Layla and Majnun (Nizami Ganjavi poem)

|

| Part of a series on |

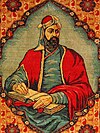

| Nizami Ganjavi |

|---|

| The Khamsa or Panj Ganj |

| Related topics |

| Monuments |

|

Nizami Mausoleum • Nizami Museum of Azerbaijani Literature • Nizami Gəncəvi (Baku Metro) • in Ganja • in Baku • in Beijing • in Chișinău • in Rome • in Saint Petersburg • in Tashkent |

"Layla and Majnun" (Persian لیلی و مجنون) is the third poem of the classic of Nizami Ganjavi (1141–1209, Ganja).[1][2] This poem is included in "Khamsa" and was written in 1188 in Persian. It is based on the story of the ancient Arabic legend "Layla and Majnun" about the unhappy love[3] of the young man Qays, nicknamed "Majnun" ("The Madman"), towards beautiful Layla. The poem is dedicated to Shirvanshah Ahsitan I, and was written on his order.[4] There are 4600 stanzas in the poem. This poem is considered as the first literary processing of the legend.[5]

Summary of the poem

The poet Qays[1] fell in love with his cousin Layla, but Layla had to marry another man: Qays went insane and retired to the desert, where he composed poems dedicated to the beloved Layla.[6] The couple united only after death. Nizami slightly modified the plot: Qays goes crazy with love, which leads Layla's parents to reject him. Layla, being forced to marry, dies due to her love for Qays, and is buried in a wedding dress. Upon learning of Layla's death, Majnun comes to her grave and dies there.[7]

Translations and editions of the poem

The first translation of the work was a shortened poem in English. The translation was made by an English orientalist and translator James Atkinson.[8] It was published in 1836. Later, this translation was reissued several times (1894, 1915).[9][4]

The poem was translated into Russian by Eugene Bertels (a small prose translation from the poem), T. Forsch,[10] but the first full edition appeared with a poetic translation into Russian (completely) by Pavel Antokolsky. Rustam Aliyev carried out a complete philological prosaic translation of the work from Persian into Russian.[11]

The poem was translated into Azerbaijani by the poet Samad Vurgun in 1939.[12]

Poem’s analysis

This romantic poem belongs to the genre of "Udri" (otherwise "Odri"). The plot of the poems of this genre is simple and revolves around unrequited love. Heroes are semi-imaginary-semi-historical characters and their actions are similar to the actions of the characters of other romantic poems of this genre.[4]

The Arab-Bedouin legend was modified by Nizami. He also transferred the development of the plot to the urban environment and decorated the narrative with descriptions of nature as well.[4][10]

The poem was published in various countries in different versions of the text. However, the Iranian scientist Vahid Dastgerdi published a critical edition of the poem in 1934, compiling a text from 66 chapters and 3657 stanzas, dropping 1007 verses, defining them as later interpolations (distortions added to the text), although he admitted that some of them could have been added by Nizami himself.[4]

As in Arabic sources, Nizami refers to the poetic genius of Majnun at least 30 times. Majnun is presented as a poet who is able to compose dazzling verses in various poetic genres. Majnun reads love poems and elegies, which can be considered as psychological self-analysis, showing his disappointments and the reasons for his actions. In his commentary on Majnun's speech, the narrator always takes his side, which affects the reader's interpretation.[4]

In picturesque images, Majnun is portrayed as an emaciated ascetic. Nizami shows that the experience of a loving person and an ascetic is similar, except that the ascetic acts deliberately, while the lover suffers from the power of love. In the prologue and epilogue, Nizami gives advice to the reader about various topics such as the transience of life, death, humility, etc.[4]

Popular culture

Miniatures depicting the heroes of the poem "Layla and Majnun" were created by miniature artists from different cities, such as Tabriz and Herat. For instance, Aga Mirek, Mir Seid Ali and Muzaffar Ali created such miniatures.

An opera, Leyli and Majnun composed by the Azerbaijani composer Uzeyir Hajibayov, was premiered in 1908.[13][14]

Azerbaijani composer Gara Garayev wrote a symphonic poem, Layla and Majnun, first performed in Baku on September 29, 1947, at the solemn evening in honor of the 800th anniversary of Nizami Ganjavi, and the one-act ballet Leyli and Majnun based on the poem.[15]

There is a bas-relief depicting the heroes of the poem - Layla and Majnun, as a schoolgirl and a schoolboy performed on the pedestal of Nizami Ganjavi monument in Baku, which was established in 1949, by sculptor A. Khryunov and which was based on the sketches of the artist Gazanfar Halykov. This bas-relief is a part of Hermitage museum collection in Saint Petersburg.[16]

In 1960, the first Tajik ballet film called “Layla and Majnun” was shot based on the poem at the Tajikfilm studio.[17] A year later, the eponymous film based on the poem was shot at the film studio "Azerbaijanfilm" (the role of Majnun was performed by Nedar Shashik-ogly).[18]

Azerbaijani artist Mikayil Abdullayev made mosaic panels at the Nizami Ganjavi subway station of the Baku Metro depicting the heroes of the poem.[19]

Eric Clapton read this poem and thought of his unrequited, doomed love for Patty Boyd, the wife of George Harrison. It resulted in his song Layla.

Author Roshani Chokshi references the poem in her bestselling trilogy "The Gilded Wolves". Her character Séverin is referred to as "Majnun" by his love interest, Laila.

In 2022 the Tedeschi Trucks Band released a series of four albums under the title "I Am the Moon". The albums are inspired by the story of Layla and Majnun with a focus on Layla's perspective.[20]

See also

References

- ^ a b "Layla and Majnun". Archived from the original on 2019-10-18. Retrieved 2018-06-19.

- ^ Nizami Ganjavi and his Khamsa. Jeffrey Frank Jones.

- ^ "Layla and Majnun". www.lincolncenter.org. Archived from the original on 2018-06-19. Retrieved 2018-06-19.

- ^ a b c d e f g "LEYLI O MAJNUN". www.iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 2018-06-19.

- ^ "6.3 The Legend of Leyli and Majnun". www.azer.com. Retrieved 2018-06-19.

- ^ Parvaz, Sarvineh (2018-01-20). "The Legend of Leyli and Majnun - Welcome to Iran". Welcome to Iran. Retrieved 2018-06-19.

- ^ "The Story". Layla and Majnun. Retrieved 2018-06-19.

- ^ "Poem: From the Tale of "Laili and Majnun" by James Atkinson". poetrynook.com. Retrieved 2018-06-19.

- ^ Blois, Francois De (2004-08-02). Persian Literature - A Bio-Bibliographical Survey: Poetry of the Pre-Mongol Period. Routledge. ISBN 9781135467128.

- ^ a b Lornejad, Siavash; Doostzadeh, Ali (2012). ON THE MODERN POLITICIZATION OF THE PERSIAN POET NEZAMI GANJAVI. CCIS. ISBN 9789993069744.

- ^ "Translations of Layla and Majnun into Russian" (PDF).

- ^ Altstadt, Audrey (2016-06-23). The Politics of Culture in Soviet Azerbaijan, 1920-40. Routledge. ISBN 9781317245438.

- ^ "The First Eastern Opera "Leyli and Majnun"". Visions of Azerbaijan Magazine (in Russian). Retrieved 2018-06-19.

- ^ "Opera "Layla and Majnun" by Uzeyir Hajibeyov" (PDF).

- ^ Huseynova, Aida (2016-03-21). Music of Azerbaijan: From Mugham to Opera. Indiana University Press. ISBN 9780253019493.

- ^ "Layla and Majnun at School -". Retrieved 2018-06-19.

- ^ "The Virginal Love of Layla Majnun – Good Times". goodtimes.com.pk. Retrieved 2018-06-19.

- ^ "Leyli və Məcnun (1961)". azerikino.com. Retrieved 2018-06-19.

- ^ "Mikayil Abdullayev heritage".

- ^ "I Am The Moon". tedeschitrucksband.com.

Literature

- Layli and Majnun: Love, Madness and Mystic Longing, Dr. Ali Asghar Seyed-Gohrab, Brill Studies in Middle Eastern literature, Jun 2003, ISBN 90-04-12942-1.

- The Story of Layla and Majnun, by Nizami. Translated Dr. Rudolf. Gelpke in collaboration with E. Mattin and G. Hill, Omega Publications, 1966, ISBN 0-930872-52-5.