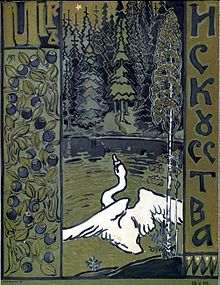

Mir iskusstva

Mir iskusstva (Russian: «Мир искусства», IPA: [ˈmʲir ɪˈskustvə], World of Art) was both a Russian magazine and the artistic movement it fostered, playing a significant role in shaping the Russian avant-garde. the movement was deeply influential to Russian artists who contributed to the 20th century revolution in European art. The magazine itself had limited circulation outside of Russia, as it remained a central part of the development of the Russian modernism movement. .[1]

Foundation of Mir Iskustva

The artistic group known as the Miriskusniki was founded in November 1898 by a collective of students that included Alexandre Benois, Konstantin Somov, Dmitry Filosofov, Léon Bakst, and Eugene Lansere.[2][3]the group emerged from a shared vision to challenge the conventional artistic norms of the time and introduce a fresh, individualistic approach to Russian art. the genesis of Mir Iskustva can be traced back to organization of the Exhibition of Russian and Finnish Artists in the Stieglitz Museum of Applied Arts in Saint Petersburg.[4]

In 1899, the group laughed the magazine, Mir Iskustva, which played a pivotal role in their mission to reshape the Russian artistic landscape. The journal was cofounded in Saint Petersburg by Alexandre Benois, Léon Bakst, and Sergei Diaghilev (the Chief Editor).[4] the group sought to break away from the rigid, academic traditions upheld by the Peredvizhniki (wanderers).[5]They advocated for artistic freedom, individual expression, and celebrated Art Nouveau aesthetic and other principles of Art Nouveau. The theoretical foundation of the group’s artistic ideology was articulated through a series of seminal articles by Diaghilev, which were published in the journal's early issues (Nos. 1/2 and 3/4). These writings included titles such as "Difficult Questions," "Our Imaginary Degradation," "Permanent Struggle," "In Search of Beauty," and "The Fundamentals of Artistic Appreciation." Through these pieces, Diaghilev outlined the group’s critical stance on contemporary art and their vision for the future of Russian culture, which was centered on a commitment to beauty, individualism, and innovation.

Classical period

The Mir Iskustva group entered its "classical period" from 1898 to 1904, during which it organized a series of six significant exhibitions that showcased its avant-garde ideas and artistic endeavors. These exhibitions played a key role in challenging the status quo of Russian art at the time, establishing the group as a force of innovation and cultural change. The exhibitions were as follows:

its "classical period" (1898-1904) the art group organized six exhibitions: 1899 (International), 1900, 1901 (At the Imperial Academy of Arts, Saint Petersburg), 1902 (Moscow and Saint Petersburg), 1903, 1906 (Saint Petersburg). The sixth exhibition was seen as a Diaghilev's attempt to prevent the separation from the Moscow members of the group who organized a separate "Exhibition of 36 artists" (1901) and later "The Union of Russian Artists" group (from 1903).[6] The magazine ended in 1904.[6] – The first exhibition was international in scope, featuring works from both Russian and foreign artists.

- 1899 – The first exhibition was international in scope, featuring works from both Russian and foreign artists.

- 1900– This exhibition continued the group's commitment to expanding the reach of their artistic ideals.

- 1901– Held at the prestigious Imperial Academy of Arts in Saint Petersburg, this exhibition marked a high point for the group, drawing attention from the artistic and intellectual elite.

- 1902 – The group presented exhibitions in both Moscow and Saint Petersburg, further cementing its influence on Russian art.

- 1903 – This year’s exhibition was another important showcase of the group’s creative output.

- 1906 – The final Mir Iskustva exhibition in Saint Petersburg was seen as an effort by Sergei Diaghilev to preserve unity within the group. At this time, there was growing tension between the Saint Petersburg and Moscow factions of the movement. The Moscow-based artists, frustrated with the group’s direction, had already organized the Exhibition of 36 Artists in 1901 and subsequently formed the Union of Russian Artists in 1903, a more conservative and traditionalist group. Diaghilev’s 1906 exhibition was an attempt to maintain cohesion, but it ultimately marked the group’s dissolution. [7]

In 1910, Mir iskustva was revived after Alexandre Benois published a critical article Rech' about the Union of Russian Artists. Nicholas Roerich became the new chairman, and the group expanded to include the avant -garde artists such as Nathan Altman, Vladimir Tatlin[8], and Martiros Saryan. Some said that the inclusion of Russian avant-garde painters demonstrated that the group had become an exhibition organization rather than an art movement. In 1917 the chairman of the group became Ivan Bilibin. The same year most members of the Jack of Diamonds entered the group.

1922 Saint-Petersburg, Moscow). The last exhibition of Mir iskusstva was organized in Paris in 1927. Some members of the group entered the Zhar-Tsvet (Moscow, organized in 1924) and Four Arts (Moscow-Leningrad, organized in 1925) artistic movements.

Art

Like the English Pre-Raphaelites before them, Benois and his colleagues were disgusted with anti-aesthetic nature of modern industrial society and modernity in general, and sought to consolidate all Neo-Romantic Russian artists under the banner of fighting Positivism in art. Their mission was to return to art's more expressive and idealizes roots, rejecting the rational and the mechanical.

Like the Romantics before them, the miriskusniki promoted understanding and conservation of the art of previous epochs, particularly traditional folk art and the 18th-century rococo. Antoine Watteau was probably the single artist whom they admired the most.

Such Revivalist projects were treated by the miriskusniki humorously, in a spirit of self-parody. They were fascinated with masks and marionettes, with carnaval and puppet theater, with dreams and fairy-tales. Everything grotesque and playful appealed to them more than the serious and emotional. Their favorite city was Venice, so much so that Diaghilev and Stravinsky selected it as the place of their burial

- Preferred Media

- The Mir Iskustva group favored light, airy media such as watercolor and gouache over traditional, heavy oil paintings.

- They aimed to bring art into everyday life, designing interiors and books.

- Revolutionary theatrical Design:

- Bakst and Benois transformed theatrical design with their groundbreaking work for productions like:

- Cléopâtre (1909)

- Carnaval (1910)

- Petrushka (1911)

- L'après-midi d'un faune (1912)

- Bakst and Benois transformed theatrical design with their groundbreaking work for productions like:

- Active members:

- In addition to the three founding members, prominent figures in Mir Iskustva included:

- Mstislav Dobuzhinsky

- Eugene Lansere

- Konstantin Somov

- In addition to the three founding members, prominent figures in Mir Iskustva included:

- Exhibitions and Influence:

- Mir Iskustva exhibitions attracted renowned painters from Russia and abroad, such as:

- Mikhail Vrubel

- Mikhail Nesterov

- Isaac Levitan

- Mir Iskustva exhibitions attracted renowned painters from Russia and abroad, such as:

In 1902, Benois and Mir Iskustva established a publishing house, producing a variety of materials aimed at bringing art and knowledge to a wider audience. They created postcards featuring reproductions of art masterpieces, as well as 'educational' postcards with short commentaries and images from various scientific fields, such as geography and zoology. However, these items saw limited demand, with only scenic and landscape postcards selling in large numbers.

By 1909, the publishing house shifted its focus to books, producing guidebooks on locations such as Pavlovsk, Saint Petersburg, and the Hermitage Museum. One of their most notable publications was an exquisite edition of The Bronze Horseman, illustrated by Benois. This marked a significant step in their goal of making art more accessible to the public. They published guide-books on Pavlovsk, St Petersburg, Hermitage Museum, an exquisite edition of The Bronze Horseman with illustrations by Benois and many more.[9]

Gallery

- Representative works

References

- ^ Grover, Stuart R. (1973-01). "The World of Art Movement in Russia". Russian Review. 32 (1): 28. doi:10.2307/128091.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Scholl, Tim (1994). From Petipa to Balanchine: classical revival and the modernization of ballet. Routledge. p. 66. ISBN 0415092221.

- ^ "Mir iskusstva | Russian magazine | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2025-02-21.

- ^ a b Melnik 2015, p. 205.

- ^ "Peredvizhniki | Realist, Impressionist & Naturalist | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2025-02-21.

- ^ a b Pyman, Avril (1994). A History of Russian Symbolism. Cambridge University Press. p. 121. ISBN 0521241987.

- ^ Grover, Stuart R. (1973-01). "The World of Art Movement in Russia". Russian Review. 32 (1): 28. doi:10.2307/128091.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Parton, Anthony; Milner, John (1984). "Vladimir Tatlin and the Russian Avant-Garde". Leonardo. 17 (3): 218. doi:10.2307/1575198. ISSN 0024-094X.

- ^ Mazokhina 2009, p. 163-167.

Literature

- Hanna Chuchvaha, Art Periodical Culture in Late Imperial Russia (1898-1917). Print Modernism in Transition (Boston & Leiden: Brill, 2016)

- Melnik, Natalya (2015). "On the History of the Establishing of 'Mir Iskusstva' in St Petersburg". SPSU Journal (in Russian). 3. Saint Petersburg State University: 203–215. Retrieved 2020-12-08.

- Yakovleva, A. S. (2017). "Aestheticism and decadence in articles of journal "World of art"". Journal of Saint-Petersburg State University of Culture and Arts (in Russian). 3 (32): 150–152. Retrieved 2020-12-08.

- Ilyina, T. V.; Fomina, M. S. (2018). История отечественного искусства [National Arts History] (in Russian). Moscow. p. 238. ISBN 978-5-534-07319-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Mazokhina, N. A. (2009). Издательский проект художников объединения "Мир искусства" [The Publishing project of the artists of the "World of Art" association]. Chelyabinsk State University Journal (in Russian). 34 (172): 163–167. Retrieved 2020-12-08.

- Janet Kennedy, The Mir Iskusstva Group and Russian Art 1898-1912 (New York: Garland, 1977)