Megalocnidae

| Megalocnidae Temporal range: | |

|---|---|

| |

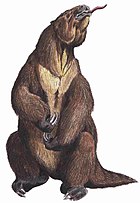

| Megalocnus rodens, an extinct Cuban megalocnid sloth (AMNH) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Pilosa |

| Suborder: | Folivora |

| Family: | †Megalocnidae White and MacPhee, 2001 |

| Genera | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Megalocnoidea Delsuc et al, 2019 | |

Megalocnidae is an extinct family (alternatively considered to be a superfamily as Megalocnoidea) of sloths, native to the islands of the Greater Antilles from the Early Oligocene to the Mid-Holocene. They are known from Cuba, Hispaniola and Puerto Rico, but are absent from Jamaica. While they were formerly placed in the Megalonychidae alongside two-toed sloths and ground sloths like Megalonyx, recent mitochondrial DNA and collagen sequencing studies place them as the earliest diverging group basal to all other sloths.[1][2] or as an outgroup to Megatherioidea.[3] They displayed significant diversity in body size and lifestyle, with Megalocnus being terrestrial and probably weighing several hundred kilograms, while Neocnus was likely arboreal and similar in weight to extant tree sloths, at less than 10 kilograms.[4]

Origin

It is thought that sloths arrived in the Caribbean from South America (where they arose) around the Eocene-Oligocene boundary about 33 million years ago, when there was a significant sea level drop caused by a glaciation episode.[5] This has been associated with the GAARlandia (Greater Aves Antilles Ridge) hypothesis, where the Aves Ridge is suggested to have formed a land bridge during the interval, allowing overland migration into the Greater Antilles. The existence of such a land bridge has been questioned because of the lack of geological evidence for the Aves Ridge having been subaerially exposed[6] as well as the fact that many other South American animals (such as marsupials and ungulates) are absent from the Greater Antilles, making a complete land bridge unlikely.[7][4][note 1] The earliest evidence suggesting the presence of sloths in the Caribbean is a partial femur from the Early Oligocene of Puerto Rico.[8] Other pre-Pleistocene fossil remains include Imagocnus from the Early Miocene of Cuba,[9] and an indeterminate species from the Late Miocene of the Dominican Republic.[10]

Description

Megalocnid sloths were relatively small compared to mainland ground sloths,[11] though they were the largest mammals native to the Caribbean islands[4] with the largest species Megalocnus rodens estimated to weigh around 146 kilograms (322 lb)[11] or 270 kilograms (600 lb),[4] with the smallest genera Neocnus and Acratocnus estimated to only weigh 8–15 kilograms (18–33 lb). [11]

Ecology

Like other sloths megalocnids were probably folivores, with some authors suggesting that based on the anatomy of their limbs, that Neocnus and Acratocnus were likely climbing animals.[11]

Taxonomy

The taxonomy of Caribbean sloths is in flux, with the number of species present among the Pleistocene-Holocene taxa in question; some species are likely junior synonyms, while the diversity of some genera is probably understated.[12] The mitochondrial DNA study suggests that Acratocnus ye and Parocnus serus are deeply divergent from each other, having split during the Oligocene, suggesting an early radiation within the group. An alternative taxonomy of the group has been proposed including the families Acratocnidae and Parocnidae within a new superfamily, Megalocnoidea.[1]

Based on White and MacPhee (2001):[13] and Vinola-Lopez et al. 2022[10]

- Megalocnus

- †M. rodens Pleistocene to Holocene, Cuba

- Acratocnus

- †A. odontrigonus Pleistocene, Puerto Rico

- †A. ye Pleistocene to Holocene, Hispaniola

- †A. antillensis Pleistocene to Holocene, Cuba

- Mesocnus

- †Mesocnus browni Pleistocene to Holocene, Cuba

- Parocnus

- Neocnus

- †N. gliriformis Pleistocene to Holocene, Cuba

- †N. major Pleistocene to Holocene, Cuba

- †N. comes Pleistocene to Holocene, Hispaniola

- †N. dousman Pleistocene to Holocene, Hispaniola

- †N. toupiti Pleistocene to Holocene, Hispaniola

- Imagocnus

- †I. zazae Early Miocene of Cuba

For other sloth taxa of the Caribbean, see Pilosans of the Caribbean.

Phylogeny

The following sloth family phylogenetic tree is based on collagen and mitochondrial DNA sequence data (see Fig. 4 of Presslee et al., 2019).[2]

| Folivora |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Extinction

Sloths in the Caribbean survived about 5,000 years longer than ground sloths on the mainland. On Cuba the latest date for Megalocnus is calibrated 4700 years Before Present (BP). approximately 2700 BC.[15] while dates for Parocnus browni are around 6250 BP (4250 BC). On Hispaniola the dates for some indeterminate sloth specimens are around 5000 BP (3000 BC); these dates roughly coincide with the first settlement of the Caribbean, which suggests that humans were the cause of the extinction.[16] Remains of Caribbean sloths have been found in a number of archaeological sites suggesting that they may have been consumed by the earliest inhabitants of the Caribbean, although evidence of hunting is inconclusive.[17]

Notes

- ^ The main groups of terrestrial mammals to colonize the Antilles, sloths, caviomorph rodents and platyrrhine monkeys, have all displayed a facility for oceanic dispersal or island hopping in other settings. For example, megalonychid and mylodontid ground sloths reached North America from South America prior to formation of a complete land bridge, and both caviomorphs and platyrrhines originally reached South America by rafting across the Atlantic from Africa.

References

- ^ a b Delsuc, F.; Kuch, M.; Gibb, G.C.; Karpinski, E.; Hackenberger, D.; Szpak, P.; Martínez, J.G.; Mead, J.I.; McDonald, H.G.; MacPhee, R.D.E.; Billet, G. (June 2019). "Ancient Mitogenomes Reveal the Evolutionary History and Biogeography of Sloths". Current Biology. 29 (12): 2031–2042.e6. Bibcode:2019CBio...29E2031D. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2019.05.043. hdl:11336/136908. PMID 31178321.

- ^ a b Presslee, S.; Slater, G.J.; Pujos, F.; Forasiepi, A.M.; Fischer, R.; Molloy, K.; Mackie, M.; Olsen, J.V.; Kramarz, A.; Taglioretti, M.; Scaglia, F. (July 2019). "Palaeoproteomics resolves sloth relationships". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 3 (7): 1121–1130. Bibcode:2019NatEE...3.1121P. doi:10.1038/s41559-019-0909-z. PMID 31171860. S2CID 174813630.

- ^ Tejada, Julia V; Antoine, Pierre-Olivier; Münch, Philippe; Billet, Guillaume; Hautier, Lionel; Delsuc, Frédéric; Condamine, Fabien L (2023-12-02). Wright, April (ed.). "Bayesian Total-Evidence Dating Revisits Sloth Phylogeny and Biogeography: A Cautionary Tale on Morphological Clock Analyses". Systematic Biology. 73 (1): 125–139. doi:10.1093/sysbio/syad069. ISSN 1063-5157. PMC 11129595. PMID 38041854.

- ^ a b c d Defler, Thomas (2019), "Mammalian Invasion of the Caribbean Islands", History of Terrestrial Mammals in South America, Topics in Geobiology, vol. 42, Springer International Publishing, pp. 221–234, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-98449-0_11, ISBN 978-3-319-98448-3, OCLC 1086356172, S2CID 134438659

- ^ Houben, A.J.P.; van Mourik, C.A.; Montanari, A.; Coccioni, R.; Brinkhuis, H. (June 2012). "The Eocene–Oligocene transition: Changes in sea level, temperature or both?". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 335–336: 75–83. Bibcode:2012PPP...335...75H. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2011.04.008.

- ^ Ali, Jason R. (March 2012). "Colonizing the Caribbean: is the GAARlandia land-bridge hypothesis gaining a foothold?: Commentary". Journal of Biogeography. 39 (3): 431–433. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2699.2011.02674.x. S2CID 84576035.

- ^ Ali, Jason R.; Hedges, S. Blair (November 2021). Hoorn, Carina (ed.). "Colonizing the Caribbean: New geological data and an updated land-vertebrate colonization record challenge the GAARlandia land-bridge hypothesis". Journal of Biogeography. 48 (11): 2699–2707. Bibcode:2021JBiog..48.2699A. doi:10.1111/jbi.14234. ISSN 0305-0270. S2CID 238647106.

- ^ MacPhee, R.D.E.; Iturralde-Vinent, M.A. (1995). "Origin of the Greater Antillean land mammal fauna, 1: New Tertiary fossils from Cuba and Puerto Rico". American Museum Novitates (3141): 1–31. hdl:2246/3657.

- ^ MacPhee, R.D.E.; Iturralde-Vinent, M.A. & Gaffney, E.S. (2003). "Domo de Zaza, an early Miocene vertebrate locality in south-central Cuba, with notes on the tectonic evolution of Puerto Rico and the Mona Passage". American Museum Novitates (3394): 1–42. doi:10.1206/0003-0082(2003)394<0001:DDZAEM>2.0.CO;2. hdl:2246/2820. S2CID 55615855.

- ^ a b Viñola-Lopez, Lazaro W.; Suárez, Elson E. Core; Vélez-Juarbe, Jorge; Milan, Juan N. Almonte; Bloch, Jonathan I. (May 2022). "The oldest known record of a ground sloth (Mammalia, Xenarthra, Folivora) from Hispaniola: evolutionary and paleobiogeographical implications". Journal of Paleontology. 96 (3): 684–691. Bibcode:2022JPal...96..684V. doi:10.1017/jpa.2021.109. ISSN 0022-3360. S2CID 245401150.

- ^ a b c d McDonald, H. Gregory (2023-06-06). "A Tale of Two Continents (and a Few Islands): Ecology and Distribution of Late Pleistocene Sloths". Land. 12 (6): 1192. doi:10.3390/land12061192. ISSN 2073-445X.

- ^ a b McAfee, R.K.; Beery, S.M. (2019-06-04). "Intraspecific variation of Megalonychid sloths from Hispaniola and the taxonomic implications". Historical Biology. 33 (3): 371–386. doi:10.1080/08912963.2019.1618294. S2CID 195403443.

- ^ White, J.L.; MacPhee, R.D.E. (2001). "The sloths of the West Indies: a systematic and phylogenetic review". In Woods, C. A.; Sergile, F. E. (eds.). Biogeography of the West Indies: Patterns and Perspectives. Boca Raton, London, New York, and Washington, D.C.: CRC Press. pp. 201–235. doi:10.1201/9781420039481-14. ISBN 978-0-8493-2001-9.

- ^ McAfee, Robert; Beery, Sophia; Rimoli, Renato; Almonte, Juan; Lehman, Phillip; Cooke, Siobhan (2021-08-31). "New species of the ground sloth Parocnus from the late Pleistocene-early Holocene of Hispaniola". Vertebrate Anatomy Morphology Palaeontology. 9 (1). doi:10.18435/vamp29369. ISSN 2292-1389.

- ^ MacPhee, R. D. E.; Iturralde-Vinent, M. A.; Vázquez, Osvaldo Jiménez (January 2007). "Prehistoric Sloth Extinctions in Cuba: Implications of a New "Last" Appearance Date". Caribbean Journal of Science. 43 (1): 94–98. doi:10.18475/cjos.v43i1.a9. ISSN 0008-6452. S2CID 56003217.

- ^ Steadman, D. W.; Martin, P. S.; MacPhee, R. D. E.; Jull, A. J. T.; McDonald, H. G.; Woods, C. A.; Iturralde-Vinent, M.; Hodgins, G. W. L. (2005-08-16). "Asynchronous extinction of late Quaternary sloths on continents and islands". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 102 (33): 11763–11768. Bibcode:2005PNAS..10211763S. doi:10.1073/pnas.0502777102. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 1187974. PMID 16085711.

- ^ Orihuela, Johanset; Viñola, Lázaro W.; Jiménez Vázquez, Osvaldo; Mychajliw, Alexis M.; Hernández de Lara, Odlanyer; Lorenzo, Logel; Soto-Centeno, J. Angel (December 2020). "Assessing the role of humans in Greater Antillean land vertebrate extinctions: New insights from Cuba". Quaternary Science Reviews. 249: 106597. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2020.106597.