Manasija

Monastery church with main Despot's tower. | |

| Monastery information | |

|---|---|

| Full name | Манастир Манасија Manastir Manasija |

| Other names | Resava (Ресава) |

| Order | Serbian Orthodox |

| Established | 1406–1418 |

| Dedicated to | Holy Trinity |

| People | |

| Founder(s) | Stefan Lazarević |

| Site | |

| Location | Despotovac, Serbia |

| Visible remains | Stefan Lazarević Vuk Lazarević |

| Public access | Yes[1] |

| Type | Cultural Monument of Exceptional Importance |

| Designated | 5 March 1948 |

| Reference no. | SK 140[2] |

The Manasija Monastery (Serbian: Манастир Манасија, romanized: Manastir Manasija, pronounced [manǎsija]) also known as Resava (Ресава, pronounced [rɛ̌saʋa]), is a Serbian Orthodox monastery near Despotovac, Serbia founded by Despot Stefan Lazarević between 1406 and 1418.[3] The church is dedicated to the Holy Trinity. It is one of the most significant monuments of medieval Serbian culture and it belongs to the "Morava school".[3] The monastery is surrounded by massive walls and towers. Following its foundation, the monastery became the cultural centre of the Serbian Despotate.[4] Its School of Resava was well known for its manuscripts and translations throughout the 15th and 16th centuries.[5][6] Manasija complex was declared Monument of Culture of Exceptional Importance in 1979, and it is protected by Republic of Serbia, and the monastery entered the UNESCO Tentative List Process in 2010.[3]

Architecture and history

The founding charter of the monastery has not been preserved. The Manasija Monastery, also known as Resava, was built two kilometres northwest from the town of Despotovac, in the picturesque ravine.[7] Construction of the monumental mausoleum and the fortified town lasted about a decade. During this period, a church, large refectory, adjacent buildings, towers and walls, fortifications with protective walls and trenches were constructed.[8][9]

…across hills and fields and deserts he went looking for a place on which to build the desired family, the silent home. Having found the most suitable and the best site to build the home and having said a prayer, he approached the task and laid the foundations in the name of the Holy Trinity, universal Divinity…" (Constantine the Philosopher, 1433[9])

Monastery founder Despot Stefan Lazarević built Manasija to serve as his mausoleum.[9] The monumental and imposing Church of Manasija, together with the contemporary monuments (such as Ravanica, Ljubostinja, and Kalenić), bear witness to the last great artistic achievement of Morava's Serbia.[10]

The refectory was built parallel to the church,[9] and is one of the largest known structures in medieval Serbia, which was completely covered in frescoes. The monastery compound was encircled and protected by strong walls with eleven towers and trenches.

The monastery complex consists of:[11]

- The church to the Holy Trinity

- The refectory, placed to the south of the church

- The fortress with 11 towers, the largest of which is the keep, also known as the Despot's Tower (to the north of the church), with living quarters for the monks and other buildings

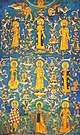

The Church of Manasija Monastery was consecrated on the Feast of Pentecost /Whitsun/ in 1418, after about 2,000 square metres of frescoes had been painted. Only a quarter of the paintings survived. History records that Despot Stefan invested great effort in finding the "most honoured and skillful workers, the most experienced icon painters".[citation needed]

During the five centuries of Ottoman presence, the monastery was abandoned and wrecked several times. The lead roof was removed from the church, and so for over a century the frescoes inside were subject to damage by rainfall.[12] As a result, about two-thirds of them were irremediably lost.[10] In the 18th century, the western part of the church - the narthex - was heavily damaged in an explosion and was later rebuilt.[13] The mosaic floor of that part of the church was partially preserved.[13]

Architecturally, the church belongs to the Morava school.[3] The ground plan is in the form of a floral inscribed cross, combined with a trefoil. The twelve-sided dome above the central space rests on four free-standing pillars.[14] At the eastern end, there are one large and two small apses, whereas two large choir conches flank the altar. Above the corners of the church, there are four small octagonal domes.[14] The narthex consists of nine bays. Above the central bay, there is yet another dome that rests on four pillars.[14] The church was built on ashlars and thin mortar beds. The facade decoration includes low pilasters, engaged colonettes on the conches and apses, as well as a frieze of small blind arcades on brackets running below the roof cornice.[14]

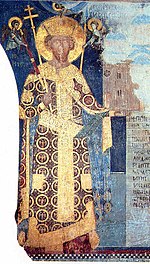

On the inside, the original floor has been preserved in the narthex, made of marble tiles in various colors. Despot Stefan is portrayed with the church model on the left-hand wall.[14] The lower register of the north choir depicts warrior-saints in armour with swords and lances, as an authentic representation of contemporaneous soldiers. The vault above the main door contains a picture of the Souls of the Righteous held by the Divine hand.[14] On the left and right, the prophets David and Solomon are portrayed respectively. There are also 24 portraits of the Old Testament prophets and patriarchs in the spacious dome. Two compositions cover the whole first and second registers in the altar: the first represents the Adoration of the Lamb, the other the Communion of Apostles.[14] The towers are mostly rectangular, save for two hexagonal ones and one square-shaped.

An archaeological team from the United Kingdom led by Marin Brmbolić,[15] located the remains of a person whom some claim to be Despot Stefan Lazarević in the southwestern part of the monastery floor. DNA comparison with the remains of his father, Knez Lazar, confirmed that the remains belong to two closely related individuals. However, there is no doubt that Stefan's brother Vuk was buried in Manasija and the remains could as well easily be his.[citation needed] The Serbian Orthodox Church has already officially proclaimed the remains in the Koporin Monastery, a smaller legacy of his, as those of Despot Stefan.[citation needed]

Burials

Gallery

- Mankind in God's hand. Fresco from the entrance in the west wall. Painted 1410-1418.

- Side view of monastery church

- Monastery fortifications.

- Manasija monastery overview

- Entrance is through west walls

- Tomb of despot Stefan Lazarević

See also

References

- ^ "Манастир Манасија". nasledje.gov.rs.

- ^ "Информациони систем непокретних културних добара".

- ^ a b c d Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Fortified Manasija Monastery". UNESCO World Heritage Centre.

- ^ Panić-Surep, Milorad (1965). Yugoslavia: Cultural Monuments of Serbia. Turistička štampa. p. 32.

- ^ Federici, F.; Tessicini, D., eds. (2014). Translators, Interpreters, and Cultural Negotiators: Mediating and Communicating Power from the Middle Ages to the Modern Era. Springer. p. 1964, 1971-1972. ISBN 9781137400048.

- ^ Matejic, Mateja; Milivojevic, Dragan Dennis (1978). An Anthology of Medieval Serbian Literature in English. Slavica Publishers. p. 24. ISBN 9780893570552.

- ^ Yugoslavia: Hotel and Tourist Directory. Privredni pregled. 1976. p. 189.

- ^ Andrejic, Ivan (5 July 2021). "Manasija Monastery – a jewel of medieval Serbian architecture". secretsedition.com.

- ^ a b c d "Manasija Monastery". artsandculture.google.com. Ministry of Culture of the Republic of Serbia.

- ^ a b Dunford, Martin; Holland, Jack, eds. (1990). "The Morava School Monasteries". The Real Guide: Yugoslavia. Prentice Hall. pp. 307–308. ISBN 9780137838387.

- ^ Ćurčić, Slobodan; Chatzētryphōnos, Euangelia, eds. (1997). Secular Medieval Architecture in the Balkans 1300-1500 and Its Preservation. Aimos, Society for the Study of the Medieval Architecture in the Balkans and its Preservation. p. 236. ISBN 9789608605916.

- ^ "Manasija Monastery - Winterfell in the heart of Serbia". castlesandfamilies.com.

- ^ a b "On the road with us to Manasija monastery and Resava cave". nisgazprom.rs. 20 November 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g Mileusnić, Slobodan (1998). Medieval monasteries of Serbia. Pravoslavna reč. pp. 120–125, 182. ISBN 9788676393701.

- ^ "Historical Abstracts: Modern history abstracts, 1775-1914. Part A". American Bibliographical Center, CLIO. July 11, 1991 – via Google Books.