Matsya

| Matsya | |

|---|---|

| Member of Dashavatara | |

Matsya avatar in British Museum, 1820 | |

| Devanagari | मत्स्य |

| Affiliation | Avatar of Vishnu |

| Mantra | Om Namo Bhagavate Matsya Devaya |

| Weapon | Sudarshana Chakra, Kaumodaki |

| Festivals | Matsya Jayanti |

| Consort | Lakshmi[1] |

| Dashavatara Sequence | |

|---|---|

| Predecessor | - |

| Successor | Kurma |

Matsya (Sanskrit: मत्स्य, lit. 'fish') is the fish avatar of the Hindu god Vishnu.[2] Often described as the first of Vishnu's ten primary avatars, Matsya is described to have rescued the first man, Manu, from a great deluge.[3] Matsya may be depicted as a giant fish, often golden in color, or anthropomorphically with the torso of Vishnu connected to the rear half of a fish.

The earliest account of Matsya is found in the Shatapatha Brahmana, where Matsya is not associated with any particular deity. The fish-saviour later merges with the identity of Brahma in post-Vedic era, and still later, becomes regarded with Vishnu. The legends associated with Matsya expand, evolve, and vary in Hindu texts. These legends have embedded symbolism, where a small fish with Manu's protection grows to become a big fish, and the fish saves the man who would be the progenitor of the next race of mankind.[4] In later versions, Matsya slays a demon named Hayagriva who steals the Vedas, and thus is lauded as the saviour of the scriptures.[5]

The tale is ascribed with the motif of flood myths, common across cultures.

Etymology

The deity Matsya derives his name from the word matsya (Sanskrit: मत्स्य), meaning "fish".[6] Monier-Williams and R. Franco suggest that the words matsa and matsya, both meaning fish, derive from the root mad, meaning "to rejoice, be glad, exult, delight or revel in". Thus, matsya means the "joyous one".[7][8][9] The Sanskrit grammarian and etymologist Yaska (c. 600 BCE) also refers to the same stating that fish are known as matsya as "they revel in eating each other". Yaska also offers an alternate etymology of matsya as "floating in water" derived from the roots syand (to float) and madhu (water).[10] The Sanskrit word matsya is cognate with Prakrit maccha ("fish").[11]

Legends and scriptural references

Vedic origins

The section 1.8.1 of the Shatapatha Brahmana (Yajur veda) is the earliest extant text to mention Matsya and the flood myth in Hinduism. It does not associate the fish Matsya with any other deity in particular.[13][14][15]

The central characters of this legend are the fish (Matsya) and Manu. The character Manu is presented as the legislator and ancestor king. One day, water is brought to Manu for his ablutions. In the water is a tiny fish. The fish states that it fears being swallowed by a larger fish and appeals to Manu to protect it.[15] In return, the fish promises to rescue Manu from an impending flood. Manu accepts the request. He puts the fish in a pot of water where it grows. Then he prepares a ditch filled with water, and transfers it there where it can grow freely. Once the fish grows further to be big enough to be free from danger, Manu transfers it into the ocean.[15][16] The fish thanks him, tells him the timing of the great flood, and asks Manu to build a ship by that day, one he can attach to its horn. On the predicted day, Manu visits the fish with his boat. The devastating floods come. Manu ties the boat to the horn. The fish carries the boat with Manu to the high grounds of the northern mountains (interpreted as the Himalayas). The lone survivor Manu then re-establishes life by performing austerities and yajna (sacrifices). The goddess Ida appears from the sacrifice and both together initiate the race of Manu, the humans.[15][17][18][19]

| Part of a series on |

| Vaishnavism |

|---|

|

According to Bonnefoy, the Vedic story is symbolic. The little fish alludes to the Indian "law of the fishes", an equivalent to the "law of the jungle".[15] The small and weak would be devoured by the big and strong, and needs the dharmic protection of the legislator and king Manu to enable it to attain its full potential and be able to help later. Manu provides the protection, the little fish grows to become big and ultimately saves all existence. The boat that Manu builds to get help from the saviour fish, states Bonnefoy, is symbolism of the means to avert complete destruction and for human salvation. The mountains represent the doorway for ultimate refuge and liberation.[15] Edward Washburn Hopkins suggests that the favour of Manu rescuing the fish from death, is reciprocated by the fish.[13]

Though Matsya does not appear in older scriptures,[20][21] the seeds of the legend may be traced to the oldest Hindu scripture, the Rigveda. Manu (lit. "man"), the first man and progenitor of humanity, appears in the Rigveda. Manu is said to have performed the first sacrifice by kindling the sacrificial fire (Agni) with seven priests; Manu's sacrifice becomes the archetypal sacrifice.[21] Narayan Aiyangar suggests that the ship from the Matsya legend alludes to the ship of Sacrifice referred in the Rigveda and the Aitareya Brahmana. In this context, the fish denotes Agni - God as well as the sacrificial flames. The legend thus signifies how man (Manu) can sail the sea of sins and troubles with the ship of sacrifice and the fish-Agni as his guide.[22]

In a prayer to kushta plant in the Atharvaveda, a golden ship is said to rest at a Himalayan peak, where the herb grows. Maurice Bloomfield suggests that this may be an allusion to Manu's ship.[23]

Saviour of Manu from the Deluge

The tale of Matsya also appears in sec. 186 of Book 3 (the Vana Parva) of the epic Mahabharata.[25][15] The legend begins with Manu (specifically Vaivasvata Manu, the present Manu. Manu is envisioned as a title, rather than an individual) performing religious rituals on the banks of the Chirini River in Vishāla forest. A little fish comes to him and asks for his protection, promising to save him from a deluge in the future.[14] The legend moves in the same vein as the Vedic version. Manu places him in the jar. Once it outgrows the jar, the fish asks to be put into a tank which Manu helps with. Then the fish outgrows the tank, and with Manu's help reaches the Ganges River (Ganga), finally to the ocean. Manu is asked by the fish, as in the Shatapatha Brahmana version, to build a ship and additionally, to be in it with Saptarishi (seven sages) and all sorts of seeds, on the day of the expected deluge.[14][15] Manu accepts the fish's advice. The deluge begins. The fish arrives to Manu's aid. He ties the ship with a rope to the horn of the fish, who then steers the ship to the Himalayas, carrying Manu through a turbulent storm. The danger passes. The fish then reveals himself as Brahma and gives the power of creation to Manu.[14][26][27]

The key difference between the Vedic version and the Mahabharata version of the allegorical legend are the latter's identification of Matsya with Brahma, a more explicit discussion of the "law of the fishes" where the weak needs the protection from the strong, and the fish asking Manu to bring along sages and grains.[15][16][28]

The Matsya Purana identifies the fish-savior (Matsya) with Vishnu, instead of Brahma.[29] The Purana derives its name from Matsya and begins with the tale of Manu.[note 1] King Manu renounces the world. Pleased with his austerities on Malaya mountains (interpreted as Kerala in Southern India[32]), Brahma grants his wish to rescue the world at the time of the pralaya (dissolution at end of a kalpa).[note 2] As in other versions, Manu encounters a little fish that miraculously increases in size over time and soon he transfers the fish to the Ganges and later to the ocean.[33] Manu recognizes the fish as Vishnu. The fish warns him about the impending fiery end of kalpa accompanied with the pralaya as a deluge. The fish once again has a horn, but the gods gift a ship to Manu. Manu carries all types of living creatures and plant seeds to produce food for everyone after the deluge is over. When the great flood begins, Manu ties the cosmic serpent Shesha to the fish's horn. In the journey towards the mountains, Manu asks questions to Matsya and their dialogue constitutes the rest of the Purana.[29][34][35]

The Matsya Purana story is also symbolic. The fish is divine to begin with, and needs no protection, only recognition and devotion. It also ties the story to its cosmology, connecting two kalpas through the cosmic symbolic residue in the form of Shesha.[29] In this account, the ship of Manu is called the ship of the Vedas, thus signifying the rites and rituals of the Vedas. Roy further suggests that this may be an allusion to the gold ship of Manu in the Rigveda.[36]

In the Garuda Purana, Matsya is said to have rescued the seventh Manu, Vaivasvata Manu, from the great deluge by placing him in a boat.[37] The Linga Purana praises Vishnu as the one who saved various beings as a fish by tying a boat to his tail.[38]

Saviour of the Vedas

The Bhagavata Purana adds another reason for the Matsya avatar. At the end of the kalpa, a demon Hayagriva ("horse-necked") steals the Vedas, which escape from the yawn of a sleepy Brahma. Vishnu discovers the theft. He descends to earth in the form of a little saphari fish, or the Matsya avatar. One day, the king of Dravida country (South India) named Satyavrata cups water in his hand for libation in the Kritamala river (identified with Vaigai River in Tamil Nadu, South India[39]). There he finds a little fish. The fish asks him to save him from predators and let it grow. Satyavrata is filled with compassion for the little fish. He puts the fish in a pot, from there to a well, then a tank, and when it outgrows the tank, he transfers the fish finally to the sea. The fish rapidly outgrows the sea. Satyavrata asks the supernatural fish to reveal its true identity, but soon realizes it to be Vishnu. Matsya-Vishnu informs the king of the impending flood coming in seven days. The king is asked to collect every species of animal, plant, and seeds as well as the seven sages (Saptarshi) in a boat. The fish asks the king to tie the boat to its horn with the help of the Shesha serpent. The deluge comes. While carrying them to safety, the fish avatar teaches the highest knowledge to the sages and Satyavrata to prepare them for the next cycle of existence. The Bhagavata Purana states that this knowledge was compiled as a Purana, interpreted as an allusion to the Matsya Purana.[40] After the deluge, Matsya slays the demon and rescues the Vedas, restoring them to Brahma, who has woken from his sleep to restart creation afresh. Satyavrata becomes Vaivasvata Manu and is installed as the Manu of the current kalpa.[41][42][43]

The Agni Purana narrative is similar to the Bhagavata Purana version placed around Kritamala river and also records the rescue of Vedas from the demon Hayagriva. It mentions Vaivasvata Manu only collecting all seeds (not living beings) and assembling the seven sages similar to the Mahabharata version. It also adds the basis of the Matsya Purana, being the discourse of Matsya to Manu, similar to the Bhagavata Purana version.[44][45] While listing the Puranas, the Agni Purana states that the Matsya Purana was told by Matsya to Manu at the beginning of the kalpa.[46]

The Varaha Purana equates Narayana (identified with Vishnu) as the creator-god, instead of Brahma. Narayana creates the universe. At the start of a new kalpa, Narayana wakes from his slumber and thinks about the Vedas. He realizes that they are in the cosmic waters. He takes the form of a gigantic fish and rescues the Vedas and other scriptures.[47] In another instance, Narayana retrieves the Vedas from the Rasatala (netherworld) and grants them to Brahma.[48] The Purana also extols Narayana as the primordial fish who also bore the earth.[49] PPL

The Garuda Purana states that Matsya slew Hayagriva and rescued the Vedas as well as the Manu.[50] In another instance, it states that Vishnu as Matsya killed the demon Pralamba in the reign of the third Manu - Uttama.[51] The Narada Purana states that the demon Hayagriva (son of Kashyapa and Diti) seized the Vedas of the mouth of Brahma. Vishnu then takes the Matsya form and kills the demon, retrieving the Vedas. The incident is said to have happened in the Badari forest. The deluge and Manu are dropped in the narrative.[52] The Shiva Purana praises Vishnu as Matsya who rescued the Vedas via king Satyavrata and swam through the ocean of pralaya.[53]

The Padma Purana replaces Manu with the sage Kashyapa, who finds the little fish who expands miraculously. Another major divergence is the absence of the deluge. Vishnu as Matsya slays the demon Shankha. Matsya-Vishnu then orders the sages to gather the Vedas from the waters and then presents the same to Brahma in Prayag. This Purana does not reveal how the scriptures drowned in the waters. Vishnu then resides in the Badari forest with other deities.[54] The Karttikamsa-Mahatmya in the Skanda Purana narrates that slaying of the asura (demon) Shankha by Matsya. Shankha (lit. "conch"), the son of Sagara (the ocean), snatches the powers of various gods. Shankha, wishing to acquire more power, steals the Vedas from Brahma, while Vishnu was sleeping. The Vedas escape from his clutches and hide in the ocean. Implored by the gods, Vishnu wakes on Prabodhini Ekadashi and takes the form of a saphari fish and annihilates the demon. Similar to the Padma Purana, the sages re-compile the scattered Vedas from the oceans. The Badari forest and Prayag also appear in this version, though the tale of growing fish and Manu is missing.[55]

Another account in the Padma Purana mentions that a demon son called Makara steals the Vedas from Brahma and hides them in the cosmic ocean. Beseeched by Brahma and the gods, Vishnu takes the Matsya-form and enters the waters, then turns into a crocodile and destroys the demon. The sage Vyasa is credited with re-compilation of the Vedas in this version. The Vedas are then returned to Brahma.[56]

The Brahma Purana states that Vishnu took the form of a rohita fish when the earth was in the netherland to rescue the Vedas.[57][58] The Krishna-centric Brahmavaivarta Purana states that Matsya is an avatar of Krishna (identified with Supreme Being) and in a hymn to Krishna praises Matsya as the protector of the Vedas and Brahmins (the sages), who imparted knowledge to the king.[59]

The Purusottama-Ksetra-Mahatmya of Skanda Purana in relationship of the origin of the herb Damanaka states that a daitya (demon) named Damanaka tormented people and wandered in the waters. On the request of Brahma, Vishnu takes the Matsya form, pulls the demon from the waters and crushes him on land. The demon transforms into a fragrant herb called Damanaka, which Vishnu wears in his flower garland.[60]

In avatar lists

Matsya is generally enlisted as the first avatar of Vishnu, especially in Dashavatara (ten major avatars of Vishnu) lists.[61] However, that was not always the case. Some lists do not list Matsya as first, and only later texts start the trend of Matsya as the first avatar.[34]

In the Garuda Purana listing of the Dashavatara, Matsya is the first.[62][63] The Linga Purana, the Narada Purana, the Shiva Purana, the Varaha Purana, the Padma Purana, the Skanda Purana also mention Matsya as the first of the ten classical avatars.[64][65][66][53][67][68]

The Bhagavata Purana and the Garuda Purana regard Matsya as the tenth of 22 avatars and describe him as the "support of the earth".[69][37]

The Ayidhya-Mahatmya of the Skanda Purana mentions 12 avatars of Vishnu, with Matsya as the 2nd avatar. Matsya is said to support Manu, plants and others like a boat at the end of Brahma's day (pralaya).[70]

Other scriptural references

The Vishnu Purana narrative of Vishnu's boar avatar Varaha alludes to the Matsya and Kurma avatars, saying that Brahma (identified with Narayana, an epithet transferred to Vishnu) took these forms in previous kalpas.[71]

The Agni Purana, the Brahma Purana and the Vishnu Purana suggests that Vishnu resides as Matsya in Kuru-varsha, one of the regions outside the mountains surrounding Mount Meru.[72][73][74]

Iconography

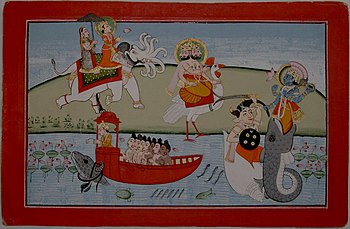

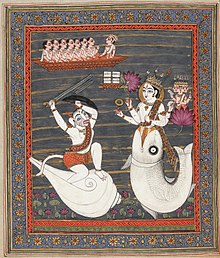

Matsya is depicted in two forms: as a zoomorphic fish or in an anthropomorphic form. The Agni Purana prescribes Matsya be depicted zoomorphically.[75] The Vishnudharmottara Purana recommends that Matsya be depicted as horned fish.[76]

In the anthropomorphic form, the upper half is that of the four-armed man and the lower half is a fish. The upper half resembles Vishnu and wears the traditional ornaments and the kirita-mukuta (tall conical crown) as worn by Vishnu. He holds in two of his hands the Sudarshana chakra (discus) and a shankha (conch), the usual weapons of Vishnu. The other two hands make the gestures of varadamudra, which grants boons to the devotee, and abhayamudra, which reassures the devotee of protection.[77] In another configuration, he might have all four attributes of Vishnu, namely the Sudarshana chakra, a shankha, a gada (mace) and a lotus.[34]

In some representations, Matsya is shown with four hands like Vishnu, one holding the chakra, another the shankha, while the front two hands hold a sword and a book signifying the Vedas he recovered from the demon. Over his elbows is an angavastra draped, while a dhoti-like draping covers his hips.[78]

In rare representations, his lower half is human while the upper body (or just the face) is of a fish. The fish-face version is found in a relief at the Chennakesava Temple, Somanathapura.[79]

Matsya may be depicted alone or in a scene depicting his combat with a demon. A demon called Shankhasura emerging from a conch is sometimes depicted attacking Matsya with a sword as Matsya combats or kills him. Both of them may be depicted in the ocean, while the god Brahma and/or manuscripts or four men, symbolizing the Vedas, may be depicted in the background.[78] In some scenes, Matsya is depicted as a fish pulling the boat with Manu and the seven sages in it.

Evolution and symbolism

The story of a great deluge is found in many civilizations across the earth. It is often compared with the Genesis narrative of the flood and Noah's Ark.[34] The fish motif reminds readers of the Biblical 'Jonah and the Whale' narrative as well; this fish narrative, as well as the saving of the scriptures from a demon, are specifically Hindu traditions of this style of the flood narrative.[80] Similar flood myths also exist in tales from ancient Sumer and Babylonia, Greece, the Maya of Americas and the Yoruba of Africa.[34]

The flood was a recurring natural calamity in Ancient Egypt and Tigris–Euphrates river system in ancient Babylonia. A cult of fish-gods arose in these regions with the fish-saviour motif. While Richard Pischel believed that fish worship originated in ancient Hindu beliefs, Edward Washburn Hopkins rejected the same, suggesting its origin in Egypt. The creator, fish-god Ea in the Sumerian and Babylonian version warns the king in a dream of the flood and directs him to build a boat.[81] The idea may have reached the Indian subcontinent via the Indo-Aryan migrations or through trade routes to the Indus Valley civilisation.[82] Another theory suggests the fish myth is home-grown in the Indus Valley or South India Dravidian peoples. The Puranic Manu is described to be in South India. As for Indus Valley theory, the fish is common in the seals; also horned beasts like the horned fish are common in depictions.[83]

Even if the idea of the flood myth and the fish-god may be imported from another culture, it is cognate with the Vedic and Puranic cosmogonic tale of Creation through the waters. In the Mahabharata and the Puranas, the flood myth is in fact a cosmogonic myth. The deluge symbolizes dissolution of universe (pralaya); while Matsya "allegorizes" the Creator-god (Brahma or Vishnu), who recreates the universe after the great destruction. This link to Creation may be associated with Matsya regarded as Vishnu's first avatar.[84]

Matsya is believed to symbolise the aquatic life as the first beings on earth.[85][34] Another symbolic interpretation of the Matsya mythology is, states Bonnefoy, to consider Manu's boat to represent moksha (salvation), which helps one to cross over. The Himalayas are treated as a boundary between the earthly existence and land of salvation beyond. The protection of the fish and its horn represent the sacrifices that help guide Manu to salvation. Treated as a parable, the tale advises a good king should protect the weak from the mighty, reversing the "law of fishes" and uphold dharma, like Manu, who defines an ideal king.[15] In the tales where the demon hides the Vedas, dharma is threatened and Vishnu as the divine Saviour rescues dharma, aided by his earthly counterpart, Manu - the king.[29]

Another theory suggests that the boat of Manu and the fish represents the constellations of Ursa Major and Ursa Minor respectively, when the star Thuban was the Pole Star (4th to 2nd millennium BCE).[36]

Worship

Matsya is invoked as a form of Vishnu in various hymns in scriptures. In a prayer in the Bhagavata Purana, Matsya is invoked for protection from the aquatic animals and the waters.[86] The Agni Purana suggests that Matsya be installed in the Northern direction in temples or in water bodies.[87] The Vishnudharmottara Purana prescribes worship for Matsya for grain.[88] Matsya is invoked as a form of Vishnu in hymns in the Brahma Purana.[89] The Vishnu Sahasranama version of the Garuda Purana includes Matsya.[90] The Vishnu Sahasranama in the Skanda Purana includes Matsya, Maha-matsya ("Great fish") and Timingila ("a great aquatic creature").[91]

The third day in the bright fortnight of the Hindu month of Chaitra is celebrated as Matsya Jayanti, the birthday of Matsya, when his worship is recommended.[65] Vishnu devotees observe a fast from a day before the holy day; take a holy bath on Matsya Jayanti and worship Matsya or Vishnu in the evening, ending their fast. Vishnu temples organize a special Puja.[92] The Meena community claim a mythological descent from Matsya, who is called Meenesh ("Lord of the Meenas"/ "Fish-Lord").[93] Matsya Jayanti is celebrated as Meenesh Jayanti by the Meenas.[94][95]

The Varaha Purana and the Margashirsha-Mahatmya of the Padma Purana recommends a vrata (vow) with fasting and worshipping Matsya (as a golden fish) in a three lunar-day festival culminating on the twelfth lunar day of the month of Margashirsha.[96][97]

There are very few temples dedicated to Matsya. Prominent ones include the Shankhodara temple in Bet Dwarka and Vedanarayana Temple in Nagalapuram.[85] Matsya Narayana Temple, Bangalore also exists. The Brahma Purana describes that Matsya-madhava (Vishnu as Matsya) is worshipped with Shveta-madhava (King Shveta) in the Shveta-madhava temple of Vishnu near the sacred Shweta ganga pond in Puri.[57][98][58] A temple to Machhenarayan (Matsya) is found in Machhegaun, Nepal, where an annual fair is held in honour of the deity.[99] The Koneswaram Matsyakeswaram temple in Trincomalee, Sri Lanka is now destroyed.

There are three temples dedicated to Matsya in Kerala. The Sree Malsyavathara Mahavishnu Temple is located in the small town of Meenangadi situated on the highway between Kalpetta and Sulthan Bathery in Wayanad. Matsyamurti is the name of the principal deity, though the idol itself is that of Vishnu. The second temple dedicated to Matsya in the state is the Mootoli Sree Mahavishnu Temple in Kakkodi, Kozhikode. The third temple is the Perumeenpuram Vishnu Temple in Kakkur, Kozhikode. The idol is that of Matsya. The main ceremony of this temple for devotees is called mīnūt (feeding the fish).

Notes

- ^ Manu is presented as the ancestor of two mythical royal dynasties (solar or son-based, lunar or daughter-based)[30][31]

- ^ As per Hindu time cycles, a kalpa is a period of 4.32 billion years, equivalent to a day in the life of Brahma. Each kalpa is divided into 14 manvantaras, each reigned by a Manu, who becomes progenitor of mankind. Brahma creates the worlds and life in his day - the kalpa and sleeps in his night - the pralaya, when Brahma's creation is destroyed. Brahma reawakens at the start of the new kalpa (day) and recreates.

References

- ^ Jośī, Kanhaiyālāla (2007). Matsya mahāpurāṇa: An exhaustive introduction, Sanskrit text, English translation, scholarly notes and index of verses. Parimal Publications. ISBN 9788171103058. Archived from the original on 8 April 2023. Retrieved 10 July 2022.

- ^ Bandyopadhyaya, Jayantanuja (2007). Class and Religion in Ancient India. Anthem Press. p. 136. ISBN 978-1-84331-332-8. Archived from the original on 8 October 2022. Retrieved 10 July 2022.

- ^ Valborg, Helen (2007). Symbols of the Eternal Doctrine: From Shamballa to Paradise. Theosophy Trust Books. p. 313. ISBN 978-0-9793205-1-4. Archived from the original on 8 October 2022. Retrieved 10 July 2022.

- ^ Dalal, Roshen (18 April 2014). Hinduism: An Alphabetical Guide. Penguin UK. ISBN 978-81-8475-277-9. Archived from the original on 8 October 2022. Retrieved 10 July 2022.

- ^ Ninan, M. M. (23 June 2008). The Development of Hinduism. Madathil Mammen Ninan. p. 234. ISBN 978-1-4382-2820-4. Archived from the original on 8 October 2022. Retrieved 10 July 2022.

- ^ Mayrhofer, Manfred (1996). Entry “mátsya-”. In: Etymologisches Wörterbuch des Altindoarischen [Etymological Dictionary of Old Indo-Aryan] Volume II. Heidelberg: Carl Winter Universitätsverlag, 1996. pp. 297-298. (In German)

- ^ "matsya/matsa". Monier-Williams Sanskrit-English Dictionary. 1899. p. 776. Archived from the original on 16 September 2021. Retrieved 26 September 2020.

- ^ Franco, Rendich (14 December 2013). Comparative etymological Dictionary of classical Indo-European languages: Indo-European - Sanskrit - Greek - Latin. Rendich Franco. pp. 383, 555–556.

- ^ "mad". Monier-Williams Sanskrit-English Dictionary. 1899. p. 777. Archived from the original on 8 October 2022. Retrieved 26 September 2020.

- ^ Yaska; Sarup, Lakshman (1967). The Nighantu and the Nirukta. Robarts - University of Toronto. Delhi Motilal Banarsidass. p. 108 (English section).

- ^ "maccha". Monier-Williams Sanskrit-English Dictionary. 1899. p. 773. Archived from the original on 16 September 2021. Retrieved 26 September 2020.

- ^ A. L. Dallapiccola (2003). Hindu Myths. University of Texas Press. pp. 19–20. ISBN 978-0-292-70233-2.

- ^ a b Roy 2002, p. 79.

- ^ a b c d Krishna 2009, p. 33.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Bonnefoy 1993, pp. 79–80.

- ^ a b Alain Daniélou (1964). The Myths and Gods of India: The Classic Work on Hindu Polytheism from the Princeton Bollingen Series. Inner Traditions. pp. 166–167 with footnote 1. ISBN 978-0-89281-354-4.

- ^ Aiyangar 1901, pp. 120–1.

- ^ "Satapatha Brahmana Part 1 (SBE12): First Kânda: I, 8, 1. Eighth Adhyâya. First Brâhmana". www.sacred-texts.com. Archived from the original on 10 April 2021. Retrieved 28 December 2019.

- ^ Dikshitar 1935, pp. 1–2.

- ^ Roy 2002, p. 81.

- ^ a b Dhavamony, Mariasusai (1982). Classical Hinduism. Gregorian Biblical BookShop. pp. 112–113. ISBN 978-88-7652-482-0.

- ^ Aiyangar 1901, pp. 121–2.

- ^ Bloomfield, Maurice (1973) [1897]. Hymns Of The Atharva-veda. UNESCO Collection of Representative Works - Indian Series. Motilal Banarsidas. pp. 5–6, 679.

- ^ Unknown (1860–1870), Vishnu as Matsya, archived from the original on 11 June 2023, retrieved 11 June 2023

- ^ Rao 1914, p. 124.

- ^ "The Mahabharata, Book 3: Vana Parva: Markandeya-Samasya Parva: Section CLXXXVI". www.sacred-texts.com. Archived from the original on 20 October 2019. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- ^ Roy 2002, pp. 84–5.

- ^ Alf Hiltebeitel (1991). The cult of Draupadī: Mythologies. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 177–178, 202–203 with footnotes. ISBN 978-81-208-1000-6.

- ^ a b c d Bonnefoy 1993, p. 80.

- ^ Ronald Inden; Jonathan Walters; Daud Ali (2000). Querying the Medieval: Texts and the History of Practices in South Asia. Oxford University Press. pp. 180–181. ISBN 978-0-19-535243-6.

- ^ Bibek Debroy; Dipavali Debroy (2005). The history of Puranas. Bharatiya Kala. p. 640. ISBN 978-81-8090-062-4.

- ^ Shastri & Tagare 1999, p. 1116.

- ^ Matsya mahāpurāṇa : an exhaustive introduction, Sanskrit text, English translation, scholarly notes and index of verses. Kanhaiyālāla Jośī (1st ed.). Delhi: Parimal Publications. 2007. ISBN 978-81-7110-306-5. OCLC 144550129.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b c d e f Roshen Dalal (2011). Hinduism: An Alphabetical Guide. Penguin Books India. p. 250. ISBN 978-0-14-341421-6. Retrieved 12 January 2013.

- ^ Ariel Glucklich (2008). The Strides of Vishnu: Hindu Culture in Historical Perspective. Oxford University Press. pp. 155–165. ISBN 978-0-19-971825-2.

- ^ a b Roy 2002, p. 85.

- ^ a b Garuda Purana 2002, p. 4.

- ^ Shastri 1990, p. 514.

- ^ Shastri & Tagare 1999, pp. 1116, 1118.

- ^ Shastri & Tagare 1999, p. 1123.

- ^ Rao pp. 124-125

- ^ George M. Williams 2008, p. 213.

- ^ Shastri & Tagare 1999, pp. 1116–24.

- ^ Shastri, Bhatt & Gangadharan 1998, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Rao pp. 125-6

- ^ Shastri, Bhatt & Gangadharan 1998, p. 734.

- ^ Varaha Purana 1960, pp. 33–5.

- ^ Varaha Purana 1960, p. 1.

- ^ Varaha Purana 1960, pp. 59, 259.

- ^ Garuda Purana 2002, p. 411.

- ^ Garuda Purana 2002, p. 268.

- ^ Narada Purana 1952, pp. 1978–9.

- ^ a b Shastri 2000, p. 873.

- ^ Padma Purana 1954, pp. 2656–7.

- ^ Skanda Purana 1998a, pp. 125–7.

- ^ Padma Purana 1956, pp. 3174–6.

- ^ a b Shah 1990, p. 328.

- ^ a b Narada Purana 1952, p. 1890.

- ^ Nagar 2005, pp. 74, 194, volume II.

- ^ Skanda Purana 1998, p. 227.

- ^ Shastri & Tagare 1999, p. 26.

- ^ Garuda Purana 2002, p. 265.

- ^ Garuda Purana 2002a, p. 869.

- ^ Shastri 1990, p. 774.

- ^ a b Narada Purana 1997, p. 1450.

- ^ Varaha Purana 1960, p. 13.

- ^ Padma Purana 1956, p. 3166.

- ^ Skanda Purana 2003, pp. 431–2.

- ^ Shastri & Tagare 1999, pp. 26, 190.

- ^ N.A (1951). THE SKANDA-PURANA PART. 7. MOTILAL BANARSIDASS PUBLISHERS PVT. LTD, DELHI. p. 286.

- ^ Wilson 1862, pp. 57–8.

- ^ Shastri, Bhatt & Gangadharan 1998, p. 326.

- ^ Wilson 1862a, pp. 125–6.

- ^ Brahma Purana 1955, p. 104.

- ^ Shastri, Bhatt & Gangadharan 1998, p. 129.

- ^ Shah 1990, p. 240.

- ^ Rao 1914, p. 127.

- ^ a b British Museum; Anna Libera Dallapiccola (2010). South Indian Paintings: A Catalogue of the British Museum Collection. Mapin Publishing Pvt Ltd. pp. 78, 117, 125. ISBN 978-0-7141-2424-7. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- ^ "Ancient India". www.art-and-archaeology.com. Archived from the original on 23 January 2012. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- ^ Krishna 2009, p. 35.

- ^ Roy 2002, pp. 79–80.

- ^ Roy 2002, pp. 80–2.

- ^ Roy 2002, p. 82.

- ^ Roy 2002, pp. 83–4.

- ^ a b Krishna p. 36

- ^ Shastri & Tagare 1999, p. 820.

- ^ Shastri, Bhatt & Gangadharan 1998, pp. 116, 172.

- ^ Shah 1990, p. 118.

- ^ Brahma Purana 1955, pp. 336, 395, 447, 763, 970.

- ^ Garuda Purana 2002, p. 59.

- ^ Skanda Purana 2003a, p. 253.

- ^ "Matsya Jayanti 2021: Date, time, significance, puja, fast". India Today. 15 April 2021. Archived from the original on 5 June 2021. Retrieved 5 June 2021.

- ^ Kapur, Nandini Sinha (2000). "Reconstructing Identities and Situating Themselves in History : A Preliminary Note on the Meenas of Jaipur Locality". Indian Historical Review. 27 (1): 29–43. doi:10.1177/037698360002700103. S2CID 141602938.

the entire community claims descent from the Matsya (fish) incarnation of Vishnu

- ^ "मीनेष जयंती:मीणा समाज ने मनाई भगवान मीनेष जयंती". Dainik Bhaskar. 15 April 2021. Archived from the original on 5 June 2021. Retrieved 5 June 2021.

- ^ "मिनेष जयंती पर मीणा समाज ने निकाली भव्य शोभायात्रा". Patrika News (in Hindi). 8 April 2019. Archived from the original on 5 June 2021. Retrieved 5 June 2021.

- ^ Varaha Purana 1960, pp. 118–23.

- ^ Skanda Purana 1998a, pp. 253–6.

- ^ Starza, O. M. (1993). The Jagannatha Temple at Puri: Its Architecture, Art, and Cult. BRILL. p. 11. ISBN 978-90-04-09673-8.

- ^ "Machhenarayan fair put off this year due to COVID-19". GorakhaPatra. 11 September 2020. Archived from the original on 17 September 2021. Retrieved 26 September 2020.

Further reading

- Aiyangar, Narayan (1901). Essays On Indo Aryan Mythology. Madras: Addison and Company.

- Bonnefoy, Yves (1993). Asian Mythologies. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-06456-7.

- Dikshitar, V. R. Ramachandra (1935). Matsya Purana a study.

- Roy, J. (2002). Theory of Avatāra and Divinity of Chaitanya. Atlantic. ISBN 978-81-269-0169-2.

- Krishna, Nanditha (2009). The Book of Vishnu. Penguin Books India. ISBN 978-0-14-306762-7.

- Rao, T.A. Gopinatha (1914). Elements of Hindu iconography. Vol. 1: Part I. Madras: Law Printing House.

- George M. Williams (2008). Handbook of Hindu Mythology. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-533261-2.

- Mani, Vettam (1975). Puranic Encyclopaedia: a Comprehensive Dictionary with Special Reference to the Epic and Puranic Literature. Motilal Banarsidass Publishers. ISBN 978-0-8426-0822-0.

- Shah, Priyabala (1990). Shri Vishnudharmottara. The New Order Book Co.

- H H Wilson (1911). Puranas. p. 84.

- Shastri, J. L.; Tagare, G. V. (1999) [1950]. The Bhāgavata Purāṇa. Motilal Banarsidas.

- Shastri, J. L.; Bhatt, G. P.; Gangadharan, N. (1998) [1954]. Agni Purana. Motilal Banarsidass Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

- Wilson, H. H. (Horace Hayman) (1862). The Vishnu Purána : a system of Hindu mythology and tradition. Works by the late Horace Hayman Wilson. Vol. VI. Princeton Theological Seminary Library. London : Trübner.

- Wilson, H. H. (Horace Hayman) (1862a). The Vishnu Purána : a system of Hindu mythology and tradition. Works by the late Horace Hayman Wilson. Vol. VII. Princeton Theological Seminary Library. London : Trübner.

- Brahma Purana. UNESCO collection of Representative Works - Indian Series. Motilal Banarsidass. 1955.

- Nagar, Shanti Lal (2005). Brahmavaivarta Purana. Parimal Publications.

- The Garuda Purana. Vol. 1. Motilal Banarsidas. 2002 [1957].

- The Garuda Purana. Vol. 3. Motilal Banarsidas. 2002 [1957].

- Shastri, J.L. (1990) [1951]. Linga Purana. Vol. 2. Motilal Banarsidass Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

- The Narada Purana. Vol. 4. Motilal Banarsidas. 1997 [1952].

- The Narada Purana. Vol. 5. Motilal Banarsidas. 1952.

- The Varaha Purana. UNESCO collection of Representative Works - Indian Series. Vol. 1. Motilal Banarsidas. 1960.

- Shastri, J. L. (2000) [1950]. The Śiva Purāṇa. Vol. 2. Motilal Banarsidas.

- Padma Purana. Vol. 8. Motilal Banarsidas. 1956.

- Padma Purana. Vol. 9. Motilal Banarsidas. 1956.

- The Skanda Purana. Vol. 5. Motilal Banarsidas. 1998 [1951].

- The Skanda Purana. Vol. 6. Motilal Banarsidas. 1998 [1951].

- The Skanda Purana. Vol. 15. Motilal Banarsidas. 2003 [1957].

- The Skanda Purana. Vol. 12. Motilal Banarsidas. 2003 [1955].

External links

Media related to Matsya at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Matsya at Wikimedia Commons