714.

- Minorsky, N. (April 1962). G. Szego; et al. (eds.). On some aspects of non-linear oscillations. Studies in Mathematical Analysis and Related Topics. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-0140-2.

Papers

- Minorsky, N. (1922). "Directional stability of automatically steered bodies". Journal of the American Society of Naval Engineers. 34 (2): 280–309. doi:10.1111/j.1559-3584.1922.tb04958.x.

- Minorsky, N. (1927). "Phenomenon of direct-current self excitation in vacuum tubes circuits and in applications". J. Franklin Inst. 203 (Feb): 181–209. doi:10.1016/S0016-0032(27)92437-5.

- Minorsky, N. (1930). "Automatic steering test". J. Amer. Soc. Nav. Eng. 42.

- Minorsky, N. (1934). "Ship stabilization by activated tank: An experimental investigation". Engineer (Aug).

- Minorsky, N. (1937). "The principles and practice of automatic control". Engineer. 9 (Mar).

- Minorsky, N. (1941). "Note on the angular motion of ships". J. Appl. Mech. 45 (Sep).

- Minorsky, N. (1941). "Control Problems". J. Franklin Inst. 232 (Nov. and Dec): 451–487, 519–551. doi:10.1016/s0016-0032(41)90178-3.

- Minorsky, N. (1942). "Self-excited in dynamical systems possessing retarded actions". J. Appl. Mech. 9 (June).

- Minorsky, N. (1944). "On mechanical self-excited oscillations". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 30 (Oct): 308–314. Bibcode:1944PNAS...30..308M. doi:10.1073/pnas.30.10.308. PMC 1078718. PMID 16578134.

- Minorsky, N. (1944). "On non-linear phenomenon of self-rolling". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 31 (Nov): 346–349. Bibcode:1945PNAS...31..346M. doi:10.1073/pnas.31.11.346. PMC 1078842. PMID 16578177.

- Minorsky, N. (1945). "On parametric excitation". J. Franklin Inst. 240 (July): 25–46. doi:10.1016/0016-0032(45)90217-1.

- Minorsky, N. (1947). "A dynamical analogue". J. Franklin Inst. 243 (Feb): 131–149. doi:10.1016/0016-0032(74)90312-3.

- Minorsky, N. (1947). "Experiments with activated tanks". Trans. ASME. 69 (Oct): 735.

- Minorsky, N. (1948). "Self-excited mechanical oscillations". J. Appl. Phys. 19 (Apr): 332–338. Bibcode:1948JAP....19..332M. doi:10.1063/1.1715068.

- Minorsky, N. (1951). "Modern nonlinear trends in engineering". Appl. Mech. Rev. (Mar).

- Minorsky, N. (1952). "Stationary solutions of certain nonlinear differential equations". J. Franklin Inst. 254 (Jul): 21–42. doi:10.1016/0016-0032(52)90003-3.

- Minorsky, N. (1953). "On interaction of non-linear oscillations". J. Franklin Inst. 256 (Aug): 147–165. doi:10.1016/0016-0032(53)90941-7.

- Minorsky, N. (1955). "On synchronous actions". J. Franklin Inst. 259 (Mar): 209–219. doi:10.1016/0016-0032(55)90825-5.

- Minorsky, N. (1960). "Theoretical aspects of nonlinear oscillations". IRE Trans. Circuit Theory. CT-7 (Dec): 368–381. doi:10.1109/TCT.1960.1086717.

Patents

- A US patent 1306552 A, N. Minorsky, "Gyrometer", published 1919-06-10, assigned to The Sperry Gyroscope company

- A US patent 1372184 A, N. Minorsky, "Angular-velocity-indicating apparatus", published 1921-03-22, assigned to N. Minorsky

References

- ^ Petitgirard, Loïc (2015), "L'ingénieur Nicolas Minorsky (1885–1970) et les mathématiques pour l'ingénierie navale, la théorie du contrôle et les oscillations non linéaires" [The engineer Nicolas Minorsky (1885-1970) and mathematics for naval engineering, control theory, and nonlinear oscillations], Revue d'histoire des mathématiques, Série Chaire Jean Morlet (in French), 21 (2): 173–216.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Flügge-Lotz, I. (1971). "Memorial to N. Minorsky". IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control. 16 (4). IEEE: 289–291. doi:10.1109/TAC.1971.1099734.

- ^ a b Bennett, Stuart (November 1984). "Nicholas Minorsky and the automatic steering of ships" (PDF). Control Systems Magazine. 4 (4). IEEE: 10–15. doi:10.1109/MCS.1984.1104827. S2CID 8135803. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-10-24. Retrieved 2017-09-05.

- ^ Minorsky, Nicolas (May 1922). "Directional stability of automatically steered bodies" (PDF). Journal of the American Society of Naval Engineers. 34 (2): 280–309. doi:10.1111/j.1559-3584.1922.tb04958.x. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-09-05. Retrieved 2017-09-05.

- ^ Minorsky, Nicholas (1929). Electronic conduction and ionization in crossed electric and magnetic fields (Ph.D.thesis). University of Pennsylvania. OCLC 244991706. Retrieved 15 December 2013.

- ^ a b Durand, William (1953). Adventures; In the Navy, In Education, Science, Engineering, and in War; A Life Story. American Society of Mechanical Engineers, and McGraw-Hill. p. 153. ASIN B0000CIPMH.

- ^ a b c d "Ship Stabilizer: Navy Is Testing Tank Device To Reduce Craft's Roll". New York Times. 25 June 1950.