Mike Quill

Mike Quill | |

|---|---|

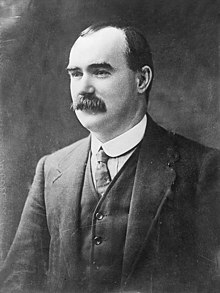

Mike Quill in 1938 | |

| Head of the Transport Workers Union of America | |

| In office c. 1936 – January 28, 1966 | |

| Member of the New York City Council | |

| In office January 1, 1938 – January 1, 1940 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Michael Joseph Quill September 18, 1905 Gortluchura Kilgarvan, County Kerry, Ireland |

| Died | January 28, 1966 (aged 60) New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Political party | American Labor |

| Spouses |

|

| Children | John Daniel Quill |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | Irish Republic |

| Branch/service | Irish Republican Army Anti-Treaty IRA |

| Years of service | 1919–1923 |

| Battles/wars | Irish War of Independence Irish Civil War |

Michael Joseph "Red Mike" Quill (September 18, 1905 – January 28, 1966) was one of the founders of the Transport Workers Union of America (TWU), a union founded by subway workers in New York City that expanded to represent employees in other forms of transit. He served as the President of the TWU for most of the first thirty years of its existence. A close ally of the Communist Party USA (CP) for the first twelve years of his leadership of the union, he broke with it in 1948.

Quill had varying relations with the mayors of New York City. He was a personal friend of Robert F. Wagner Jr. but could find no common ground with Wagner's successor, John Lindsay, or as Quill called him "Linsley", and led a twelve-day transit strike in 1966 against him that landed him in jail. However, he won significant wage increases for his members. He died of a heart attack three days after the end of the strike. Quill's leadership is not only noted for his success in improving workers' rights but also for his commitment to racial equality, before the Civil Rights Era.

Early years in Ireland and immigration to America

Quill was born in Gortloughera, near Kilgarvan, County Kerry, Ireland. He was a dispatch rider for the Irish Republican Army from 1919 to 1921 while still a teenager; then a volunteer of the Anti-Treaty IRA in the Irish Civil War that followed. One canard has him robbing a bank to raise funds for the IRA.[citation needed] He participated in fighting between Pro and Anti Treaty IRA units over the town of Kenmare in Kerry.[1] Quill's IRA record of service was confirmed by his commanding officer John Joe Rice, Kerry 2nd Brigade years later to Quill's widow Shirley.

Following the wars, Quill worked as a carpenter's apprentice, then a woodcutter. Having fought for the losing side in the Civil War, Quill's prospects in Ireland were low and so he was brought to the United States in 1926[2][3] by his uncle Patrick Quill, a conductor in the subway who got him his first job there. Mike's brothers, Patrick and John, had already moved to the city before him. In New York City, Quill first lived with family in Harlem.[3]

Working for the IRT and trade unionism

Quill worked various odd jobs to make ends meet, including at one point bootlegging alcohol, as prohibition was still in effect at the time.[4] Eventually by 1929 he returned to New York City where his uncle arranged for him a job with the Interborough Rapid Transit Company (IRT), first as a night gateman, then as a clerk or "ticket chopper". The job was a punishing one; Quilled worked 84 hours a week, 12 hours a night, seven nights a week for 33c an hour. At the time there was no sick leave, holidays, or pension rights.[1]

Moving from station to station, Quill got to know a large number of IRT employees, many of them also Irish immigrants. They would joke that IRT stood for "Irish Republican Transit" on account of how many of their peers were also Irish Republicans. It was during this time that Quill used the quiet of the late hours to read labor history and, in particular, the works of James Connolly.[4] Connolly had been a revolutionary and high profile labor activist in Ireland until his death in 1916 following the Easter Rising, an event that eventually sparked the two wars in which Quill had participated. Two of Connolly's thoughts came to guide Quill's political philosophy; the ideas that that economic power precedes and conditions political power, and that the only effective and satisfactory expression of the workers’ demands is to be found politically in a separate and independent labor party, and economically in the industrial union.[4][3]

In 1933 Quill, along with others such as fellow Irish immigrant and Irish Republican Thomas H. O'Shea, moved to create a Trade Union free and independent of the IRT's complacent company union. The name that Quill and others chose for their new union, the Transport Workers Union, was a tribute to the Irish Transport and General Workers Union led by Jim Larkin and Connolly twenty years earlier.[4] The new union was mainly compromised at its core of members of Clan na Gael, a secretive Irish-American organization that supported "physical force" Irish Republicanism, and members of the Communist Party USA, who supplied organizers, operating funds, and connections with organizations outside the Irish-American community.[5] The Communist Party was at that time in the last years of its ultrarevolutionary Third Period, when it sought to form revolutionary unions outside the American Federation of Labor. The party, therefore, focused both on organizing workers into the union and recruiting members for the Party through mimeographed shop papers with titles such as "Red Shuttle" or "Red Dynamo".

Another source of the core membership of what became the TWU were the Irish Workers' Clubs, setup by James Gralton who had been essentially exiled from Ireland for his left-wing political activities in 1933.[5][4]

Two Trade Union Unity League organizers, John Santo and Austin Hogan, met with the Clan na Gael's members in a cafeteria on Columbus Circle on April 12, 1934, the date now used to mark the foundation of the union. The new union appointed Thomas H. O'Shea as its first president, assigning Quill a secondary position. Quill proved to have more leadership potential than O'Shea, however, and quickly came to replace him in the top position.[1] He was a persuasive speaker, willing to "soapbox" outside of IRT facilities for hours, and capable of great charm in individual conversations.[3] He also acquired some renown after an incident in 1936, in which some "beakies", the informants used by the IRT to spy on union activities, attacked Quill and five other unionists in a tunnel as they were returning from picketing the IRT's offices. Arrested for inciting to riot, Quill came off as a fighter in his defence of the charges, which were eventually dismissed.

Quill was closely associated with the Communist Party from the outset but proved rebellious as well. When the Third Period gave way to the Popular Front era, Santo and Hogan directed O'Shea and Quill to abandon efforts to form a new union and to run instead for office in the IRT company union, the Interborough Brotherhood. Quill denounced the plan vociferously, to the point that he was nearly expelled from the union. Quill came around, however, by the next party meeting and began attending Brotherhood meetings — while still recruiting workers there to join the TWU.

Given the level of surveillance, and consistent with the conspiratorial traditions of Irish political movements, the union proceeded clandestinely, forming small groups of trusted friends in order to keep informers at bay, meeting in isolated locations and in subway tunnels. Those few workers, such as Quill, who were willing to accept identification as union activists also spread the word about the new union by handing out flyers and delivering soapbox speeches in front of company facilities.[3] After a year of organizing, the union formed a Delegates Council, made up of representatives from sections of the system.

In the meantime the new union continued its patient organizing campaign, conducting a number of brief strikes over workplace conditions, but avoiding any large-scale confrontations. That changed on January 23, 1937, when the Brooklyn–Manhattan Transit Corporation (BMT) fired two union members at the Kent Avenue powerhouse plant in Williamsburg, Brooklyn for union activity. The union launched a successful sitdown strike two days later that solidified the union's support among BMT employees, helped lead to its overwhelming victory in an NLRB-conducted election among the IRT's 13,500 employees later that year and helped bring thousands of other transit employees into the union.[3]

TWU leadership

In 1936, the TWU joined the International Association of Machinists to link itself to the AFL. On May 10, 1937, the TWU severed relations with the Machinists and joined the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) as a national union.[3]

The union soon faced challenges within, as dissidents within the union and the Association of Catholic Trade Unionists outside it challenged the CPUSA's dominant position within its officialdom and staff. The CP at that time had almost complete control over the union's administration and CP membership was necessary both to get a job with the union and to rise through its ranks. Former allies such as O'Shea attacked Quill and the CP, both in the publications of rival unions, such as the Amalgamated Association of Street Railway Employees, and in testimony before the Dies Committee.[4]

Quill and the union leadership gave their opponents all the ammunition they needed by following the changes in the CPUSA's foreign policy, moving to a militant policy after the Molotov–Ribbentrop pact in 1939, then coming out against strikes after the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941. Quill shrugged off most of this criticism from outside, haranguing the Dies Committee when it attempted to question him, and disposed of his internal critics by bringing union charges against more than a hundred opponents.

The union faced more serious challenges at home as Mayor Fiorello La Guardia threatened to revoke the union's status as the representative of the employees of the IRT and BMT when the City bought those lines in 1940. Quill had cooperated with La Guardia when the former ran, successfully, for City Council in 1937, as a candidate of the American Labor Party. In 1940, however, both La Guardia and Quill became bellicose opponents of each other, with Quill calling a bus drivers' strike that served to demonstrate the union's power if challenged while La Guardia came out in opposition to collective bargaining, the closed shop and the right to strike for public employees.

In 1941, the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union changed the Party's opinion of strikes, though it would be simplistic to treat this change in strategy solely as the result in the change in Comintern policy. Throughout his career, Quill preferred to threaten strikes as leverage to calling them and provoking a decisive test of strength. In addition, the union leadership had reservations in 1941 about the depth of its support among the general public and the employees of the IRT and BMT, many of whom believed that civil service protections gained as employees of the City made union representation less critical. National CIO leaders and the Franklin Delano Roosevelt administration intervened in 1941 to avert a subway strike with an ambiguous agreement that preserved TWU's right to represent its members, even though the City continued to deny it exclusive representation.

Breaking with the CP

The pressure on CP-led unions intensified after the end of World War II. These pressures fell especially hard on the TWU: the government arrested Santo for immigration law violations, and began proceedings to deport him. At the same time, Quill found the CP's political line increasingly hard to take, since it required him to oppose a subway fare increase that he considered necessary for wage increases in 1947, while the CP's support for the candidacy of Henry Wallace threatened to split the CIO. When William Z. Foster, then the general secretary of the CPUSA, told him that the party was prepared to split the CIO to form a third federation and that he might be the logical choice for its leader, Quill decided to break his ties to the CP instead.

Quill applied the same energy to his campaign to drive his former allies out of the union that he had during the union's organizing drives of the 1930s. He was able to enlist new Mayor of New York City William O'Dwyer (a native of County Mayo back in Ireland), to his support, winning a large wage increase for subway workers in 1948, thus cemented his standing with the membership. After a few inconclusive internal battles, Quill prevailed in 1949, purging not only the officers who had opposed him, but much of the union's staff, down to its secretarial employees.

Postwar years

Unlike some others, such as Joseph Curran of the National Maritime Union, "Red Mike" Quill remained on the left within the labor movement — albeit in a political atmosphere in which the boundaries had shifted drastically during the Cold War — after his split with the CP. Quill was the most vocal opponent within the CIO of its merger with the AFL, attacking it for "racism, racketeering and raids". He and the TWU were early supporters of the civil rights movement, and Quill publicly opposed the Vietnam War in the early 1960s.

Quill and the TWU became even more important figures in New York City politics in the 1950s. He was a key supporter of Robert F. Wagner, Jr.'s campaign for mayor of New York; Quill's former leadership of the Communist Party was repeatedly criticized during the campaign. While his union repeatedly threatened to strike, it reached collective-bargaining agreements with the Wagner administration without ever striking.

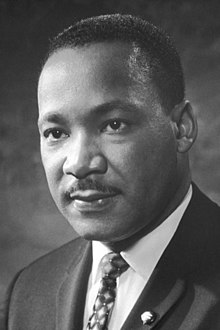

Support for racial equality and Martin Luther King

Quill had a longstanding distaste for racism and any other kind of discrimination. Beginning immediately in the 1930s with his ascension to the leadership of the TWU, he had made it a point not to tolerate any kind of racial discrimination under his watch. From the outset, the TWU vowed to support workers ‘regardless of race, creed, color or nationality’, making it an anomaly in the still racially segregated America and amongst other Trade Unions in New York City. The TWU matched their words with action in 1938 when the Union supported the rights of Black transit workers. At that time, Black workers could only work as either porters or cleaners, but the TWU forced the IRT to allow black workers to better positions within the company. In 1939 the TWU held the first desegregated trade union meeting in New Orleans since the Reconstruction era. In 1941 Quill pledged to fight to see that ‘the color-line is wiped out . . . and that the Negro and white workers will have equal rights in this country’. Two years later he spoke at dozens of workplace meetings in New York, warning of the consequences for all workers of the wave of race riots then occurring in the US. In 1945 the TWU ran a nationwide campaign against lynching.[6]

In the 1940s, Quill spoke out against the Anti-Semitism of Father Charles Coughlin, a Catholic Priest of Irish ethnicity who had become a sensation in the United States on the radio. "Anti-Semitism is not the problem of the Jewish people alone. It is an American problem, a number one American problem. We all know how Hitler came into power—while he was persecuting one section of the people, other sections of the people were asleep. The merchants of hate picked their spot and picked their cause. We too must pick our cause—freedom of all peoples in a democratic America.” said Quill in relation to Coughlin.[3]

From 1956 onwards the TWU had been organising financial and practical support for the movement against segregation. In 1960 the TWU established a fund to pay bail for those arrested for attempting to desegregate restaurants throughout the South. Its members took part in pickets, marches and rallies in support of the southern movement. In 1961 Martin Luther King was the guest speaker at the TWU convention.[2] Quill introduced King as "The man who is entrusted with the banner of American liberty that was taken from Lincoln when he was shot 95 years ago".[4][1] King's speech, ‘Segregation must die if democracy is to live’, was published in pamphlet form and sent to TWU branches across the United States with instructions from Quill that it be widely distributed and discussed. In July 1963, just prior to the March on Washington, Quill told his union’s membership that the battle for civil rights was the key question facing America. That same year the TWU contributed to a fund to aid King and others imprisoned in Birmingham, Alabama. In 1965 a large number of TWU members joined with King on the Selma to Montgomery marches in one of the pivotal moments of the civil rights era.[6]

Quill was quite the admirer of Martin Luther King, whom he saw as a spiritual successor of Abraham Lincoln. Speaking of King, Quill remarked:

We are reaching the turning point in America. I don’t think any leader since Abraham Lincoln has done as much to unite the American people, black and white, as Dr. King has done in the past fifteen years. His tactics are very similar to the tactics that we use in the trade union movement—the sit-down strike, the outright strike, the boycott. Dr. King adopted the methods of the great Mahatma Gandhi, who after a hundred years, freed the Indian people from Imperialism by his special and unusual tactics. We are anxious about this struggle. We are anxious that it be finished in our time.[3]

Final years

The TWU did not have the same good relationship with the administration of John V. Lindsay, a liberal Republican who had rebuked Quill shortly before taking office in 1966, as they had had with Mayor Wagner.[7][8] When the TWU's contract with the city expired and Lindsay did not immediately accede to the union's specific pay raise demands, Quill called a strike which lasted twelve days. The world's largest subway and bus systems, serving eight million people daily, came to a complete halt. The City obtained an injunction prohibiting the strike and succeeded in imprisoning Quill and seven other leaders of the TWU and the Amalgamated Association, which joined in the stoppage, for contempt of court. The labor lawyer Theodore W. Kheel mediated the agreement that ended the strike.

Quill did not waver, responding at a crowded press conference: "The judge can drop dead in his black robes!"[9] The union successfully held out for a sizeable wage increase for the union. Other unions followed suit demanding similar raises.

Quill died at age 60, three days after the union's victory celebration. He had an initial heart attack when he was sent to jail for contempt. He was interred at Gate of Heaven Cemetery in Hawthorne, New York, after a funeral Mass at St. Patrick's Cathedral, his casket draped by the Irish tricolor.

Speaking after his death, Martin Luther King eulogised Quill with the following:

Mike Quill was a fighter for decent things all his life—Irish independence, labor organization, and racial equality. He spent his life ripping the chains of bondage off his fellow-man. When the totality of a man’s life is consumed with enriching the lives of others, this is a man the ages will remember—this is a man who has passed on but who has not died. Negroes had desperately needed men like Mike Quill who fearlessly said what was true even when it offended. That is why Negroes shall miss Mike Quill[6]

Family

Quill fathered a son, John Daniel Quill (named after Quill's own father), with his first wife Maria Theresa (Molly) O'Neill, who died before him. His second wife, Shirley Quill, survived him.[citation needed]

See also

- Communist Party USA and American labor movement (1919–1937)

- Communist Party USA and American labor movement (1937–1950)

- Michael J. Quill Bus Depot

- Union Organizer

References

- ^ a b c d Dwyer, Ryle (January 26, 2016). "Mike Quill: The Irishman Martin Luther King described as 'a man the ages will remember'". Retrieved September 21, 2020.

- ^ a b "Quill, Michael Joseph". Retrieved September 21, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i McEvoy, Dermot (February 25, 2018). "Mike Quill: America's greatest Irish-born hero?". Retrieved September 21, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g Rooney, Kevin (January 29, 2020). "Irish Republican, Socialist, Anti-Racist, Trade Union Founder: Michael J. Quill". Retrieved September 21, 2020.

- ^ a b White, Lawrence William. "Quill, Michael Joseph". Dictionary of Irish Biography. Retrieved September 21, 2020.

- ^ a b c Hanley, Brian (2004). "'A man the ages will remember': Mike Quill, the TWU and civil rights". Retrieved September 21, 2020.

- ^ Schlegel, Harry (November 29, 1965). "Quill Blasts Lindsay's Panel and Vacation". New York Daily News. pp. 3, 20. Retrieved July 16, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Mike Quill, 60, Dies; Headed TWU 31 Years". The Post-Star (Glens Falls, New York). United Press International. January 29, 1966. p. 1. Retrieved July 16, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Mallon, Jack; Mulligan, Arthur (January 5, 1966). "TA to Up Ante; Quill Stricken". New York Daily News. p. 3. Retrieved July 16, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

Further reading

- Freeman, Joshua B., In Transit: The Transport Workers Union in New York City, 1933–1966, New York: Oxford University Press, 1989.

- Quill, Shirley, Mike Quill, Himself : a Memoir, Greenwich, Connecticut: Devin-Adair, 1985

- Whittemore, L.H., The Man Who Ran the Subways; The Story of Mike Quill, New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1968