Mantra

A mantra (Pali: mantra) or mantram (Devanagari: मन्त्रम्)[1] is a sacred utterance, a numinous sound, a syllable, word or phonemes, or group of words (most often in an Indo-Iranian language like Sanskrit or Avestan) believed by practitioners to have religious, magical or spiritual powers.[2][3] Some mantras have a syntactic structure and a literal meaning, while others do not.[2][4]

ꣽ, ॐ (Aum, Om) serves as an important mantra in various Indian religions. Specifically, it is an example of a seed syllable mantra (bijamantra). It is believed to be the first sound in Hinduism and as the sonic essence of the absolute divine reality. Longer mantras are phrases with several syllables, names and words. These phrases may have spiritual interpretations such as a name of a deity, a longing for truth, reality, light, immortality, peace, love, knowledge, and action.[2][5] Examples of longer mantras include the Gayatri Mantra, the Hare Krishna mantra, Om Namah Shivaya, the Mani mantra, the Mantra of Light, the Namokar Mantra, and the Mūl Mantar. Mantras without any actual linguistic meaning are still considered to be musically uplifting and spiritually meaningful.[6]

The use, structure, function, importance, and types of mantras vary according to the school and philosophy of Jainism, Buddhism, Hinduism, Zoroastrianism, and Sikhism.[3][7] A common practice is japa, the meditative repetition of a mantra, usually with the aid of a mala (prayer beads). Mantras serve a central role in the Indian tantric traditions, which developed elaborate yogic methods which make use of mantras.[6][8] In tantric religions (often called "mantra paths", Sanskrit: Mantranāya or Mantramarga), mantric methods are considered to be the most effective path. Ritual initiation (abhiseka) into a specific mantra and its associated deity is often a requirement for reciting certain mantras in these traditions. However, in some religious traditions, initiation is not always required for certain mantras, which are open to all.[9][5]

The word mantra is also used in English to refer to something that is said frequently and is deliberately repeated over and over.

Etymology and origins

The earliest mention of mantras is found in the Vedas of ancient India and the Avesta of ancient Iran.[10] Both Sanskrit mántra and the equivalent Avestan mąθra go back to the common Proto-Indo-Iranian *mantram, consisting of the Indo-European *men "to think" and the instrumental suffix *trom.[11][12][13][14][15] Due to the linguistic and functional similarities, they must go back to the common Indo-Iranian period, commonly dated to around 2000 BCE.[16][17]

Scholars[2][6] consider the use of mantras to have begun in India before 1000 BC. By the middle Vedic period (1000 BC to 500 BC) – claims Frits Staal – mantras in Hinduism had developed into a blend of art and science.[6]

The Chinese translation is 真言; zhenyan; 'true words', the Japanese on'yomi reading of the Chinese being shingon (which is also used as the proper name for the Shingon sect). According to Alex Wayman and Ryujun Tajima, "Zhenyan" (or "Shingon") means "true speech", has the sense of "an exact mantra which reveals the truth of the dharmas", and is the path of mantras.[18][19]

According to Bernfried Schlerath, the concept of sātyas mantras is found in Indo-Iranian Yasna 31.6 and the Rigveda, where it is considered structured thought in conformity with the reality or poetic (religious) formulas associated with inherent fulfillment.[20]

Definition

There is no generally accepted definition of mantra.[21] As a result, there is a long history of scholarly disagreement on the meaning of mantras and whether they are instruments of mind, as implied by the etymological origin of the word mantra. One school suggests mantras are mostly meaningless sound constructs, while the other holds them to be mostly meaningful linguistic instruments of mind.[5] Both schools agree that mantras have melody and a well designed mathematical precision in their construction and that their influence on the reciter and listener is similar to that is observed in people around the world listening to their beloved music that is devoid of words.[2][6]

In Oxford Living Dictionary mantra is defined as a word or sound repeated to aid concentration in meditation.[22] Cambridge Dictionary provides two different definitions.[23] The first refers to Hinduism and Buddhism: a word or sound that is believed to have a special spiritual power. The second definition is more general: a word or phrase that is often repeated and expresses a particularly strong belief. For instance, a football team can choose individual words as their own "mantra."[citation needed]

Louis Renou has defined mantra as a thought.[24] Mantras are structured formulae of thoughts, claims Silburn.[25] Farquhar concludes that mantras are a religious thought, prayer, sacred utterance, but also believed to be a spell or weapon of supernatural power.[26] Zimmer defines mantra as a verbal instrument to produce something in one's mind.[27] Agehananda Bharati defines mantra, in the context of the Tantric school of Hinduism, to be a combination of mixed genuine and quasi-morphemes arranged in conventional patterns, based on codified esoteric traditions, passed on from a guru to a disciple through prescribed initiation.[28]

Jan Gonda, a widely cited scholar on Indian mantras,[29] defines mantra as general name for the verses, formulas or sequence of words in prose which contain praise, are believed to have religious, magical or spiritual efficiency, which are meditated upon, recited, muttered or sung in a ritual, and which are collected in the methodically arranged ancient texts of Hinduism.[30] By comparing the Old Indic Vedic and Old Iranian Avestan traditions, Gonda concludes that in the oldest texts, mantras were "means of creating, conveying, concentrating and realizing intentional and efficient thought, and of coming into touch or identifying oneself with the essence of the divinity".[2] In some later schools of Hinduism, Gonda suggests a mantra is sakti (power) to the devotee in the form of formulated and expressed thought.[2]

Frits Staal, a specialist in the study of Vedic ritual and mantras, clarifies that mantras are not rituals, they are what is recited or chanted during a ritual.[6] Staal[6] presents a non-linguistic view of mantras. He suggests that verse mantras are metered and harmonized to mathematical precision (for example, in the viharanam technique), which resonate, but a lot of them are a hodgepodge of meaningless constructs such as are found in folk music around the world. Staal cautions that there are many mantras that can be translated and do have spiritual meaning and philosophical themes central to Hinduism, but that does not mean all mantras have a literal meaning. He further notes that even when mantras do not have a literal meaning, they do set a tone and ambiance in the ritual as they are recited, and thus have a straightforward and uncontroversial ritualistic meaning.[6] The sounds may lack literal meaning, but they can have an effect. He compares mantras to bird songs, that have the power to communicate, yet do not have a literal meaning.[32] On that saman category of Hindu mantras, which Staal described as resembling the arias of Bach's oratorios and other European classics, he notes that these mantras have musical structure, but they almost always are completely different from anything in the syntax of natural languages. Mantras are literally meaningless, yet musically meaningful to Staal.[33] The saman chant mantras were transmitted from one Hindu generation to next verbally for over 1000 years but never written, a feat, suggests Staal, that was made possible by the strict mathematical principles used in constructing the mantras. These saman chant mantras are also mostly meaningless, cannot be literally translated as Sanskrit or any Indian language, but nevertheless are beautiful in their resonant themes, variations, inversions, and distribution.[6] They draw the devotee in. Staal is not the first person to view Hindu mantras in this manner. The ancient Hindu Vedic ritualist Kautsa was one of the earliest scholars to note that mantras are meaningless; their function is phonetic and syntactic, not semantic.[34]

Harvey Alper[35] and others[36] present mantras from the linguistic point view. They admit Staal's observation that many mantras do contain bits and pieces of meaningless jargon, but they question what language or text doesn't. The presence of an abracadabra bit does not necessarily imply the entire work is meaningless. Alper lists numerous mantras that have philosophical themes, moral principles, a call to virtuous life, and even mundane petitions. He suggests that from a set of millions of mantras, the devotee chooses some mantras voluntarily, thus expressing that speaker's intention, and the audience for that mantra is that speaker's chosen spiritual entity. Mantras deploy the language of spiritual expression, they are religious instruments, and that is what matters to the devotee. A mantra creates a feeling in the practicing person. It has an emotive numinous effect, it mesmerizes, it defies expression, and it creates sensations that are by definition private and at the heart of all religions and spiritual phenomena.[2][28][37]

Hinduism

| Part of a series on |

| Hinduism |

|---|

|

History

During the early Vedic period, Vedic poets became fascinated by the inspirational power of poems, metered verses, and music. They referred to them with the root dhi-, which evolved into the dhyana (meditation) of Hinduism, and the language used to start and assist this process manifested as a mantra.[6] By the middle vedic period (1000 BC to 500 BC), mantras were derived from all vedic compositions. They included ṛc (verses from Rigveda for example), sāman (musical chants from the Sāmaveda for example), yajus (a muttered formula from the yajurveda for example), and nigada (a loudly spoken yajus). During the Hindu Epics period and after, mantras multiplied in many ways and diversified to meet the needs and passions of various schools of Hinduism.[38] In the Linga Purana, Mantra is listed as one of the 1,008 names of Lord Shiva.[39]

Numerous ancient mantras are found in the Saṃhitā portion of the Vedas. The Saṃhitās are the most ancient layer of the Vedas, and contain numerous mantras, hymns, prayers, and litanies.[40] The Rigveda Samhita contains about 10552 Mantras, classified into ten books called Mandalas. A Sukta is a group of Mantras.[41] Mantras come in many forms, including ṛc (verses from the Rigveda for example) and sāman (musical chants from the Sāmaveda for example).[2][6]

In Hindu tradition, Vedas are sacred scriptures which were revealed (and not composed) by the seers (Rishis). According to the ancient commentator and linguist, Yaska, these ancient sacred revelations were then passed down through an oral tradition and are considered to be the foundation for the Hindu tradition.[41]

Mantras took a center stage in Tantric traditions,[38] which made extensive ritual and meditative use of mantras, and posited that each mantra is a deity in sonic form.[8]

Function and structure

One function of mantras is to solemnize and ratify rituals.[42] Each mantra, in Vedic rituals, is coupled with an act. According to Apastamba Srauta Sutra, each ritual act is accompanied by one mantra, unless the Sutra explicitly marks that one act corresponds to several mantras. According to Gonda,[43] and others,[44] there is a connection and rationale between a Vedic mantra and each Vedic ritual act that accompanies it. In these cases, the function of mantras was to be an instrument of ritual efficacy for the priest, and a tool of instruction for a ritual act for others.

Over time, as the Puranas and Epics were composed, the concepts of worship, virtues and spirituality evolved in Hinduism and new schools of Hinduism were founded, each continuing to develop and refine its own mantras. In Hinduism, suggests Alper,[45] the function of mantras shifted from the quotidian to redemptive. In other words,[46] in Vedic times, mantras were recited a practical, quotidian goal as intention, such as requesting a deity's help in the discovery of lost cattle, cure of illness, succeeding in competitive sport or journey away from home. The literal translation of Vedic mantras suggests that the function of mantra, in these cases, was to cope with the uncertainties and dilemmas of daily life. In a later period of Hinduism,[47] mantras were recited with a transcendental redemptive goal as intention, such as escape from the cycle of life and rebirth, forgiveness for bad karma, and experiencing a spiritual connection with the god. The function of mantras, in these cases, was to cope with the human condition as a whole. According to Alper,[5] redemptive spiritual mantras opened the door for mantras where every part need not have a literal meaning, but together their resonance and musical quality assisted the transcendental spiritual process. Overall, explains Alper, using Śivasūtra mantras as an example, Hindu mantras have philosophical themes and are metaphorical with social dimension and meaning; in other words, they are a spiritual language and instrument of thought.[47]

According to Staal,[6] Hindu mantras may be spoken aloud, anirukta (not enunciated), upamsu (inaudible), or manasa (not spoken, but recited in the mind). In ritual use, mantras are often silent instruments of meditation.

Invocation

For almost every mantra, there are six limbs called Shadanga.[48] These six limbs are: Seer (Rishi), Deity (Devata), Seed (Beeja), Energy (Shakti), Poetic Meter (chanda), and Lock (Kilaka).

Methods

The most basic mantra is Om, which in Hinduism is known as the "pranava mantra," the source of all mantras. The Hindu philosophy behind this is the premise that before existence and beyond existence is only One reality, Brahman, and the first manifestation of Brahman expressed as Om. For this reason, Om is considered as a foundational idea and reminder, and thus is prefixed and suffixed to all Hindu prayers. While some mantras may invoke individual gods or principles, fundamental mantras such as Shanti Mantra, the Gayatri Mantra and others ultimately focus on the One reality.

Japa

Mantra japa is a practice of repetitively uttering the same mantra[49] for an auspicious number of times, the most popular being 108, and sometimes just 5, 10, 28 or 1008.[2][50] Japa is found in personal prayer or meditative efforts of some Hindus, as well during formal puja (group prayers). Japa is assisted by malas (bead necklaces) containing 108 beads and a head bead (sometimes referred to as the 'meru', or 'guru' bead); the devotee using their fingers to count each bead as they repeat the chosen mantra. Having reached 108 repetitions, if they wish to continue another cycle of mantras, the devotee turns the mala around without crossing the head bead and repeats the cycle.[51] Japa-yajna is claimed to be most effective if the mantra is repeated silently in mind (manasah).[50]

According to this school, any shloka from holy Hindu texts like the Vedas, Upanishads, Bhagavad Gita, Yoga Sutra, even the Mahabharata, Ramayana, Durga saptashati or Chandi is a mantra, thus can be part of the japa, repeated to achieve a numinous effect.[52][53][54] The Dharmasāstra claims Gāyatri mantra derived from Rig Veda verse 3.62.10, and the Purușasūkta mantra from Rig Veda verse 10.90 are most auspicious mantras for japa at sunrise and sunset; it is claimed to purify the mind and spirit.[2]

Kirtan (chanting)

Kirtan is a more musical form of mantric practice. It is a common method in the bhakti traditions, such as Gaudiya Vaishnavism.[55] Kirtan includes call and response forms of chanting accompanied by various Indian instruments (such as the tabla, mrdanga and harmonium), and it may also include dancing and theatrical performance.[56][57][58] Kirtan is also common in Sikhism.

Tantric

Tantric Hindu traditions see the universe as sound.[59] The supreme (para) brings forth existence through the Word (shabda). Creation consists of vibrations at various frequencies and amplitudes giving rise to the phenomena of the world.

Buhnemann notes that deity mantras are an essential part of Tantric compendia. The tantric mantras vary in their structure and length. Mala mantras are those mantras which have an enormous number of syllables. In contrast, bija mantras are one-syllabled, typically ending in anusvara (a simple nasal sound). These are derived from the name of a deity; for example, Durga yields dum and Ganesha yields gam. Bija mantras are prefixed and appended to other mantras, thereby creating complex mantras. In the tantric school, these mantras are believed to have supernatural powers, and they are transmitted by a preceptor to a disciple in an initiation ritual.[60] Tantric mantras found a significant audience and adaptations in medieval India, Southeast Asia and numerous other Asian countries with Buddhism.[61]

Majumdar and other scholars[2][62] suggest mantras are central to the Tantric school, with numerous functions. From initiating and emancipating a tantric devotee to worshiping manifested forms of the divine. From enabling heightened sexual energy in the male and the female to acquiring supernormal psychological and spiritual power. From preventing evil influences to exorcizing demons, and many others.[63] These claimed functions and other aspects of the tantric mantra are a subject of controversy among scholars.[64]

Tantra usage is not unique to Hinduism: it is also found in Buddhism both inside and outside India.[65]

Examples

Gayatri

- The Gayatri mantra is considered one of the most universal of all Hindu mantras, invoking the universal Brahman as the principle of knowledge and the illumination of the primordial Sun. The mantra is extracted from the 10th verse of Hymn 62 in Book III of the Rig Veda.[66]

- ॐ भूर्भुवस्व: |तत्सवितुर्वरेण्यम् |भर्गो देवस्य धीमहि |धियो यो न: प्रचोदयात्

- Oṁ bhūr bhuvaḥ svaḥ tat savitur vareṇyaṃ bhargo devasya dhīmahi dhiyo yo naḥ pracodayāt,[67]

- "Let us meditate on that excellent glory of the divine Light (Vivifier, Sun). May he stimulate our understandings (knowledge, intellectual illumination)."[66]

Pavamana

- असतो मा सद्गमय । तमसो मा ज्योतिर्गमय । मृत्योर्मामृतं गमय ॥ asato mā sad-gamaya, tamaso mā jyotir-gamaya, mṛtyor-māmṛtaṃ gamaya.

- (Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad 1.3.28)[68]

- "from the unreal lead me to the real, from the dark lead me to the light, from death lead me to immortality."

Shanti

- Oṁ Sahanā vavatu sahanau bhunaktu sahavīryam karavāvahai tejasvi nāvadhītamastu

- Mā vidviṣāvahai

- Oṁ Shāntiḥ, Shāntiḥ, Shāntiḥ.

- "Om! Let the Studies that we together undertake be effulgent;

- Let there be no Animosity amongst us;

- Om! Peace, Peace, Peace."

- – Taittiriya Upanishad 2.2.2

Other

Other important Hindu mantras include:

- Mahāmṛtyuṃjaya-mantra (Great Death Defeating Mantra) - A popular Rigvedic mantra dedicated to Rudra

- Om̐ Namah Shivaya - one of the main mantras in Shaivism

- Om̐ kālabhairavāya namaḥ - a key mantra of Bhairava, the fierce form of Shiva

- Om̐ Namo Narayanaya - the principal mantra of Vishnu in Vaishnavism[69]

- Hare Krishna Maha Mantra - the most important mantra in the Vaishnava Bhakti tradition of Chaitanya Mahaprabhu

- Om̐ aim mahāsarasvatyai namaḥ - a mantra of Saraswati

- Om̐ Śrīm̐ Mahālakṣmyai Namaha - a Lakshmi mantra

- Om̐ Krim Kali - a Kali seed (bija) mantra

- Om̐ Śrī Durgāya Namaḥ - one of the principal mantras in Shaktism and Shaivism dedicated to Durga

- Ka E I La Hrim Ha Sa Ka La Ha Hrim Sa Ka La Hrim - the Panchadasi, the main mantra of Lalita in Srividya

- Om̐ Śrī Gaṇeśāya Namaḥ - a key mantra of Ganesha

- Om̐ Śrī Hanumate Namaḥ - the root mantra of Hanuman

- Om hrim ksaumugram viram mahavivnumjvalantam sarvatomukham Nrsimham bhisanam bhadrammrtyormrtyum namamyaham - Narasimha mahamantra

- Om̐ Namo Bhagavate Vāsudevāya - the key mantra in Bhagavatism

- Om̐ Aim Hreem Kleem Chamundayai Vichche - a mantra of the goddess Chamunda

- Om̐ Shree Ram Jai Ram Jai Jai Ram - a mantra of Rama

- Om̐ āim hrīm śrīm klīm - a mantra of the goddess in Shaktism

- The various mantras associated with the yogic Sūryanamaskāra (Sun Salutation) practice

- The various versions of the Gayatri

- So 'haṃ (I am He or I am That)

In the Shiva Sutras

Apart from Shiva Sutras, which originated from Shiva's tandava dance, the Shiva Sutras of Vasugupta[70] are a collection of seventy-seven aphorisms that form the foundation of the tradition of spiritual mysticism known as Kashmir Shaivism. They are attributed to the sage Vasugupta of the 9th century C.E. Sambhavopaya (1-1 to 1–22), Saktopaya (2-1 to 2–10) and Anavopaya (3-1 to 3–45) are the main sub-divisions, three means of achieving God consciousness, of which the main technique of Saktopaya is a mantra. But "mantra" in this context does not mean incantation or muttering of some sacred formula. The word "mantra" is used here in its etymological signification.[71] That which saves one by pondering over the light of Supreme I-consciousness is a mantra. The divine Supreme I-consciousness is the dynamo of all the mantras. Deha or body has been compared to wood, "mantra" has been compared to arani—a piece of wood used for kindling fire by friction; prana has been compared to fire. Sikha or flame has been compared to atma (Self); ambara or sky has been compared to Shiva. When prana is kindled by means of mantra used as arani, fire in the form of udana arises in susumna, and then just as flame arises out of kindled fire and gets dissolved in the sky, so also atma (Self) like a flame having burnt down the fuel of the body, gets absorbed in Shiva.[72]

Buddhism

In Early Buddhism

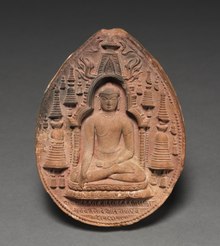

One of the most ancient Buddhist mantras is the famous Pratītyasamutpāda-gāthā, also known as the dependent origination dhāraṇī. This phrase is said to encapsulate the meaning of the Buddha's Teaching. It was a popular Buddhist verse and was used as a mantra.[73] This mantra is found inscribed on numerous ancient Buddhist statues, chaityas, and images.[74][75]

The Sanskrit version of this mantra is:

ye dharmā hetuprabhavā hetuṃ teṣāṃ tathāgato hyavadat, teṣāṃ ca yo nirodha evaṃvādī mahāśramaṇaḥ

The phrase can be translated as follows:

Of those phenomena which arise from causes: Those causes have been taught by the Tathāgata (Buddha), and their cessation too - thus proclaims the Great Ascetic.

Early Buddhist texts also contain various apotropaic chants which have similar functions to Vedic mantras. These are called parittas in Pali (Sanskrit: paritrana) and mean "protection, safeguard". They are still chanted in Theravada Buddhism to this day as a way to heal, protect from danger and bless.[76] Some of these are short Buddhist texts, like the Mangala Sutta, Ratana Sutta, and the Metta Sutta.

Theravada

According to the American Buddhist teacher Jack Kornfield:[77]

The use of mantra or the repetition of certain phrases in Pali is a highly common form of meditation in the Theravada tradition. Simple mantras use repetition of the Buddha's name, "Buddho", [as "Buddho" is actually a title rather than a name] or use the "Dhamma", or the "Sangha", the community, as mantra words. Other used mantras are directed toward developing loving kindness. Some mantras direct attention to the process of change by repeating the Pali phrase that means "everything changes", while other mantras are used to develop equanimity with phrases that would be translated, "let go".

"In contemporary Theravada practice, mantra practice is often combined with breathing meditation, so that one recites a mantra simultaneously with in-breath and out-breath to help develop tranquility and concentration. Mantra meditation is especially popular among lay people. Like other basic concentration exercises, it can be used simply to the mind, or it can be the basis for an insight practice where the mantra becomes the focus of observation of how life unfolds, or an aid in surrendering and letting go."[78]

The "Buddho" mantra is widespread in the Thai Forest Tradition and was taught by Ajahn Chah and his students.[79] Another popular mantra in Thai Buddhism is Samma-Araham, referring to the Buddha who has 'perfectly' (samma) attained 'perfection in the Buddhist sense' (araham), used in Dhammakaya meditation.[80][81]

In the Tantric Theravada tradition of Southeast Asia, mantras are central to their method of meditation. Popular mantras in this tradition include Namo Buddhaya ("Homage to the Buddha") and Araham ("Worthy One"). There are Thai Buddhist amulet katha: that is, mantras to be recited while holding an amulet.[82]

Mahayana Buddhism

The use of mantras became very popular with the rise of Mahayana Buddhism. Many Mahayana sutras contain mantras, bijamantras ("seed" mantras), dharanis and other similar phrases which were chanted or used in meditation.

According to Edward Conze, Buddhists initially used mantras as protective spells like the Ratana Sutta for apotropaic reasons. Even at this early stage, there was an idea that these spells were somehow connected with the Dharma in a deep sense. Conze argues that in Mahayana sutras like the White Lotus Sutra, and the Lankavatara Sutra, mantras become more important for spiritual reasons and their power increases. For Conze, the final phase of the development of Buddhist mantras is the tantric phase of Mantrayana. In this tantric phase, mantras are at the very center of the path to Buddhahood, acting as a part of the supreme method of meditation and spiritual practice.

One popular bija (seed) mantra in Mahayana Buddhism is the Sanskrit letter A (see A in Buddhism). This seed mantra was equated with Mahayana doctrines like Prajñaparamita (the Perfection of Wisdom), emptiness and non-arising.[83][84] This seed mantra remains in use in Shingon, Dzogchen and Rinzai Zen. Mahayana Buddhism also adopted the Om mantra, which is found incorporated into various Mahayana Buddhist mantras (like the popular Om Mani Padme Hum).

Another early and influential Mahayana "mantra" or dharani is the Arapacana alphabet (of non-Sanskrit origin, possibly Karosthi) which is used as a contemplative tool in the Long Prajñāpāramitā sutras.[85][86] The entire alphabet runs:[85]

a ra pa ca na la da ba ḍa ṣa va ta ya ṣṭa ka sa ma ga stha ja śva dha śa kha kṣa sta jña rta ha bha cha sma hva tsa bha ṭha ṇa pha ska ysa śca ṭa ḍha

In this practice, each letter stood for a specific idea (for example, "a" stands for non-arising (anutpada), and pa stands for "ultimate truth" (paramārtha).[85] As such, this practice was also a kind of mnemonic technique (dhāraṇīmukha) which allowed one to remember the key points of the teaching.[87]

The Mahayana sutras introduced various mantras into Mahayana Buddhism, such as:

- Mahayana sutras or texts often begin with the mantra: Om̐ namaḥ sarvajñāya (or just: namaḥ sarvajñāya, "Homage to omniscience") [88]

- Other Mahayana texts begin with Om̐ namo ratnatrayāya (Homage to the Three Jewels) [89]

- Shakyamuni Buddha's Mantra: Om̐ muni muni mahāmuni śākyamuni svāhā [90]

- Heart sutra (Prajñāpāramitāhṛdaya) mantra: Gate gate pāragate pārasaṃgate bodhi svāhā

- The mantra of bodhisattva Mañjuśrī: Om̐ arapacana dhīḥ

- Prajñaparamita-devi mantra from The Sutra of Mañjuśrī's Questions: Nama ārya prajñā pāramitāyāi svāhā [91]

- Kauśikaprajñāpāramitāsutra contains many Prajñaparamita mantras including: oṃ hrī śrī dhī śruti smṛti mati gati vijaye svāhā [92]

- A protective mantra found in the Sanskrit Lotus Sutra: agaṇe gaṇe gauri gandhāri caṇḍāli mātaṅgi pukkasi saṃkule vrūsali sisi svāhā [93]

- Medicine Guru mantra (in the Sutra of Medicine Guru): Om̐ bhaiṣajye bhaiṣajye mahābhaiṣajya-samudgate svāhā

- Avalokiteshvara's mantra (the Mani mantra): Om̐ maṇi padme hūṃ, first appearing in the Kāraṇḍavyūhasūtra (4th-5th century CE)

- Cundī dhāraṇī or mantra also first appeared in the Kāraṇḍavyūhasūtra: namaḥ saptānāṃ samyaksaṃbuddha koṭīnāṃ tadyathā oṃ cale cule cunde svāhā

- Amitabha Sukhavati Dhāraṇī, sometimes called the Pure Land Rebirth Mantra

- Mantra of Light of the Great Consecration (Ch: 大灌頂光真言): Om̐ Amogha Vairocana Mahāmudrā Maṇipadma Jvalapravartāya Hūṃ

East Asian Buddhism

In Chinese Buddhism, various mantras, including the Great Compassion Mantra, the Uṣṇīṣa Vijaya Dhāraṇī from the Uṣṇīṣa Vijaya Dhāraṇī Sutra, the Mahāmāyūrī Vidyārājñī Dhāraṇī, the Heart Sutra and various forms of Buddha remembrance are commonly chanted by both monastics and laymen. In China and Vietnam, a set of mantras known as the Ten Small Mantras (Chinese: 十小咒; Pinyin: Shíxiǎozhòu)[94] was established by the monk Yulin (Chinese: 玉琳國師; Pinyin: Yùlín Guóshī), a teacher of the Qing dynasty Shunzhi Emperor (1638 – 1661), for monks, nuns, and laity to chant during morning liturgical services.[95] This set of mantras is still chanted in modern Chinese Buddhism.[96]

Zen Buddhism also makes use of esoteric mantras, a practice which can be traced back to the Tang dynasty. Mantras and dharanis are recited in all Zen traditions, including Japanese Zen, Korean Seon, Chinese Chan and Vietnamese Thien. One of these is the Śūraṅgama Dharani, which has been taught by various modern Chan and Zen monks, such as Venerable Hsuan Hua.[97] This long dharani is associated with the protective deity Sitatpatra. The short heart mantra of this dharani is also popular in East Asian Buddhism.

Shaolin temple monks also made use of esoteric mantras and dharani.[98]

Chinese Mantrayana and Japanese Shingon

Chinese Esoteric Buddhism also known as Zhēnyán (Chinese: 真言, lit. "true word", which is the translation for "mantra") draws extensively on mantras. This tradition was established during the Tang dynasty by Indian tantric masters like Śubhakarasiṃha, Vajrabodhi and Amoghavajra. Chinese esoteric Buddhist practice was based on deity yoga and the "three mysteries": mantra, mudra and mandala. These three mysteries allow the Buddhist yogi to tap into the body, speech and mind of the Buddhas.[99]

This tradition was transmitted to Japan by Kūkai (774–835), who founded the Japanese Shingon (Japanese for Zhēnyán) mantra vehicle. Kūkai saw a mantra as a manifestation of the true nature of reality which is saturated with meaning. For Kūkai, a mantra is nothing but the speech of the Buddha Mahavairocana, the "ground dharmakaya" which is the ultimate source of all reality. According to Kūkai, Shingon mantras contain the entire meaning of all the scriptures and indeed the entire universe (which is itself the sermon of the Dharmakaya).[100] Kūkai argues that mantras are effective because: "a mantra is suprarational; It eliminates ignorance when meditated upon and recited. A single word contains a thousand truths; One can realize Suchness here and now."[101]

One of Kūkai's distinctive contributions was to take this symbolic association even further by saying that there is no essential difference between the syllables of mantras and sacred texts, and those of ordinary language. If one understood the workings of mantra, then any sounds could be a representative of ultimate reality. This emphasis on sounds was one of the drivers for Kūkai's championing of the phonetic writing system, the kana, which was adopted in Japan around the time of Kūkai. He is generally credited with the invention of the kana, but there is apparently some doubt about this story amongst scholars.

This mantra-based theory of language had a powerful effect on Japanese thought and society which up until Kūkai's time had been dominated by imported Chinese culture of thought, particularly in the form of the Classical Chinese language which was used in the court and amongst the literati, and Confucianism which was the dominant political ideology. In particular, Kūkai was able to use this new theory of language to create links between indigenous Japanese culture and Buddhism. For instance, he made a link between the Buddha Mahavairocana and the Shinto sun Goddess Amaterasu. Since the emperors were thought to be descended form Amaterasu, Kūkai had found a powerful connection here that linked the emperors with the Buddha, and also in finding a way to integrate Shinto with Buddhism, something that had not happened with Confucianism. Buddhism then became essentially an indigenous religion in a way that Confucianism had not. And it was through language and mantra that this connection was made. Kūkai helped to elucidate what mantra is in a way that had not been done before: he addresses the fundamental questions of what a text is, how signs function, and above all, what language is. In this, he covers some of the same ground as modern day Structuralists and others scholars of language, although he comes to very different conclusions.

In this system of thought, all sounds are said to originate from "a". For esoteric Buddhism "a" has a special function because it is associated with Shunyata or the idea that no thing exists in its own right, but is contingent upon causes and conditions. (See Dependent origination) In Sanskrit "a" is a prefix which changes the meaning of a word into its opposite, so "vidya" is understanding, and "avidya" is ignorance (the same arrangement is also found in many Greek words, like e.g. "atheism" vs. "theism" and "apathy" vs. "pathos"). The letter a is both visualised in the Siddham script and pronounced in rituals and meditation practices. In the Mahavairocana Sutra which is central to Shingon Buddhism it says: "Thanks to the original vows of the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas, a miraculous force resides in the mantras, so that by pronouncing them one acquires merit without limits". [in Conze, p. 183]

A mantra is Kuji-kiri in Shingon as well as in Shugendo. The practice of writing mantras, and copying texts as a spiritual practice, became very refined in Japan, and some of these are written in the Japanese script and Siddham script of Sanskrit, recited in either language.

Main Shingon Mantras

There are thirteen mantras used in Shingon Buddhism, each dedicated to a major deity (the "thirteen Buddhas" - jūsanbutsu - of Shingon). The mantras are drawn from the Vairocanābhisaṃbodhi Sūtra. The mantra for each deity name in Japanese, its equivalent name in Sanskrit, the Sanskrit mantra, and the Japanese version in the Shingon tradition are as follows:[102]

- Fudōmyōō (不動明王, Acala): Sanskrit: namaḥ samanta vajrāṇāṃ caṇḍa mahāroṣaṇa sphoṭaya hūṃ traṭ hāṃ māṃ (Shingon transliteration: nōmaku samanda bazaratan senda makaroshada sowataya untarata kanman)

- Shaka nyorai (釈迦如来, Sakyamuni): namaḥ samanta buddhānāṃ bhaḥ (nōmaku sanmanda bodanan baku)

- Monju bosatsu (文殊菩薩, Manjushri): oṃ a ra pa ca na (on arahashanō)

- Fugen bosatsu (普賢菩薩, Samantabhadra): oṃ samayas tvaṃ (on sanmaya satoban)

- Jizō bosatsu (地蔵菩薩, Ksitigarbha): oṃ ha ha ha vismaye svāhā (on kakaka bisanmaei sowaka)

- Miroku bosatsu (弥勒菩薩, Maitreya): oṃ maitreya svāhā (on maitareiya sowaka)

- Yakushi nyorai (薬師如来, Bhaisajyaguru): oṃ huru huru caṇḍāli mātangi svāhā (on korokoro sendari matōgi sowaka)

- Kanzeon bosatsu (観世音菩薩, Avalokitesvara): oṃ ārolik svāhā (on arorikya sowaka)

- Seishi bosatsu (勢至菩薩, Mahasthamaprapta): oṃ saṃ jaṃ jaṃ saḥ svāhā (on san zan saku sowaka)

- Amida nyorai (阿弥陀如来, Amitabha): oṃ amṛta teje hara hūṃ (on amirita teisei kara un)

- Ashuku nyorai (阿閦如来, Akshobhya): oṃ akṣobhya hūṃ (on akishubiya un)

- Dainichi nyorai (大日如来, Vairocana): oṃ a vi ra hūṃ khaṃ vajradhātu vaṃ (on abiraunken basara datoban)

- Kokūzō bosatsu (虚空蔵菩薩, Akashagarbha): namo ākāśagarbhāya oṃ ārya kāmāri mauli svāhā (nōbō akyashakyarabaya on arikya mari bori sowaka)

Other Japanese Buddhist traditions

Mantras are also an important element of other Japanese Buddhist traditions. The Tendai school includes extensive repertoire of Esoteric Buddhist practices, which include the use of mantras.

Nichiren Buddhist practice focuses on the chanting of one single mantra or phrase: Nam Myōhō Renge Kyō (南無妙法蓮華経, which means "Homage to the Lotus Sutra").

Japanese Zen also makes use of mantras. One example is the Mantra of Light (kōmyō shingon), which is common in Japanese Soto Zen and was derived from the Shingon sect.[103] The use of esoteric practices (such as mantra) within Zen is sometimes termed "mixed Zen" (kenshū zen 兼修禪). Keizan Jōkin (1264–1325) is seen as a key figure that introduced this practice into the Soto school.[104][105] A common mantra used in Soto Zen is the Śūraṅgama mantra (Ryōgon shu 楞嚴呪; T. 944A).

In Northern Vajrayana Buddhism

Mantrayana (Sanskrit), which may be translated as "way of the mantra", was the original self-identifying name of those that have come to be determined 'Nyingmapa'.[106] The Nyingmapa which may be rendered as "those of the ancient way", a name constructed due to the genesis of the Sarma "fresh", "new" traditions. Mantrayana has developed into a synonym of Vajrayana.

According to the important Mantrayana Buddhist text called the Mañjuśrīmūlakalpa, mantras are efficacious because they are manifestations of the Buddhas and bodhisattvas. As such, a mantra is coextensive with the bodies of the Buddhas and bodhisattvas. When one recites a mantra, one's mind is coextensive with the mantras, and thus, one's mind makes a connection with the mantra's deity and their meditative power (samadhi-bala).

Om mani padme hum

Probably the most famous mantra of Buddhism is Om mani padme hum, the six syllable mantra of the Bodhisattva of compassion Avalokiteśvara (Tibetan: Chenrezig, Chinese: Guanyin). This mantra is particularly associated with the four-armed Shadakshari form of Avalokiteśvara. The Dalai Lama is said to be an incarnation of Avalokiteshvara, and so the mantra is especially revered by his devotees.

The book Foundations of Tibetan Mysticism by Lama Anagarika Govinda, gives a classic example of how such a mantra can contain many levels of symbolic meaning.

Other

The following list of mantras is from Kailash: A Journal of Himalayan Studies, Volume 1, Number 2, 1973. (pp. 168–169) (augmented by other contributors). The mantras used in Tibetan Buddhist practice are in Sanskrit, to preserve the original mantras. Visualizations and other practices are usually done in the Tibetan language.

- Om vagishvara hum This is the mantra of the Mahabodhisattva Manjusri, Tibetan: Jampelyang (Wylie "'jam dpal dbyangs")... The Buddha in his wisdom aspect.

- Om vajrasattva hum The short mantra for White Vajrasattva, there is also a full 100-syllable mantra for Vajrasattva.

- Om vajrapani namo hum The mantra of the Buddha as Protector of the Secret Teachings. i.e.: as the Mahabodhisattva Channa Dorje (Vajrapani).

- Om ah hum vajra guru padma siddhi hum The mantra of the Vajraguru Guru Padma Sambhava who established Mahayana Buddhism and Tantra in Tibet.

- Om tare tuttare ture mama ayurjnana punye pushting svaha The mantra of Dölkar or White Tara, the emanation of Arya Tara [Chittamani Tara]. Variants: Om tare tuttare ture mama ayurjnana punye pushting kuru swaha (Drikung Kagyu), Om tare tuttare ture mama ayu punye jnana puktrim kuru soha (Karma Kagyu).

- Om tare tuttare ture svaha, mantra of Green Arya Tara—Jetsun Dolma or Tara, the Mother of the Buddhas: om represents Tara's sacred body, speech, and mind. Tare means liberating from all discontent. Tutare means liberating from the eight fears, the external dangers, but mainly from the internal dangers, the delusions. Ture means liberating from duality; it shows the "true" cessation of confusion. Soha means "may the meaning of the mantra take root in my mind."

According to Tibetan Buddhism, this mantra (Om tare tutare ture soha) can not only eliminate disease, troubles, disasters, and karma, but will also bring believers blessings, longer life, and even the wisdom to transcend one's circle of reincarnation. Tara representing long life and health.

- Oṃ amaraṇi jīvantaye svāhā (Tibetan version: oṃ ā ma ra ṇi dzi wan te ye svā hā) The mantra of the Buddha of limitless life: the Buddha Amitayus (Tibetan Tsépagmed) in celestial form.

- Om dhrung svaha The purification mantra of the mother Namgyalma.

- Om ami dhewa hri The mantra of the Buddha Amitabha (Hopagmed) of the Western Pureland, his skin the color of the setting sun.

- Om ami dewa hri The mantra of Amitabha (Ompagme in Tibetan).

- Om ah ra pa ca na dhih The mantra of the "sweet-voiced one", Jampelyang (Wylie "'jam dpal dbyangs") or Manjusri, the Bodhisattva of wisdom.

- Om muni muni maha muniye sakyamuni swaha The mantra of Buddha Sakyamuni, the historical Buddha

- Om gate gate paragate parasamgate bodhi svaha The mantra of the Heart of the Perfection of Wisdom Sutra (Heart Sutra)

- Namo bhagavate Bhaishajya-guru vaidurya-praba-rajaya tathagataya arhate samyak-sambuddhaya tadyata *Tadyata OM bhaishajye bhaishajye maha bhaishajya raja-samudgate svaha The mantra of the 'Medicine Buddha', Bhaiṣajya-guru (or Bhaishajyaguru), from Chinese translations of the Master of Healing Sutra.

In Bon

There are also numerous mantras in the Bön religion such as Om Ma Tri Mu Ye Sa Le Du.[107]

Zoroastrianism

In Zoroastrianism, the use of mantras (Avestan: mąθra) goes back to Zarathustra himself, who describes his role as a prophet of the creator deity Ahura Mazda explicitly as a knower of mantras (Avestan: mąθran; Sanskrit: mántrin). In the Zoroastrian tradition, a mantra is usually a shorter inspired utterance that accompanies religious rituals. They differ from the longer, often eight-syllable praise songs (called Yasht in the Avesta) as well as the often eleven-syllable songs (called Gathas in the Avesta as well as in the Vedas).[108]

The four most important Zoroastrian mantras are the Ahuna Vairya, the Ashem Vohu, the Yenghe hatam, and the Airyaman ishya. The Ashem Vohu states:

aṣ̌əm vohū vahištəm astī

uštā astī uštā ahmāi

hyat̰ aṣ̌āi vahištāi aṣ̌əm

Holiness (Asha) is the best of all good:

it is also happiness.

Happy the man who is holy with perfect holiness!

— Ashem Vohu.[109]

Both Vedic and Avestan mantras have a number of functional similarities. One of these is the idea that truth, when properly expressed in the mantra, can compel a deity to grant the speaker's request(compare Sacca-kiriya). Another similarity is the Vedic and Avestic association of mantras with paths, so that a properly formulated mantra can open a path to the deity addressed.[110] Because of the etymological and conceptual similarity, such religious utterances must therefore have already been known during the common Indo-Iranian period, when the people of the Avesta and of the Vedas formed a single people.[111] They are, therefore, not derived from the Vedic tradition, but represent an independent development of ancient Iran, corresponding to that in ancient India.[112] The study of their commonalities is therefore important for understanding the poetic and religious traditions of the early Indo-Iranians.[10]

Jainism

In Jainism mantras are mainl used for praising the omniscient enlightened ones (Arihants), or praising the five supreme types of beings (Pañca-Parameṣṭhi). Some mantras are also used for seeking forgiveness, or to enhance intellect, prosperity, wealth or fame. There are many mantras in Jainism; most of them are in Sanskrit or Prakrit, but in the last few centuries, some have been composed in Hindi or Gujrati languages. Mantras, couplets, are either chanted or sung, either aloud or by merely moving lips or in silence by thought.[113]

Namokar

Some examples of Jain mantras are Bhaktamara Stotra, Uvasagharam Stotra and Rishi Mandal Mantra. The greatest is the Namokar or Namokar Mantra.[114] Acharya Sushil Kumar, a self-realized master of the secrets of the Mantra, wrote in 1987: "There is a deep, secret science to the combination of sounds. Specific syllables are seeds for the awakening of latent powers. Only a person who has been initiated into the vibrational realms, who has actually experienced this level of reality, can fully understand the Science of Letters...the Nomokar Mantra is a treasured gift to humanity of unestimable (sic) worth for the purification, upliftment and spiritual evolution of everyone.".[115] His book, The Song of the Soul, is a practical manual to unlock the secrets of the mantra. "Chanting with Guruji" is a compilation of well-known Jain mantras, including the Rishi Mandal Mantra.[116]

The Navkar Mantra (literally, "Nine Line Mantra") is the central mantra of Jainism. "It is the essence of the gospel of the Tirthankars."[117] The initial 5 lines consist of salutations to various purified souls, and the latter 4 lines are explanatory in nature, highlighting the benefits and greatness of this mantra.

According to the timeperiods of this world or the Kaals , we are living in the era of Pancham Kaal or Fifth Kaal. It started 4 months after the Nirvana of the last tirthankar of Jainism , Mahaveer Swami. In the Pancham Kaal we are only eligible to know these basic 5 lines and the concluding 4 lines of the Namokar Mantra , but it is believed that the mantra exceeds till infinity. If it is chanted with complete faith , it could even do or undo the impossible. Jains also believe that it is the elementary form of all other Mantras. It is renowned as the King of all Mantras . It is also held that even the Mantras of other ancient religions like Hinduism & Buddhism are also derived from the Navkar Mantra. Indeed, it is held that 8.4 million Mantras have been derived from the Navkar Mantra.

The Mantra is as follows (Sanskrit, English):

Namo Arihantânam I bow to the Arihantâs (Conquerors who showed the path of liberation). Namo Siddhânam I bow to the Siddhâs (Liberated Souls). Namo Âyariyânam I bow to the Âchâryas (Preceptors or Spiritual Leaders). Namo Uvajjhâyanam I bow to the Upadhyâya (Teachers). Namo Loe Savva Sahûnam I bow to all the Sadhûs in the world (Saints or Sages). Eso Panch Namokkaro,

Savva Pâvappanâsano,

Mangalanam Cha Savvesim,

Padhamam Havai Mangalam.This fivefold salutation (mantra) destroys all sins

and of all auspicious mantras, (it) is the foremost.One of the best approach to chant the Namokar Mantra while keeping in mind the flow of the chakras is to focus on each chakra as you recite each phrase of the mantra . Here is a suggested sequence :

1. Begin by taking a few deep breaths and focusing your attention on the base of your spine, where the first chakra (Muladhara) is located. As you inhale, imagine energy flowing up from the earth and into your root chakra.

2. As you recite "Namo Arihantanam," visualize a bright white light at the base of your spine and feel the energy rising up through your body while bowing to all Arihants at the Same Time.

3. As you recite "Namo Siddhanam," focus on your second chakra (Svadhisthana), located in the lower abdomen. Visualize a warm orange light here, and feel the energy of creativity while bowing to all Siddhas.

4. As you recite "Namo Ayariyanam," bring your attention to your third chakra (Manipura), located in the solar plexus. Imagine a bright yellow light here, representing personal power and will while bowing to all Arihants at the same Time.

5. As you recite "Namo Uvajhayanam," focus on your fourth chakra (Anahata), located in the center of your chest. Visualize a green light here, representing love and compassion while bowing to all Upadhayas at the Same time.

6. As you recite "Namo Loye Savva Sahunam," bring your attention to your fifth chakra (Vishuddha), located in the throat. Imagine a blue light here representing communication and self- expression while bowing to all Sadhus in the Dhai Dweep.

7. As you recite "Eso Panch Namukaro," focus on your sixth chakra (Ajna), located in the center of your forehead Visualize a deep purple light here representing intuition and spiritual insight.

8. Finally, as you recite "Savva Pavappanasano," bring your attention to your seventh chakra (Sahasrara), located at the crown of your head. Imagine a bright white light here, representing spiritual enlightenment and connection to the divine entity.

Repeat the mantra several times, moving

your awareness up through each chakra

with each phrase. This can help to

balance and activate your energy centers.

Universal compassion

Pratikraman also contains the following prayer:[118]

Khāmemi savva-jīve savvë jive khamantu me I ask pardon of all creatures, may all creatures pardon me. Mitti me savva-bhūesu, veraṃ mejjha na keṇavi May I have a friendship with all beings and enemy with none.

Forgiveness

Forgiveness is one of the main virtues Jains cultivate. Kṣamāpanā, or supreme forgiveness, forms part of one of the ten characteristics of dharma.[119]

In the pratikramana prayer, Jains repeatedly seek forgiveness from various creatures—even from ekindriyas or single sensed beings like plants and microorganisms that they may have harmed while eating and doing routine activities.[120] Forgiveness is asked by uttering the phrase, Micchāmi dukkaḍaṃ. Micchāmi dukkaḍaṃ is a Prakrit phrase literally meaning "may all the evil that has been done be fruitless."[121]

In their daily prayers and samayika, Jains recite the following Iryavahi sutra in Prakrit, seeking forgiveness from literally all creatures while involved in routine activities:[122]

May you, O Revered One, voluntarily permit me. I would like to confess my sinful acts committed while walking. I honour your permission. I desire to absolve myself of the sinful acts by confessing them. I seek forgiveness from all those living beings which I may have tortured while walking, coming and going, treading on a living organism, seeds, green grass, dew drops, ant hills, moss, live water, live earth, spider web and others. I seek forgiveness from all these living beings, be they one sensed, two sensed, three sensed, four sensed or five sensed, which I may have kicked, covered with dust, rubbed with earth, collided with other, turned upside down, tormented, frightened, shifted from one place to another or killed and deprived them of their lives. (By confessing) may I be absolved of all these sins.

Sikhism

In the Sikh religion, a mantar or mantra is a Shabad (Word or hymn) from the Adi Granth to concentrate the mind on God. Through repetition of the mantra, and listening to one's own voice, thoughts are reduced and the mind rises above materialism to tune into the voice of God.

Mantras in Sikhism are fundamentally different from the secret mantras used in other religions.[123] Unlike in other religions, Sikh mantras are open for anyone to use. They are used openly and are not taught in secret sessions but are used in front of assemblies of Sikhs.[123]

The Mool Mantar, the first composition of Guru Nanak, is the second most widely known Sikh mantra.

The most widely known mantra in the Sikh faith is "Wahe Guru." According to the Sikh poet Bhai Gurdas, the word "Wahe Guru" is the Gurmantra, or the mantra given by the Guru, and eliminates ego.[124]

According to the 10th Sikh Master, Guru Gobind Singh, the "Wahe Guru" mantra was given by God to the Order of the Khalsa, and reforms the apostate into the purified.

Chinese religions

The influence of Chinese Esoteric Buddhism during the Six Dynasties period and the Tang led to the widespread use of Buddhist esoteric practices in other Chinese religions such as Taoism. This included the use of mantras.[125] Mantras are often still used in Chinese Taoism, such as the words in Dàfàn yǐnyǔ wúliàng yīn (大梵隱語無量音), the recitation of a deity's name. Another example of a Taoist mantra is found in one of the most popular liturgies in Taoism (dating from the Tang dynasty), the Pei-tou yen-sheng ching (The North Star Scripture of Longevity), which contains a long mantra called the "North Star Mantra." The text claims that this mantra "can deliver you from disaster," "ward off evil and give you prosperity and longevity," "help you accumulate good deeds" and give you peace of mind.[126]

The Indian syllable om (唵) is also used in Taoist esotericism. After the arrival of Buddhism many Taoist sects started to use Sanskrit syllables in their mantras or talisman as a way to enhance one's spiritual power aside from the traditional Han incantations. One example of this is the "heart mantra" of Pu Hua Tian Zun (普化天尊), a Taoist deity manifested from the first thunder and head of the "36 thunder gods" in orthodox religious Taoism. His mantra is "Ǎn hōng zhā lì sà mó luō - 唵吽吒唎薩嚩囉". Taoist believe this incantation to be the heart mantra of Pu Hua Tian Zun which will protect them from bad qi and calm down emotions. Taoist mantra recitation may also be practiced along with extensive visualization exercises.[127]

There are also mantras in Cheondoism, Daesun Jinrihoe, Jeung San Do and Onmyōdō.[128]

Other Chinese religions have also adopted the use of mantras.[129][130][131] These include:

- Námó Tiānyuán Tàibǎo Āmítuófó (南無天元太保阿彌陀佛) The mantra of Xiantiandao and Shengdao in Chinese.

- Wútàifó Mílè (無太佛彌勒) The mantra of Yiguandao[132] in Chinese.

- Guānshìyīn Púsà (觀世音菩薩) The mantra of the Li-ism[133][134] in Chinese.

- Zhēnkōng jiāxiàng, wúshēng fùmǔ (真空家鄉,無生父母) The mantra of the Luojiao[135][136] in Chinese.

- Zhōng Shù Lián Míng Dé, Zhèng Yì Xìn Rěn Gōng, Bó Xiào Rén Cí Jiào, Jié Jiǎn Zhēn Lǐ Hé (忠恕廉明德,正義信忍公,博孝仁慈覺,節儉真禮和) The mantra of the Tiender and the Lord of Universe Church[137] in Chinese.

- Qīngjìng Guāngmíng Dàlì Zhìhuì Wúshàng Zhìzhēn Móní Guāngfó (清淨光明大力智慧無上至真摩尼光佛) The mantra of the Manichaeism in Chinese.

See also

Notes

- ^ "mantra" Archived 18 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Jan Gonda (1963). The Indian Mantra. Vol. 16. Oriens. pp. 244–297.

- ^ a b Feuerstein, Georg (2003), The Deeper Dimension of Yoga. Shambala Publications, Boston, MA

- ^ James Lochtefeld, The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Volume 2, ISBN 0-8239-2287-1, pages 422–423

- ^ a b c d Alper, Harvey (1991). Understanding mantras. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0746-4. OCLC 29867449.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Frits Staal (1996). Rituals and Mantras, Rules without meaning. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-1412-7.

- ^ Nesbitt, Eleanor M. (2005), Sikhism: a very short introduction, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-280601-7

- ^ a b Goudriaan, Teun (1981). Hindu tantric and Śākta literature. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. p. Chapter VIII. ISBN 978-3-447-02091-6. OCLC 7743718.

- ^ Boyce, M. (2001), Zoroastrians: their religious beliefs and practices, Psychology Press

- ^ a b Schmitt, Rüdiger (16 August 2011) [15 December 1987]. "Aryans". Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. II. Iranica Foundation. pp. 684–687. Archived from the original on 13 June 2024.

- ^ Monier-Williams, Monier (1992) [1899]. A Sanskrit-English dictionary etymologically and philologically arranged with special reference to cognate Indo-European languages;. Leumann, Ernst, Cappeller, Carl (New ed.). Oxford: The Clarendon Press. p. 787.1. ISBN 81-215-0200-4. OCLC 685239912.

- ^ "Mantra Definition & Meaning". Merriam-Webster. Archived from the original on 31 March 2019. Retrieved 4 May 2019.

- ^ Macdonell, Arthur A., A Sanskrit Grammar for Students § 182.1.b, p. 162 (Oxford University Press, 3rd edition, 1927).

- ^ Whitney, W. D., Sanskrit Grammar § 1185.c, p. 449(New York, 2003, ISBN 0-486-43136-3).

- ^ "Mantra". Etymonline. Archived from the original on 4 May 2019. Retrieved 4 May 2019.

- ^ Gonda, Jan (1963). "The Indian Mantra". Oriens. 16: 244–297. doi:10.2307/1580265. JSTOR 1580265.

- ^ Sadovski, Velizar (2009). "Ritual formulae and ritual pragmatics in Veda and Avesta". Die Sprache. 48.

Thus the comparative evidence of Avestan and Vedic exhibits hidden residues of old mantras and magic actions which can enlarge our knowledge of older (Indo-Iranian) magic formulae and magic rituals in an essential way.

- ^ Law, Jane Marie (1995). Religious Reflections on the Human Body. Indiana University Press. pp. 173–174. ISBN 0-253-11544-2. Archived from the original on 15 July 2019. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- ^ Alex Wayman; Ryujun Tajima (1992). The Enlightenment of Vairocana. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 225, 254, 293–294. ISBN 978-81-208-0640-5. Archived from the original on 8 July 2019. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- ^ Schlerath, Bernfried (1987). ""Aša: Avestan Aša"". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Vol. 2. New York: Routledge. pp. 694–696.

- ^ Harvey Alper (1989), Understanding Mantras, ISBN 81-208-0746-4, State University of New York, pages 3–7

- ^ "Mantra" Archived 7 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Oxford Living Dictionary.

- ^ "Mantra" Archived 29 June 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Cambridge Dictionary.

- ^ T Renou (1946), Littérature Sanskrite, Paris, page 74

- ^ L. Silburn (1955), Instant et cause, Paris, page 25

- ^ J. Farquhar (1920), An outline of the religious literature of India, Oxford, page 25

- ^ Heinrich Robert Zimmer (1946), Myths and symbols in Indian art and civilization, ISBN 978-0-691-01778-5, Washington DC, page 72

- ^ a b Agehananda Bharati (1965), The Tantric Tradition, London: Rider and Co., ISBN 0-8371-9660-4

- ^ Harvey Alper (1989), Understanding Mantras, ISBN 81-208-0746-4, State University of New York, page 9

- ^ Jan Gonda (1975), Vedic Literature (Samhitäs and Brähmanas), (HIL I.I) Wiesbaden: OH; also Selected Studies, (4 volumes), Leiden: E. J. Brill

- ^ This is a Buddhist chant. The words in Pali are: Buddham saranam gacchami, Dhammam saranam gacchami, Sangham saranam gacchami. The equivalent words in Sanskrit, according to Georg Feuerstein, are: Buddham saranam gacchâmi, Dharmam saranam gacchâmi, Sangham saranam gacchâmi. The literal meaning: I go for refuge in Buddha, I go for refuge in Buddhist teachings, I go for refuge in Buddhist Monastics.

- ^ Frits Staal (1985), Mantras and Bird Songs, Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 105, No. 3, Indological Studies, pages 549–558

- ^ Harvey Alper (1989), Understanding Mantras, ISBN 81-208-0746-4, State University of New York, pages 10–11

- ^ Frits Staal (1996), Rituals and Mantras, Rules without meaning, ISBN 978-81-208-1412-7, Motilal Banarsidass, pages 112–113

- ^ Harvey Alper (1989), Understanding Mantras, ISBN 81-208-0746-4, State University of New York, pages 10–14

- ^ Andre Padoux, in Understanding Mantras, ISBN 81-208-0746-4, State University of New York, pages 295–317; see also Chapter 3 by Wade Wheelock

- ^ Harvey Alper (1989), Understanding Mantras, ISBN 81-208-0746-4, State University of New York, pages 11–13

- ^ a b Frits Staal (1996), Rituals and Mantras, Rules without meaning, ISBN 978-81-208-1412-7, Motilal Banarsidass, Chapter 20

- ^ "Chapter 65". Linga Mahapurana. Vol. I. Translated by Lal Nagar, Shanti. Delhi, India: Parimal Publications. 2011. p. 259. ISBN 978-81-7110-391-1. OCLC 753465312.

- ^ Lochtefeld, James G. "Samhita" in The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Vol. 2: N-Z, Rosen Publishing, ISBN 0-8239-2287-1, page 587

- ^ a b "Vedic Heritage". vedicheritage.gov.in/. Retrieved 18 February 2021.

- ^ Jan Gonda (1963), The Indian Mantra, Oriens, Vol. 16, pages 258–259

- ^ Jan Gonda (1980), Vedic Ritual: The non-Solemn Rites, Amsterdam; see also Jan Gonda (1985), The Ritual Functions and Significance of Grasses in the Religion of the Veda, Amsterdam; Jan Gonda (1977), The Ritual Sutras, Wiesbaden

- ^ P.V. Kane (1962), History of Dharmasastra, Volume V, part II

- ^ Harvey Alper (1989), Understanding Mantras, ISBN 81-208-0746-4, State University of New York, see Introduction

- ^ Harvey Alper (1989), Understanding Mantras, ISBN 81-208-0746-4, State University of New York, pages 7–8

- ^ a b Harvey Alper (1989), Understanding Mantras, ISBN 81-208-0746-4, State University of New York, Chapter 10

- ^ Swami, Om (2017). The ancient science of Mantras. Jaico Publications. ISBN 978-93-86348-71-5.

- ^ Stutley & Stutley 2002, p. 126.

- ^ a b Monier Monier-Williams (1893), Indian Wisdom, Luzac & Co., London, pages 245–246, see text and footnote

- ^ Radha, Swami Sivananda (2005). Mantras: Words of Power. Canada: Timeless Books. p. 54. ISBN 978-1-932018-10-3. Archived from the original on 5 April 2014. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

Mantra Yoga (chanting), Japa Yoga: Vaikhari Japa (speaking), Upamsu Japa (whispering or humming), Manasika Japa (mental repetition), Likhita Japa (writing)

- ^ Some very common mantras, called Nama japa, are: "Om Namah (name of deity)"; for example, Om Namah Shivaya or Om Namo Bhagavate Rudraya Namah (Om and salutations to Lord Shiva); Om Namo Narayanaya or Om Namo Bhagavate Vasudevãya (Om and salutations to Lord Vishnu); Om Shri Ganeshaya Namah (Om and salutations to Shri Ganesha)

- ^ Vishnu-Devananda 1981, p. 66.

- ^ A Dictionary of Hinduism, p.271; Some of the major books which are used as reference for Mantra Shaastra are: Parasurama Kalpa Sutra; Shaarada Tilakam; Lakshmi Tantra; Prapanchasara

- ^ Ananda Lal (2009). Theatres of India: A Concise Companion. Oxford University Press. pp. 423–424. ISBN 978-0-19-569917-3.

- ^ Sara Brown (2012), Every Word Is a Song, Every Step Is a Dance, PhD Thesis, Florida State University (Advisor: Michael Bakan), pages 25-26, 87-88, 277

- ^ Alanna Kaivalya (2014). Sacred Sound: Discovering the Myth and Meaning of Mantra and Kirtan. New World. pp. 3–17, 34–35. ISBN 978-1-60868-244-7.

- ^ Manohar Laxman Varadpande (1987). History of Indian Theatre. Abhinav. pp. 95–96. ISBN 978-81-7017-278-9.

- ^ Spencer, L. (2015). Flotation: A Guide for Sensory Deprivation, Relaxation, & Isolation Tanks. ISBN 1-329-17375-9, ISBN 978-1-329-17375-0, p. 57.

- ^ Gudrun Bühnemann, Selecting and perfecting mantras in Hindu tantrism, Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies / Volume 54 / Issue 02 / June 1991, pages 292–306

- ^ David Gordon White (2000), Tantra in Practice, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-05779-8

- ^ Jean Herbert, Spiritualite hindoue, Paris 1947, ISBN 978-2-226-03298-0

- ^ Bhattāchārya, Majumdar and Majumdar, Principles of Tantra, ISBN 978-81-85988-14-6, see Introduction by Barada Kanta Majumdar

- ^ Brooks (1990), The Secret of the Three Cities: An Introduction to Hindu Sakta Tantrism, University of Chicago Press

- ^ David Gordon White (Editor) (2001), Tantra in practice (Vol. 8), Motilal Banarsidass, Princeton Readings in Religions, ISBN 978-81-208-1778-4, Chapters 21 and 31

- ^ a b Monier Monier-Williams (1893), Indian Wisdom, Luzac & Co., London, page 17

- ^ Meditation and Mantras, p.75

- ^ Brhadaranyaka-Upanisad (Brhadaranyakopanisad), Kanva recension; GRETIL version, input by members of the Sansknet project (formerly: www.sansknet.org) Archived 19 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Balfour, Edward (1968). The Cyclopaedia of India and of Eastern and Southern Asia. Akademische Druck-u. Verlagsanstalt. p. 23.

- ^ Siva Sutras: The Yoga of Supreme Identity, by Vasugupta, translation (PDF). Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. 1979. ISBN 978-81-208-0406-7. OCLC 597890946. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 April 2015. Retrieved 22 March 2015 – via bibleoteca.narod.ru.

- ^ Beck, G.L. (1995). Sonic Theology: Hinduism and Sacred Sound. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. p. 165.

- ^ Singh, J. (2012). Siva Sutras: The Yoga of Supreme Identity. ISBN 978-81-208-0407-4

- ^ Gergely Hidas (2014). Two dhāranī prints in the Stein Collection at the British Museum. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, 77, pp 105-117 doi:10.1017/ S0041977X13001341

- ^ "A New Document of Indian Painting Pratapaditya Pal". The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland (3/4): 103–111. October 1965. JSTOR 25202861.

- ^ On the miniature chaityas, Lieut.-Col. Sykes, Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, Volume 16, By Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, University Press, 1856

- ^ Anandajoti Bhikkhu (edition, trans.) (2004). Safeguard Recitals, p. v. Kandy: Buddhist Publication Society. ISBN 955-24-0255-7.

- ^ Kornfield, Jack. Living Dharma: Teachings and Meditation Instructions from Twelve Theravada Masters, chapter seventeen. Shambhala Publications, 12 Oct 2010.

- ^ Kornfield, j. Modern Buddhist masters, pg 311.

- ^ Ajahn Chah, Clarity of Insight, "Clarity Insight". Archived from the original on 2 June 2015. Retrieved 21 May 2015.

- ^ Stede, William (1993). Rhys Davids, T. W. (ed.). The Pali-English dictionary (1. Indian ed.). New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 81-208-1144-5. Archived from the original on 25 May 2017. Retrieved 25 May 2017.

- ^ Desaransi, Phra Ajaan Thate (2 November 2013). "Buddho". Access to Insight (Legacy Edition). Translated by Thanissaro, Bhikkhu. Archived from the original on 13 May 2017. Retrieved 25 May 2017.

- ^ "A mini reference archive library of compiled Buddhist Katha/Katta". Mir.com.my. Archived from the original on 26 June 2012. Retrieved 17 July 2012.

- ^ Robert E. Buswell and Donald S. Lopez (2014). The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism, pp. 1, 24. Published by Princeton University Press

- ^ Conze, Edward (1975). The Large Sutra on Perfect Wisdom with the divisions of the Abhisamayālañkāra, Archived 2021-05-06 at the Wayback Machine p. 160. University of California Press.

- ^ a b c Jayarava, Visible Mantra: Visualising & Writing Buddhist Mantras, pp. 35-43. 2011.

- ^ Ithamar Theodor, Zhihua Yao (2013). Brahman and Dao: Comparative Studies of Indian and Chinese Philosophy and Religion, pp. 215. Lexington Books

- ^ www.wisdomlib.org (29 August 2018). "The forty-two letters of the Arapacana alphabet [Appendix 3]". www.wisdomlib.org. Retrieved 9 February 2023.

- ^ see: Ajitasenavyākaraṇa, Buddhacarita,

- ^ see: Ratnāvalī, Kāraṇḍavyūha, Maṃjuśrīpārājikā

- ^ Conze, Edward. Perfect Wisdom: The Short Prajñāpāramitā Texts, p. 145. Buddhist Publishing Group, 1993.

- ^ Shōtarō Iida; Goldstone, Jane; McRae, John R. (tr.) The Sutra That Expounds the Descent of Maitreya Buddha and His Enlightenment / The Sutra of Manjusri's Questions, p. 136. Bukkyō Dendō Kyōkai America, Incorporated, 2016.

- ^ "Kauśikaprajñāpāramitāsūtram - Digital Sanskrit Buddhist Canon". www.dsbcproject.org. Retrieved 8 November 2023.

- ^ "Saddharmapuṇḍarīka - Thesaurus Literaturae Buddhicae - Bibliotheca Polyglotta". www2.hf.uio.no. Retrieved 13 November 2023.

- ^ "Pinyin of ten mantras". 24 March 2007. Archived from the original on 24 March 2007. Retrieved 17 July 2012.

- ^ "Ten Small Mantras". www.buddhamountain.ca. Retrieved 10 July 2021.

- ^ Buddhist Text Translation Society (2013), Daily Recitation Handbook: Sagely City of 10,000 Buddhas

- ^ Keyworth, George A. (2016). "Zen and the "Hero's March Spell" of the Shoulengyan jing". The Eastern Buddhist. 47 (1): 81–120. ISSN 0012-8708. JSTOR 26799795.

- ^ Orzech, Sørensen & Payne 2011, p. 589.

- ^ Orzech, Charles; Sørensen, Henrik; Payne, Richard Karl (2011). Esoteric Buddhism and the Tantras in East Asia. BRILL. doi:10.1163/ej.9789004184916.i-1200. ISBN 978-90-04-20401-0. OCLC 731667667.

- ^ Hakeda, Yoshito S., transl. (1972). Kukai: Major Works, Translated, With an Account of His Life and a Study of His Thought, pp. 78-79. New York: Columbia University Press, ISBN 0-231-03627-2.

- ^ Hakeda, Yoshito S., transl. (1972). Kukai: Major Works, Translated, With an Account of His Life and a Study of His Thought, p. 79. New York: Columbia University Press, ISBN 0-231-03627-2.

- ^ The Koyasan Shingon-shu Lay Practitioner's Daily Service Archived 2 May 2006 at the Wayback Machine, Shingon Buddhist International Institute (1999)

- ^ Unno, Mark, Shingon Refractions: Myoe and the Mantra of Light, Ch. 1.

- ^ Orzech, Sørensen & Payne 2011, pp. 924–925.

- ^ D. T. Suzuki discusses what he calls "the Shingon elements of Chinese Zen" in his Manual of Zen Buddhism (1960, 21) and "the Chinese Shingon element" in The Training of the Zen Buddhist Monk (1965, 80).

- ^ Griffiths, Paul J. (November 1994). "The Nyingma School of Tibetan Buddhism: Its Fundamentals and History. Dudjom Rinpoche , Gyurme Dorje , Matthew Kapstein". History of Religions. 34 (2): 192–194. doi:10.1086/463389. ISSN 0018-2710.

- ^ Audio |Bon Shen Ling Audio |A Tibetan Bon Education Fund Archived 26 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Boyce, Mary (1996). A History Of Zoroastrianism: The Early Period. Brill. pp. 8–9.

- ^ "AVESTA: KHORDA AVESTA: Part 1". www.avesta.org. Retrieved 16 July 2019.

- ^ Kotwal, Firoze M.; Kreyenbroek, Philip G. (2015). "Chapter 20 - Prayer". In Stausberg, Michael; Vevaina, Yuhan Sohrab-Dinshaw (eds.). The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Zoroastrianism. Wiley Blackwell. p. 335.

- ^ Spiegel, Friedrich (1887). Die arische Periode und ihre Zustände. Verlag von Wilhelm Friedrich. p. 230.

- ^ Bryant, Edwin (2001). The Quest for the Origins of Vedic Culture. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 131.

- ^ jaina.org Archived 16 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ <The Song of the Soul, An Introduction to the Namokar Mantra and the Science of Sound, Acharya Sushil Kumar, Siddhachalam Publishers, 1987.

- ^ <Id., at 23.

- ^ <Chanting with Guruji, Siddhachalam Publishers, 1983.

- ^ Id., at 22.

- ^ Jaini, Padmanabh (2000). Collected Papers on Jaina Studies. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publ. ISBN 81-208-1691-9. p.18 and 224

- ^ Varni, Jinendra; Ed. Prof. Sagarmal Jain, Translated Justice T.K. Tukol and Dr. K.K. Dixit (1993). Samaṇ Suttaṁ. New Delhi: Bhagwan Mahavir memorial Samiti. verse 84

- ^ Jaini, Padmanabh (2000). Collected Papers on Jaina Studies. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publ. ISBN 81-208-1691-9. p. 285

- ^ Chapple. C.K. (2006) Jainism and Ecology: Nonviolence in the Web of Life Delhi:Motilal Banarasidas Publ. ISBN 978-81-208-2045-6 p.46

- ^ Translated from Prakrit by Nagin J. shah and Madhu Sen (1993) Concept of Pratikramana Ahmedabad: Gujarat Vidyapith pp.25–26

- ^ a b Tālib, Gurbachan Siṅgh (1992). "MŪL MANTRA". Encyclopaedia of Sikhism. Patiala: Punjabi University. Archived from the original on 3 September 2011. Retrieved 19 September 2010.

- ^ Gurdas, Bhai. "GUR MANTRA". SikhiTotheMax. Archived from the original on 7 September 2018. Retrieved 9 September 2018.

- ^ Kirkland, Russell (2004). Taoism: The Enduring Tradition. pp. 203-204. Presbyterian Publishing Corp.

- ^ Wong, Eva (1996). Teachings of the Tao, pp. 59-63. Shambhala Publications.

- ^ Yin Shih Tzu (2012). Tranquil Sitting: A Taoist Journal on Meditation and Chinese Medical Qigong, p. 82. Singing Dragon.

- ^ "口遊". S.biglobe.ne.jp. Archived from the original on 14 September 2012. Retrieved 18 July 2012.

- ^ "雪域佛教". Archived from the original on 12 July 2012. Retrieved 17 July 2012.

- ^ "普傳各種本尊神咒". Buddhasun.net. Archived from the original on 15 March 2012. Retrieved 17 July 2012.

- ^ "Mantra – 真佛蓮花小棧(True Buddha Lotus Place)". Lotushouse.weebly.com. 27 February 2010. Archived from the original on 13 March 2012. Retrieved 17 July 2012.

- ^ "An "Emperor" and a "Lord Buddha" of the Yi Guan Dao Are Executed". Chinese Sociology & Anthropology. 21 (4): 35–36. 1989. doi:10.2753/CSA0009-4625210435.

- ^ 第094卷 民国宗教史 Archived 22 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ 《原本大学微言》09、中原文化的精品|南怀瑾 – 劝学网 Archived 29 November 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "畫符念咒:清代民間秘密宗教的符咒療法" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 March 2012. Retrieved 17 July 2012.

- ^ 清代的民间宗教 Archived 19 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "人生守則廿字真言感恩、知足、惜福,天帝教祝福您!". Tienti.info. Archived from the original on 1 March 2012. Retrieved 17 July 2012.

References

- Gelongma Karma Khechong Palmo. Mantras on the Prayer Flag. Kailash: A Journal of Himalayan Studies, Volume 1, Number 2, 1973. (pp. 168–169).

- The Rider Encyclopedia of Eastern Philosophy and religion. (London : Rider, 1986).

- Durgananda, Swami. Meditation Revolution. (Agama Press, 1997). ISBN 0-9654096-0-0

- Vishnu-Devananda, Swami (1981), Meditation and Mantras, Motilal Banarsidass Publishers, ISBN 81-208-1615-3

- Stutley, Margaret; Stutley, James (2002), A Dictionary of Hinduism, Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers, ISBN 81-215-1074-0