Moonshaft

Moonshaft or Mooncave is the name given to a large mysterious object allegedly located somewhere in an unspecified mountain range in Slovakia. Moonshaft was allegedly discovered in 1944 during the Slovak National Uprising by military commander Antonín Horák who later emigrated from Czechoslovakia to the United States via France and changed his name to Tony Horak. In 1965, Horak published an excerpt from his diary in the National Speleological Society News. In 1972, French author Jacques Bergier included Moonshaft in his book Le Livre de l'inexplicable calling it one of the biggest mysteries ever. Due to the political situation in Czechoslovakia after 1968, the first attempts to find Moonshaft took place as late as in 1980. Some of the theories on the origin of the Moonshaft include geological anomaly, ancient copper mine, entrance to an underground city, extraterrestrial spaceship, etc. The story remains very popular among speleologists, paranormal investigators, and various adventurers who regularly try to explore auspicious locations in Slovakia as well as learn more about Horak and the events from his diary.[1][2]

Diary

According to Horak's diary, in autumn of 1944, he served as a commander of a military unit that operated somewhere in the Tatra mountains. Horak's unit got ambushed by Wehrmacht while hiding in a trench. Horak was shot and stabbed in his hand, and lost consciousness after being hit in the head with a rifle stock. He woke up on 22 October still lying in the trench. He was treated by a local herdsman Slávek, who managed to find two more wounded soldiers Jurek and Martin. Martin was immobile so they constructed a stretcher and set on a four-hour trip to a shelter in a mysterious cave. Slávek told Horak that it was only his second visit to the cave and that they should not attempt to explore its deeper sections because the cave was full of deep pits with dangerous gasses and that the place was most likely haunted. Slávek wrote some symbols on the wall next to a crack at the back of the cave, read a couple of lines from his Bible, and then told the soldiers that he would be back in the afternoon with some food and medicine. He returned with his daughter Hana and provided the men with bandages and aspirin telling them he would bring some food the next day. But due to worsened weather, Horak realized Slávek won't be able to return any time soon and the men would be starving.

The next day, 23 October, the only "meal" the three had was hot water with a few drops of slivovitz. Horak decided to break his promise not to venture deeper into the cave. He hoped to find some hibernating animals. Equipped with torches from pinewood, field pickax, and his rifle, he crawled through the crack and learned that navigating in the rear passages of the cave was quite easy. He continued deeper into the cave for approximately 90 minutes until he reached a small vent. When he crawled through, he was astonished to find himself in a large hall with a big grotto decorated with multiple white stalactites and stalagmites covered with enamel-like material. In the grotto, he saw a large dark cylindrical object that was completely smooth. There was a big diagonal crack in the object. Horak, unsure what was inside, threw in some drip-stone fragments and although he could hear water murmuring, the stone made a click sound that indicated the object was hollow and had a solid floor. Horak then tried to use his pickax to disrupt the black material, but he failed to leave even a scratch. He then returned to his comrades without telling them about his discovery. He used their belts to create a rope, explaining that he needed it to catch some bats. He returned to the cave the next day and used the rope to climb to the black shaft. He learned it had a shape of a crescent moon with approx. 25 m (82 ft) in diameter. Horak discovered the floor was steep and covered in clay and limestone. He then unsuccessfully tried to illuminate the ceiling of the shaft. He also noticed that every sound he made inside of the shaft was extremely amplified. After a brief examination of the shaft, Horak climbed out with no difficulties and returned to their shelter.

He visited the shaft again the next day taking his dismantled pickax inside. He tried digging in both of its corners. In one of them, he found a skeletal remains of some animal later identified in Uzhhorod as a cave bear. This species had gone extinct some 25 thousand years ago. This indicated that the shaft had used to be opened at some point and the bear had fallen in. It also proved the shaft to be considerably old. He further found a set of horizontal grooves that seemed to be hotter than the rest of the shaft. In the evening, Slávek and his second daughter Olga brought some meat. Horak did not tell them anything about his discovery. The following day, he explored the other corner of the Moonshaft but found no ridges or anything of importance. He then fired two shots upwards in an attempt to disrupt the wall, but this only produced some green sparkles, smoke and terrible noise. On his way out he tried to collect the unknown enamel-like material from the grotto but it was too fragile to be transported so he decided to create a sticky substance by boiling some bat claws and use it the next time he visits the place. On 26 October, Horak tried to look around for another entrance to the cave, but could not find any. During the night, Martin passed away and the two remaining men could finally leave. Horak returned to the Moonshaft for the last time. He lowered in a bottle with a piece of belt with some basic data written on it and the back of his pocket watch. He then concealed the narrow passage leading to the cave hall with stones.

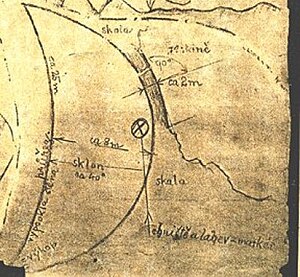

On 27 October Horak and Jurek met Slávek for the last time. Jurek, already able to walk longer distances, proposed to Hana and she accepted. Horak also wrote Martin's death certificate and paid Slávek to raise a wooden cross in his memory when possible. They then carried Martin's body to the original trench where he had suffered the fatal wound. Both men then continued walking to Košice. They later met a partisan group and decided to join them. At the end of the diary, Horak recalls his last visit to the place at the end of the war when he tried to find an alternative entrance to the shaft and also planned to visit Slávek. He learned that Jurek and Hana had moved to Bratislava and Slávek lived in a village called Ždiar. Horak expresses his wish that the Moonshaft is carefully studied by scientists and never becomes a tourist attraction.[3] The diary also contains specific coordinates (49.2 N and 20.7 E) that were most likely added by the publisher to help American readers locate the Tatra mountains.[2]

Further investigation

The diary mentions villages Zdar, Lubocna and Plavnica; the first two do not exist in Slovakia, but the names are reminiscent of the actual villages Ždiar, Ľubochňa and Plavnica. The main problem preventing any serious research was the political situation in former Czechoslovakia that was out of limits for explorers from the United States who were the only ones to discuss the subject directly with Horak. Ted Phillips and Dr. J. Allen Hynek (Project Blue Book) visited Horak in his home in Pueblo, Colorado in 1970. Horak showed them photos he took during his last trip to the site and provided them with some additional information about the location of the cave. Ted Phillips started project "Tatra" which was expected to result in an expedition to Czechoslovakia, but the plans were halted due to safety concerns. In 1975, one year before his death, Horak met researcher Andre Estival and allegedly gave him important materials, but this has never been confirmed. The first field research was carried out by Czech explorers Ivan Mackerle and Michal Brumlík in 1980. In 1982 an official research was performed by the local Museum of Slovak Karst. Both groups failed to find any reliable information about herder Slávek and his daughters. The details of the military operations that Horak described in his diary also seemed rather inaccurate. The first snow in Tatras in 1944 fell in November although Horak mentions avalanches and snowdrifts already in October. Mackerle believed that all these inaccuracies were included by purpose to mislead people looking for sensations. Before his death, Ivan Mackerle passed his materials to other researchers.[4][1]

The first popular scientific article about the Moonshaft was published in 1990 by Czech geologist Václav Cílek. In 1994 another Czech geologist Walter Pavliš visited several unexplored caves in the Tatra mountains. In one of them he found letters H.A. (Horák Antonín), number 23 (23 October) and 6 crossed lines (6 days in cave) carved into the stone. But this cave had no opening in the rear wall. Walter Pavliš was also able to find many information about the life and family of Tony Horak.[4] In 1999 Ted Phillips finally visited Slovakia and explored some of the caves Horak told him about in 1970. Phillips later admitted he was not able to reach the Moonshaft due to a partial collapse of the cave. In his presentation during a MUFON conference in 2015, Phillips showed images of various places in Belianske Tatry and High Tatras claiming to be taken from around the cave's entrance.[2]

Slovak authors Robert K. Lesniakiewicz and Miloš Jesenský (pseudonym Manfred Jensen) published their own discoveries in Poland (in Tajemnica Księżycowej Jaskini (2006) and Powrót do Księżycowej Jaskini (2010)) and later in the United States (The Mooncave Mystery (2020)). They believe the Moonshaft to be a section of an underground network of tunnels related to the mysterious glass tunnels in Babia Góra in Poland. Czech author Martin Lavay performed his own excessive research and discovered that fights similar to those described in Horak's diary occurred in Low Tatras close to villages Telgárt and Vernár. Together with author Jaroslav Mareš and researcher Erik Vojtek, they found an extraordinary rock formation they called "rock eye" near mountain Kráľova hoľa. However, due to the national park rules, they were not allowed to go any near the object. Lavay published the results of his research in his book Měsíční jeskyně (2019) and on Youtube channel záhady.info. Jaroslav Mareš shot a segment for his project badatele.net. In 2019 Slovak web portal Cez Okno received an information, that one of their followers identified a place in a small mountain range Baruchňa where vegetation grew in a shape of a crest. He believed the Mooshaft to be a slickenside – two enormous blocks of sandstone moved in opposite directions which resulted in smoothing and darkening of their surfaces. Natural geological processes caused the gap between the two blocks to grow bigger which created the unusual cavity. However, no proof that the place in Baruchňa is a Moonshaft was presented.[5] The same year, explorer Erik Batysta visited a cave in Belianské Tatry. He found a fireplace, letters written on one of its walls and a pile of stones that looked like a grave. The cave had an opening in the rear wall but seemed to be too unstable to be explored safely. Part of the cave collapsed later that year.[2]

References

- ^ a b "Slovenská republika :: Ivan Mackerle". www.mackerle.cz. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- ^ a b c d Lavay, Martin (2019). Měsíční šachta. XYZ.

- ^ T. Horak, Antonin (March 1965). "The Moonshaft". National Speleological Society News. 23: 30–34.

- ^ a b "Za tajemstvím Měsíční šachty". www.novakoviny.eu. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- ^ "MESAČNÁ ŠACHTA KONEČNE LOKALIZOVANÁ? II. (Geologická štúdia) | CEZ OKNO". www.cez-okno.net. Retrieved 25 May 2020.