Mamucium

| Mamucium | |

|---|---|

| |

| General information | |

| Architectural style | Roman fort |

| Location | Manchester, England |

| Coordinates | 53°28′33″N 2°15′03″W / 53.475962°N 2.250891°W |

| Completed | 79 |

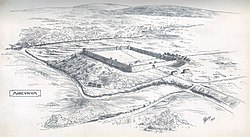

Mamucium, also known as Mancunium, is a former Roman fort in the Castlefield area of Manchester in North West England. The castrum, which was founded c. AD 79 within the Roman province of Roman Britain,[1] was garrisoned by a cohort of Roman auxiliaries near two major Roman roads running through the area. Several sizeable civilian settlements (or vicus) containing soldiers' families, merchants and industry developed outside the fort. The area is a protected Scheduled Ancient Monument.[2]

The ruins were left undisturbed until Manchester expanded rapidly during the Industrial Revolution in the late 18th century. Most of the fort was levelled to make way for new developments such as the construction of the Rochdale Canal and the Great Northern Railway. The site is now part of the Castlefield Urban Heritage Park that includes renovated warehouses. A section of the fort's wall along with its gatehouse, granaries, and other ancillary buildings from the vicus have been reconstructed and are open to the public.

Etymology

Mamucium is generally thought to represent a Latinisation of an original Brittonic name, either from mamm- ("breast", in reference to a "breast-like hill")[3][4] or from mamma ("mother", in reference to a local river goddess). Both meanings are preserved in modern Celtic languages, mam meaning "mother" in Welsh.[5][6] The neuter suffix -ium is used in Latin placenames, particularly those representing Common Brittonic -ion (a genitive suffix denoting "place or city of ~"). The Welsh name for Manchester is Manceinion. It appears that William Baxter invented this name in his ‘Glossarium Antiquitatum Britannicarum’ (1719) as a back-formation based on ‘Mancunium’. ‘Historia Brittonum’ (828-29) lists ‘Cair Maunguid’ (fort of the peat trees) and it has been suggested that this might be the authentic Welsh name for ‘Manchester’. In Modern Welsh, it would have been ‘*Caerfawnwydd’. It should be stressed that the ancient name is unknown. However, if one is correct to equate the 9th-century name with ‘Manchester’, the Proto-Celtic name would have been ‘*Māniwidion’. Roman authorities give both Mancunium and Mamucium, but it is not clear that either form is correct. Possibly neither is and they might be scribal errors for ‘*Maniuidium’.

Location

The Romans built the fort on a naturally defensible sandstone bluff that overlooked a nearby crossing over the River Medlock.[7] The area became an important junction for at least two major military roads through this part of the country. One highway ran east to west between the legionary fortresses of Deva Victrix (Chester) and Eboracum (York) the other ran north to Bremetennacum (Ribchester).[8] In addition, Mamucium may also have overlooked a lesser road running north west to Coccium (Wigan).[9] The fort was one of a chain of fortifications along the Eboracum to Deva Victrix road, with Castleshaw Roman fort lying 16 miles (26 km) to the east,[10] and Condate (Northwich) 18 miles (29 km) to the west. Stamps on tegulae indicate that Mamucium had administrative links not only with Castleshaw, but also with Ardotalia, the nearest fort (12 miles), Slack and Ebchester; all the forts probably got the tegulae from the same place in Grimescar Wood near Huddersfield.[11]

History

Prehistoric

There is no evidence that a prehistoric settlement occupied the site before the arrival of the Romans. However, Stone Age activity has been recorded in the area. Two Mesolithic flints and a flint flake as well as a Neolithic scraper have been discovered. A shard of late Bronze Age pottery has also been found in situ.[12] In 1772 during work to widen a canal a D-shaped gold bulla was dredged from the River Irwell; this item was subsequently lost but detailed drawings survive which show it to have been very similar to the late Bronze Age Shropshire bulla found in 2018.[13] Although the area was in the territory of the Celtic tribe Brigantes, it may have been under the control of the Setantii, a sub-tribe of the Brigantes, when the Romans took control from the ancient Britons.[14]

Roman

Construction of Mamucium started around AD 79[15] during the campaigns of General Julius Agricola against the Brigantes after a treaty failed.[16] Excavations show the fort had three main phases of construction: first AD 79, second around AD 160, and third in AD 200.

The first phase of the fort was built from turf and timber.[15] Mamucium's dimensions indicate it was to be garrisoned by a cohort, about 500 infantry. These troops were not Roman citizens but foreign auxiliaries who had joined the Roman army.[17] By the late 1st and early 2nd centuries, a civilian settlement (called a vicus) had grown up around the fort.[18] Around AD 90, the fort's ramparts were strengthened.[15] This might be because Mamucium and the Roman fort at Slack – which neighboured Castleshaw – superseded the fort at Castleshaw in the 120s.[19] Mamucium was demolished some time around AD 140.[15] Although the first vicus grew rapidly in the early 2nd century,[20] it was abandoned some time between 120 and 160 – broadly coinciding with the demolition of the fort – before it was re-inhabited when the fort was rebuilt.[21]

The second phase was built around the year 160. Although it was again of turf and timber construction, it was larger than the previous fort, measuring 2 hectares (4.9 acres) to accommodate extra granaries (horrea).[22] Around 200, the gatehouses of the fort were rebuilt in stone and the walls surrounding the fort were given a stone facing.[22] The concentration of furnaces in sheds in part of the vicus associated with the fort has been described as an "industrial estate",[23] which would have been the first in Manchester. Mamucium was included in the Antonine Itinerary, a 3rd-century register of roads throughout the Roman Empire.[24] This and inscriptions on and repairs to buildings indicate that Mamucium was still in use in the first half of the 3rd century.[25] The vicus may have been abandoned by the mid-3rd century; this is supported by the excavated remains of some buildings that were demolished and the materials robbed for use elsewhere.[21] Evidence from coins indicates that although the civilian settlement associated with the fort had declined by the mid-3rd century, a small garrison may have remained at Mamucium into the late 3rd century and early 4th century.[21]

A temple to Mithras is possibly associated with the civilian settlement[17] in modern Hulme.[26] An altar dedicated to Fortuna Conservatrix, "Fortune the Preserver", was found, probably dating to the early 3rd century.[17] In 2008 an altar dating from the late 1st century was discovered near the Roman settlement. It was dedicated to two minor Germanic gods and described as being in "fantastic" condition.[27] The County Archaeologist said

It's the first Roman stone inscription to be found in Manchester for 150 years and records only the second known Roman from Manchester ... The preservation of the stone is remarkable. On top of the stone is a shallow bowl which was used for offerings of wine or blood or perhaps to burn incense.

— Norman Redhead[28]

As well as Pagan worship, there is also evidence of early Christian worship. In the 1970s, a fragment of 2nd-century "word square" was discovered with an anagram of PATER NOSTER.[29] There has been discussion by academics whether the "word square", which is carved on a piece of amphora, is actually a Christian artefact, if so, it is one of the earliest examples of Christianity in Britain.[30]

Medieval

After the Roman withdrawal from Britain around 410, the area of Mamucium was used for agricultural purposes.[21] It has sometimes been identified with the Cair Maunguid[31] listed among the 28 cities of Britain by the History of the Britons traditionally attributed to Nennius.[32][33]

16th–18th centuries

After lying derelict for centuries, the ruins were commented on by antiquarians John Leland in the 16th century, William Camden in the late 16th and early 17th centuries, and William Stukeley[9] and the Manchester historian John Whitaker in the 18th century. In the early 18th century, John Horsley said:

It [i.e., the fort] is about a quarter of a mile out of the town, being south or south-west from it. The station now goes by the name of Giant's Castle or Tarquin's Castle,[35] and the field in which it stands is called Castle Field ... the ramparts are still very conspicuous.

— John Horsley, Britannia Romana[34]

Whitaker described what remained of the fort in 1773:

The eastern side, like the Western, is hundred and forty [yards] in length, and for eighty yards from the northern termination, the nearly perpendicular rampart carries a crest of more than two [yards] in height. It is then lowered to form the great entrance, the Porta Pretoria of the camp: the earth there running in a ridge, and mounting up to the top of the bank, about ten in breadth. Then, rising gradually as the wall falls away, it carries a height of more than three for as many as the south-eastern angle. And the whole of this wall, bears a broken line of thorns above, shews the mortar peeping here and there under the coat of turf, and near the south-eastern corner has a large buttress of earth continued several yards along it. The southern side, like the Northern, is hundred and seventy five [yards] in length; and the rampart sinking immediately from its elevation at the eastern end, successively declines, till, about fifty yards off, it is reduced to the inconsiderable height of less than one [yard]. And about seventeen yards further, there appears to have been a second gateway, the ground rising up to the crest of the bank of a four or five at the point ...

On the south side was particularly requisite ... in order to afford a passage to the river; but about fifty three yards beyond the gates, the ground betwixt both falling away briskly to the west, the rampart, which continues in a right line along the ridge, necessarily rises till it has a sharp slope of twenty yards in length at the southwestern angle. And all this side of the wall, which was from the beginning probably not much higher than it is at present, as it was sufficiently secured by the river and its banks, before it appears crested at first with a hedge of thorns, a young oak rising from the ridge and rearing its head considerably over the rest, and runs afterwards in a smooth line near the level for several yards with the ground about it, and just perceptible to the eye, in a rounded eminence of turf

As to the south-western point of the camp, the ground slopes away on the west towards the south, as well as on the south towards the West. On the third side still runs from it nearly as at first, having an even crest about seven feet in height, an even slope of turf for its whole extent, and the wall in all its original condition below. About a hundred yards beyond the angle was the Porta Decumana of the station, the ground visibly rising up the ascent of the bank in a large shelve of gravel, and running in a slight but perceivable ridge from it. And beyond a level of forty five yards, that still stretches on for the whole length of the side, it was bounded by the western boundary of the British city, the sharp slope of fifty to the morass below it. On the northern and remaining side are several chasms in the original course of the ramparts. And in one of them about a hundred and seventy five yards from its commencement, was another gateway, opening into the station directly from the road to Ribchester. The rest of the wall still rises above five and four feet in height, planted all the way with thorns above, and exhibiting a curious view of the rampart below. Various parts of it have been fleeced of their facing a turf and stone, and now show the inner structure of the whole, presenting to the eye the undressed stone of the quarry, the angular pieces of rock, and the round boulders of the river, all bedded in the mortar, and compacted into one. And the white and brown patches of mortar and stone on a general view of the wall stands strikingly contrasted with the green turf that entirely conceals the level line, and with the green moss that half reveals the projecting points of the rampart. The great foss of the British city, the Romans preserved along their northern side for more than thirty yards along the eastern end of it, and for the whole beyond the Western. And as the present appearances of the ground intimate, they closed the eastern point of it with a high bank, which was raised upon one part of the ditch and sloped away into the other.

— John Whitaker, History of Manchester vol I (1773 edition)[36]

Industrial Revolution

Mamucium was levelled as Manchester expanded in the Industrial Revolution. The construction of the Rochdale Canal through the south western corner of the fort in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, and the building of viaducts for the Great Northern Railway over the site in the late 19th century, damaged the remains and even destroyed some of the southern half of the fort.[9] When the railway viaducts were built, Charles Roeder documented the remains that were uncovered in the process, including parts of the vicus.[9] Mills were all around the site. Castlefield became the south west corner of Manchester city centre.[9] Deansgate, which developed into the main thoroughfare, follows the general line of Roman road to Ribchester.[9]

20th century

The first archaeological investigation of Mamucium was in 1906. Francis Bruton, who would later work on the Roman fort at Castleshaw, excavated the fort's western defences.[15] A series of small-scale excavations were undertaken intermittently between 1912 and 1967, generally exploring the northern defences of the fort.[15][37] In the mid-20th century, historian A. J. P. Taylor called the surviving stretch of Roman wall "the least interesting Roman remains in Britain".[38] The first excavation of the vicus was carried out in the 1970s under Professor Barri Jones.[15] In 1982 the fort, along with the rest of the Castlefield area, became the United Kingdom's first Urban Heritage Park,[39][40] and partial reconstructions of the forts walls, including the ramparts and gateways, were opened in 1984.[17] In 2001–05 the University of Manchester Archaeological Unit carried out excavations in the vicus to further investigate the site before the area underwent any more regeneration or reconstruction.[7] The archaeological investigation of Mamucium Roman fort and its associated civilian settlement has, so far, provided approximately 10,000 artefacts.[12]

Layout

The fort measured 160 metres (175 yd) by 130 metres (140 yd) and was surrounded by a double ditch and wooden rampart. Around AD 200 the wooden rampart was replaced by stone ramparts,[41] measuring between 2.1 metres (7 ft) and 2.7 metres (9 ft) thick.[26] The vicus associated with Mamucium surrounded the site on the west, north, and east sides, with the majority lying to the north. The vicus covered about 26 hectares (64 acres) and the fort about 2 hectares (4.9 acres).[9] Buildings within the vicus would have generally been one storey, timber framed, and of wattle and daub construction.[41] There may have been a cemetery to the south east of the fort.[26]

Templeborough Roman Fort in Yorkshire was rebuilt in stone in the 2nd century and covered an area of 2.2 hectares (5.5 acres),[42] similar to Mamucium which covered 2.0 hectares (4.9 acres).

See also

References

- ^ Rivet, A L F; Smith, Colin (1979). The Place-Names of Roman Britain. London: B T Batsford.

- ^ Historic England. "Mamucium (76731)". Research records (formerly PastScape). Retrieved 29 December 2007.

- ^ Mills, A.D. (2003). A Dictionary of British Place-Names. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-852758-6.

- ^ Hylton (2003), p. 6.

- ^ The Antiquaries Journal (ISSN 0003-5815) 2004, vol. 84, pp. 353–357

- ^ Mills, A.D. (2003). A Dictionary of British Place-Names. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-852758-6. Retrieved 7 November 2013.

- ^ a b Gregory (2007), p. 1.

- ^ Gregory (2007), pp. 1–2.

- ^ a b c d e f g Gregory (2007), p. 2.

- ^ Walker (1999), p. 15.

- ^ Walker (1999), p. 78.

- ^ a b Gregory (2007), p. 181.

- ^ Current Archaeology, March 11, 2019:https://archaeology.co.uk/articles/features/the-shropshire-bulla-bronze-age-beauty-and-a-mystery-from-manchester.htm

- ^ Kidd (1996), p. 12.

- ^ a b c d e f g Gregory (2007), p. 3.

- ^ Mason (2001), pp. 41–42.

- ^ a b c d Norman Redhead (20 April 2008). "A guide to Mamucium". BBC. Retrieved on 20 July 2008.

- ^ Gregory (2007), pp. 22, 156.

- ^ Nevell and Redhead (2005), p. 59.

- ^ Gregory (2007), p. 183.

- ^ a b c d Gregory (2007), p. 190.

- ^ a b Philpott (2006), p. 66.

- ^ Shotter (2004), p. 117.

- ^ Shotter (2004), p. 40.

- ^ Shotter (2004), p. 153.

- ^ a b c Hylton (2003), p. 4.

- ^ David Ottewell (10 April 2008). "Roman soldier's gift found". Manchester Evening News. Retrieved on 20 July 2008.

- ^ "Offering up the past". BBC. 10 April 2008. Retrieved on 20 July 2008.

- ^ AE 1979, 00387 Shotter (2004), p. 129.

- ^ Shotter (2004), pp. 129–130.

- ^ Nennius (attrib.). Theodor Mommsen (ed.). Historia Brittonum, VI. Composed after AD 830. (in Latin) Hosted at Latin Wikisource.

- ^ Ford, David Nash. "The 28 Cities of Britain Archived 15 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine" at Britannia. 2000.

- ^ Newman, John Henry & al. Lives of the English Saints: St. German, Bishop of Auxerre, Ch. X: "Britain in 429, A. D.", p. 92. Archived 21 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine James Toovey (London), 1844.

- ^ a b Hylton (2003), p. 3.

- ^ The name "Tarquin's Castle" refers to the legend that the fort had been occupied by a giant named Tarquin.[34]

- ^ Fishwick, Henry (1968) [1894]. "IV Roman remains". A History of Lancashire. County History Reprints. Wakefield, Yorkshire: S.R. Publishers Ltd. p. 22.

- ^ "Mamucium investigation history". Pastscape.org.uk. Retrieved on 18 July 2008.

- ^ Nevell (2008), p. 19.

- ^ Woodside et al. (2004), p. 286.

- ^ Manchester City Council. "Manchester firsts". Government of the United Kingdom. Retrieved 15 July 2008.

- ^ a b Hylton (2003), p. 2.

- ^ Historic England. "Templeborough Roman Fort (316617)". Research records (formerly PastScape). Retrieved 20 June 2015.

Bibliography

- Gregory, Richard, ed. (2007). Roman Manchester: The University of Manchester's Excavations within the Vicus 2001–5. Oxford: Oxbow Books. ISBN 978-1-84217-271-1.

- Hylton, Stuart (2003). A History of Manchester. Chichester: Phillimore and co. Ltd. ISBN 1-86077-240-4.

- Kidd, Alan (1996) [1993]. Manchester. Keele: Keele University Press. ISBN 1-85331-182-0.

- Mason, David J.P. (2001). Roman Chester: City of the Eagles. Stroud: Tempus Publishing Ltd. ISBN 0-7524-1922-6.

- Nevell, Mike (2008). Manchester: The Hidden History. The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-4704-9.

- Nevell, Mike; Redhead, Norman, eds. (2005). Mellor: Living on the Edge. A Regional Study of an Iron Age and Romano-British Upland Settlement. University of Manchester Archaeological Unit, Greater Manchester Archaeological Unit, and the Mellor Archaeological Trust. ISBN 0-9527813-6-0.

- Philpott, Robert A. (2006). "The Romano-British Period Resource Assessment". Archaeology North West. 8: 59–90. ISSN 0962-4201.

- Roeder, Charles (1900). .

- Shotter, David (2004) [1993]. Romans and Britons in North-West England. Lancaster: Centre for North-West Regional Studies. ISBN 1-86220-152-8.

- Walker, John, ed. (1989). Castleshaw: The Archaeology of a Roman Fortlet. Greater Manchester Archaeological Unit. ISBN 0-946126-08-9.

- Woodside, Arch; et al. (2004). Consumer Psychology of Tourism, Hospitality, and Leisure. CABI Publishing. ISBN 0-85199-535-7.