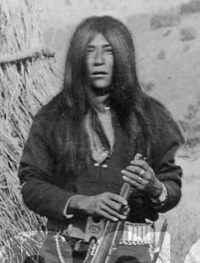

Massai

Massai | |

|---|---|

Massai in Geronimo's Camp, March 1886 | |

| Born | c. 1847 near Globe, Arizona, U.S. |

| Died | 1911 near Socorro, New Mexico, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Gunshot wounds |

'Massai (also known as: Masai, Massey, Massi, Mah–sii, Massa, Wasse, Wassil, Wild, Sand Coyote or by the nickname "Big Foot" Massai was a member of the Mimbres/Mimbreños local group of the Chihenne band of the Chiricahua Apache. He was a warrior who was captured but escaped from a train that was sending the scouts and renegades to Florida to be held with Geronimo and Chihuahua.

It is possible that Massai's true Apache name was Nogusea (meaning "crazy", according to Jason Betzinez and James Kaywaykla); he was enlisted as a member of Chatto's band as known as Ma-Che.[1]

Life

Born to White Cloud and Little Star at Mescal Mountain, Arizona, near Globe.[2][3] He later married a local Chiricahua and they had two children.[4]

Massai later met Geronimo, who was recruiting Apache to fight American settlers and soldiers. Massai and a Tonkawa named Gray Lizard agreed to join Geronimo, who instructed them to lay in supplies of arms, food, and ammunition.[5] Other sources state that Massai also served the United States government on two occasions, once in 1880 and the other in 1885, as an Apache Scout.[6] Upon traveling to meet Geronimo's forces, the two were informed that Geronimo had been arrested.[5] Both men were arrested by Chiricahua Apache Scouts and disarmed. Massai was placed onto a prison train as a prisoner of war along with Gray Lizard, who voluntarily agreed[7] to accompany Massai, together with the remaining Chiricahua Apache who had either been captured or had surrendered to the army. This included the Apache Scouts, who were now deemed expendable and undesirable.[5]

Massai and Gray Lizard later escaped from the prison train near Saint Louis, Missouri.[5] The two men walked some 1,200 miles back to the Mescalero Apache tribal area, crossing the Pecos River, and Capitan Gap. Near Sierra Blanca, New Mexico, the two men encountered a group of Mescalero Apache. Several days later, the two parted at Three Rivers, never to see each other again. Gray Lizard departed for Mescal Mountain and the San Carlos Indian Reservation near present-day Globe, Arizona, while Massai stayed on the run, raiding along what is today the New Mexico-Arizona border, and periodically taking refuge across the border in Mexico. His name appeared in San Carlos Agency reports from 1887 to 1890.[8] He later kidnapped and married (c. 1887) a Mescalero Apache girl named Zan-a-go-li-che and took her home to his family at Mescal Mountain. Massai and Zanagoliche had six children together.[9]

Demise

Massai's later life and death are the subject of some dispute. According to Alberta Begay, his daughter, in 1911, Massai had been forced to kill a white man during a confrontation when the man's horse fled. While attempting to recover the horse, he encountered a posse and was shot. Before this event, Massai had instructed his wife, Zanagoliche, to take their children to a Mexican friend's house for a couple of days and then travel north by night to the Mescalero Apache Reservation. He also spoke to his eldest son, advising him to protect the family and follow specific instructions if Massai did not return. After Massai was shot, his eldest son returned to report that he did not know if Massai was still alive. Zanagoliche waited until the following morning, at which point she and her son went to the site of the encounter. There, they found a burned camp and human bones, alongside a belt buckle, which she recognized as her husband's. Zanagoliche buried the bones and, following her husband’s earlier instructions, took the children to the Mescalero Reservation.[10]

Another account states that Massai escaped over the border to Mexico, eventually settling in the Sierra Madre mountains with a group of rebellious Chiricahuas who had refused to surrender with Geronimo.

In popular culture

Massai was portrayed (in brownface) by Burt Lancaster in the 1954 film Apache.

See also

- Apache Campaign (1896)

- Kelvin Grade Massacre

- List of fugitives from justice who disappeared

- Renegade period of the Apache Wars

References

- ^ Alicia Delgadillo, Miriam Perrett, From Fort Marion to Fort Sill: A Documentary History of the Chiricahua Apache Prisoners of War, 1886–1913, University of Nebraska Press, ISBN 978-0803243798, 2013, pp. 178–179

- ^ Ball, Eve, Indeh, An Apache Odyssey, Norman OK: University of Oklahoma Press, ISBN 978-0-8061-2165-9 (1988), pp. 248–261

- ^ Begay, Alberta, Eve Ball, and Sherry Robinson, Apache Voices: Their Stories of Survival as Told to Eve Ball, Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press, ISBN 978-0826321633(2003), pp. 87–102

- ^ Begay, pp. 248–261

- ^ a b c d Ball, pp. 249–252

- ^ Begay, pp. 89–90

- ^ Begay, p. 90: As a Tonkawa, Gray Lizard was not compelled to join the Chiricahuan prisoners being deported.

- ^ Begay, p. 94

- ^ Begay, pp. 96–97

- ^ Massai, the last fighting Apache, was a living legend in the Old West