Nelson Mandela

Nelson Mandela | |

|---|---|

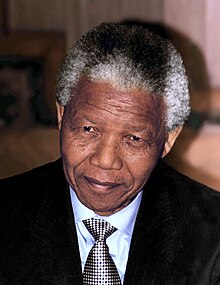

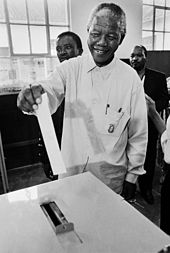

Mandela in October 1994 | |

| 1st President of South Africa | |

| In office 10 May 1994 – 14 June 1999 | |

| Deputy |

|

| Preceded by | Frederik Willem de Klerk (as State President) |

| Succeeded by | Thabo Mbeki |

| 11th President of the African National Congress | |

| In office 7 July 1991 – 20 December 1997 | |

| Deputy |

|

| Preceded by | Oliver Tambo |

| Succeeded by | Thabo Mbeki |

| 2nd and 4th Deputy President of the African National Congress | |

| In office May 1985 – 7 July 1991 | |

| President | Oliver Tambo |

| Preceded by | Oliver Tambo |

| Succeeded by | Walter Sisulu |

| In office December 1952 – 1958 | |

| President | Albert Luthuli |

| Preceded by | Walter Rubusana |

| Succeeded by | Oliver Tambo |

| 19th Secretary-General of the Non-Aligned Movement | |

| In office 2 September 1998 – 14 June 1999 | |

| Preceded by | Andrés Pastrana Arango |

| Succeeded by | Thabo Mbeki |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Rolihlahla Mandela 18 July 1918 Mvezo, South Africa |

| Died | 5 December 2013 (aged 95) Johannesburg, South Africa |

| Resting place | Mandela Graveyard, Qunu, Eastern Cape |

| Political party | African National Congress |

| Other political affiliations | South African Communist Party (Tripartite Alliance) |

| Spouses | |

| Children | 6, including Makgatho, Maki, Zenani, and Zindziswa |

| Alma mater | |

| Occupation |

|

| Known for | Anti-apartheid activism |

| Awards |

|

| Signature |  |

| Website | Foundation |

| Nicknames |

|

| Writing career | |

| Notable works | Long Walk to Freedom |

Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela (/mænˈdɛlə/ man-DEL-ə,[1] Xhosa: [xolíɬaɬa mandɛ̂ːla]; born Rolihlahla Mandela; 18 July 1918 – 5 December 2013) was a South African anti-apartheid activist and politician who served as the first president of South Africa from 1994 to 1999. He was the country's first black head of state and the first elected in a fully representative democratic election. His government focused on dismantling the legacy of apartheid by fostering racial reconciliation. Ideologically an African nationalist and socialist, he served as the president of the African National Congress (ANC) party from 1991 to 1997.

A Xhosa, Mandela was born into the Thembu royal family in Mvezo, South Africa. He studied law at the University of Fort Hare and the University of Witwatersrand before working as a lawyer in Johannesburg. There he became involved in anti-colonial and African nationalist politics, joining the ANC in 1943 and co-founding its Youth League in 1944. After the National Party's white-only government established apartheid, a system of racial segregation that privileged whites, Mandela and the ANC committed themselves to its overthrow. He was appointed president of the ANC's Transvaal branch, rising to prominence for his involvement in the 1952 Defiance Campaign and the 1955 Congress of the People. He was repeatedly arrested for seditious activities and was unsuccessfully prosecuted in the 1956 Treason Trial. Influenced by Marxism, he secretly joined the banned South African Communist Party (SACP). Although initially committed to non-violent protest, in association with the SACP he co-founded the militant uMkhonto we Sizwe in 1961 that led a sabotage campaign against the apartheid government. He was arrested and imprisoned in 1962, and, following the Rivonia Trial, was sentenced to life imprisonment for conspiring to overthrow the state.

Mandela served 27 years in prison, split between Robben Island, Pollsmoor Prison and Victor Verster Prison. Amid growing domestic and international pressure and fears of racial civil war, President F. W. de Klerk released him in 1990. Mandela and de Klerk led efforts to negotiate an end to apartheid, which resulted in the 1994 multiracial general election in which Mandela led the ANC to victory and became president. Leading a broad coalition government which promulgated a new constitution, Mandela emphasised reconciliation between the country's racial groups and created the Truth and Reconciliation Commission to investigate past human rights abuses. Economically, his administration retained its predecessor's liberal framework despite his own socialist beliefs, also introducing measures to encourage land reform, combat poverty and expand healthcare services. Internationally, Mandela acted as mediator in the Pan Am Flight 103 bombing trial and served as secretary-general of the Non-Aligned Movement from 1998 to 1999. He declined a second presidential term and was succeeded by his deputy, Thabo Mbeki. Mandela became an elder statesman and focused on combating poverty and HIV/AIDS through the charitable Nelson Mandela Foundation.

Mandela was a controversial figure for much of his life. Although critics on the right denounced him as a communist terrorist and those on the far left deemed him too eager to negotiate and reconcile with apartheid's supporters, he gained international acclaim for his activism. Globally regarded as an icon of democracy and social justice, he received more than 250 honours, including the Nobel Peace Prize. He is held in deep respect within South Africa, where he is often referred to by his Thembu clan name, Madiba, and described as the "Father of the Nation".

Early life

Childhood: 1918–1934

Mandela was born on 18 July 1918, in the village of Mvezo in Umtata, then part of South Africa's Cape Province.[2] He was given the forename Rolihlahla,[a] a Xhosa term colloquially meaning "troublemaker",[5] and in later years became known by his clan name, Madiba.[6] His patrilineal great-grandfather, Ngubengcuka, was ruler of the Thembu Kingdom in the Transkeian Territories of South Africa's modern Eastern Cape province.[7] One of Ngubengcuka's sons, named Mandela, was Nelson's grandfather and the source of his surname.[8] Because Mandela was the king's child by a wife of the Ixhiba clan, a so-called "Left-Hand House", the descendants of his cadet branch of the royal family were morganatic, ineligible to inherit the throne but recognised as hereditary royal councillors.[9]

Nelson Mandela's father, Gadla Henry Mphakanyiswa Mandela, was a local chief and councillor to the monarch; he was appointed to the position in 1915, after his predecessor was accused of corruption by a governing white magistrate.[10] In 1926, Gadla was also sacked for corruption, but Nelson was told that his father had lost his job for standing up to the magistrate's unreasonable demands.[11] A devotee of the god Qamata,[12] Gadla was a polygamist with four wives, four sons and nine daughters, who lived in different villages. Nelson's mother was Gadla's third wife, Nosekeni Fanny, daughter of Nkedama of the Right Hand House and a member of the amaMpemvu clan of the Xhosa.[13]

No one in my family had ever attended school ... On the first day of school my teacher, Miss Mdingane, gave each of us an English name. This was the custom among Africans in those days and was undoubtedly due to the British bias of our education. That day, Miss Mdingane told me that my new name was Nelson. Why this particular name, I have no idea.

Mandela later stated that his early life was dominated by traditional Xhosa custom and taboo.[15] He grew up with two sisters in his mother's kraal in the village of Qunu, where he tended herds as a cattle-boy and spent much time outside with other boys.[16] Both his parents were illiterate, but his mother, being a devout Christian, sent him to a local Methodist school when he was about seven. Baptised a Methodist, Mandela was given the English forename of "Nelson" by his teacher.[17] When Mandela was about nine, his father came to stay at Qunu, where he died of an undiagnosed ailment that Mandela believed to be lung disease.[18] Feeling "cut adrift", he later said that he inherited his father's "proud rebelliousness" and "stubborn sense of fairness".[19]

Mandela's mother took him to the "Great Place" palace at Mqhekezweni, where he was entrusted to the guardianship of the Thembu regent, Chief Jongintaba Dalindyebo. Although he did not see his mother again for many years, Mandela felt that Jongintaba and his wife Noengland treated him as their own child, raising him alongside their children.[20] As Mandela attended church services every Sunday with his guardians, Christianity became a significant part of his life.[21] He attended a Methodist mission school located next to the palace, where he studied English, Xhosa, history and geography.[22] He developed a love of African history, listening to the tales told by elderly visitors to the palace, and was influenced by the anti-imperialist rhetoric of a visiting chief, Joyi.[23] Nevertheless, at the time he considered the European colonizers not as oppressors but as benefactors who had brought education and other benefits to southern Africa.[24] Aged 16, he, his cousin Justice and several other boys travelled to Tyhalarha to undergo the ulwaluko circumcision ritual that symbolically marked their transition from boys to men; afterwards he was given the name Dalibunga.[25]

Clarkebury, Healdtown, and Fort Hare: 1934–1940

Intending to gain skills needed to become a privy councillor for the Thembu royal house, Mandela began his secondary education in 1933 at Clarkebury Methodist High School in Engcobo, a Western-style institution that was the largest school for black Africans in Thembuland.[26] Made to socialise with other students on an equal basis, he claimed that he lost his "stuck up" attitude, becoming best friends with a girl for the first time; he began playing sports and developed his lifelong love of gardening.[27] He completed his Junior Certificate in two years,[28] and in 1937 he moved to Healdtown, the Methodist college in Fort Beaufort attended by most Thembu royalty, including Justice.[29] The headmaster emphasised the superiority of European culture and government, but Mandela became increasingly interested in native African culture, making his first non-Xhosa friend, a speaker of Sotho, and coming under the influence of one of his favourite teachers, a Xhosa who broke taboo by marrying a Sotho.[30] Mandela spent much of his spare time at Healdtown as a long-distance runner and boxer, and in his second year he became a prefect.[31]

In 1939, with Jongintaba's backing, Mandela began work on a BA degree at the University of Fort Hare, an elite black institution of approximately 150 students in Alice, Eastern Cape. He studied English, anthropology, politics, "native administration", and Roman Dutch law in his first year, desiring to become an interpreter or clerk in the Native Affairs Department.[32] Mandela stayed in the Wesley House dormitory, befriending his own kinsman, K. D. Matanzima, as well as Oliver Tambo, who became a close friend and comrade for decades to come.[33] He took up ballroom dancing,[34] performed in a drama society play about Abraham Lincoln,[35] and gave Bible classes in the local community as part of the Student Christian Association.[36] Although he had friends who held connections to the African National Congress (ANC) who wanted South Africa to be independent of the British Empire, Mandela avoided any involvement with the nascent movement,[37] and became a vocal supporter of the British war effort when the Second World War broke out.[38] At the end of his first year he became involved in a students' representative council (SRC) boycott against the quality of food, for which he was suspended from the university; he never returned to complete his degree.[39]

Arriving in Johannesburg: 1941–1943

Returning to Mqhekezweni in December 1940, Mandela found that Jongintaba had arranged marriages for him and Justice; dismayed, they fled to Johannesburg via Queenstown, arriving in April 1941.[40] Mandela found work as a night watchman at Crown Mines, his "first sight of South African capitalism in action", but was fired when the induna (headman) discovered that he was a runaway.[41] He stayed with a cousin in George Goch Township, who introduced Mandela to realtor and ANC activist Walter Sisulu. The latter secured Mandela a job as an articled clerk at the law firm of Witkin, Sidelsky and Eidelman, a company run by Lazar Sidelsky, a liberal Jew sympathetic to the ANC's cause.[42] At the firm, Mandela befriended Gaur Radebe—a Hlubi member of the ANC and Communist Party—and Nat Bregman, a Jewish communist who became his first white friend.[43] Mandela attended Communist Party gatherings, where he was impressed that Europeans, Africans, Indians, and Coloureds mixed as equals. He later stated that he did not join the party because its atheism conflicted with his Christian faith, and because he saw the South African struggle as being racially based rather than as class warfare.[44] To continue his higher education, Mandela signed up to a University of South Africa correspondence course, working on his bachelor's degree at night.[45]

Earning a small wage, Mandela rented a room in the house of the Xhoma family in the Alexandra township; despite being rife with poverty, crime and pollution, Alexandra always remained a special place for him.[46] Although embarrassed by his poverty, he briefly dated a Swazi woman before unsuccessfully courting his landlord's daughter.[47] To save money and be closer to downtown Johannesburg, Mandela moved into the compound of the Witwatersrand Native Labour Association, living among miners of various tribes; as the compound was visited by various chiefs, he once met the Queen Regent of Basutoland.[48] In late 1941, Jongintaba visited Johannesburg—there forgiving Mandela for running away—before returning to Thembuland, where he died in the winter of 1942.[49] After he passed his BA exams in early 1943, Mandela returned to Johannesburg to follow a political path as a lawyer rather than become a privy councillor in Thembuland.[50]

Early revolutionary activity

Law studies and the ANC Youth League: 1943–1949

Mandela began studying law at the University of the Witwatersrand, where he was the only black African student and faced racism. There, he befriended liberal and communist European, Jewish and Indian students, among them Joe Slovo and Ruth First.[51] Becoming increasingly politicised, Mandela marched in August 1943 in support of a successful bus boycott to reverse fare rises.[52] Joining the ANC, he was increasingly influenced by Sisulu, spending time with other activists at Sisulu's Orlando house, including his old friend Oliver Tambo.[53] In 1943, Mandela met Anton Lembede, an ANC member affiliated with the "Africanist" branch of African nationalism, which was virulently opposed to a racially united front against colonialism and imperialism or to an alliance with the communists.[54] Despite his friendships with non-blacks and communists, Mandela embraced Lembede's views, believing that black Africans should be entirely independent in their struggle for political self-determination.[55] Deciding on the need for a youth wing to mass-mobilise Africans in opposition to their subjugation, Mandela was among a delegation that approached ANC president Alfred Bitini Xuma on the subject at his home in Sophiatown; the African National Congress Youth League (ANCYL) was founded on Easter Sunday 1944 in the Bantu Men's Social Centre, with Lembede as president and Mandela as a member of its executive committee.[56]

At Sisulu's house, Mandela met Evelyn Mase, a trainee nurse and ANC activist from Engcobo, Transkei. Entering a relationship and marrying in October 1944, they initially lived with her relatives until moving into a rented house in the township of Orlando in early 1946.[58] Their first child, Madiba "Thembi" Thembekile, was born in February 1945; a daughter, Makaziwe, was born in 1947 but died of meningitis nine months later.[59] Mandela enjoyed home life, welcoming his mother and his sister, Leabie, to stay with him.[60] In early 1947, his three years of articles ended at Witkin, Sidelsky and Eidelman, and he decided to become a full-time student, subsisting on loans from the Bantu Welfare Trust.[61]

In July 1947, Mandela rushed Lembede, who was ill, to hospital, where he died; he was succeeded as ANCYL president by the more moderate Peter Mda, who agreed to co-operate with communists and non-blacks, appointing Mandela ANCYL secretary.[62] Mandela disagreed with Mda's approach, and in December 1947 supported an unsuccessful measure to expel communists from the ANCYL, considering their ideology un-African.[63] In 1947, Mandela was elected to the executive committee of the ANC's Transvaal Province branch, serving under regional president C. S. Ramohanoe. When Ramohanoe acted against the wishes of the committee by co-operating with Indians and communists, Mandela was one of those who forced his resignation.[64]

In the South African general election in 1948, in which only whites were permitted to vote, the Afrikaner-dominated Herenigde Nasionale Party under Daniel François Malan took power, soon uniting with the Afrikaner Party to form the National Party. Openly racialist, the party codified and expanded racial segregation with new apartheid legislation.[65] Gaining increasing influence in the ANC, Mandela and his party cadre allies began advocating direct action against apartheid, such as boycotts and strikes, influenced by the tactics already employed by South Africa's Indian community. Xuma did not support these measures and was removed from the presidency in a vote of no confidence, replaced by James Moroka and a more militant executive committee containing Sisulu, Mda, Tambo and Godfrey Pitje.[66] Mandela later related that he and his colleagues had "guided the ANC to a more radical and revolutionary path."[67] Having devoted his time to politics, Mandela failed his final year at Witwatersrand three times; he was ultimately denied his degree in December 1949.[68]

Defiance Campaign and Transvaal ANC Presidency: 1950–1954

Mandela took Xuma's place on the ANC national executive in March 1950,[70] and that same year was elected national president of the ANCYL.[71] In March, the Defend Free Speech Convention was held in Johannesburg, bringing together African, Indian and communist activists to call a May Day general strike in protest against apartheid and white minority rule. Mandela opposed the strike because it was multi-racial and not ANC-led, but a majority of black workers took part, resulting in increased police repression and the introduction of the Suppression of Communism Act, 1950, affecting the actions of all protest groups.[72] At the ANC national conference of December 1951, he continued arguing against a racially united front, but was outvoted.[73]

Thereafter, Mandela rejected Lembede's Africanism and embraced the idea of a multi-racial front against apartheid.[74] Influenced by friends like Moses Kotane and by the Soviet Union's support for wars of national liberation, his mistrust of communism broke down and he began reading literature by Karl Marx, Vladimir Lenin, and Mao Zedong, eventually embracing the Marxist philosophy of dialectical materialism.[75] Commenting on communism, he later stated that he "found [himself] strongly drawn to the idea of a classless society which, to [his] mind, was similar to traditional African culture where life was shared and communal."[76] In April 1952, Mandela began work at the H.M. Basner law firm, which was owned by a communist,[77] although his increasing commitment to work and activism meant he spent less time with his family.[78]

In 1952, the ANC began preparation for a joint Defiance Campaign against apartheid with Indian and communist groups, founding a National Voluntary Board to recruit volunteers. The campaign was designed to follow the path of nonviolent resistance influenced by Mahatma Gandhi; some supported this for ethical reasons, but Mandela instead considered it pragmatic.[79] At a Durban rally on 22 June, Mandela addressed an assembled crowd of 10,000 people, initiating the campaign protests for which he was arrested and briefly interned in Marshall Square prison.[80] These events established Mandela as one of the best-known black political figures in South Africa.[81] With further protests, the ANC's membership grew from 20,000 to 100,000 members; the government responded with mass arrests and introduced the Public Safety Act, 1953 to permit martial law.[82] In May, authorities banned Transvaal ANC president J. B. Marks from making public appearances; unable to maintain his position, he recommended Mandela as his successor. Although Africanists opposed his candidacy, Mandela was elected to be regional president in October.[83]

In July 1952, Mandela was arrested under the Suppression of Communism Act and stood trial as one of the 21 accused—among them Moroka, Sisulu and Yusuf Dadoo—in Johannesburg. Found guilty of "statutory communism", a term that the government used to describe most opposition to apartheid, their sentence of nine months' hard labour was suspended for two years.[84] In December, Mandela was given a six-month ban from attending meetings or talking to more than one individual at a time, making his Transvaal ANC presidency impractical, and during this period the Defiance Campaign petered out.[85] In September 1953, Andrew Kunene read out Mandela's "No Easy Walk to Freedom" speech at a Transvaal ANC meeting; the title was taken from a quote by Indian independence leader Jawaharlal Nehru, a seminal influence on Mandela's thought. The speech laid out a contingency plan for a scenario in which the ANC was banned. This Mandela Plan, or M-Plan, involved dividing the organisation into a cell structure with a more centralised leadership.[86]

Mandela obtained work as an attorney for the firm Terblanche and Briggish, before moving to the liberal-run Helman and Michel, passing qualification exams to become a full-fledged attorney.[87] In August 1953, Mandela and Tambo opened their own law firm, Mandela and Tambo, operating in downtown Johannesburg. The only African-run law firm in the country, it was popular with aggrieved black people, often dealing with cases of police brutality. Disliked by the authorities, the firm was forced to relocate to a remote location after their office permit was removed under the Group Areas Act; as a result, their clientele dwindled.[88] As a lawyer of aristocratic heritage, Mandela was part of Johannesburg's elite black middle-class, and accorded much respect from the black community.[89] Although a second daughter, Makaziwe Phumia, was born in May 1954, Mandela's relationship with Evelyn became strained, and she accused him of adultery. He may have had affairs with ANC member Lillian Ngoyi and secretary Ruth Mompati; various individuals close to Mandela in this period have stated that the latter bore him a child.[90] Disgusted by her son's behaviour, Nosekeni returned to Transkei, while Evelyn embraced the Jehovah's Witnesses and rejected Mandela's preoccupation with politics.[91]

Congress of the People and the Treason Trial: 1955–1961

We, the people of South Africa, declare for all our country and the world to know:

That South Africa belongs to all who live in it, black and white, and that no government can justly claim authority unless it is based on the will of the people.

After taking part in the unsuccessful protest to prevent the forced relocation of all black people from the Sophiatown suburb of Johannesburg in February 1955, Mandela concluded that violent action would prove necessary to end apartheid and white minority rule.[93] On his advice, Sisulu requested weaponry from the People's Republic of China, which was denied. Although the Chinese government supported the anti-apartheid struggle, they believed the movement insufficiently prepared for guerrilla warfare.[94] With the involvement of the South African Indian Congress, the Coloured People's Congress, the South African Congress of Trade Unions and the Congress of Democrats, the ANC planned a Congress of the People, calling on all South Africans to send in proposals for a post-apartheid era. Based on the responses, a Freedom Charter was drafted by Rusty Bernstein, calling for the creation of a democratic, non-racialist state with the nationalisation of major industry. The charter was adopted at a June 1955 conference in Kliptown, which was forcibly closed down by police.[95] The tenets of the Freedom Charter remained important for Mandela, and in 1956 he described it as "an inspiration to the people of South Africa".[96]

Following the end of a second ban in September 1955, Mandela went on a working holiday to Transkei to discuss the implications of the Bantu Authorities Act, 1951 with local Xhosa chiefs, also visiting his mother and Noengland before proceeding to Cape Town.[97] In March 1956, he received his third ban on public appearances, restricting him to Johannesburg for five years, but he often defied it.[98] Mandela's marriage broke down and Evelyn left him, taking their children to live with her brother. Initiating divorce proceedings in May 1956, she claimed that Mandela had physically abused her; he denied the allegations and fought for custody of their children.[99] She withdrew her petition of separation in November, but Mandela filed for divorce in January 1958; the divorce was finalised in March, with the children placed in Evelyn's care.[100] During the divorce proceedings, he began courting a social worker, Winnie Madikizela, whom he married in Bizana in June 1958. She later became involved in ANC activities, spending several weeks in prison.[101] Together they had two children: Zenani, born in February 1959, and Zindziswa (1960–2020).[102]

In December 1956, Mandela was arrested alongside most of the ANC national executive and accused of "high treason" against the state. Held in Johannesburg Prison amid mass protests, they underwent a preparatory examination before being granted bail.[103] The defence's refutation began in January 1957, overseen by defence lawyer Vernon Berrangé, and continued until the case was adjourned in September. In January 1958, Oswald Pirow was appointed to prosecute the case, and in February the judge ruled that there was "sufficient reason" for the defendants to go on trial in the Transvaal Supreme Court.[104] The formal Treason Trial began in Pretoria in August 1958, with the defendants successfully applying to have the three judges—all linked to the governing National Party—replaced. In August, one charge was dropped, and in October the prosecution withdrew its indictment, submitting a reformulated version in November which argued that the ANC leadership committed high treason by advocating violent revolution, a charge the defendants denied.[105]

In April 1959, Africanists dissatisfied with the ANC's united front approach founded the Pan-Africanist Congress (PAC); Mandela disagreed with the PAC's racially exclusionary views, describing them as "immature" and "naïve".[106] Both parties took part in an anti-pass campaign in early 1960, in which Africans burned the passes that they were legally obliged to carry. One of the PAC-organised demonstrations was fired upon by police, resulting in the deaths of 69 protesters in the Sharpeville massacre. The incident brought international condemnation of the government and resulted in rioting throughout South Africa, with Mandela publicly burning his pass in solidarity.[107]

Responding to the unrest, the government implemented state of emergency measures, declaring martial law and banning the ANC and PAC; in March, they arrested Mandela and other activists, imprisoning them for five months without charge in the unsanitary conditions of the Pretoria Local prison.[108] Imprisonment caused problems for Mandela and his co-defendants in the Treason Trial; their lawyers could not reach them, and so it was decided that the lawyers would withdraw in protest until the accused were freed from prison when the state of emergency was lifted in late August 1960.[109] Over the following months, Mandela used his free time to organise an All-In African Conference near Pietermaritzburg, Natal, in March 1961, at which 1,400 anti-apartheid delegates met, agreeing on a stay-at-home strike to mark 31 May, the day South Africa became a republic.[110] On 29 March 1961, six years after the Treason Trial began, the judges produced a verdict of not guilty, ruling that there was insufficient evidence to convict the accused of "high treason", since they had advocated neither communism nor violent revolution; the outcome embarrassed the government.[111]

MK, the SACP, and African tour: 1961–62

Disguised as a chauffeur, Mandela travelled around the country incognito, organising the ANC's new cell structure and the planned mass stay-at-home strike. Referred to as the "Black Pimpernel" in the press—a reference to Emma Orczy's 1905 novel The Scarlet Pimpernel—a warrant for his arrest was put out by the police.[112] Mandela held secret meetings with reporters, and after the government failed to prevent the strike, he warned them that many anti-apartheid activists would soon resort to violence through groups like the PAC's Poqo.[113] He believed that the ANC should form an armed group to channel some of this violence in a controlled direction, convincing both ANC leader Albert Luthuli—who was morally opposed to violence—and allied activist groups of its necessity.[114]

Inspired by the actions of Fidel Castro's 26th of July Movement in the Cuban Revolution, in 1961 Mandela, Sisulu and Slovo co-founded Umkhonto we Sizwe ("Spear of the Nation", abbreviated MK). Becoming chairman of the militant group, Mandela gained ideas from literature on guerrilla warfare by Marxist militants Mao and Che Guevara as well as from the military theorist Carl von Clausewitz.[115] Although initially declared officially separate from the ANC so as not to taint the latter's reputation, MK was later widely recognised as the party's armed wing.[116] Most early MK members were white communists who were able to conceal Mandela in their homes; after hiding in communist Wolfie Kodesh's flat in Berea, Mandela moved to the communist-owned Liliesleaf Farm in Rivonia, there joined by Raymond Mhlaba, Slovo and Bernstein, who put together the MK constitution.[117] Although in later life Mandela denied, for political reasons, ever being a member of the Communist Party, historical research published in 2011 strongly suggested that he had joined in the late 1950s or early 1960s.[118] This was confirmed by both the SACP and the ANC after Mandela's death. According to the SACP, he was not only a member of the party, but also served on its Central Committee.[119][120]

We of Umkhonto have always sought to achieve liberation without bloodshed and civil clash. Even at this late hour, we hope that our first actions will awaken everyone to a realization of the dangerous situation to which Nationalist policy is leading. We hope that we will bring the Government and its supporters to their senses before it is too late so that both government and its policies can be changed before matters reach the desperate stage of civil war.

Operating through a cell structure, MK planned to carry out acts of sabotage that would exert maximum pressure on the government with minimum casualties; they sought to bomb military installations, power plants, telephone lines, and transport links at night, when civilians were not present. Mandela stated that they chose sabotage because it was the least harmful action, did not involve killing, and offered the best hope for racial reconciliation afterwards; he nevertheless acknowledged that should this have failed then guerrilla warfare might have been necessary.[122] Soon after ANC leader Luthuli was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, MK publicly announced its existence with 57 bombings on Dingane's Day (16 December) 1961, followed by further attacks on New Year's Eve.[123]

The ANC decided to send Mandela as a delegate to the February 1962 meeting of the Pan-African Freedom Movement for East, Central and Southern Africa (PAFMECSA) in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.[124] Leaving South Africa in secret via Bechuanaland, on his way Mandela visited Tanganyika and met with its president, Julius Nyerere.[125] Arriving in Ethiopia, Mandela met with Emperor Haile Selassie I, and gave his speech after Selassie's at the conference.[126] After the symposium, he travelled to Cairo, Egypt, admiring the political reforms of President Gamal Abdel Nasser, and in April 1962 he went to Morocco where asked El Khatib to meet the king to ask him to give him £5,000. The next day he got the £5,000 along with some weapons and training to Mandela's soldier, and then went to Tunis, Tunisia, where President Habib Bourguiba gave him £5,000 for weaponry. He proceeded to Morocco, Mali, Guinea, Sierra Leone, Liberia and Senegal, receiving funds from Liberian president William Tubman and Guinean president Ahmed Sékou Touré.[127] He left Africa for London, England, where he met anti-apartheid activists, reporters and prominent politicians.[128] Upon returning to Ethiopia, he began a six-month course in guerrilla warfare, but completed only two months before being recalled to South Africa by the ANC's leadership.[129]

Imprisonment

Arrest and Rivonia trial: 1962–1964

On 5 August 1962, police captured Mandela along with fellow activist Cecil Williams near Howick.[130] Many MK members suspected that the authorities had been tipped off with regard to Mandela's whereabouts, although Mandela himself gave these ideas little credence.[131] In later years, Donald Rickard, a former American diplomat, revealed that the Central Intelligence Agency, which feared Mandela's associations with communists, had informed the South African police of his location.[132][133] Jailed in Johannesburg's Marshall Square prison, Mandela was charged with inciting workers' strikes and leaving the country without permission. Representing himself with Slovo as legal advisor, Mandela intended to use the trial to showcase "the ANC's moral opposition to racism" while supporters demonstrated outside the court.[134] Moved to Pretoria, where Winnie could visit him, he began correspondence studies for a Bachelor of Laws (LLB) degree from the University of London International Programmes.[135] His hearing began in October, but he disrupted proceedings by wearing a traditional kaross, refusing to call any witnesses, and turning his plea of mitigation into a political speech. Found guilty, he was sentenced to five years' imprisonment; as he left the courtroom, supporters sang "Nkosi Sikelel iAfrika".[136]

I have fought against white domination, and I have fought against black domination. I have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society in which all persons will live together in harmony and with equal opportunities. It is an ideal which I hope to live for and to see realised. But if it needs be, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die.

On 11 July 1963, police raided Liliesleaf Farm, arresting those that they found there and uncovering paperwork documenting MK's activities, some of which mentioned Mandela. The Rivonia Trial began at Pretoria Supreme Court in October, with Mandela and his comrades charged with four counts of sabotage and conspiracy to violently overthrow the government; their chief prosecutor was Percy Yutar.[139] Judge Quartus de Wet soon threw out the prosecution's case for insufficient evidence, but Yutar reformulated the charges, presenting his new case from December 1963 until February 1964, calling 173 witnesses and bringing thousands of documents and photographs to the trial.[140]

Although four of the accused denied involvement with MK, Mandela and the other five accused admitted sabotage but denied that they had ever agreed to initiate guerrilla war against the government.[141] They used the trial to highlight their political cause; at the opening of the defence's proceedings, Mandela gave his three-hour "I Am Prepared to Die" speech. That speech—which was inspired by Castro's "History Will Absolve Me"—was widely reported in the press despite official censorship.[142] The trial gained international attention; there were global calls for the release of the accused from the United Nations and World Peace Council, while the University of London Union voted Mandela to its presidency.[143] On 12 June 1964, justice De Wet found Mandela and two of his co-accused guilty on all four charges; although the prosecution had called for the death sentence to be applied, the judge instead condemned them to life imprisonment.[144]

Robben Island: 1964–1982

In 1964, Mandela and his co-accused were transferred from Pretoria to the prison on Robben Island, remaining there for the next 18 years.[145] Isolated from non-political prisoners in Section B, Mandela was imprisoned in a damp concrete cell measuring 8 feet (2.4 m) by 7 feet (2.1 m), with a straw mat on which to sleep.[146] Verbally and physically harassed by several white prison wardens, the Rivonia Trial prisoners spent their days breaking rocks into gravel, until being reassigned in January 1965 to work in a lime quarry. Mandela was initially forbidden to wear sunglasses, and the glare from the lime permanently damaged his eyesight.[147] At night, he worked on his LLB degree, which he was obtaining from the University of London through a correspondence course with Wolsey Hall, Oxford, but newspapers were forbidden, and he was locked in solitary confinement on several occasions for the possession of smuggled news clippings.[148] He was initially classified as the lowest grade of prisoner, Class D, meaning that he was permitted one visit and one letter every six months, although all mail was heavily censored.[149]

The political prisoners took part in work and hunger strikes—the latter considered largely ineffective by Mandela—to improve prison conditions, viewing this as a microcosm of the anti-apartheid struggle.[150] ANC prisoners elected him to their four-man "High Organ" along with Sisulu, Govan Mbeki and Raymond Mhlaba, and he involved himself in a group, named Ulundi, that represented all political prisoners (including Eddie Daniels) on the island, through which he forged links with PAC and Yu Chi Chan Club members.[151] Initiating the "University of Robben Island", whereby prisoners lectured on their own areas of expertise, he debated socio-political topics with his comrades.[152]

Though attending Christian Sunday services, Mandela studied Islam.[153] He also studied Afrikaans, hoping to build a mutual respect with the warders and convert them to his cause.[154] Various official visitors met with Mandela, most significantly the liberal parliamentary representative Helen Suzman of the Progressive Party, who championed Mandela's cause outside of prison.[155] In September 1970, he met British Labour Party politician Denis Healey.[156] South African Minister of Justice Jimmy Kruger visited in December 1974, but he and Mandela did not get along with each other.[157] His mother visited in 1968, dying shortly after, and his firstborn son Thembi died in a car accident the following year; Mandela was forbidden from attending either funeral.[158] His wife was rarely able to see him, being regularly imprisoned for political activity, and his daughters first visited in December 1975. Winnie was released from prison in 1977 but was forcibly settled in Brandfort and remained unable to see him.[159]

From 1967 onwards, prison conditions improved. Black prisoners were given trousers rather than shorts, games were permitted, and the standard of their food was raised.[160] In 1969, an escape plan for Mandela was developed by Gordon Bruce, but it was abandoned after the conspiracy was infiltrated by an agent of the South African Bureau of State Security (BOSS), who hoped to see Mandela shot during the escape.[161] In 1970, Commander Piet Badenhorst became commanding officer. Mandela, seeing an increase in the physical and mental abuse of prisoners, complained to visiting judges, who had Badenhorst reassigned.[162] He was replaced by Commander Willie Willemse, who developed a co-operative relationship with Mandela and was keen to improve prison standards.[163]

By 1975, Mandela had become a Class A prisoner,[165] which allowed him greater numbers of visits and letters. He corresponded with anti-apartheid activists like Mangosuthu Buthelezi and Desmond Tutu.[166] That year, he began his autobiography, which was smuggled to London, but remained unpublished at the time; prison authorities discovered several pages, and his LLB study privileges were revoked for four years.[167] Instead, he devoted his spare time to gardening and reading until the authorities permitted him to resume his LLB degree studies in 1980.[168]

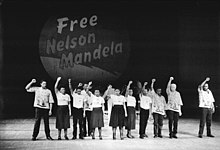

By the late 1960s, Mandela's fame had been eclipsed by Steve Biko and the Black Consciousness Movement (BCM). Seeing the ANC as ineffectual, the BCM called for militant action, but, following the Soweto uprising of 1976, many BCM activists were imprisoned on Robben Island.[169] Mandela tried to build a relationship with these young radicals, although he was critical of their racialism and contempt for white anti-apartheid activists.[170] Renewed international interest in his plight came in July 1978, when he celebrated his 60th birthday.[171] He was awarded an honorary doctorate in Lesotho, the Jawaharlal Nehru Award for International Understanding in India in 1979, and the Freedom of the City of Glasgow, Scotland in 1981.[172] In March 1980, the slogan "Free Mandela!" was developed by journalist Percy Qoboza, sparking an international campaign that led the UN Security Council to call for his release.[173] Despite increasing foreign pressure, the government refused, relying on its Cold War allies US president Ronald Reagan and British prime minister Margaret Thatcher; both considered Mandela's ANC a terrorist organisation sympathetic to communism and supported its suppression.[174]

Pollsmoor Prison: 1982–1988

In April 1982, Mandela was transferred to Pollsmoor Prison in Tokai, Cape Town, along with senior ANC leaders Walter Sisulu, Andrew Mlangeni, Ahmed Kathrada and Raymond Mhlaba; they believed that they were being isolated to remove their influence on younger activists at Robben Island.[175] Conditions at Pollsmoor were better than at Robben Island, although Mandela missed the camaraderie and scenery of the island.[176] Getting on well with Pollsmoor's commanding officer, Brigadier Munro, Mandela was permitted to create a roof garden;[177] he also read voraciously and corresponded widely, now being permitted 52 letters a year.[178] He was appointed patron of the multi-racial United Democratic Front (UDF), founded to combat reforms implemented by South African president P. W. Botha. Botha's National Party government had permitted Coloured and Indian citizens to vote for their own parliaments, which had control over education, health and housing, but black Africans were excluded from the system. Like Mandela, the UDF saw this as an attempt to divide the anti-apartheid movement on racial lines.[179]

The early 1980s witnessed an escalation of violence across the country, and many predicted civil war. This was accompanied by economic stagnation as various multinational banks—under pressure from an international lobby—had stopped investing in South Africa. Numerous banks and Thatcher asked Botha to release Mandela—then at the height of his international fame—to defuse the volatile situation.[180] Although considering Mandela a dangerous "arch-Marxist",[181] Botha offered him, in February 1985, a release from prison if he "unconditionally rejected violence as a political weapon". Mandela spurned the offer, releasing a statement through his daughter Zindzi stating, "What freedom am I being offered while the organisation of the people [ANC] remains banned? Only free men can negotiate. A prisoner cannot enter into contracts."[182][183]

In 1985, Mandela underwent surgery on an enlarged prostate gland before being given new solitary quarters on the ground floor.[184] He was met by an international delegation sent to negotiate a settlement, but Botha's government refused to co-operate, calling a state of emergency in June and initiating a police crackdown on unrest.[185] The anti-apartheid resistance fought back, with the ANC committing 231 attacks in 1986 and 235 in 1987.[186] The violence escalated as the government used the army and police to combat the resistance and provided covert support for vigilante groups and the Zulu nationalist movement Inkatha, which was involved in an increasingly violent struggle with the ANC.[187] Mandela requested talks with Botha but was denied, instead secretly meeting with Minister of Justice Kobie Coetsee in 1987, and having a further 11 meetings over the next three years. Coetsee organised negotiations between Mandela and a team of four government figures starting in May 1988; the team agreed to the release of political prisoners and the legalisation of the ANC on the condition that they permanently renounce violence, break links with the Communist Party, and not insist on majority rule. Mandela rejected these conditions, insisting that the ANC would end its armed activities only when the government renounced violence.[188]

Mandela's 70th birthday in July 1988 attracted international attention, including a tribute concert at London's Wembley Stadium that was televised and watched by an estimated 200 million viewers.[189] Although presented globally as a heroic figure, he faced personal problems when ANC leaders informed him that Winnie had set herself up as head of a gang, the "Mandela United Football Club", which had been responsible for torturing and killing opponents—including children—in Soweto. Though some encouraged him to divorce her, he decided to remain loyal until she was found guilty by trial.[190]

Victor Verster Prison and release: 1988–1990

Recovering from tuberculosis exacerbated by the damp conditions in his cell,[191] Mandela was moved to Victor Verster Prison, near Paarl, in December 1988. He was housed in the relative comfort of a warder's house with a personal cook, and he used the time to complete his LLB degree.[192] While there, he was permitted many visitors and organised secret communications with exiled ANC leader Oliver Tambo.[193][194]

In 1989, Botha suffered a stroke; although he retained the state presidency, he stepped down as leader of the National Party, to be replaced by F. W. de Klerk.[195] In a surprise move, Botha invited Mandela to a meeting over tea in July 1989, an invitation Mandela considered genial.[196] Botha was replaced as state president by de Klerk six weeks later; the new president believed that apartheid was unsustainable and released a number of ANC prisoners.[197] Following the fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989, de Klerk called his cabinet together to debate legalising the ANC and freeing Mandela. Although some were deeply opposed to his plans, de Klerk met with Mandela in December to discuss the situation, a meeting both men considered friendly, before legalising all formerly banned political parties in February 1990 and announcing Mandela's unconditional release.[198][199] Shortly thereafter, for the first time in 20 years, photographs of Mandela were allowed to be published in South Africa.[200]

Leaving Victor Verster Prison on 11 February, Mandela held Winnie's hand in front of amassed crowds and the press; the event was broadcast live across the world.[201][202] Driven to Cape Town's City Hall through crowds, he gave a speech declaring his commitment to peace and reconciliation with the white minority, but he made it clear that the ANC's armed struggle was not over and would continue as "a purely defensive action against the violence of apartheid". He expressed hope that the government would agree to negotiations, so that "there may no longer be the need for the armed struggle", and insisted that his main focus was to bring peace to the black majority and give them the right to vote in national and local elections.[203][204] Staying at Tutu's home, in the following days Mandela met with friends, activists, and press, giving a speech to an estimated 100,000 people at Johannesburg's FNB Stadium.[205]

End of apartheid and elections

Early negotiations: 1990–91

Mandela proceeded on an African tour, meeting supporters and politicians in Zambia, Zimbabwe, Namibia, Libya and Algeria, and continuing to Sweden, where he was reunited with Tambo, and London, where he appeared at the Nelson Mandela: An International Tribute for a Free South Africa concert at Wembley Stadium.[206] Encouraging foreign countries to support sanctions against the apartheid government, he met President François Mitterrand in France, Pope John Paul II in the Vatican, and Thatcher in the United Kingdom. In the United States, he met President George H. W. Bush, addressed both Houses of Congress and visited eight cities, being particularly popular among the African American community.[207] In Cuba, he became friends with President Castro, whom he had long admired.[208] He met President R. Venkataraman in India, President Suharto in Indonesia, Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad in Malaysia, and Prime Minister Bob Hawke in Australia. He visited Japan, but not the Soviet Union, a longtime ANC supporter.[209]

In May 1990, Mandela led a multiracial ANC delegation into preliminary negotiations with a government delegation of 11 Afrikaner men. Mandela impressed them with his discussions of Afrikaner history, and the negotiations led to the Groot Schuur Minute, in which the government lifted the state of emergency.[210] In August, Mandela—recognising the ANC's severe military disadvantage—offered a ceasefire, the Pretoria Minute, for which he was widely criticised by MK activists.[210] He spent much time trying to unify and build the ANC, appearing at a Johannesburg conference in December attended by 1,600 delegates, many of whom found him more moderate than expected.[211] At the ANC's July 1991 national conference in Durban, Mandela admitted that the party had faults and wanted to build a task force for securing majority rule.[212] At the conference, he was elected ANC President, replacing the ailing Tambo, and a 50-strong multiracial, mixed gendered national executive was elected.[212]

Mandela was given an office in the newly purchased ANC headquarters at Shell House, Johannesburg, and moved into Winnie's large Soweto home.[213] Their marriage was increasingly strained as he learned of her affair with Dali Mpofu, but he supported her during her trial for kidnapping and assault. He gained funding for her defence from the International Defence and Aid Fund for Southern Africa and from Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi, but, in June 1991, she was found guilty and sentenced to six years in prison, reduced to two on appeal. On 13 April 1992, Mandela publicly announced his separation from Winnie. The ANC forced her to step down from the national executive for misappropriating ANC funds; Mandela moved into the mostly white Johannesburg suburb of Houghton.[214] Mandela's prospects for a peaceful transition were further damaged by an increase in "black-on-black" violence, particularly between ANC and Inkatha supporters in KwaZulu-Natal, which resulted in thousands of deaths. Mandela met with Inkatha leader Buthelezi, but the ANC prevented further negotiations on the issue. Mandela argued that there was a "third force" within the state intelligence services fuelling the "slaughter of the people" and openly blamed de Klerk—whom he increasingly distrusted—for the Sebokeng massacre.[215] In September 1991, a national peace conference was held in Johannesburg at which Mandela, Buthelezi and de Klerk signed a peace accord, though the violence continued.[216]

CODESA talks: 1991–92

The Convention for a Democratic South Africa (CODESA) began in December 1991 at the Johannesburg World Trade Centre, attended by 228 delegates from 19 political parties. Although Cyril Ramaphosa led the ANC's delegation, Mandela remained a key figure. After de Klerk used the closing speech to condemn the ANC's violence, Mandela took to the stage to denounce de Klerk as the "head of an illegitimate, discredited minority regime". Dominated by the National Party and ANC, little negotiation was achieved.[217] CODESA 2 was held in May 1992, at which de Klerk insisted that post-apartheid South Africa must use a federal system with a rotating presidency to ensure the protection of ethnic minorities; Mandela opposed this, demanding a unitary system governed by majority rule.[218] Following the Boipatong massacre of ANC activists by government-aided Inkatha militants, Mandela called off the negotiations, before attending a meeting of the Organisation of African Unity in Senegal, at which he called for a special session of the UN Security Council and proposed that a UN peacekeeping force be stationed in South Africa to prevent "state terrorism".[219] Calling for domestic mass action, in August the ANC organised the largest-ever strike in South African history, and supporters marched on Pretoria.[220]

Following the Bisho massacre, in which 28 ANC supporters and one soldier were shot dead by the Ciskei Defence Force during a protest march, Mandela realised that mass action was leading to further violence and resumed negotiations in September. He agreed to do so on the conditions that all political prisoners be released, that Zulu traditional weapons be banned, and that Zulu hostels would be fenced off; de Klerk reluctantly agreed.[221] The negotiations agreed that a multiracial general election would be held, resulting in a five-year coalition government of national unity and a constitutional assembly that gave the National Party continuing influence. The ANC also conceded to safeguarding the jobs of white civil servants; such concessions brought fierce internal criticism.[222] The duo agreed on an interim constitution based on a liberal democratic model, guaranteeing separation of powers, creating a constitutional court, and including a US-style bill of rights; it also divided the country into nine provinces, each with its own premier and civil service, a concession between de Klerk's desire for federalism and Mandela's for unitary government.[223]

The democratic process was threatened by the Concerned South Africans Group (COSAG), an alliance of black ethnic-secessionist groups like Inkatha and far-right Afrikaner parties; in June 1993, one of the latter—the Afrikaner Weerstandsbeweging (AWB)—attacked the Kempton Park World Trade Centre.[224] Following the murder of ANC activist Chris Hani, Mandela made a publicised speech to calm rioting, soon after appearing at a mass funeral in Soweto for Tambo, who had died of a stroke.[225] In July 1993, both Mandela and de Klerk visited the United States, independently meeting President Bill Clinton, and each receiving the Liberty Medal.[226] Soon after, Mandela and de Klerk were jointly awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in Norway.[227] Influenced by Thabo Mbeki, Mandela began meeting with big business figures, and he played down his support for nationalisation, fearing that he would scare away much-needed foreign investment. Although criticised by socialist ANC members, he had been encouraged to embrace private enterprise by members of the Chinese and Vietnamese Communist parties at the January 1992 World Economic Forum in Switzerland.[228]

General election: 1994

With the election set for 27 April 1994, the ANC began campaigning, opening 100 election offices and orchestrating People's Forums across the country at which Mandela could appear, as a popular figure with great status among black South Africans.[229] The ANC campaigned on a Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP) to build a million houses in five years, introduce universal free education and extend access to water and electricity. The party's slogan was "a better life for all", although it was not explained how this development would be funded.[230] With the exception of the Weekly Mail and the New Nation, South Africa's press opposed Mandela's election, fearing continued ethnic strife, instead supporting the National or Democratic Party.[231] Mandela devoted much time to fundraising for the ANC, touring North America, Europe and Asia to meet wealthy donors, including former supporters of the apartheid regime.[232] He also urged a reduction in the voting age from 18 to 14; rejected by the ANC, this policy became the subject of ridicule.[233]

Concerned that COSAG would undermine the election, particularly in the wake of the conflict in Bophuthatswana and the Shell House massacre—incidents of violence involving the AWB and Inkatha, respectively—Mandela met with Afrikaner politicians and generals, including P. W. Botha, Pik Botha and Constand Viljoen, persuading many to work within the democratic system. With de Klerk, he also convinced Inkatha's Buthelezi to enter the elections rather than launch a war of secession.[234] As leaders of the two major parties, de Klerk and Mandela appeared on a televised debate; Mandela's offer to shake his hand surprised him, leading some commentators to deem it a victory for Mandela.[235] The election went ahead with little violence, although an AWB cell killed 20 with car bombs. As widely expected, the ANC won a sweeping victory, taking 63% of the vote, just short of the two-thirds majority needed to unilaterally change the constitution. The ANC was also victorious in seven provinces, with Inkatha and the National Party each taking one.[236][237] Mandela voted at the Ohlange High School in Durban, and though the ANC's victory assured his election as president, he publicly accepted that the election had been marred by instances of fraud and sabotage.[238]

Presidency of South Africa: 1994–1999

The newly elected National Assembly's first act was to formally elect Mandela as South Africa's first black chief executive. His inauguration took place in Pretoria on 10 May 1994, televised to a billion viewers globally. The event was attended by four thousand guests, including world leaders from a wide range of geographic and ideological backgrounds.[239] Mandela headed a Government of National Unity dominated by the ANC—which had no experience of governing by itself—but containing representatives from the National Party and Inkatha. Under the Interim Constitution, Inkatha and the National Party were entitled to seats in the government by virtue of winning at least 20 seats. In keeping with earlier agreements, both de Klerk and Thabo Mbeki were given the position of Deputy President.[240][241] Although Mbeki had not been his first choice for the job, Mandela grew to rely heavily on him throughout his presidency, allowing him to shape policy details.[242] Moving into the presidential office at Tuynhuys in Cape Town, Mandela allowed de Klerk to retain the presidential residence in the Groote Schuur estate, instead settling into the nearby Westbrooke manor, which he renamed "Genadendal", meaning "Valley of Mercy" in Afrikaans.[243] Retaining his Houghton home, he also had a house built in his home village of Qunu, which he visited regularly, meeting with locals, and judging tribal disputes.[244]

Aged 76, he faced various ailments, and although exhibiting continued energy, he felt isolated and lonely.[245] He often entertained celebrities, such as Michael Jackson, Whoopi Goldberg and the Spice Girls, and befriended ultra-rich businessmen, like Harry Oppenheimer of Anglo American. He also met with Queen Elizabeth II on her March 1995 state visit to South Africa, which earned him strong criticism from ANC anti-capitalists.[246] Despite his opulent surroundings, Mandela lived simply, donating a third of his R 552,000 annual income to the Nelson Mandela Children's Fund, which he had founded in 1995.[247] Although dismantling press censorship, speaking out in favour of freedom of the press and befriending many journalists, Mandela was critical of much of the country's media, noting that it was overwhelmingly owned and run by middle-class whites and believing that it focused too heavily on scaremongering about crime.[248]

In December 1994, Mandela published Long Walk to Freedom, an autobiography based around a manuscript he had written in prison, augmented by interviews conducted with American journalist Richard Stengel.[249] In late 1994, he attended the 49th conference of the ANC in Bloemfontein, at which a more militant national executive was elected, among them Winnie Mandela; although she expressed an interest in reconciling, Nelson initiated divorce proceedings in August 1995.[250] By 1995, he had entered into a relationship with Graça Machel, a Mozambican political activist 27 years his junior who was the widow of former president Samora Machel. They had first met in July 1990 when she was still in mourning, but their friendship grew into a partnership, with Machel accompanying him on many of his foreign visits. She turned down Mandela's first marriage proposal, wanting to retain some independence and dividing her time between Mozambique and Johannesburg.[251]

National reconciliation

Gracious but steely, [Mandela] steered a country in turmoil toward a negotiated settlement: a country that days before its first democratic election remained violent, riven by divisive views and personalities. He endorsed national reconciliation, an idea he did not merely foster in the abstract, but performed with panache and conviction in reaching out to former adversaries. He initiated an era of hope that, while not long-lasting, was nevertheless decisive, and he garnered the highest international recognition and affection.

Presiding over the transition from apartheid minority rule to a multicultural democracy, Mandela saw national reconciliation as the primary task of his presidency.[253] Having seen other post-colonial African economies damaged by the departure of white elites, Mandela worked to reassure South Africa's white population that they were protected and represented in "the Rainbow Nation".[254] Although his Government of National Unity would be dominated by the ANC,[255] he attempted to create a broad coalition by appointing de Klerk as Deputy President and appointing other National Party officials as ministers for Agriculture, Environment, and Minerals and Energy, as well as naming Buthelezi as Minister for Home Affairs.[256] The other cabinet positions were taken by ANC members, many of whom—like Joe Modise, Alfred Nzo, Joe Slovo, Mac Maharaj and Dullah Omar—had long been comrades of Mandela, although others, such as Tito Mboweni and Jeff Radebe, were far younger.[257] Mandela's relationship with de Klerk was strained; Mandela thought that de Klerk was intentionally provocative, and de Klerk felt that he was being intentionally humiliated by the president.[258] In January 1995, Mandela heavily chastised de Klerk for awarding amnesty to 3,500 police officers just before the election, and later criticised him for defending former Minister of Defence Magnus Malan when the latter was charged with murder.[258]

Mandela personally met with senior figures of the apartheid regime, including lawyer Percy Yutar and Hendrik Verwoerd's widow, Betsie Schoombie, also laying a wreath by the statue of Afrikaner hero Daniel Theron.[259] Emphasising personal forgiveness and reconciliation, he announced that "courageous people do not fear forgiving, for the sake of peace."[260] He encouraged black South Africans to get behind the previously hated national rugby team, the Springboks, as South Africa hosted the 1995 Rugby World Cup. Mandela wore a Springbok shirt at the final against New Zealand, and after the Springboks won the match, Mandela presented the trophy to captain Francois Pienaar, an Afrikaner. This was widely seen as a major step in the reconciliation of white and black South Africans; as de Klerk later put it, "Mandela won the hearts of millions of white rugby fans."[261][262] Mandela's efforts at reconciliation assuaged the fears of white people, but also drew criticism from more militant black people.[263] Among the latter was his estranged wife, Winnie, who accused the ANC of being more interested in appeasing the white community than in helping the black majority.[264]

Mandela oversaw the formation of a Truth and Reconciliation Commission to investigate crimes committed under apartheid by both the government and the ANC, appointing Tutu as its chair. To prevent the creation of martyrs, the commission granted individual amnesties in exchange for testimony of crimes committed during the apartheid era. Dedicated in February 1996, it held two years of hearings detailing rapes, torture, bombings and assassinations before issuing its final report in October 1998. Both de Klerk and Mbeki appealed to have parts of the report suppressed, though only de Klerk's appeal was successful.[265] Mandela praised the commission's work, stating that it "had helped us move away from the past to concentrate on the present and the future".[266]

Domestic programmes

Mandela's administration inherited a country with a huge disparity in wealth and services between white and black communities. Of a population of 40 million, around 23 million lacked electricity or adequate sanitation, and 12 million lacked clean water supplies, with 2 million children not in school and a third of the population illiterate. There was 33% unemployment, and just under half of the population lived below the poverty line.[267] Government financial reserves were nearly depleted, with a fifth of the national budget being spent on debt repayment, meaning that the extent of the promised Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP) was scaled back, with none of the proposed nationalisation or job creation.[268] In 1996, the RDP was replaced with a new policy, Growth, Employment and Redistribution (GEAR), which maintained South Africa's mixed economy but placed an emphasis on economic growth through a framework of market economics and the encouragement of foreign investment; many in the ANC derided it as a neo-liberal policy that did not address social inequality, no matter how Mandela defended it.[269] In adopting this approach, Mandela's government adhered to the "Washington consensus" advocated by the World Bank and International Monetary Fund.[270]

Under Mandela's presidency, welfare spending increased by 13% in 1996/97, 13% in 1997/98, and 7% in 1998/99.[271] The government introduced parity in grants for communities, including disability grants, child maintenance grants and old-age pensions, which had previously been set at different levels for South Africa's different racial groups.[271] In 1994, free healthcare was introduced for children under six and pregnant women, a provision extended to all those using primary level public sector health care services in 1996.[272][273] By the 1999 election, the ANC could boast that due to their policies, 3 million people were connected to telephone lines, 1.5 million children were brought into the education system, 500 clinics were upgraded or constructed, 2 million people were connected to the electricity grid, water access was extended to 3 million people, and 750,000 houses were constructed, housing nearly 3 million people.[274]

The Land Reform Act 3 of 1996 safeguarded the rights of labour tenants living on farms where they grew crops or grazed livestock. This legislation ensured that such tenants could not be evicted without a court order or if they were over the age of 65.[275] Recognising that arms manufacturing was a key industry for the South African economy, Mandela endorsed the trade in weapons but brought in tighter regulations surrounding Armscor to ensure that South African weaponry was not sold to authoritarian regimes.[276] Under Mandela's administration, tourism was increasingly promoted, becoming a major sector of the South African economy.[277]

Critics like Edwin Cameron accused Mandela's government of doing little to stem the HIV/AIDS pandemic in the country; by 1999, 10% of South Africa's population were HIV positive. Mandela later admitted that he had personally neglected the issue, in part due to public reticence in discussing issues surrounding sex in South Africa, and that he had instead left the issue for Mbeki to deal with.[278][279] Mandela also received criticism for failing to sufficiently combat crime; South Africa had one of the world's highest crime rates,[280] and the activities of international crime syndicates in the country grew significantly throughout the decade.[281] Mandela's administration was also perceived as having failed to deal with the problem of corruption.[282]

Further problems were caused by the exodus of thousands of skilled white South Africans from the country, who were escaping the increasing crime rates, higher taxes and the impact of positive discrimination toward black people in employment. This exodus resulted in a brain drain, and Mandela criticised those who left.[283] At the same time, South Africa experienced an influx of millions of illegal migrants from poorer parts of Africa; although public opinion toward these illegal immigrants was generally unfavourable, characterising them as disease-spreading criminals who were a drain on resources, Mandela called on South Africans to embrace them as "brothers and sisters".[284]

Foreign affairs

Mandela expressed the view that "South Africa's future foreign relations [should] be based on our belief that human rights should be the core of international relations".[285] Following the South African example, Mandela encouraged other nations to resolve conflicts through diplomacy and reconciliation.[286] In September 1998, Mandela was appointed secretary-general of the Non-Aligned Movement, who held their annual conference in Durban. He used the event to criticise the "narrow, chauvinistic interests" of the Israeli government in stalling negotiations to end the Israeli–Palestinian conflict and urged India and Pakistan to negotiate to end the Kashmir conflict, for which he was criticised by both Israel and India.[287] Inspired by the region's economic boom, Mandela sought greater economic relations with East Asia, in particular with Malaysia, although this was prevented by the 1997 Asian financial crisis.[288] He extended diplomatic recognition to the People's Republic of China (PRC), who were growing as an economic force, and initially also to Taiwan, who were already longstanding investors in the South African economy. However, under pressure from the PRC, he cut recognition of Taiwan in November 1996, and he paid an official visit to Beijing in May 1999.[289]

Mandela attracted controversy for his close relationship with Indonesian president Suharto, whose regime was responsible for mass human rights abuses, although on a July 1997 visit to Indonesia he privately urged Suharto to withdraw from the occupation of East Timor.[291] He also faced similar criticism from the West for his government's trade links to Syria, Cuba and Libya[292] and for his personal friendships with Castro and Gaddafi.[293] Castro visited South Africa in 1998 to widespread popular acclaim, and Mandela met Gaddafi in Libya to award him the Order of Good Hope.[293] When Western governments and media criticised these visits, Mandela lambasted such criticism as having racist undertones,[294] and stated that "the enemies of countries in the West are not our enemies."[292] Mandela hoped to resolve the long-running dispute between Libya and the United States and Britain over bringing to trial the two Libyans, Abdelbaset al-Megrahi and Lamin Khalifah Fhimah, who were indicted in November 1991 and accused of sabotaging Pan Am Flight 103. Mandela proposed that they be tried in a third country, which was agreed to by all parties; governed by Scots law, the trial was held at Camp Zeist in the Netherlands in April 1999, and found one of the two men guilty.[295][296]

Mandela echoed Mbeki's calls for an "African Renaissance", and he was greatly concerned with issues on the continent.[297] He took a soft diplomatic approach to removing Sani Abacha's military junta in Nigeria but later became a leading figure in calling for sanctions when Abacha's regime increased human rights violations.[298] In 1996, he was appointed chairman of the Southern African Development Community (SADC) and initiated unsuccessful negotiations to end the First Congo War in Zaire.[299] He also played a key role as a mediator in the ethnic conflict between Tutsi and Hutu political groups in the Burundian Civil War, helping to initiate a settlement which brought increased stability to the country but did not end the ethnic violence.[300] In South Africa's first post-apartheid military operation, troops were ordered into Lesotho in September 1998 to protect the government of Prime Minister Pakalitha Mosisili after a disputed election had prompted opposition uprisings. The action was not authorised by Mandela himself, who was out of the country at the time, but by Buthelezi, who was serving as acting president during Mandela's absence,[301] with the approval of Mandela and Mbeki.[302]

Withdrawing from politics

The new Constitution of South Africa was agreed upon by parliament in May 1996, enshrining a series of institutions to place checks on political and administrative authority within a constitutional democracy.[303] De Klerk opposed the implementation of this constitution, and that month he and the National Party withdrew from the coalition government in protest, claiming that the ANC were not treating them as equals.[304] The ANC took over the cabinet positions formerly held by the Nationals, with Mbeki becoming sole Deputy President.[305] Inkatha remained part of the coalition,[306] and when both Mandela and Mbeki were out of the country in September 1998, Buthelezi was appointed "Acting President", marking an improvement in his relationship with Mandela.[307] Although Mandela had often governed decisively in his first two years as president,[308] he had subsequently increasingly delegated duties to Mbeki, retaining only a close personal supervision of intelligence and security measures.[309] During a 1997 visit to London, he said that "the ruler of South Africa, the de facto ruler, is Thabo Mbeki" and that he was "shifting everything to him".[308]

Mandela stepped down as ANC President at the party's December 1997 conference. He hoped that Ramaphosa would succeed him, believing Mbeki to be too inflexible and intolerant of criticism, but the ANC elected Mbeki regardless.[310] Mandela and the Executive supported Jacob Zuma, a Zulu who had been imprisoned on Robben Island, as Mbeki's replacement for Deputy President. Zuma's candidacy was challenged by Winnie, whose populist rhetoric had gained her a strong following within the party, although Zuma defeated her in a landslide victory vote at the election.[311]

Mandela's relationship with Machel had intensified; in February 1998, he publicly stated that he was "in love with a remarkable lady", and under pressure from Tutu, who urged him to set an example for young people, he organised a wedding for his 80th birthday, in July that year.[312] The following day, he held a grand party with many foreign dignitaries.[313] Although the 1996 constitution allowed the president to serve two consecutive five-year terms, Mandela had never planned to stand for a second term in office. He gave his farewell speech to Parliament on 29 March 1999 when it adjourned prior to the 1999 general elections, after which he retired.[314] Although opinion polls in South Africa showed wavering support for both the ANC and the government, Mandela himself remained highly popular, with 80% of South Africans polled in 1999 expressing satisfaction with his performance as president.[315]

Post-presidency and final years

Continued activism and philanthropy: 1999–2004

Retiring in June 1999, Mandela aimed to lead a quiet family life, divided between Johannesburg and Qunu. Although he set about authoring a sequel to his first autobiography, to be titled The Presidential Years, it remained unfinished and was only published posthumously in 2017.[316] Mandela found such seclusion difficult and reverted to a busy public life involving a daily programme of tasks, meetings with world leaders and celebrities, and—when in Johannesburg—working with the Nelson Mandela Foundation, founded in 1999 to focus on rural development, school construction, and combating HIV/AIDS.[317] Although he had been heavily criticised for failing to do enough to fight the HIV/AIDS pandemic during his presidency, he devoted much of his time to the issue following his retirement, describing it as "a war" that had killed more than "all previous wars"; affiliating himself with the Treatment Action Campaign, he urged Mbeki's government to ensure that HIV-positive South Africans had access to anti-retrovirals.[318] Meanwhile, Mandela was successfully treated for prostate cancer in July 2001.[319][320]

In 2002, Mandela inaugurated the Nelson Mandela Annual Lecture, and in 2003 the Mandela Rhodes Foundation was created at Rhodes House, University of Oxford, to provide postgraduate scholarships to African students. These projects were followed by the Nelson Mandela Centre of Memory and the 46664 campaign against HIV/AIDS.[321] He gave the closing address at the XIII International AIDS Conference in Durban in 2000,[322] and in 2004, spoke at the XV International AIDS Conference in Bangkok, Thailand, calling for greater measures to tackle tuberculosis as well as HIV/AIDS.[323] Mandela publicised AIDS as the cause of his son Makgatho's death in January 2005, to defy the stigma about discussing the disease.[324]

Publicly, Mandela became more vocal in criticising Western powers. He strongly opposed the 1999 NATO intervention in Kosovo and called it an attempt by the world's powerful nations to police the entire world.[325] In 2003, he spoke out against the plans for the United States to launch a war in Iraq, describing it as "a tragedy" and lambasting US president George W. Bush and British prime minister Tony Blair (whom he referred to as an "American foreign minister") for undermining the UN, saying, "All that (Mr. Bush) wants is Iraqi oil".[326] He attacked the United States more generally, asserting that "If there is a country that has committed unspeakable atrocities in the world, it is the United States of America", citing the atomic bombing of Japan; this attracted international controversy, although he later improved his relationship with Bush.[327][328] Retaining an interest in the Lockerbie suspect, he visited Megrahi in Barlinnie prison and spoke out against the conditions of his treatment, referring to them as "psychological persecution".[329]

"Retiring from retirement": 2004–2013