Nasr (deity)

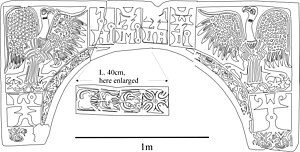

Nasr (Arabic: نسر "Vulture") was apparently a pre-Islamic Arabian deity of the Himyarites.[1] Reliefs depicting vultures have been found in Himyar, including at Maṣna'at Māriya and Haddat Gulays,[2] and Nasr appears in theophoric names.[3][4] Nasr has been identified by some scholars with Maren-Shamash,[3][5] who is often flanked by vultures in depictions at Hatra.[6] Hisham ibn Al-Kalbi's Book of Idols describes a temple to Nasr at Balkha, an otherwise unknown location.[7] Some sources attribute the deity to "the dhū-l-Khila tribe of Himyar".[8][9][10][11] Himyaritic inscriptions were thought to describe "the vulture of the east" and "the vulture of the west", which Augustus Henry Keane interpreted as solstitial worship;[12] however these are now thought to read "eastward" and "westward" with n-s-r as a preposition.[1][a] J. Spencer Trimingham believed Nasr was "a symbol of the sun".[15]

| Part of the myth series on Religions of the ancient Near East |

| Pre-Islamic Arabian deities |

|---|

| Arabian deities of other Semitic origins |

Classical references

Nasr is mentioned in the Qur'an (71:23) as an idol at the time of the Noah:

"وقالوا لا تذرن آلهتكم ولا تذرن ودا ولا سواعا ولا يغوث ويعوق ونسرا

And they say: Forsake not your gods, nor forsake Wadd, nor Suwāʿ, nor Yaghūth and Yaʿūq and Nasr."[Quran 71:23]

An Arabian vulture-god is mentioned by other ancient texts, including the Babylonian Talmud (Avodah Zarah 11b):

Ḥanan b. Ḥisda says that Abba b. Aybo says, and some say it was Ḥanan b. Rava who said that Abba b. Aybo says, "There are five permanent idolatrous temples: the temple of Bel in Babylon, the temple of Nebo in Borsippa[b], the temple of Atargatis in Manbij, the temple of Serapis[c] in Ashkelon, and the temple of Nishra[d] in Arabia".[18]

And the Doctrine of Addai:

Who is this Nebo, an idol made which ye worship, and Bel, which ye honor?[e] Behold, there are those among you who adore Bath Nical, as the inhabitants of Harran your neighbours, and Atargatis, as the people of Manbij, and Nishra,[f] as the Arabians; also the sun and the moon, as the rest of the inhabitants of Harran, who are as yourselves.[20][3]

A further mention is found in Jacob of Serugh's On the Fall of the Idols, wherein the Persians are said to have been led by the devil to construct and worship N-s-r.[3][1]

Notes

- ^ In a separate challenge to the theory of solstitial worship, Ḥisda relays that Ḥanan b. Rava interpreted Abba b. Aybo's claim that the temple was permanent (v.i.) to mean "constantly worshipped for the entire year."[13] This is accepted by Shlomo b. Yiṣḥaq, who notes, "permanent -- all year, for every day of the year would their worshippers make a festival and bring sacrifices".[14]

- ^ Printings and some MSS read כורסי Kursi, a scatological quip (Kursi resembles both the Aramaic בורסי\ף Borsippa and the Biblical Hebrew קורס squat). Borsippa's name is the butt of several Talmudic jokes; it is also called Bolsippa (as in, Balal S'fas jumbled the language of)[16] and Bor Shapi Empty Pit.[17]

- ^ Aramaic: צריפא (hapax). The reading Serapis is supported by:

- Shaick, Ronit Palistrant. "Who is Standing Above the Lions in Ascalon?". Israel Numismatic Research, 7, 2012.

- Rodan, Simona (2019-09-30). Maritime-Related Cults in the Coastal Cities of Philistia during the Roman Period: Legacy and Change. Archaeopress Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-1-78969-257-0.

- Macalister, Robert Alexander Stewart (1980). The Philistines: Their History and Civilization. Library of Alexandria. ISBN 978-1-4655-1749-4.

- Greenfield, Jonas Carl (2001). 'Al Kanfei Yonah. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-12170-6.

- Clermont-Ganneau, Charles (1897). Bibliothèque de l'Ecole des hautes études...: Sciences philologiques et historiques (in French). aE. Bouillon.

- Bochart, Samuel (1712). Samuelis Bocharti Opera omnia. Hoc est Phaleg, Chanaan, et Hierozoicon. Quibus accesserunt Dissertationes variae ad illustrationem sacri codicis aliorumque monumentorum veterum. Praemittitur vita auctoris à Stephano Morino descripta...viri clarissimi Johannes Leusden & Petrus de Villemandy. Editio quarta (in Latin). apud Cornelium Boutesteyn, & Samuelem Luchtmans.

- ^ Aramaic: נשרא (hapax). The reading vulture-god is supported by:

- Bochart, Samuel (1712). Samuelis Bocharti Opera omnia. Hoc est Phaleg, Chanaan, et Hierozoicon. Quibus accesserunt Dissertationes variae ad illustrationem sacri codicis aliorumque monumentorum veterum. Praemittitur vita auctoris à Stephano Morino descripta...viri clarissimi Johannes Leusden & Petrus de Villemandy. Editio quarta (in Latin). apud Cornelium Boutesteyn, & Samuelem Luchtmans.

- The Journal of Philology. Macmillan and Company. 1880.

- Greenfield, Jonas Carl (2001). 'Al Kanfei Yonah. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-12170-6.

- Epstein, Isidore (1935). The Babylonian Talmud ... Soncino Press.

- Neubauer, Adolf (1868). La Géographie du Talmud (in French). Michel Lévy frères. ISBN 978-90-6041-048-6.

- Hastings, James (1908). Encyclopaedia of Religion and Ethics: A-Art. C. Scribner's sons.

- Clermont-Ganneau, Charles (1897). Bibliothèque de l'Ecole des hautes études...: Sciences philologiques et historiques (in French). aE. Bouillon.

- Rodan, Simona (2019-09-30). Maritime-Related Cults in the Coastal Cities of Philistia during the Roman Period: Legacy and Change. Archaeopress Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-1-78969-257-0

- Kasher, Aryeh (1990). Jews and Hellenistic Cities in Eretz-Israel: Relations of the Jews in Eretz-Israel with the Hellenistic Cities During the Second Temple Period (332 BCE - 70 CE). Mohr Siebeck. ISBN 978-3-16-145241-3.

- ^ rhet. Compare Isaiah 46:1

- ^ נשרא, same spelling as Hanan bar Rava. Identified as the vulture-god by Clemont-Ganneau, among others.[19]

References

- ^ a b c Hawting, G. R. (1999). The Idea of Idolatry and the Emergence of Islam: From Polemic to History. Cambridge UP. ISBN 9781139426350.

- ^ Paul Yule, Late Ḥimyarite Vulture Reliefs, in: eds. W. Arnold, M. Jursa, W. Müller, S. Procházka, Philologisches und Historisches zwischen Anatolien und Sokotra, Analecta Semitica In Memorium Alexander Sima (Wiesbaden 2009), 447–455, ISBN 978-3-447-06104-9

- ^ a b c d Greenfield, Jonas Carl (2001). 'Al Kanfei Yonah. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-12170-6.

- ^ Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies. 1975.

- ^ Kaizer, Ted; Hekster, Olivier (2011-05-10). Frontiers in the Roman World: Proceedings of the Ninth Workshop of the International Network Impact of Empire (Durham, 16-19 April 2009). BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-21503-0.

- ^ Dirven, Lucinda. "Horned Deities of Hatra. Meaning and Origin of a Hybrid Phenomenon, in Mesopotamia 50 (2015), 243-260".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ al-Kalbi, Ibn (2015-12-08). Book of Idols. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-7679-2.

- ^ The Bombay Quarterly Magazine and Review. 1853.

- ^ al-Shidyāq, Aḥmad Fāris (2015-10-15). Leg Over Leg: Volumes One and Two. NYU Press. ISBN 978-1-4798-0072-8.

- ^ Tisdall, William St Clair (1911). The Original Sources of the Qur'ân. Society for promoting Christian knowledge.

- ^ Lenormant, François; Chevallier, Elisabeth (1871). Medes and Persians, Phoenicians, and Arabians. J.B. Lippincott.

- ^ Keane, Augustus Henry (1901). The Gold of Ophir, Whence Brought and by Whom?. E. Stanford.

- ^ "Avodah Zarah 11b". www.sefaria.org. Retrieved 2021-03-06.

- ^ "Rashi on Avodah Zarah 11b:8:1". www.sefaria.org. Retrieved 2021-03-06.

- ^ Trimingham, J. Spencer (1990). Christianity Among the Arabs in Pre-Islamic Times. Stacey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-900988-68-1. pg. 20

- ^ B'reishit Rabbah 38:12

- ^ b. Sanhedrin 109a

- ^ "Avodah Zarah 11b:8". www.sefaria.org. Retrieved 2021-03-03.

- ^ Clermont-Ganneau, Charles (1897). "Bibliothèque de l'Ecole des hautes études...: Sciences philologiques et historiques".

- ^ "The Doctrine of Addai (1876). English Translation". www.tertullian.org. Retrieved 2021-03-05.