Spain

Kingdom of Spain | |

|---|---|

| Motto: Plus ultra (Latin) (English: "Further Beyond") | |

| Anthem: Marcha Real (Spanish)[1] (English: "Royal March") | |

Location of Spain (dark green) – in Europe (green & dark grey) | |

| Capital and largest city | Madrid 40°26′N 3°42′W / 40.433°N 3.700°W |

| Official language | Spanish[b][c] |

| Nationality (2024)[3] |

|

| Ethnic groups (2021)[4] |

|

| Religion (2023)[5] |

|

| Demonym(s) |

|

| Government | Unitary parliamentary constitutional monarchy |

• Monarch | Felipe VI |

| Pedro Sánchez | |

| Francina Armengol | |

| Pedro Rollán | |

| Legislature | Cortes Generales |

| Senate | |

| Congress of Deputies | |

| Formation | |

| 20 January 1479 | |

| 14 March 1516 | |

| 9 June 1715 | |

| 19 March 1812 | |

| 29 December 1978 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 505,990[6] km2 (195,360 sq mi) (51st) |

• Water (%) | 0.89[7] |

| Population | |

• 2024 estimate | |

• Density | 96/km2 (248.6/sq mi) (121th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2023) | medium inequality |

| HDI (2022) | very high (27th) |

| Currency | Euro[d] (€) (EUR) |

| Time zone | UTC±0 to +1 (WET and CET) |

• Summer (DST) | UTC+1 to +2 (WEST and CEST) |

| Note: most of Spain observes CET/CEST, except the Canary Islands which observe WET/WEST. | |

| Calling code | +34 |

| ISO 3166 code | ES |

| Internet TLD | .es[e] |

Spain,[f] officially the Kingdom of Spain,[a][g] is a country in Southwestern Europe with territories in North Africa.[12][h] Featuring the southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Europe and the fourth-most populous European Union member state. Spanning across the majority of the Iberian Peninsula, its territory also includes the Canary Islands, in the Eastern Atlantic Ocean, the Balearic Islands, in the Western Mediterranean Sea, and the autonomous cities of Ceuta and Melilla, in Africa. Peninsular Spain is bordered to the north by France, Andorra, and the Bay of Biscay; to the east and south by the Mediterranean Sea and Gibraltar; and to the west by Portugal and the Atlantic Ocean. Spain's capital and largest city is Madrid, and other major urban areas include Barcelona, Valencia, Seville, Zaragoza, Málaga, Murcia and Palma de Mallorca.

In early antiquity, the Iberian Peninsula was inhabited by Celts, Iberians, and other pre-Roman peoples. With the Roman conquest of the Iberian peninsula, the province of Hispania was established. Following the Romanisation and Christianisation of Hispania, the fall of the Western Roman Empire ushered in the inward migration of tribes from Central Europe, including the Visigoths, who formed the Visigothic Kingdom centred on Toledo. In the early eighth century, most of the peninsula was conquered by the Umayyad Caliphate, and during early Islamic rule, Al-Andalus became a dominant peninsular power centred on Córdoba. Several Christian kingdoms emerged in Northern Iberia, chief among them Asturias, León, Castile, Aragon and Navarre; made an intermittent southward military expansion and repopulation, known as the Reconquista, repelling Islamic rule in Iberia, which culminated with the Christian seizure of the Nasrid Kingdom of Granada in 1492. The dynastic union of the Crown of Castile and the Crown of Aragon in 1479 under the Catholic Monarchs is often considered the de facto unification of Spain as a nation state.

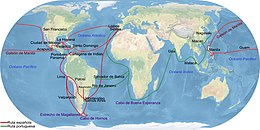

During the Age of Discovery, Spain pioneered the exploration and conquest of the New World, made the first circumnavigation of the globe and formed one of the largest empires in history.[13] The Spanish Empire reached a global scale and spread across all continents, underpinning the rise of a global trading system fueled primarily by precious metals. In the 18th century, the Bourbon Reforms, particularly the Nueva Planta decrees, centralized mainland Spain, strengthening royal authority and modernizing administrative structures.[14] In the 19th century, after the victorious Peninsular War against Napoleonic occupation forces, the following political divisions between liberals and absolutists led to the breakaway of most of the American colonies. These political divisions finally converged in the 20th century with the Spanish Civil War, giving rise to the Francoist dictatorship that lasted until 1975. With the restoration of democracy and its entry into the European Union, the country experienced an economic boom that profoundly transformed it socially and politically. Since the Spanish Golden Age, Spanish art, architecture, music, poetry, painting, literature, and cuisine have been influential worldwide, particularly in Western Europe and the Americas. As a reflection of its large cultural wealth, Spain is the world's second-most visited country, has one of the world's largest numbers of World Heritage Sites, and it is the most popular destination for European students.[15] Its cultural influence extends to over 600 million Hispanophones, making Spanish the world's second-most spoken native language and the world's most widely spoken Romance language.[16]

Spain is a secular parliamentary democracy and a constitutional monarchy,[17] with King Felipe VI as head of state. A developed country, it is a major advanced capitalist economy,[18] with the world's fifteenth-largest by both nominal GDP and PPP-adjusted GDP. Spain is a member of the United Nations, the European Union, the eurozone, North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO), a permanent guest of the G20, and is part of many other international organisations such as the Council of Europe (CoE), the Organisation of Ibero-American States (OEI), the Union for the Mediterranean, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), and the World Trade Organisation (WTO).

Etymology

The name of Spain (España) comes from Hispania, the name used by the Romans for the Iberian Peninsula and its provinces during the Roman Empire. The etymological origin of the term Hispania is uncertain, although the Phoenicians referred to the region as i-shphan-im, possibly meaning "Land of Rabbits" or "Land of Metals".[19] Jesús Luis Cunchillos and José Ángel Zamora, experts in Semitic philology at the Spanish National Research Council (Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, CSIC), conducted a comparative philological study between several Semitic languages and hypothesise that the Phoenician name translates as "land where metals are forged", having determined that the name originated in reference to the gold mines of the Iberian Peninsula.[20] There have been a number of accounts and hypotheses about its origin:

Jesús Luis Cunchillos argues that the root of the term span is the Phoenician word spy, meaning "to forge metals". Therefore, i-spn-ya would mean "the land where metals are forged".[21] It may be a derivation of the Phoenician I-Shpania, meaning "island of rabbits", "land of rabbits" or "edge", a reference to Spain's location at the end of the Mediterranean; Roman coins struck in the region from the reign of Hadrian show a female figure with a rabbit at her feet,[22] and Strabo called it the "land of the rabbits".[23] The word in question actually means "Hyrax", possibly due to the Phoenicians confusing the two animals.[24]

There is also the claim that "Hispania" derives from the Basque word Ezpanna, meaning "edge" or "border", another reference to the fact that the Iberian Peninsula constitutes the southwest corner of the European continent.[25]

History

Prehistory and pre-Roman peoples

Archaeological research at Atapuerca indicates the Iberian Peninsula was populated by hominids 1.3 million years ago.[26]

Modern humans first arrived in Iberia from the north on foot about 35,000 years ago.[27] The best-known artefacts of these prehistoric human settlements are the paintings in the Altamira cave of Cantabria in northern Iberia, which were created from 35,600 to 13,500 BCE by Cro-Magnon.[28][29] Archaeological and genetic evidence suggests that the Iberian Peninsula acted as one of several major refugia from which northern Europe was repopulated following the end of the last ice age.

The two largest groups inhabiting the Iberian Peninsula before the Roman conquest were the Iberians and the Celts. The Iberians inhabited the Mediterranean side of the peninsula. The Celts inhabited much of the interior and Atlantic sides of the peninsula. Basques occupied the western area of the Pyrenees mountain range and adjacent areas; Phoenician-influenced Tartessians flourished in the southwest; and Lusitanians and Vettones occupied areas in the central west. Several cities were founded along the coast by Phoenicians, and trading outposts and colonies were established by Greeks in the East. Eventually, Phoenician-Carthaginians expanded inland towards the meseta; however, due to the bellicose inland tribes, the Carthaginians settled on the coasts of the Iberian Peninsula.

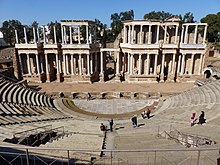

Roman Hispania and the Visigothic Kingdom

During the Second Punic War, roughly between 210 and 205 BCE, the expanding Roman Republic captured Carthaginian trading colonies along the Mediterranean coast. Although it took the Romans nearly two centuries to complete the conquest of the Iberian Peninsula, they retained control of it for over six centuries. Roman rule was bound together by law, language, and the Roman road.[30]

The cultures of the pre-Roman populations were gradually Romanised (Latinised) at different rates depending on what part of the peninsula they lived in, with local leaders being admitted into the Roman aristocratic class.[i][31]

Hispania (the Roman name for the Iberian Peninsula) served as a granary for the Roman market, and its harbours exported gold, wool, olive oil, and wine. Agricultural production increased with the introduction of irrigation projects, some of which remain in use. Emperors Hadrian, Trajan, Theodosius I, and the philosopher Seneca were born in Hispania.[j] Christianity was introduced into Hispania in the 1st century CE, and it became popular in the cities in the 2nd century.[31] Most of Spain's present languages and religions, as well as the basis of its laws, originate from this period.[30] Starting in 170 CE, incursions of North-African Mauri in the province of Baetica took place.[32]

The Germanic Suebi and Vandals, together with the Sarmatian Alans, entered the peninsula after 409, weakening the Western Roman Empire's jurisdiction over Hispania. The Suebi established a kingdom in north-western Iberia, whereas the Vandals established themselves in the south of the peninsula by 420 before crossing over to North Africa in 429. As the western empire disintegrated, the social and economic base became greatly simplified; the successor regimes maintained many of the institutions and laws of the late empire, including Christianity and assimilation into the evolving Roman culture.

The Byzantines established an occidental province, Spania, in the south, with the intention of reviving Roman rule throughout Iberia. Eventually, however, Hispania was reunited under Visigothic rule.

Muslim era and Reconquista

From 711 to 718, as part of the expansion of the Umayyad Caliphate which had conquered North Africa from the Byzantine Empire, nearly all of the Iberian Peninsula was conquered by Muslims from across the Strait of Gibraltar, resulting in the collapse of the Visigothic Kingdom. Only a small area in the mountainous north of the peninsula stood out of the territory seized during the initial invasion. The Kingdom of Asturias-León consolidated upon this territory. Other Christian kingdoms, such as Navarre and Aragon in the mountainous north, eventually surged upon the consolidation of counties of the Carolingian Marca Hispanica.[33] For several centuries, the fluctuating frontier between the Muslim and Christian-controlled areas of the peninsula was along the Ebro and Douro valleys.

Conversion to Islam proceeded at an increasing pace. The muladíes (Muslims of ethnic Iberian origin) are believed to have formed the majority of the population of Al-Andalus by the end of the 10th century.[34][35]

A series of Viking incursions raided the coasts of the Iberian Peninsula in the 9th and 10th centuries.[36] The first recorded Viking raid on Iberia took place in 844; it ended in failure with many Vikings killed by the Galicians' ballistas; and seventy of the Vikings' longships captured on the beach and burned by the troops of King Ramiro I of Asturias.

In the 11th century, the Caliphate of Córdoba collapsed, fracturing into a series of petty kingdoms (Taifas),[37] often subject to the payment of a form of protection money (Parias) to the Northern Christian kingdoms, which otherwise undertook a southward territorial expansion. The capture of the strategic city of Toledo in 1085 marked a significant shift in the balance of power in favour of the Christian kingdoms.[38] The arrival from North Africa of the Islamic ruling sects of the Almoravids and the Almohads achieved temporary unity upon the Muslim-ruled territory, with a stricter, less tolerant application of Islam, and partially reversed some Christian territorial gains.

The Kingdom of León was the strongest Christian kingdom for centuries. In 1188, the first form (restricted to the bishops, the magnates, and 'the elected citizens of each city') of modern parliamentary session in Europe was held in León (Cortes of León).[39] The Kingdom of Castile, formed from Leonese territory, was its successor as strongest kingdom. The kings and the nobility fought for power and influence in this period. The example of the Roman emperors influenced the political objective of the Crown, while the nobles benefited from feudalism.

Muslim strongholds in the Guadalquivir Valley such as Córdoba (1236) and Seville (1248) fell to Castile in the 13th century. The County of Barcelona and the Kingdom of Aragon entered in a dynastic union and gained territory and power in the Mediterranean. In 1229, Majorca was conquered, so was Valencia in 1238. In the 13th and 14th centuries, the North-African Marinids established some enclaves around the Strait of Gibraltar. Upon the conclusion of the Granada War, the Nasrid Sultanate of Granada (the remaining Muslim-ruled polity in the Iberian Peninsula after 1246) capitulated in 1492 to the military strength of the Catholic Monarchs, and it was integrated from then on in the Crown of Castile.[40]

Spanish Empire

In 1469, the crowns of the Christian kingdoms of Castile and Aragon were united by the marriage of their monarchs, Isabella I and Ferdinand II, respectively. In 1492, Jews were forced to choose between conversion to Catholicism or expulsion;[41] as many as 200,000 Jews were expelled from Castile and Aragon. The year 1492 also marked the arrival of Christopher Columbus in the New World, during a voyage funded by Isabella. Columbus's first voyage crossed the Atlantic and reached the Caribbean Islands, beginning the European exploration and conquest of the Americas.

The Treaty of Granada guaranteed religious tolerance towards Muslims,[42] for a few years before Islam was outlawed in 1502 in Castile and 1527 in Aragon, leading the remaining Muslim population to become nominally Christian Moriscos. About four decades after the War of the Alpujarras (1568–1571), over 300,000 moriscos were expelled, settling primarily in North Africa.[43]

The unification of the crowns of Aragon and Castile by the marriage of their sovereigns laid the basis for modern Spain and the Spanish Empire, although each kingdom of Spain remained a separate country socially, politically, legally, and in currency and language.[44][45]

Habsburg Spain was one of the leading world powers throughout the 16th century and most of the 17th century, a position reinforced by trade and wealth from colonial possessions and became the world's leading maritime power. It reached its apogee during the reigns of the first two Spanish Habsburgs—Charles V/I (1516–1556) and Philip II (1556–1598). This period saw the Italian Wars, the Schmalkaldic War, the Dutch Revolt, the War of the Portuguese Succession, clashes with the Ottomans, intervention in the French Wars of Religion and the Anglo-Spanish War.[46]

Through exploration and conquest or royal marriage alliances and inheritance, the Spanish Empire expanded across vast areas in the Americas, the Indo-Pacific, Africa as well as the European continent (including holdings in the Italian Peninsula, the Low Countries and the Franche-Comté). The so-called Age of Discovery featured explorations by sea and by land, the opening-up of new trade routes across oceans, conquests and the beginnings of European colonialism. Precious metals, spices, luxuries, and previously unknown plants brought to the metropole played a leading part in transforming the European understanding of the globe.[47] The cultural efflorescence witnessed during this period is now referred to as the Spanish Golden Age. The expansion of the empire caused immense upheaval in the Americas as the collapse of societies and empires and new diseases from Europe devastated American indigenous populations. The rise of humanism, the Counter-Reformation and new geographical discoveries and conquests raised issues that were addressed by the intellectual movement now known as the School of Salamanca, which developed the first modern theories of what are now known as international law and human rights.

Spain's 16th-century maritime supremacy was demonstrated by the victory over the Ottoman Empire at the Battle of Lepanto in 1571 and over Portugal at the Battle of Ponta Delgada in 1582, and then after the setback of the Spanish Armada in 1588, in a series of victories against England in the Anglo-Spanish War of 1585–1604. However, during the middle decades of the 17th century Spain's maritime power went into a long decline with mounting defeats against the Dutch Republic (Battle of the Downs) and then England in the Anglo-Spanish War of 1654–1660; by the 1660s it was struggling to defend its overseas possessions from pirates and privateers.

The Protestant Reformation increased Spain's involvement in religiously charged wars, forcing ever-expanding military efforts across Europe and in the Mediterranean.[48] By the middle decades of a war- and plague-ridden 17th-century Europe, the Spanish Habsburgs had enmeshed the country in continent-wide religious-political conflicts. These conflicts drained it of resources and undermined the economy generally. Spain managed to hold on to most of the scattered Habsburg empire, and help the imperial forces of the Holy Roman Empire reverse a large part of the advances made by Protestant forces, but it was finally forced to recognise the separation of Portugal and the United Provinces (Dutch Republic), and eventually suffered some serious military reverses to France in the latter stages of the immensely destructive, Europe-wide Thirty Years' War.[49] In the latter half of the 17th century, Spain went into a gradual decline, during which it surrendered several small territories to France and England; however, it maintained and enlarged its vast overseas empire, which remained intact until the beginning of the 19th century.

18th century

The decline culminated in a controversy over succession to the throne which consumed the first years of the 18th century. The War of the Spanish Succession was a wide-ranging international conflict combined with a civil war, and was to cost the kingdom its European possessions and its position as a leading European power.[50]

During this war, a new dynasty originating in France, the Bourbons, was installed. The Crowns of Castile and Aragon had been long united only by the Monarchy and the common institution of the Inquisition's Holy Office.[51] A number of reform policies (the so-called Bourbon Reforms) were pursued by the Monarchy with the overarching goal of centralised authority and administrative uniformity.[52] They included the abolishment of many of the old regional privileges and laws,[53] as well as the customs barrier between the Crowns of Aragon and Castile in 1717, followed by the introduction of new property taxes in the Aragonese kingdoms.[54]

The 18th century saw a gradual recovery and an increase in prosperity through much of the empire. The predominant economic policy was an interventionist one, and the State also pursued policies aiming towards infrastructure development as well as the abolition of internal customs and the reduction of export tariffs.[55] Projects of agricultural colonisation with new settlements took place in the south of mainland Spain.[56] Enlightenment ideas began to gain ground among some of the kingdom's elite and monarchy.

Liberalism and nation state

In 1793, Spain went to war against the revolutionary new French Republic as a member of the first Coalition. The subsequent War of the Pyrenees polarised the country in a reaction against the gallicised elites and following defeat in the field, peace was made with France in 1795 at the Peace of Basel in which Spain lost control over two-thirds of the island of Hispaniola. In 1807, a secret treaty between Napoleon and the unpopular prime minister led to a new declaration of war against Britain and Portugal. French troops entered the country to invade Portugal but instead occupied Spain's major fortresses. The Spanish king abdicated and a puppet kingdom satellite to the French Empire was installed with Joseph Bonaparte as king.

The 2 May 1808 revolt was one of many uprisings across the country against the French occupation.[57] These revolts marked the beginning of a devastating war of independence against the Napoleonic regime.[58] Further military action by Spanish armies, guerrilla warfare and an Anglo-Portuguese allied army, combined with Napoleon's failure on the Russian front, led to the retreat of French imperial armies from the Iberian Peninsula in 1814, and the return of King Ferdinand VII.[59]

During the war, in 1810, a revolutionary body, the Cortes of Cádiz, was assembled to coordinate the effort against the Bonapartist regime and to prepare a constitution.[60] It met as one body, and its members represented the entire Spanish empire.[61] In 1812, a constitution for universal representation under a constitutional monarchy was declared, but after the fall of the Bonapartist regime, the Spanish king dismissed the Cortes Generales, set on ruling as an absolute monarch.

The French occupation of mainland Spain created an opportunity for overseas criollo elites who resented the privilege towards Peninsular elites and demanded retroversion of the sovereignty to the people. Starting in 1809 the American colonies began a series of revolutions and declared independence, leading to the Spanish American wars of independence that put an end to the metropole's grip over the Spanish Main. Attempts to re-assert control proved futile with opposition not only in the colonies but also in the Iberian peninsula and army revolts followed. By the end of 1826, the only American colonies Spain held were Cuba and Puerto Rico. The Napoleonic War left Spain economically ruined, deeply divided and politically unstable. In the 1830s and 1840s, Carlism (a reactionary legitimist movement supportive of an alternative Bourbon branch), fought against the government forces supportive of Queen Isabella II's dynastic rights in the Carlist Wars. Government forces prevailed, but the conflict between progressives and moderates ended in a weak early constitutional period. The 1868 Glorious Revolution was followed by the 1868–1874 progressive Sexenio Democrático (including the short-lived First Spanish Republic), which yielded to a stable monarchic period, the Restoration (1875–1931).[62]

In the late 19th century nationalist movements arose in the Philippines and Cuba. In 1895 and 1896 the Cuban War of Independence and the Philippine Revolution broke out and eventually the United States became involved. The Spanish–American War was fought in the spring of 1898 and resulted in Spain losing the last of its once vast colonial empire outside of North Africa. El Desastre (the Disaster), as the war became known in Spain, gave added impetus to the Generation of '98. Although the period around the turn of the century was one of increasing prosperity, the 20th century brought little social peace. Spain played a minor part in the scramble for Africa. It remained neutral during World War I. The heavy losses suffered by the colonial troops in conflicts in northern Morocco against Riffians forces brought discredit to the government and undermined the monarchy.

Industrialisation, the development of railways and incipient capitalism developed in several areas of the country, particularly in Barcelona, as well as labour movement and socialist and anarchist ideas. The 1870 Barcelona Workers' Congress and the 1888 Barcelona Universal Exposition are good examples of this. In 1879, the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party was founded. A trade union linked to this party, Unión General de Trabajadores, was founded in 1888. In the anarcho-syndicalist trend of the labour movement in Spain, Confederación Nacional del Trabajo was founded in 1910 and Federación Anarquista Ibérica in 1927.

Catalanism and Vasquism, alongside other nationalisms and regionalisms in Spain, arose in that period: the Basque Nationalist Party formed in 1895 and Regionalist League of Catalonia in 1901.

Political corruption and repression weakened the democratic system of the constitutional monarchy of a two-parties system.[63] The July 1909 Tragic Week events and repression exemplified the social instability of the time.

The La Canadiense strike in 1919 led to the first law limiting the working day to eight hours.[64]

After a period of Crown-supported dictatorship from 1923 to 1931, the first elections since 1923, largely understood as a plebiscite on Monarchy, took place: the 12 April 1931 municipal elections. These gave a resounding victory to the Republican-Socialist candidacies in large cities and provincial capitals, with a majority of monarchist councilors in rural areas. The king left the country and the proclamation of the Republic on 14 April ensued, with the formation of a provisional government.

A constitution for the country was passed in October 1931 following the June 1931 Constituent general election, and a series of cabinets presided by Manuel Azaña supported by republican parties and the PSOE followed. In the election held in 1933 the right triumphed and in 1936, the left. During the Second Republic there was a great political and social upheaval, marked by a sharp radicalisation of the left and the right. Instances of political violence during this period included the burning of churches, the 1932 failed coup d'état led by José Sanjurjo, the Revolution of 1934 and numerous attacks against rival political leaders. On the other hand, it is also during the Second Republic when important reforms to modernise the country were initiated: a democratic constitution, agrarian reform, restructuring of the army, political decentralisation and women's right to vote.

Civil War and Francoist dictatorship

The Spanish Civil War broke out in 1936: on 17 and 18 July, part of the military carried out a coup d'état that triumphed in only part of the country. The situation led to a civil war, in which the territory was divided into two zones: one under the authority of the Republican government, that counted on outside support from the Soviet Union and Mexico (and from International Brigades), and the other controlled by the putschists (the Nationalist or rebel faction), most critically supported by Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy. The Republic was not supported by the Western powers due to the British-led policy of non-intervention. General Francisco Franco was sworn in as the supreme leader of the rebels on 1 October 1936. An uneasy relationship between the Republican government and the grassroots anarchists who had initiated a partial social revolution also ensued.

The civil war was viciously fought and there were many atrocities committed by all sides. The war claimed the lives of over 500,000 people and caused the flight of up to a half-million citizens from the country.[65][66] On 1 April 1939, five months before the beginning of World War II, the rebel side led by Franco emerged victorious, imposing a dictatorship over the whole country. Thousands were imprisoned after the civil war in Francoist concentration camps.

The regime remained nominally "neutral" for much of the Second World War, although it was sympathetic to the Axis and provided the Nazi Wehrmacht with Spanish volunteers in the Eastern Front. The only legal party under Franco's dictatorship was the Falange Española Tradicionalista y de las JONS (FET y de las JONS), formed in 1937 upon the merging of the Fascist Falange Española de las JONS and the Carlist traditionalists and to which the rest of right-wing groups supporting the rebels also added. The name of "Movimiento Nacional", sometimes understood as a wider structure than the FET y de las JONS proper, largely imposed over the later's name in official documents along the 1950s.

After the war Spain was politically and economically isolated, and was kept out of the United Nations. This changed in 1955, during the Cold War period, when it became strategically important for the US to establish a military presence on the Iberian Peninsula as a counter to any possible move by the Soviet Union into the Mediterranean basin. US Cold War strategic priorities included the dissemination of American educational ideas to foster modernization and expansion.[67] In the 1960s, Spain registered an unprecedented rate of economic growth which was propelled by industrialisation, a mass internal migration from rural areas to Madrid, Barcelona and the Basque Country and the creation of a mass tourism industry. Franco's rule was also characterised by authoritarianism, promotion of a unitary national identity, National Catholicism, and discriminatory language policies.

Restoration of democracy

In 1962, a group of politicians involved in the opposition to Franco's regime inside the country and in exile met in the congress of the European Movement in Munich, where they made a resolution in favour of democracy.[68][69][70]

With Franco's death in November 1975, Juan Carlos succeeded to the position of King of Spain and head of state in accordance with the Francoist law. With the approval of the new Spanish Constitution of 1978 and the restoration of democracy, the State devolved much authority to the regions and created an internal organisation based on autonomous communities. The Spanish 1977 Amnesty Law let people of Franco's regime continue inside institutions without consequences, even perpetrators of some crimes during transition to democracy like the Massacre of 3 March 1976 in Vitoria or 1977 Massacre of Atocha.

In the Basque Country, moderate Basque nationalism coexisted with a radical nationalist movement led by the armed organisation ETA until the latter's dissolution in May 2018.[71] The group was formed in 1959 during Franco's rule but had continued to wage its violent campaign even after the restoration of democracy and the return of a large measure of regional autonomy.

On 23 February 1981, rebel elements among the security forces seized the Cortes in an attempt to impose a military-backed government. King Juan Carlos took personal command of the military and successfully ordered the coup plotters, via national television, to surrender.[72]

During the 1980s the democratic restoration made possible a growing open society. New cultural movements based on freedom appeared, like La Movida Madrileña. In May 1982 Spain joined NATO, followed by a referendum after a strong social opposition. That year the Spanish Socialist Workers Party (PSOE) came to power, the first left-wing government in 43 years. In 1986 Spain joined the European Economic Community, which later became the European Union. The PSOE was replaced in government by the Partido Popular (PP) in 1996 after scandals around participation of the government of Felipe González in the Dirty war against ETA.

On 1 January 2002, Spain fully adopted the euro, and Spain experienced strong economic growth, well above the EU average during the early 2000s. However, well-publicised concerns issued by many economic commentators at the height of the boom warned that extraordinary property prices and a high foreign trade deficit were likely to lead to a painful economic collapse.[73]

In 2002, the Prestige oil spill occurred with big ecological consequences along Spain's Atlantic coastline. In 2003 José María Aznar supported US president George W. Bush in the Iraq War, and a strong movement against war rose in Spanish society. In March 2004 a local Islamist terrorist group inspired by Al-Qaeda carried out the largest terrorist attack in Western European history when they killed 191 people and wounded more than 1,800 others by bombing commuter trains in Madrid.[74] Though initial suspicions focused on the Basque terrorist group ETA, evidence of Islamist involvement soon emerged. Because of the proximity of the 2004 Spanish general election, the issue of responsibility quickly became a political controversy, with the main competing parties PP and PSOE exchanging accusations over the handling of the incident.[75] The PSOE won the election, led by José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero.[76]

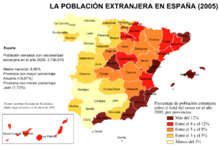

In the early 2000s, the proportion of Spain's foreign born population increased rapidly during its economic boom but then declined due to the financial crisis.[77] In 2005, the Spanish government legalised same sex marriage, becoming the third country worldwide to do so.[78] Decentralisation was supported with much resistance of Constitutional Court and conservative opposition, so did gender politics like quotas or the law against gender violence. Government talks with ETA happened, and the group announced its permanent cease of violence in 2010.[79]

The bursting of the Spanish property bubble in 2008 led to the 2008–16 Spanish financial crisis. High levels of unemployment, cuts in government spending and corruption in Royal family and People's Party served as a backdrop to the 2011–12 Spanish protests.[80] Catalan independentism also rose. In 2011, Mariano Rajoy's conservative People's Party won the election with 44.6% of votes.[81] As prime minister, he implemented austerity measures for EU bailout, the EU Stability and Growth Pact.[82] On 19 June 2014, the monarch, Juan Carlos, abdicated in favour of his son, who became Felipe VI.[83]

In October 2017 a Catalan independence referendum was held and the Catalan parliament voted to unilaterally declare independence from Spain to form a Catalan Republic[84][85] on the day the Spanish Senate was discussing approving direct rule over Catalonia as called for by the Spanish Prime Minister.[86][87] On the same day the Senate granted the power to impose direct rule and Rajoy dissolved the Catalan parliament and called a new election.[88] No country recognised Catalonia as a separate state.[89]

In June 2018, the Congress of Deputies passed a motion of no-confidence against Rajoy and replaced him with the PSOE leader Pedro Sánchez.[90] In 2019, the first ever coalicion government in Spain was formed, between PSOE and Unidas Podemos. Between 2018 and 2024, Spain faced an institutional crisis surrounding the mandate of the General Council of the Judiciary (CGPJ), until finally the mandate got renovated.[91] In January 2020, the COVID-19 virus was confirmed to have spread to Spain, causing life expectancy to drop by more than a year.[92] The European Commission economic recovery package Next Generation EU were created to support the EU member states to recover from the COVID-19 pandemic, and will be in use in the period 2021–2026. In March 2021, Spain became the sixth nation in the world to make active euthanasia legal.[93] Following the general election on 23 July 2023, prime minister Pedro Sánchez once again formed a coalition government, this time with Sumar (successors of Unidas Podemos).[94] In 2024, the first non-independentist Catalan regional president in over a decade, Salvador Illa, was elected, normalising the constitutional and institutional relations between the national and the regional administrations. According to latest polls,[95] only 17.3% of Catalans feel themselves as "only Catalan". 46% of Catalans would answer "as Spanish as Catalan", while 21.8% "more Catalan than Spanish".[96] Accordind to a 2024 poll of University of Barcelona, over 50% of Catalans would vote against independence, while less than 40% would vote in favour.[97]

Geography

At 505,992 km2 (195,365 sq mi), Spain is the world's fifty-first largest country and Europe's fourth largest country. It is some 47,000 km2 (18,000 sq mi) smaller than France. At 3,715 m (12,188 ft), Mount Teide (Tenerife) is the highest mountain peak in Spain and is the third largest volcano in the world from its base. Spain is a transcontinental country, having territory in both Europe and Africa.

Spain lies between latitudes 27° and 44° N, and longitudes 19° W and 5° E.

On the west, Spain is bordered by Portugal; on the south, it is bordered by Gibraltar and Morocco, through its exclaves in North Africa (Ceuta and Melilla, and the peninsula of de Vélez de la Gomera). On the northeast, along the Pyrenees mountain range, it is bordered by France and Andorra. Along the Pyrenees in Girona, a small exclave town called Llívia is surrounded by France.

Extending to 1,214 km (754 mi), the Portugal–Spain border is the longest uninterrupted border within the European Union.[98]

Islands

Spain also includes the Balearic Islands in the Mediterranean Sea, the Canary Islands in the Atlantic Ocean and a number of uninhabited islands on the Mediterranean side of the Strait of Gibraltar, known as plazas de soberanía ("places of sovereignty", or territories under Spanish sovereignty), such as the Chafarinas Islands and Alhucemas. The peninsula of de Vélez de la Gomera is also regarded as a plaza de soberanía. The isle of Alborán, located in the Mediterranean between Spain and North Africa, is also administered by Spain, specifically by the municipality of Almería, Andalusia. The little Pheasant Island in the River Bidasoa is a Spanish-French condominium.

There are 11 major islands in Spain, all of them having their own governing bodies (Cabildos insulares in the Canaries, Consells insulars in Baleares). These islands are specifically mentioned by the Spanish Constitution, when fixing its Senatorial representation (Ibiza and Formentera are grouped, as they together form the Pityusic islands, part of the Balearic archipelago). These islands include Tenerife, Gran Canaria, Lanzarote, Fuerteventura, La Palma, La Gomera and El Hierro in the Canarian archipelago and Mallorca, Ibiza, Menorca and Formentera in the Balearic archipelago.

Mountains and rivers

Mainland Spain is a rather mountainous landmass, dominated by high plateaus and mountain chains. After the Pyrenees, the main mountain ranges are the Cordillera Cantábrica (Cantabrian Range), Sistema Ibérico (Iberian System), Sistema Central (Central System), Montes de Toledo, Sierra Morena and the Sistema Bético (Baetic System) whose highest peak, the 3,478-metre-high (11,411-foot) Mulhacén, located in Sierra Nevada, is the highest elevation in the Iberian Peninsula. The highest point in Spain is the Teide, a 3,718-metre (12,198 ft) active volcano in the Canary Islands. The Meseta Central (often translated as 'Inner Plateau') is a vast plateau in the heart of peninsular Spain split in two by the Sistema Central.

There are several major rivers in Spain such as the Tagus (Tajo), Ebro, Guadiana, Douro (Duero), Guadalquivir, Júcar, Segura, Turia and Minho (Miño). Alluvial plains are found along the coast, the largest of which is that of the Guadalquivir in Andalusia.

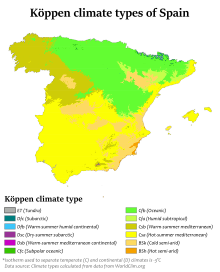

Climate

Three main climatic zones can be separated, according to geographical situation and orographic conditions:[99]

- The Mediterranean climate is characterised by warm/hot and dry summers and is the predominant climate in the country. It has two varieties: Csa and Csb according to the Köppen climate classification.

- The Csa zone is associated with areas with hot summers. It is predominant in the Southern Mediterranean (except southeastern) and Southern Atlantic coast and inland throughout Andalusia, Extremadura and much of the centre of the country. Some areas of Csa, mainly those inland, such as some areas of Castilla-La-Mancha, Extremadura, Madrid and some parts of Andalusia, have cool winters with some continental influences, while the regions with a Mediterranean climate close to the sea have mild winters.

- The Csb zone has warm rather than hot summers, and extends to additional cool-winter areas not typically associated with a Mediterranean climate, such as much of central and northern-central of Spain (e.g. western Castile–León, northeastern Castilla-La Mancha and northern Madrid) and into much rainier areas (notably Galicia).

- The semi-arid climate (BSk, BSh) is predominant in the southeastern quarter of the country, but is also widespread in other areas of Spain. It covers most of the Region of Murcia, southern and central-eastern Valencia, eastern Andalusia, various areas of Castilla-La-Mancha, Madrid and some areas of Extremadura. Further to the north, it is predominant in the upper and mid reaches of the Ebro valley, which crosses southern Navarre, central Aragon and western Catalonia. It is also found in a small area in northern Andalusia and in a small area in central Castilla-León. Precipitation is limited with dry season extending beyond the summer and average temperature depends on altitude and latitude.

- The oceanic climate (Cfb) is located in the northern quarter of the country, especially in the Atlantic region (Basque Country, Cantabria, Asturias, and partly Galicia and Castile–León). It is also found in northern Navarre, in most highlands areas along the Iberian System and in the Pyrenean valleys, where a humid subtropical variant (Cfa) also occurs. Winter and summer temperatures are influenced by the ocean, and have no seasonal drought.

Apart from these main types, other sub-types can be found, like the alpine climate in areas with very high altitude, the humid subtropical climate in areas of northeastern Spain and the continental climates (Dfc, Dfb / Dsc, Dsb) in the Pyrenees as well as parts of the Cantabrian Range, the Central System, Sierra Nevada and the Iberian System, and a typical desert climate (BWk, BWh) in the zone of Almería, Murcia and eastern Canary Islands. Low-lying areas of the Canary Islands average above 18.0 °C (64.4 °F) during their coolest month, thus having influences of tropical climate, although they cannot properly be classified as tropical climates, as according to AEMET, their aridity is high, thus belonging to an arid or semi-arid climate.[100]

Spain is one of the countries that is most affected by the climate change in Europe. In Spain, which already has a hot and dry climate, extreme events such as heatwaves are becoming increasingly frequent.[101][102] The country is also experiencing more episodes of drought and increased severity of these episodes.[103] Water resources will be severely affected in various climate change scenarios.[104] To mitigate the effects of climate change, Spain is promoting an energy transition to renewable energies, such as solar and wind energy.[105]

Fauna and flora

The fauna presents a wide diversity that is due in large part to the geographical position of the Iberian peninsula between the Atlantic and the Mediterranean and between Africa and Eurasia, and the great diversity of habitats and biotopes, the result of a considerable variety of climates and well differentiated regions.

The vegetation of Spain is varied due to several factors including the diversity of the terrain, the climate and latitude. Spain includes different phytogeographic regions, each with its own floral characteristics resulting largely from the interaction of climate, topography, soil type and fire, and biotic factors. The country had a 2019 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 4.23/10, ranking it 130th globally out of 172 countries.[106]

Within the European territory, Spain has the largest number of plant species (7,600 vascular plants) of all European countries.[107]

In Spain there are 17.804 billion trees and an average of 284 million more grow each year.[108]

Politics

The constitutional history of Spain dates back to the constitution of 1812. In June 1976, Spain's new King Juan Carlos dismissed Carlos Arias Navarro and appointed the reformer Adolfo Suárez as Prime Minister.[109][110] The resulting general election in 1977 convened the Constituent Cortes (the Spanish Parliament, in its capacity as a constitutional assembly) for the purpose of drafting and approving the constitution of 1978.[111] After a national referendum on 6 December 1978, 88% of voters approved of the new constitution. As a result, Spain successfully transitioned from a one-party personalist dictatorship to a multiparty parliamentary democracy composed of 17 autonomous communities and two autonomous cities. These regions enjoy varying degrees of autonomy thanks to the Spanish Constitution, which nevertheless explicitly states the indivisible unity of the Spanish nation.

Governance

The Crown

The independence of the Crown, its political neutrality and its wish to embrace and reconcile the different ideological standpoints enable it to contribute to the stability of our political system, facilitating a balance with the other constitutional and territorial bodies, promoting the orderly functioning of the State and providing a channel for cohesion among Spaniards.[112]

The Spanish Constitution provides for a separation of powers between five branches of government, which it refers to as "basic State institutions".[k][113][114] Foremost amongst these institutions is the Crown (La Corona), the symbol of the Spanish state and its permanence.[115] Spain's "parliamentary monarchy" is a constitutional one whereby the reigning king or queen is the living embodiment of the Crown and thus head of state.[l][116][115][117] Unlike in some other constitutional monarchies however, namely the likes of Belgium, Denmark, Luxembourg, The Netherlands, Norway, or indeed the United Kingdom, the monarch is not the fount of national sovereignty or even the nominal chief executive.[118][119][120][121][122][123] Rather, the Crown, as an institution, "...arbitrates and moderates the regular functioning of the institutions..." of the Spanish state.[115] As such, the monarch resolves disputes between the disparate branches, mediates constitutional crises, and prevents abuses of power.[124][125][126][127]

In these respects, the Crown constitutes a fifth moderating branch that does not make public policy or administer public services, functions which rightfully rest with Spain's duly elected legislatures and governments at both the national and regional level. Instead, the Crown personifies the democratic Spanish state, sanctions legitimate authority, ensures the legality of means, and guarantees the execution of the public will.[128][129] Put another way, the monarch fosters national unity at home, represents Spaniards abroad (especially with regard to nations of their historical community), facilitates the orderly operation and continuity of the Spanish government, defends representative democracy, and upholds the rule of law.[114] In other words, the Crown is the guardian of the Spanish constitution and of the rights and freedoms of all Spaniards.[130][m] This stabilising role is in keeping with the monarch's solemn oath upon accession "...to faithfully carry out [my] duties, to obey the Constitution and the laws and ensure that they are obeyed, and to respect the rights of citizens and the Self-governing Communities."[132]

A number of constitutional powers, duties, rights, responsibilities, and functions are assigned to the monarch in his or her capacity as head of state. However, the Crown enjoys inviolability in the performance of these prerogatives and cannot be prosecuted in the very courts which administer justice in its name.[133] For this reason, every official act done by the monarch requires the countersignature of the prime minister or, when appropriate, the president of the Congress of Deputies to have the force of law. The countersigning procedure or refrendo in turn transfers political and legal liability for the royal prerogative to the attesting parties.[134] This provision does not apply to the Royal Household, over which the monarch enjoys absolute control and supervision, or to membership in the Order of the Golden Fleece, which is a dynastic order in the personal gift of the House of Bourbon-Anjou.[135]

The royal prerogatives may be classified by whether they are ministerial functions or reserve powers. Ministerial functions are those royal prerogatives that are, pursuant to the convention established by Juan Carlos I, performed by the monarch after soliciting the advice of the Government, the Congress of Deputies, the Senate, the General Council of the Judiciary, or the Constitutional Tribunal, as the case may be. On the other hand, the reserve powers of the Crown are those royal prerogatives which are exercised in the monarch's personal discretion.[130] Most of the Crown's royal prerogatives are ministerial in practice, meaning the monarch has no discretion in their execution and primarily performs them as a matter of state ceremonial. Nevertheless, when performing said ministerial functions, the monarch has the right to be consulted before acting on advice, the right to encourage a particular course of policy or action, and the right to warn the responsible constitutional authorities against the same. Those ministerial functions are as follows:

- Sanction and promulgate bills duly passed by the Cortes Generales, making them laws. The Spanish Constitution mandates the monarch grant royal assent to each bill within fifteen days of its passage; he or she does not have a right to veto legislation.[136][137]

- Summon the Cortes Generales into session following a general election, dissolve the same upon the expiration of its four-year term, and proclaim the election of the next Cortes. These functions are performed in accordance with the strictures of the Spanish Constitution.[138][139][140][141][142]

- Appoint and dismiss ministers of state on the advice of the prime minister.[143]

- Appoint the president of the Supreme Court on the advice of the General Council of the Judiciary.[144]

- Appoint the president of the Constitutional Tribunal from among its members, on the advice of the full bench, for a term of three years.[145]

- Appoint the Fiscal General, who leads the Prosecution Ministry, on the advice of the Government. Before tendering advice, the Government is required to consult the General Council of the Judiciary.[146]

- Appoint the presidents of the autonomous communities as elected by their respective parliaments.[147]

- Issue decrees approved in the Council of Ministers, confer civil service and military appointments, and award honours and distinctions in the gift of the state. These functions are performed on the advice of the prime minister or another minister designated thereby.[n][148]

- Exercise supreme command and control over the Armed Forces, on the advice of the prime minister.[149]

- Declare war and make peace on the advice of the prime minister and with the prior authorization of the Cortes Generales.[150]

- Ratify treaties, on the advice of the prime minister.[151]

- Accredit Spanish ambassadors and ministers to foreign states and receive the credentials of foreign diplomats to Spain, on the advice of the prime minister.[152]

- Exercise the right of clemency, but without the authority to grant general pardons, on the advice of the prime minister.[153]

- Patronise the Royal Academies.[o][154]

The aforesaid limitations do not apply to the exercise of the Crown's reserve powers, which may be invoked by the monarch when necessary to maintain the continuity and stability of state institutions.[155] For example, the monarch has the right to be kept informed on affairs of state through regular audiences with the Government. For this purpose, the monarch may preside at any time over meetings of the Council of Ministers, but only when requested by the prime minister.[156] Moreover, the monarch may prematurely dissolve the Congress of Deputies, the Senate, or both houses of the Cortes in their entirety before the expiration of their four-year term and, in consequence thereof, concurrently call for snap elections. The monarch exercises this prerogative on the request of the prime minister, after the matter has been discussed by the Council of Ministers. The monarch may choose to accept or refuse the request.[157] The monarch may also order national referendums on the request of the prime minister, but only with the prior authorisation of the Cortes Generales. Again, the monarch may choose to accept or refuse the prime minister's request.[158]

The Crown's reserve powers further extend into constitutional interpretation and the administration of justice. The monarch appoints the 20 members of the General Council of the Judiciary. Of these counselors, twelve are nominated by the supreme, appellate and trial courts, four are nominated by the Congress of Deputies by a majority of three-fifths of its members, and four are nominated by the Senate with the same majority. The monarch may choose to accept or refuse any nomination.[159] In a similar vein, the monarch appoints the twelve magistrates of the Constitutional Tribunal. Of these magistrates, four magistrates are nominated by the Congress of Deputies by a majority of three-fifths of its members, four magistrates are nominated by the Senate with the same majority, two magistrates are nominated by the Government, and two magistrates are nominated by the General Council of the Judiciary. The monarch may choose to accept or refuse any nomination.[160]

However, it is the monarch's reserve powers concerning Government formation that are perhaps the most frequently exercised. The monarch nominates a candidate for prime minister and, as the case may be, appoints or removes him or her from office based on the prime minister's ability to maintain the confidence of the Congress of Deputies.[161] If the Congress of Deputies fails to give its confidence to a new Government within two months, and is thus incapable of governing as a result of parliamentary gridlock, the monarch may dissolve the Cortes Generales and call for fresh elections. The monarch makes use of these reserve powers in his own deliberative judgment after consulting the president of the Congress of Deputies.[162]

Cortes Generales

Legislative authority vests in the Cortes Generales (English: Spanish Parliament, lit. 'General Courts'), a democratically elected bicameral parliament that serves as the supreme representative body of the Spanish people. Aside from the Crown, it is the only basic State institution that enjoys inviolability.[163] It comprises the Congress of Deputies (Congreso de los Diputados), a lower house with 350 deputies, and the Senate (Senado), an upper house with 259 senators.[164][165] Deputies are elected by popular vote on closed lists via proportional representation to serve four-year terms.[166] On the other hand, 208 senators are directly elected by popular vote using a limited voting method, with the remaining 51 senators appointed by the regional legislatures to also serve four-year terms.[167]

Government

Executive authority rests with the Government (Gobierno de España), which is collectively responsible to the Congress of Deputies.[168][169] It consists of the prime minister, one or more deputy prime ministers, and the various ministers of state.[170] These characters together constitute the Council of Ministers which, as Spain's central executive authority, conducts the business of the Government and administers the civil service.[171] The Government remains in office so long as it can maintain the confidence of the Congress of Deputies.

The prime minister, as head of government, enjoys primacy over the other ministers by virtue of his or her ability to advise the monarch as to their appointment and dismissal.[172] Moreover, the prime minister has plenary authority conferred by the Spanish Constitution to direct and coordinate the Government's policies and administrative actions.[173] The Spanish monarch nominates the prime minister after consulting representatives from the different parliamentary groups and in turn formally appoints him or her to office upon a vote of investiture in the Congress of Deputies.[174]

Administrative divisions

Autonomous communities

Spain's autonomous communities are the first level administrative divisions of the country. They were created after the current constitution came into effect (in 1978) in recognition of the right to self-government of the "nationalities and regions of Spain".[175] The autonomous communities were to comprise adjacent provinces with common historical, cultural, and economic traits. This territorial organisation, based on devolution, is known in Spain as the "State of Autonomies" (Estado de las Autonomías). The basic institutional law of each autonomous community is the Statute of Autonomy. The Statutes of Autonomy establish the name of the community according to its historical and contemporary identity, the limits of its territories, the name and organisation of the institutions of government and the rights they enjoy according to the constitution.[176] This ongoing process of devolution means that, while officially a unitary state, Spain is nevertheless one of the most decentralised countries in Europe, along with federations like Belgium, Germany, and Switzerland.[177]

Catalonia, Galicia and the Basque Country, which identified themselves as nationalities, were granted self-government through a rapid process. Andalusia also identified itself as a nationality in its first Statute of Autonomy, even though it followed the longer process stipulated in the constitution for the rest of the country. Progressively, other communities in revisions to their Statutes of Autonomy have also taken that denomination in accordance with their historical and modern identities, such as the Valencian Community,[178] the Canary Islands,[179] the Balearic Islands,[180] and Aragon.[181]

The autonomous communities have wide legislative and executive autonomy, with their own elected parliaments and governments as well as their own dedicated public administrations. The distribution of powers may be different for every community, as laid out in their Statutes of Autonomy, since devolution was intended to be asymmetrical. For instance, only two communities—the Basque Country and Navarre—have full fiscal autonomy based on ancient foral provisions. Nevertheless, each autonomous community is responsible for healthcare and education, among other public services.[182] Beyond these competencies, the nationalities—Andalusia, the Basque Country, Catalonia, and Galicia—were also devolved more powers than the rest of the communities, among them the ability of the regional president to dissolve the parliament and call for elections at any time. In addition, the Basque Country, the Canary Islands, Catalonia, and Navarre each have autonomous police corps of their own: Ertzaintza, Policía Canaria, Mossos d'Esquadra, and Policía Foral respectively. Other communities have more limited forces or none at all, like the Policía Autónoma Andaluza in Andalusia or BESCAM in Madrid.[183]

Provinces and municipalities

Autonomous communities are divided into provinces, which served as their territorial building blocks. In turn, provinces are divided into municipalities. The existence of both the provinces and the municipalities is guaranteed and protected by the constitution, not necessarily by the Statutes of Autonomy themselves. Municipalities are granted autonomy to manage their internal affairs, and provinces are the territorial divisions designed to carry out the activities of the State.[184]

The current provincial division structure is based—with minor changes—on the 1833 territorial division by Javier de Burgos, and in all, the Spanish territory is divided into 50 provinces. The communities of Asturias, Cantabria, La Rioja, the Balearic Islands, Madrid, Murcia and Navarre are the only communities that comprise a single province, which is coextensive with the community itself. In these cases, the administrative institutions of the province are replaced by the governmental institutions of the community.

Foreign relations

After the return of democracy following the death of Franco in 1975, Spain's foreign policy priorities were to break out of the diplomatic isolation of the Franco years and expand diplomatic relations, enter the European Community, and define security relations with the West.

As a member of NATO since 1982, Spain has established itself as a participant in multilateral international security activities. Spain's EU membership represents an important part of its foreign policy. Even on many international issues beyond western Europe, Spain prefers to coordinate its efforts with its EU partners through the European political co-operation mechanisms.[vague]

Spain has maintained its special relations with Hispanic America and the Philippines. Its policy emphasises the concept of an Ibero-American community, essentially the renewal of the concept of "Hispanidad" or "Hispanismo", as it is often referred to in English, which has sought to link the Iberian Peninsula with Hispanic America through language, commerce, history and culture. It is fundamentally "based on shared values and the recovery of democracy."[185]

The country is involved in a number of territorial disputes. Spain claims Gibraltar, an Overseas Territory of the United Kingdom, in the southernmost part of the Iberian Peninsula.[186][187][188] Another dispute surrounds the Savage Islands; Spain claims that they are rocks rather than islands, and therefore does not accept the Portuguese Exclusive Economic Zone (200 nautical miles) generated by the islands.[189][190] Spain claims sovereignty over the Perejil Island, a small, uninhabited rocky islet located in the South shore of the Strait of Gibraltar; it was the subject of an armed incident between Spain and Morocco in 2002. Morocco claims the Spanish cities of Ceuta and Melilla and the plazas de soberanía islets off the northern coast of Africa. Portugal does not recognise Spain's sovereignty over the territory of Olivenza.[191]

Military

The Spanish Armed Forces are divided into three branches: Army (Ejército de Tierra); Navy (Armada); and Air and Space Force (Ejército del Aire y del Espacio).[192]

The armed forces of Spain are known as the Spanish Armed Forces (Fuerzas Armadas Españolas). Their commander-in-chief is the King of Spain, Felipe VI.[193] The next military authorities in line are the Prime Minister and the Minister of Defence. The fourth military authority of the State is the Chief of the Defence Staff (JEMAD).[194] The Defence Staff (Estado Mayor de la Defensa) assists the JEMAD as auxiliary body.

The Spanish armed forces are a professional force with a strength in 2017 of 121,900 active personnel and 4,770 reserve personnel. The country also has the 77,000 strong Civil Guard which comes under the control of the Ministry of defense in times of a national emergency. The Spanish defense budget is 5.71 billion euros (US$7.2 billion) a 1% increase for 2015. The increase comes because of security concerns in the country.[195] Military conscription was suppressed in 2001.[196]

According to the 2024 Global Peace Index, Spain is the 23rd most peaceful country in the world.[197]

Human rights

The Spanish Constitution of 1978 "protect all Spaniards and all the peoples of Spain in the exercise of human rights, their cultures and traditions, languages and institutions".[198]

According to Amnesty International (AI), government investigations of alleged police abuses are often lengthy and punishments were light.[199] Violence against women was a problem, which the Government took steps to address.[200][201]

Spain provides one of the highest degrees of liberty in the world for its LGBT community. Among the countries studied by Pew Research in 2013, Spain is rated first in acceptance of homosexuality, with 88% of those surveyed saying that homosexuality should be accepted.[202]

The Cortes Generales approved the Gender Equality Act in 2007 aimed at furthering equality between genders in Spanish political and economic life.[203] According to Inter-Parliamentary Union data as of 1 September 2018, 137 of the 350 members of the Congress were women (39.1%), while in the Senate, there were 101 women out of 266 (39.9%), placing Spain 16th on their list of countries ranked by proportion of women in the lower (or single) House.[204] The Gender Empowerment Measure of Spain in the United Nations Human Development Report is 0.794, 12th in the world.[205]

Economy

Spain has a mixed economy that combines elements of free-market capitalism with social welfare and state intervention. It is one of 19 countries with a nominal gross domestic product (GDP) exceeding $1 trillion per year, ranking 15th largest worldwide and fourth largest both in the European Union and within the eurozone. Spain is classified as a high-income economy by the World Bank and an advanced economy by the International Monetary Fund. As of 2024, it is the fastest growing major advanced economy in the world,[206] growing nearly four times higher than the eurozone average.[207]

Spain began industrializing in the late 18th century, albeit more gradually and unevenly than other European countries; industry was limited mostly to Catalonia (primarily textile manufacturing) and the Basque Country (iron and steel production).[208] Overall economic growth was slower than in most major western European countries, and Spain remained relatively underdeveloped by the early 20th century.[208] The Spanish Civil War, followed by failed autarkic and interventionist policies that were worsened by international isolation, left the economy on the brink of collapse by the late 1950s. Technocratic reforms were enacted to avert the crisis, laying the groundwork for the Spanish economic miracle, a period of rapid growth from 1960 until 1974, during which Spain’s economy grew an average of 6.6 percent per year, exceeding every country except Japan.[208]

Since its transition to democracy in the late 1970s, Spain has generally sought to liberalise its economy and deepen regional and international integration. It joined the European Economic Community—now the European Union—in 1986 and implemented policies and reforms that allowed for its participation in the inaugural launch of the euro in 1999. Spain's largest trade and investment partners are within the EU and eurozone, including its four largest export markets; EU membership also coincided with a tripling of foreign direct investment from 1990 to 2000. Spain was among the countries hit hardest by the 2007–2008 global financial crisis and subsequent euro-zone debt crisis, enduring a protracted recession that persisted through 2014.

Spain has long struggled with high unemployment, which has never fallen below 8 percent since the 1980s; it stood at 11.21 percent in October 2024.[209] Youth unemployment is particularly severe by both global and regional standards; at 25.8 percent (as of June 2024), it is the highest among EU members and well above the EU average of 14.6 percent.[210][211] Perennial weak points of Spain's economy include a large informal economy;[212][213][214] an education system that performs poorly compared to most developed countries;[215] and low rates of private sector investment.[216]

Since the 1990s, which saw a wave of privatisations,[217] several Spanish companies have reached multinational status; they maintain a strong and leading presence in Latin America—where Spain is the second largest foreign investor after the United States—but have also expanded into Asia, especially China and India.[218] As of 2023, Spain was home to eight of the 500 largest companies in the world by annual revenue, according to the Fortune Global 500; these include Banco Santander, the 19th-largest banking institution in the world; electric utility Iberdrola, the world's largest renewable energy operator;[219] and Telefónica, one of the largest telephone operators and mobile network providers. Twenty Spanish companies are listed in the 2023 Forbes Global 2000 ranking of the 2,000 largest public companies, reflecting diverse sectors such as construction (ACS Group), aviation (ENAIRE), pharmaceuticals (Grifols), and transportation (Ferrovial).[220] Additionally, one of Spain's largest private sector entities is Mondragon Corporation, the world's largest worker-owned cooperative.

The automotive industry is one of the largest employers in the country and a major contributor to economic growth, accounting for one-tenth of gross domestic product and 18 percent of total exports (including vehicles and auto-parts). In 2023, Spain produced 2.45 million automobiles—of which over 2.1 million were exported abroad—ranking eighth in the world and second in Europe (after Germany) by total number;[221] it is estimated that Spain will maintain this position by the end of 2024.[222] In total, 89 percent of vehicles and 60% of auto-parts manufactured in Spain were exported worldwide in 2023; the total external trade surplus of vehicles alone reached €18.8bn in 2023. Overall, the automotive industry supports nearly 2 million jobs, or 9 percent of the labor force.[221]

Tourism

In 2023, Spain was the second most visited country in the world only behind France, recording 85 million tourists. The headquarters of the World Tourism Organisation are located in Madrid.

Spain's geographic location, popular coastlines, diverse landscapes, historical legacy, vibrant culture, and excellent infrastructure have made the country's international tourist industry among the largest in the world. In the last five decades, international tourism in Spain has grown to become the second largest in the world in terms of spending, worth approximately 40 billion Euros or about 5% of GDP in 2006.[223][224]

Castile and Leon is the Spanish leader in rural tourism linked to its environmental and architectural heritage.

Energy

In 2010 Spain became the solar power world leader when it overtook the United States with a massive power station plant called La Florida, near Alvarado, Badajoz.[225][226] Spain is also Europe's main producer of wind energy.[227][228] In 2010 its wind turbines generated 16.4% of all electrical energy produced in Spain.[229][230][231] On 9 November 2010, wind energy reached a historic peak covering 53% of mainland electricity demand[232] and generating an amount of energy that is equivalent to that of 14 nuclear reactors.[233] Other renewable energies used in Spain are hydroelectric, biomass and marine.[234]

Non-renewable energy sources used in Spain are nuclear (8 operative reactors), gas, coal, and oil. Fossil fuels together generated 58% of Spain's electricity in 2009, just below the OECD mean of 61%. Nuclear power generated another 19%, and wind and hydro about 12% each.[235]

Science and technology

The Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (CSIC) is the leading public agency dedicated to scientific research in the country. It ranked as the 5th top governmental scientific institution worldwide (and 32nd overall) in the 2018 SCImago Institutions Rankings.[236] Spain was ranked 28th in the Global Innovation Index in 2024.[237]

Higher education institutions perform about a 60% of the basic research in the country.[238] Likewise, the contribution of the private sector to R&D expenditures is much lower than in other EU and OECD countries.[239]

Transport

The Spanish road system is mainly centralised, with six highways connecting Madrid to the Basque Country, Catalonia, Valencia, West Andalusia, Extremadura and Galicia. Additionally, there are highways along the Atlantic (Ferrol to Vigo), Cantabrian (Oviedo to San Sebastián) and Mediterranean (Girona to Cádiz) coasts. Spain aims to put one million electric cars on the road by 2014 as part of the government's plan to save energy and boost energy efficiency.[240] The former Minister of Industry Miguel Sebastián said that "the electric vehicle is the future and the engine of an industrial revolution."[241]

As of July 2024, the Spanish high-speed rail network is the longest HSR network in Europe with 3,966 km (2,464 mi)[242] and the second longest in the world, after China's. It is linking Málaga, Seville, Madrid, Barcelona, Valencia and Valladolid, with the trains operated at commercial speeds up to 330 km/h (210 mph).[243] On average, the Spanish high-speed train is the fastest one in the world, followed by the Japanese bullet train and the French TGV.[244] Regarding punctuality, it is second in the world (98.5% on-time arrival) after the Japanese Shinkansen (99%).[245]

There are 47 public airports in Spain. The busiest one is the airport of Madrid (Barajas), with 60 million passengers in 2023, being the world's 15th busiest airport, as well as the European Union's third busiest. The airport of Barcelona (El Prat) is also important, with 50 million passengers in 2023, being the world's 30th-busiest airport. Other main airports are located in Majorca, Málaga, Las Palmas (Gran Canaria), and Alicante.

- High-speed AVE Class 103 train near Vinaixa, Madrid-Barcelona line. Spain has the longest high-speed rail network in Europe.[242]

- The Port of Valencia, one of the busiest in the Golden Banana

Demographics

In 2024, Spain had a population of 48,946,035 people as recorded by Spain's Instituto Nacional de Estadística.[246] Spain's population density, at 96/km2 (249.2/sq mi), is lower than that of most Western European countries and its distribution across the country is very unequal. With the exception of the region surrounding the capital, Madrid, the most populated areas lie around the coast. The population of Spain has risen 2+1⁄2 times since 1900, when it stood at 18.6 million, principally due to the spectacular demographic boom in the 1960s and early 1970s.[247]

In 2022, the average total fertility rate (TFR) across Spain was 1.16 children born per woman,[248] one of the lowest in the world, below the replacement rate of 2.1, it remains considerably below the high of 5.11 children born per woman in 1865.[249] Spain subsequently has one of the oldest populations in the world, with the average age of 43.1 years.[250]

Native Spaniards make up 86.5% of the total population of Spain. After the birth rate plunged in the 1980s and Spain's population growth rate dropped, the population again trended upward initially upon the return of many Spaniards who had emigrated to other European countries during the 1970s, and more recently, fuelled by large numbers of immigrants who make up 12% of the population. The immigrants originate mainly in Latin America (39%), North Africa (16%), Eastern Europe (15%), and Sub-Saharan Africa (4%).[251]

In 2008, Spain granted citizenship to 84,170 persons, mostly to people from Ecuador, Colombia and Morocco.[252] Spain has a number of descendants of populations from former colonies, especially Latin America and North Africa. Smaller numbers of immigrants from several Sub-Saharan countries have recently been settling in Spain. There are also sizeable numbers of Asian immigrants, most of whom are of Middle Eastern, South Asian and Chinese origin. The single largest group of immigrants are European; represented by large numbers of Romanians, Britons, Germans, French and others.[253]

Urbanisation

| Rank | Name | Autonomous community | Pop. | Rank | Name | Autonomous community | Pop. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Madrid  Barcelona |

1 | Madrid | Community of Madrid | 3,332,035 | 11 | Bilbao | Basque Country | 346,096 |  Valencia  Seville |

| 2 | Barcelona | Catalonia | 1,660,122 | 12 | Córdoba | Andalusia | 323,763 | ||

| 3 | Valencia | Valencian Community | 807,693 | 13 | Valladolid | Castile and León | 297,459 | ||

| 4 | Seville | Andalusia | 684,025 | 14 | Vigo | Galicia | 293,652 | ||

| 5 | Zaragoza | Aragon | 682,513 | 15 | L'Hospitalet | Catalonia | 274,455 | ||

| 6 | Málaga | Andalusia | 586,384 | 16 | Gijón | Principality of Asturias | 258,313 | ||

| 7 | Murcia | Region of Murcia | 469,177 | 17 | Vitoria-Gasteiz | Basque Country | 255,886 | ||

| 8 | Palma | Balearic Islands | 423,350 | 18 | A Coruña | Galicia | 247,376 | ||

| 9 | Las Palmas | Canary Islands | 378,027 | 19 | Elche | Valencian Community | 238,293 | ||

| 10 | Alicante | Valencian Community | 349,282 | 20 | Granada | Andalusia | 230,595 | ||

Immigration

According to the official Spanish statistics (INE) there were 6.6 million foreign residents in Spain in 2024 (13.5%)[254] while all citizens born outside of Spain were 8.9 million in 2024, 18.31% of the total population.[255]

According to residence permit data for 2011, more than 860,000 were Romanian, about 770,000 were Moroccan, approximately 390,000 were British, and 360,000 were Ecuadorian.[256] Other sizeable foreign communities are Colombian, Bolivian, German, Italian, Bulgarian, and Chinese. There are more than 200,000 migrants from Sub-Saharan Africa living in Spain, principally Senegaleses and Nigerians.[257] Since 2000, Spain has experienced high population growth as a result of immigration flows, despite a birth rate that is only half the replacement level. This sudden and ongoing inflow of immigrants, particularly those arriving illegally by sea, has caused noticeable social tension.[258]