Hungarian State Railways

| MÁV-VOLÁN-csoport | |

| |

MÁV-START Stadler FLIRT trains waiting at Gödöllő | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Headquarters | |

| Key people | Zsolt Hegyi CEO |

| Locale | Hungary |

| Dates of operation | 1869– |

| Predecessor | Hungarian Royal State Railways |

| Technical | |

| Track gauge | 1,435 mm (4 ft 8+1⁄2 in) |

| Length | 7,606 km (4,730 mi) |

| Other | |

| Website | www |

Hungarian State Railways (Hungarian: Magyar Államvasutak, pronounced [ˈmɒɟɒr ˈaːlːɒɱvɒʃutɒk], formally MÁV Magyar Államvasutak Zártkörűen Működő Részvénytársaság (MÁV Zrt.). The full official name of the company is MÁV-VOLÁN-csoport (lit. '"MÁV-VOLÁN Group"') now commonly known as MÁV) is the Hungarian national railway company and the MÁV Zrt. is the railway infrastructure manager, with subsidiaries "MÁV-START Zrt." (passenger services), and "Utasellátó" (onboard catering, Utasellátó is an independent directorate of MÁV-START Zrt.).[1]

The head office is in Budapest.[2]

History

1846–1918

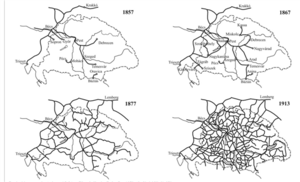

Construction of Hungary's first railway line began in the second half of 1844. The first steam locomotive railway line was opened on 15 July 1846 between Pest and Vác. This date is regarded as the birth date of the Hungarian railways. The Romantic poet Sándor Petőfi rode on the first train and wrote a poem predicting that rails would connect Hungary like blood vessels in the human body.

After the failed revolution, the existing lines were nationalized by the Austrian State and new lines were built. As a result of the Austro-Sardinian War in the late 1850s, all these lines were sold to Austrian private companies. During this time the company of Ábrahám Ganz invented a method of "crust-casting" to produce cheap yet sturdy iron railway wheels, which greatly contributed to railway development in Central Europe.

Following the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867 that created the Dual Monarchy of Austria-Hungary, transport issues became the responsibility of the Hungarian Government, which also inherited the duty to support local railway companies. This came at a considerable cost: in 1874 8% of the annual budget went to railway company subsidies. This led the Hungarian Parliament to consider founding a State Railway. The goal was to take over and operate the Hungarian main lines. The branch lines were constructed by private companies. When the law in 1884 provided a simplified way to create railway companies many small branch line companies were founded. These, however, usually only constructed the lines, then made a contract with MÁV to operate them. Thus they also owned no locomotives or other rolling stock. MÁV made a contract only if the line, its equipment and buildings were constructed to MÁV standards. This helped to build standard station buildings, sheds, and accessories, all to the MÁV rules.

Because of relatively high prices the traffic density was considerably lower in Hungary than in other countries. To change this the Interior Minister, Gábor Baross, introduced the zone tariff system in 1889. This system resulted in lower prices for passenger trips and goods transport but it induced a rapid increase in both and so higher overall profits. In 1891 the Hungarian lines of the StEG were bought by the Hungarian State directly from the French owners and became MÁV lines.

In 1890 most large private railway companies were nationalized as a consequence of their poor management, except the strong Austrian-owned Kaschau-Oderberg Railway (KsOd) and the Austrian-Hungarian Southern Railway (SB/DV). They also joined the zone tariff system, and remained successful until the end of World War I when Austria-Hungary collapsed.

By 1910 MÁV had become one of the largest European railway companies, in terms of both its network and its finances. Its profitability, however, always lagged most Western European companies, be they publicly or privately owned. The Hungarian railway infrastructure was largely completed in these years, with a topology centred on Budapest that still remains.

By 1910, the total length of the rail networks of the Hungarian Kingdom reached 22,869 kilometres (14,210 miles), the Hungarian network linked more than 1,490 settlements. Nearly half (52%) of the Austro-Hungarian Empire's railways were built in Hungary, thus the railroad density there became higher than that of Cisleithania. This has ranked Hungarian railways the 6th most dense in the world (ahead of countries as Germany or France).[3]

In 1911 a new locomotive numbering system was introduced which was used until the beginning of the 21st century and is still in use for motive power purchased before then. The notation specifies the number of driven axles and the maximum axle load of the locomotive.

Hungarian locomotive factories

Despite the Hungarian factories were independent companies, the largest suppliers of MÁV were the MÁVAG company in Budapest (steam engines and wagons) and the Ganz company in Budapest (steam engines, wagons, the production of electric locomotives and electric trams started from 1894).[4] and the RÁBA Company in Győr.

- The first steam railcar built by Ganz and de Dion-Bouton

- The four-cylinder 2,950 hp (2,200 kW) MÁV Class 601 was the strongest steam locomotive of pre WW1 Europe.[5][6][7]

- Ganz AC electric locomotive prototype (1901 Valtellina, Italy)

- Electric locomotive RA 361 (later FS Class E.360) by Ganz for the Valtellina line, 1904

- MÁV armoured train during the WW I

- The world's first locomotive with a phase converter was Kandó's V50 locomotive (only for demonstration and testing purposes)

The Ganz Works identified the significance of induction motors and synchronous motors commissioned Kálmán Kandó (1869–1931) to develop it. In 1894, Kálmán Kandó developed high-voltage three-phase AC motors and generators for electric locomotives. The first-ever electric rail vehicle manufactured by Ganz Works was a 6 HP pit locomotive with direct current traction system. The first Ganz made asynchronous rail vehicles (altogether 2 pieces) were supplied in 1898 to Évian-les-Bains (Switzerland), with a 37-horsepower (28 kW), asynchronous-traction system. The Ganz Works won the tender of electrification of railway of Valtellina Railways in Italy in 1897. Italian railways were the first in the world to introduce electric traction for the entire length of a main line, rather than just a short stretch. The 106-kilometre (66 mi) Valtellina line was opened on 4 September 1902, designed by Kandó and a team from the Ganz works.[8] The electrical system was three-phase at 3 kV 15 Hz. The voltage was significantly higher than used earlier, and it required new designs for electric motors and switching devices.[9][10] In 1918,[11] Kandó invented and developed the rotary phase converter, enabling electric locomotives to use three-phase motors whilst supplied via a single overhead wire, carrying the simple industrial frequency (50 Hz) single phase AC of the high voltage national networks.[12]

1918–1939

At the end of World War I, after the peace treaty of Trianon that reduced Hungarian territory by 72%, the Hungarian railway network was cut from around 22,000 to 8,141 km (13,670 to 5,059 mi) (the 7,784 km or 4,837 mi long MÁV-owned network decreased to 2,822 km or 1,754 mi). The number of freight cars was 102,000 at the end of World War I, but after 1921 only 27,000 remained in Hungary, of which 13,000 were in working order. The total number of locomotives was 4,982 in 1919, but after the peace treaty, only 1,666 remained in Hungary. As many existing railway lines crossed Hungary's new borders, most of these branch lines were abandoned. On the main lines, new border stations had to be constructed with customs facilities and locomotive service.

Between the world wars, development focused on existing multiple-track lines and adding a second track to most main lines. An electrification process started, based on Kálmán Kandó's patent on a single-phase 16 kV 50 Hz AC traction and his newly designed MÁV Class V40 locomotive, which used a rotary phase converter unit to transform the catenary high voltage current into multiphase current with regulated low voltage that fed the single multi-phase AC induction traction motor. Most main lines' cargo and passenger trains were hauled by the MÁV Class 424 steam locomotive, which became the MÁV's workhorse in the late steam era. From 1928 onwards 4- and 6-wheeled gasoline (and later diesel) railcars were purchased (Class BCmot) and by 1935 57% of branch lines were served by railcars. The rest of MÁV's passenger network remained steam based with slow pre-war locomotives and 3rd class "wooden bench" carriages (called fapados in Hungarian, a name nowadays applied to low cost airlines).

In the early 1930s, almost all Hungarian branch line operators went bankrupt because of the Great Depression. DSA, the Hungarian successor to the former Austrian-Hungarian Southern Railway, went into receivership. MÁV took over DSA's branch lines and all property in 1932 and continued to operate them. MÁV thus became the only major railway operator in Hungary, the impact of the few other independent railway companies (GySEV, AEGV) being negligible.

1939–1950

Between 1938 and 1941 Hungary received temporary territorial gains from Czechoslovakia, Romania and Yugoslavia. The main goal of the MÁV was to reintegrate the newly returned rail network (that was originally built by MÁV, but several border crossings were dismantled). The biggest construction of the time was the Déda-Szeretfalva railway, because the new border in Transylvania after the Second Vienna Award cut the rail network into two parts with no connection, while Romania closed all newly created rail border crossings not allowing Hungarian domestic traffic through on the original main route. Despite all efforts, after losing the war, Hungary lost all newly gained territories.

During late World War II, MÁV was used to deport Jews in Hungary to Nazi concentration camps.[13] The Hungarian railway system subsequently suffered tremendous destruction. More than half the main lines and a quarter of the branch lines were inoperable. 85% of all bridges were destroyed, 28% of all buildings were ruined and another 32% of them inoperable. The rolling stock was either destroyed or distributed to many other European countries. Only 213 locomotives, 120 railcars (there was no fuel in the last days of the war to move them away), 150 passenger cars and 1,900 freight cars were in working order. These were prized and signed as "trophies" by the Soviet Red Army.

After World War II the track, buildings and service equipment were repaired with tremendous efforts in relatively short time. By 1948 most of the railway system was operable, some larger bridges needing more time to be rebuilt. The first electrified section was already in use by October 1945. The Red Army sold back the confiscated rolling stock and locomotives were returned from Austria and Germany. To accelerate reconstruction MÁV purchased 510 USATC S160 Class locomotives which became MÁV Class 411.

1950–2000

In the 1950s, an accelerated industrialization was ordered by the Hungarian Socialist Workers' Party and the railway was considered a backbone of these efforts. Overloaded trains were hauled by badly maintained locomotives on poor quality tracks. Unrealistic Five Year Plans were specified; not fulfilling them was considered sabotage. After accidents, railway workers were given show trials and sometimes even sentenced to death.

All the time the production of steam locomotives continued, but at first in small numbers, as the Hungarian industry was fully booked producing Soviet war reparations. This included steam locomotives to Soviet designs, passenger and freight cars, and many other goods. The development of diesel locomotives started. The successor of the Kandó V40 locomotives, the Class V55 proved to be a failure and MÁV decided to purchase no more phase converter engines.

During the 1956 Hungarian Revolution the railways were not seriously damaged. After the suppressed Revolution the system of Five-Year Plans was reintroduced but with lower targets. In 1958 steam locomotive manufacturing stopped in Hungary. 600 HP diesel-electric locomotives (Class M44) and 450 HP diesel hydraulic switchers (Class M31) were manufactured.

By 1964, the German-designed, domestically-built MÁV Class V43 four-axle 25 kV AC 50 Hz electric locomotive entered service and eventually some 450 of this reliable engine became the workhorse of MÁV traction in passenger as well as freight service. Heavy diesel engines arrived from the USSR (M62) and Sweden/United States (M61). Track maintenance, however, always remained poor, preventing the rolling stock from using the system to its fullest.

To this day 120 km/h (75 mph) (particularly 160 km/h (100 mph)) remains the top speed for trains in Hungary, though EU funds have become available to upgrade the network, especially tracks of the Trans-European Transport Networks. (Since Hungary lies in Central Europe, many important railway lines go through the country.) During the 1990s the state-owned MÁV gradually abandoned its most rural routes, but large scale passenger service cuts were blocked by political pressure. Still, the quality of general passenger service deteriorated considerably since Hungary converted to capitalism, as MÁV became focused on the more profitable cargo business. Relatively few people have access to the higher-quality "Intercity" express trains because of the unbalanced topography of the Hungarian railway network. Further expansion is also hampered by the shortage of high-quality passenger carriages.

2000–2010

As the post-2000 Hungarian political establishment became very much focused on the perceived "autobahn-gap" compared to better-routed Slovakia and especially Croatia and decided to upgrade the highway system, there was no significant domestic funding for developing the Hungarian Railway especially for the small regional lines. Recent developments include the purchase of twelve Siemens Desiro diesel railbuses for commuter routes and the order for Swiss Stadler Flirts, a type of very advanced electric self-propelled train for medium range shuttle paths, which is mired in a selection scandal against Bombardier's more established, but conservatively engineered Talent trains.

The GySEV Győr–Sopron–Ebenfurti Vasút Rt. line (connecting two Hungarian and one Austrian city) is managed jointly by the two states.

In 2006 the government was elected for promises, among those are making the lines between cities double-tracked, electrified, and validated for 160 km/h (by this transferring highway-cargo of companies to more environment-friendly, faster and greater capacity transportation). This was supposed to be done by first building the new track then building the remaining one in the place of the original one. The only possible way to finance the project was with the help of EU funds. EU supervision revised the plans and the projected cost but this delayed starting. During construction, the actual billings were also checked. Because of the delay and the lengthy construction works, most of the lines are still not opened in the planned state. The building works are largely forgotten by public consciousness because of the following:

On 7 December 2006, as part of a broader economic restriction package, the Hungarian government announced its intention to stop operation on 14 regional lines with a total length of 474 km (295 mi). The government, referring to an obligation under the constitution, ensured access to public transit in all settlements by installing bus routes and buses from Volánbusz Mass-Transit Company. This in cases when single railway stations served multiple villages, meant bus stations were established in the centers or ends of each settlement. This and increasing frequency theoretically can be done while eliminating the high fuel (diesel or electricity) consumption of the trains and their maintenance cost.

The first plans of János Kóka, Minister of the Economy and Transport, were more radical, abandoning 26 lines (or 12% of the entire network), but they were met with strong opposition from the local municipalities, parliamentary opposition parties and civic organizations. The main opposition party claimed that these measures were directed against more rural areas, especially small villages. The issue was heavily politicized. People considered the buses less safe or fast, especially in winter. Since the government wanted to avoid costly environmental protection and recultivation regulations, the railway lines will not be formally ceased, with the tracks removed, just the service suspended indefinitely. However, because of widespread scrap metal theft in Hungary, this effectively means the tracks are written off.

On 4 March 2007 service was suspended on 14 lines: Pápa–Környe, Pápa–Csorna, Zalabér–Zalaszentgrót, Lepsény–Hajmáskér, Sellye–Villány, Diósjenő–Romhány, Kisterenye–Kál–Kápolna, Mezőcsát–Nyékládháza, Kazincbarcika–Rudabánya, Nyíradony–Nagykálló, Békés–Murony, Kunszentmiklós–Dunapataj, Fülöpszállás–Kecskemét and Kiskőrös–Kalocsa. Many of these have since been reopened by the new government.

On 20 April 2007, the Index news web portal published material from internal MÁV studies, which indicated the new company leadership and the government intend to close all small regional railway lines after 2008, to eliminate sources of reincurring unfinanced expenses at MÁV (the to-be-closed lines' expenses are ten times as large as their incomes). This would leave only the international railway lines and large rural-to-town routes running.

However, in 2010, when Fidesz returned to power, the new government announced that they would undo a plethora of transportation decisions made by the socialists. Ten rural railway lines, previously closed with the reason of low revenues, were reopened with much fanfare. The government states both bus and railway system have to be developed, and most settlements shouldn't be limited to have only one type of station.

2010s

In the 2010s Hungary received large EU funds to modernize its rail network. These reconstruction works were concentrated on main corridor lines and suburban lines of Budapest, where most sections got complete overhauls. The branch lines were left in poor condition and still operate with old diesel railcars, speeds rarely exceed 60 km/h not receiving any funds for modernization. This caused the passenger numbers to stagnate, although the newly modernized suburban lines gained new passengers, the rural network was falling into a downward spiral.

In February 2013, for the first time in its history, the railway started to train women drivers. The Times quoted a spokesman as saying that since there are no steam trains, there is no need for heavy lifting.[14][15]

Currently, the premium IC+ coaches run on Intercity services to Szeged, to Lake Balaton and on the Circular Intercity service on the Budapest–Szolnok–Debrecen–Nyíregyháza–Miskolc–Budapest route, which includes all major cities in Eastern Hungary. 35 coaches are to be built in total. [16]

Railway stations

MÁV currently operates over 600 stations and 700 railway stops. Many of the railway's major, central stations (and also numerous major stations within the Austro-Hungarian Empire now located outside Hungary) were designed by Ferenc Pfaff and opened in the late 1880s and 1890s.

Budapest

- Déli Railway Station (South)

- Keleti Railway Station (East, Central)

- Nyugati Railway Station (West)

- Kelenföld Railway Station

- Kőbánya-Kispest Railway Station

- Ferihegy station

- Ferencváros Railway Station

- Kőbánya alsó station

- Kőbánya felső Railway Station

- Pestszentlőrinc station

- Szemeretelep station

- Újpalota station

- Zugló station

Miskolc

Pécs

- Pécs Railway Station

- Pécs-Külváros Railway Station

- Pécsbánya-Rendező Railway Station

Debrecen

- Debrecen Railway Station (Nagyállomás)

- Debrecen-Csapókert station

- Debrecen-Kondoros station

- Debrecen-Szabadságtelep station

- Tócóvölgy Railway Station

Szeged

- Szeged Railway Station

- Szeged-Rókus Railway Station

Győr

- Győr Railway Station

- Győr-Gyárváros station

- Győrszabadhely Railway Station

- Győrszentiván Railway Station

Nyíregyháza

- Nyíregyháza Railway Station

- Nyíregyháza külső Railway Station

As the only railway station on the first ever Hungarian railway line to remain in its original form, Vác station is essentially the oldest station building in Hungary (renovated in 2013).

Statistics

- Railway lines total: 7,606 km (4,726 mi)

- Standard gauge: 7,394 km (4,594 mi)

- Broad gauge: 36 km (22 mi) of 1,520 mm (4 ft 11+27⁄32 in)

- Narrow gauge: 176 km (109 mi)

Note: The standard and broad gauge railways are operated by the State Railways and also the following narrow gauge railways: Nyíregyháza–Balsai Tisza part/Dombrád; Balatonfenyves–Somogyszentpál; Kecskemét–Kiskunmajsa/Kiskőrös and the Children's Railway in Budapest. All the other narrow gauge railways are run by State Forest companies or local non-profit organisations. See also Narrow gauge railways in Hungary.

See also

- Rail transport in Hungary

- Transport in Hungary

- List of railway lines in Hungary

- Imperial Royal Austrian State Railways

- BHÉV

- List of Hungarian locomotives

References

- ^ "Viharos vasúteladások (Hungarian)". 7 August 2007.

- ^ "Contact Archived 23 September 2014 at the Wayback Machine." Hungarian State Railways. Retrieved on 23 April 2014. "H-1087 Budapest, Könyves Kálmán krt. 54-60."

- ^ Iván T. Berend (2003). History Derailed: Central and Eastern Europe in the Long Nineteenth Century (in Hungarian). University of California Press. p. 152. ISBN 9780520232990.

- ^ "Hipo Hipo – Kálmán Kandó(1869–1931)". Sztnh.gov.hu. 29 January 2004. Archived from the original on 14 May 2013. Retrieved 25 March 2013.

- ^ "VINCZE TAMÁS nyugalmazott MÁV igazgató : 100 éves a MÁV 601 sor. mozdonya" (PDF). Vasutgepeszet.hu. Retrieved 23 January 2018.

- ^ (Béla Czére, Ákos Vaszkó): Nagyvasúti Vontatójármüvek Magyarországon, Közlekedési Můzeum, Közlekedési Dokumentációs Vállalat, Budapest, 1985, ISBN 9635521618

- ^ Wolfgang Lübsen: Die Orientbahn und ihre Lokomotiven. in: Lok-Magazin 57, December 1972, pp. 448–452

- ^ Michael C. Duffy (2003). Electric Railways 1880–1990. IET. p. 137. ISBN 978-0-85296-805-5.

- ^ "Kalman Kando". Omikk.bme.hu. Retrieved 26 October 2011.

- ^ "Kalman Kando". Profiles.incredible-people.com. Archived from the original on 12 July 2012. Retrieved 5 December 2009.

- ^ Michael C. Duffy (2003). Electric Railways 1880–1990. IET. p. 137. ISBN 978-0-85296-805-5.

- ^ Hungarian Patent Office. "Kálmán Kandó (1869–1931)". www.mszh.hu. Archived from the original on 8 October 2010. Retrieved 10 August 2008.

- ^ Bravin, Jess (3 February 2021). "Supreme Court Denies Holocaust Victims' Property Claims Against Nazi Germany, Hungary". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 22 September 2024.

- ^ Először ülhet nő mozdonyra

- ^ "Hungary starts training women to be engine drivers". Budapest Business Journal (AFP). 5 February 2013.

- ^ "Már mindegyik kör-IC járatban utazhatunk az IC+ prémium fülkéjében". MÁV-csoport (in Hungarian). 30 December 2021. Retrieved 1 September 2023.

External links

- Official site of MÁV

- Official site of MÁV-Start (passenger trains operator)

- Rail Cargo Hungary (ex-MÁV, Rail Cargo Austria Group)

- Railway map - with junctions and track types

- Railway map - with all stations, Hungarian-German description

- Photographs of railway stations

- Railways and Tourism, Public Transport in Hungary

- Railway photos arranged on a map at benbe.hu

- Budapest public transport map

![The four-cylinder 2,950 hp (2,200 kW) MÁV Class 601 was the strongest steam locomotive of pre WW1 Europe.[5][6][7]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/5c/M%C3%A1v_Class_601_1914.jpg/150px-M%C3%A1v_Class_601_1914.jpg)