Languages of the Philippines

| Languages of the Philippines | |

|---|---|

| |

| Official | Filipino and English |

| National | Filipino[1] |

| Regional | |

| Vernacular | |

| Foreign | |

| Signed | Filipino Sign Language American Sign Language |

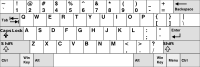

| Keyboard layout | |

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Culture of the Philippines |

|---|

|

| Society |

| Arts and Literature |

| History and Tradition |

| Symbols |

|

Philippines portal |

There are some 130 to 195 languages spoken in the Philippines, depending on the method of classification.[3][4][5][6] Almost all are Malayo-Polynesian languages native to the archipelago. A number of Spanish-influenced creole varieties generally called Chavacano along with some local varieties of Chinese[7][8][9] are also spoken in certain communities. The 1987 constitution designates Filipino, a standardized version of Tagalog, as the national language and an official language along with English. Filipino is regulated by Commission on the Filipino Language and serves as a lingua franca used by Filipinos of various ethnolinguistic backgrounds.[10]

Republic Act 11106 declares Filipino Sign Language or FSL as the country's official sign language and as the Philippine government's official language in communicating with the Filipino Deaf.[11]

While Filipino is used for communication across the country's diverse linguistic groups and in popular culture, the government operates mostly using English. Including second-language speakers, there are more speakers of Filipino than English in the Philippines.[12] The other regional languages are given official auxiliary status in their respective places according to the constitution but particular languages are not specified.[13] Some of these regional languages are also used in education.[2]

The indigenous scripts of the Philippines (such as the Kulitan, Tagbanwa and others) are used very little; instead, Philippine languages are today written in the Latin script because of the Spanish and American colonial experience. Baybayin, though generally not understood, is one of the most well-known of the Philippine indigenous scripts and is used mainly in artistic applications such as on current Philippine banknotes, where the word "Pilipino" is inscribed using the writing system. Additionally, the Arabic script is used in the Muslim areas in the southern Philippines.

Tagalog and Cebuano are the most commonly spoken native languages. Filipino and English are the official languages of the Philippines. The official languages were used as the main modes of instruction in schools, allowing mother tongues as auxiliary languages of instruction.[14] The Philippine Department of Education (DepEd) has put forth initiatives in using mother tongues as modes of instructions over the years.[15][16][17]

National and official languages

History

Spanish was the official language of the country for more than three centuries under Spanish colonial rule, and became the lingua franca of the Philippines in the 19th and early 20th centuries. In 1863, a Spanish decree introduced universal education, creating free public schooling in Spanish.[18] It was also the language of the Philippine Revolution, and the 1899 Malolos Constitution effectively proclaimed it as the official language of the First Philippine Republic.[19] National hero José Rizal wrote most of his works in Spanish. Following the American occupation of the Philippines and the imposition of English, the use of Spanish declined gradually. Spanish then declined rapidly because of the Japanese occupation in the 1940s.[20]

Under the U.S. occupation and civil regime, English began to be taught in schools. By 1901, public education used English as the medium of instruction. Around 600 educators (called "Thomasites") who arrived in that year aboard the USAT Thomas replaced the soldiers who also functioned as teachers. The 1935 Constitution added English as an official language alongside Spanish. A provision in this constitution also called for Congress to "take steps toward the development and adoption of a common national language based on one of the existing native languages." On November 12, 1937, the First National Assembly created the National Language Institute. President Manuel L. Quezón appointed native Waray speaker Jaime C. De Veyra to chair a committee of speakers of other regional languages. Their aim was to select a national language among the other regional languages. Ultimately, Tagalog was chosen as the base language on December 30, 1937, on the basis that it was the most widely spoken and developed local language.[21] Quezon himself was born and raised in Baler, Aurora, which is a native Tagalog-speaking area.

In 1939, President Manuel L. Quezón renamed the Tagalog language as Wikang Pambansa ("national language" in English translation).[22] The language was further renamed in 1959 as Pilipino by Secretary of Education José E. Romero. The 1973 constitution declared the Pilipino language to be co-official, along with English, and mandated the development of a national language, to be known as Filipino. In addition, Spanish regained its official status when President Ferdinand Marcos signed Presidential Decree No. 155, s. 1973.[23]

The 1987 Constitution under President Corazon Aquino declared Filipino to be the national language of the country. Filipino and English were named as the country's official languages, with the recognition of regional languages as having official auxiliary status in their respective regions (though not specifying any particular languages). Spanish and Arabic were to be promoted on an optional and voluntary basis.[24] Filipino also had the distinction of being a national language that was to be "developed and enriched on the basis of existing Philippine and other languages." Although not explicitly stated in the constitution, Filipino is in practice almost completely composed of the Tagalog language as spoken in the capital, Manila; however, organizations such as the University of the Philippines began publishing dictionaries such as the UP Diksyonaryong Filipino in which words from various Philippine languages were also included. The present constitution is also the first to give recognition to other regional languages.

Republic Act No. 7104, approved on August 14, 1991, by President Corazon Aquino, created the Commission on the Filipino Language, reporting directly to the President and tasked to undertake, coordinate and promote research for the development, propagation and preservation of Filipino and other Philippine languages.[25] On May 13, 1992, the commission issued Resolution 92–1, specifying that Filipino is the

...indigenous written and spoken language of Metro Manila and other urban centers in the Philippines used as the language of communication of ethnic groups.[26]

In 2013, President Noynoy Aquino's government launched the country's mother tongue-based multi-lingual education program for students in kindergarten to Grade 3, effectively reviving the usage and proliferation of various indigenous languages in the country.[27] The program also strengthened the Filipino language and English language learning capabilities of students.[28] In 2018, President Rodrigo Duterte signed Republic Act 11106, declaring Filipino Sign Language (FSL) as the country's official language for the Filipino deaf community.[29]

Usage

Filipino is a standardized version of Tagalog, spoken mainly in Metro Manila.[30] Both Filipino and English are used in government, education, print, broadcast media, and business, with third local languages often being used at the same time.[31] Filipino has borrowings from, among other languages, Spanish,[32] English,[33] Arabic,[34] Persian, Sanskrit,[35] Malay,[36] Chinese,[37][38] Japanese,[39] and Nahuatl.[40] Filipino is an official language of education, but less important than English as a language of publication (except in some domains, like comic books) and less important for academic-scientific-technological discourse. Filipino is used as a lingua franca in all regions of the Philippines as well as within overseas Filipino communities, and is the dominant language of the armed forces (except perhaps for the small part of the commissioned officer corps from wealthy or upper-middle-class families) and of a large part of the civil service, most of whom are non-Tagalogs.

There are different forms of diglossia that exist in the case of regional languages. Locals may use their mother tongue or the regional lingua franca to communicate amongst themselves, but sometimes switch to foreign languages when addressing outsiders. Another is the prevalence of code-switching to English when speaking in both their first language and Tagalog.

The Constitution of the Philippines provides for the use of the vernacular languages as official auxiliary languages in provinces where Filipino is not the lingua franca. Filipinos by and large are polyglots; in the case where the vernacular language is a regional language, Filipinos would speak in Filipino when speaking in formal situations while the regional languages are spoken in non-formal settings. This is evident in major urban areas outside Metro Manila like Camarines Norte in the Bikol-speaking area, and Davao in the Cebuano-speaking area. As of 2017, the case of Ilocano and Cebuano are becoming more of bilingualism than diglossia due to the publication of materials written in these languages.[citation needed] The diglossia is more evident in the case of other languages such as Pangasinan, Kapampangan, Bikol, Waray, Hiligaynon, Sambal, and Maranao, where the written variant of the language is becoming less and less popular to give way to the use of Filipino. Although Philippine laws consider some of these languages as "major languages" there is little, if any, support coming from the government to preserve these languages. This may be bound to change, however, given current policy trends.[41]

There still exists another type of diglossia, which is between the regional languages and the minority languages. Here, we label the regional languages as acrolects while the minority languages as the basilect. In this case, the minority language is spoken only in very intimate circles, like the family or the tribe one belongs to. Outside this circle, one would speak in the prevalent regional language, while maintaining an adequate command of Filipino for formal situations. Unlike the case of the regional languages, these minority languages are always in danger of becoming extinct because of speakers favoring the more prevalent regional language. Moreover, most of the users of these languages are illiterate[specify] and as expected, there is a chance that these languages will no longer be revived due to lack of written records.[citation needed]

In addition to Filipino and English, other languages have been proposed as additional nationwide languages. Among the most prominent proposals are Spanish[42][43] and Japanese.[44][45]

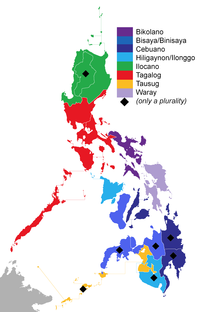

Regional languages

According to Ethnologue, a total of 182 native languages are spoken in the nation and four languages have been classified as extinct: Dicamay Agta, Katabaga, Tayabas Ayta and Villaviciosa Agta.[46] Except for English, Spanish, Chavacano and varieties of Chinese (Hokkien, Cantonese and Mandarin), all of the languages belong to the Malayo-Polynesian branch of the Austronesian language family.

The following are the four Philippine languages with more than five million native speakers:[47]

In addition, there are seven with between one and five million native speakers:

One or more of these is spoken natively by more than 90% of the population.

A Philippine language sub-family identified by Robert Blust includes languages of north Sulawesi and the Yami language of Taiwan, but excludes the Sama–Bajaw languages of the Tawi-Tawi islands, as well as a couple of North Bornean languages spoken in southern Palawan.

Eskayan is an artificial auxiliary language created as the embodiment of a Bohol nation in the aftermath of the Philippine–American War. It is used by about 500 people.

A theory that the Brahmic scripts of Sumatra, Sulawesi and the Philippines are descended from an early form of the Gujarati script was presented at the 2010 meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society.[48]

Mutual intelligibility

Philippine languages are often referred to by Filipinos as dialects, partly as a relic of the inaccurate vocabulary used in literature during the American period (1898–1946).[22] While there are indeed many hundreds of dialects in the Philippines, they represent variations of no fewer than 120 distinct languages, and many of these languages maintain greater differences than those between established European languages like French and Spanish.

The vast differences between the languages can be seen in the following translations of what has been asserted to be the Philippine national proverb:[49]

| Language | Translation |

|---|---|

| English | A person who does not look back at where they came from will not get to their destination. |

| Spanish | El que no mira hacia atrás de donde vino, no llegará a su destino. |

| Philippine Hokkien (Lán-nâng-ōe) | Hit-gé lâng ná kiâⁿ ná bô khòaⁿ kāi-kī ǎu-piah tùi só͘-chǎi tǐ lō͘, ě bô thang kàu lō͘.「彼个人那行那無看家己後壁對所在佇路,會無通到路。」 |

| Indonesian & Malaysian (Malay) | Seseorang yang tidak melihatbaliki asal-muasalnya takkan mungkin mencapai tujuannya. |

| Aklanon | Ro uwa' gatan-aw sa anang ginhalinan hay indî makaabut sa anang ginapaeangpan. |

| Asi (Bantoanon) | Kag tawong waya giruromroma it ida ginghalinan, indi makaabot sa ida apagtuan. |

| Bolinao | Si'ya a kai tanda' nin lumingap sa pangibwatan na, kai ya mirate' sa keen na. |

| Bontoc (Ifuntok) | Nan Adi mang ustsong sinan narpuwan na, adi untsan isnan umayan na. |

| Botolan | Hay ahe nin nanlek ha pinag-ibatan, ay ahe makarateng ha lalakwen. |

| Butuanon | Kadtong dilì kahibalo molingì sa iyáng gigikanan, dilì makaabot sa iyáng adtu-an. |

| West Miraya Bikol (Ligao) | Kan idî tatao magkiling sa inalian, idî makaabot sa papaidtuhan. |

| Buhinon Bikol (Buhi) | Yu di nikiling sa pinagalinan, dì makaantos sa pupuntahan. |

| Central Bikol (Canaman) | An dai tataong magsalingoy sa saiyang ginikanan, dai makakaabot sa padudumanan. |

| Gubatnon Bikol (Gubat) | An diri maaram mag-imud sa pinaghalian, diri makaabot sa pakakadtu-an. |

| East Miraya Bikol (Daraga) | Su indî tataw makarumdom nung ginitan, indî makaabot sa adunan. |

| East Miraya Bikol (Guinobatan) | Su indî tataw makarəmdəm nū ginítan, indi' makābot sa ādunan. |

| West Miraya Bikol (Oas) | Kan na taw na idî tataw maglinguy sa sanyang inalian, idi man maka abot sa sanyang paidtunan. |

| Rinconada Bikol (Iriga) | A dirī tattaoŋ maglīlî sa pinaŋgalinan, dirī makaaābot sa pig-iyānan. |

| Capiznon | Ang indî kabalo magbalikid sa iyá ginhalinan, indî makalab-ot sa iyá palakadtuan. |

| Cebuano Bohol (Binol-anon) | Sijá nga dì kahibawng molíngì sa ijáng gigikanan, dî gajúd makaabót sa ijáng padulngan. |

| Cebuano (Metro Cebu Variety) | Ang dì kahibáw molingis' iyáng gigikanan, dì gyud makaabots' iyáng padulngan. |

| Cebuano (Sialo-Carcar Standard) | Ang dilì kahibaló molingì sa iyahang gigikanan, dilì gayúd makaabót sa iyahang padulngan. |

| Chavacano Caviteño | Quien no ta bira cara na su origen no de incarsa na su destinación. |

| Chavacano Ternateño | Ay nung sabi mira i donde ya bini no di llega na destinación. |

| Chavacano Zamboangueño | El Quien no sabe vira el cara na su origen, nunca llega na su destinación. |

| Cuyonon | Ang ara agabalikid sa anang ing-alinan, indi enged maka-abot sa anang papakonan. |

| Ibanag | I tolay nga ari mallipay ta naggafuananna, ari makadde ta angayanna. |

| Ilokano | Ti tao nga saan na ammo tumaliaw iti naggapuanna ket saan nga makadanon iti papananna. |

| Itawis | Ya tolay nga mari mallipay tsa naggafuananna, mari makakandet tsa angayanna. |

| Hiligaynon (Ilonggo) | Ang indi kabalo magbalikid sang iya nga ginhalinan, indi makaabot sa iya nga pakadtuan. |

| Jama Mapun | Soysoy niya' pandoy ngantele' patulakan ne, niya' ta'abut katakkahan ne. |

| Kapampangan | Ing e byasang malikid king kayang penibatan, e ya miras king kayang pupuntalan. |

| Kabalian | Sija nga dili kahibayu mulingi sa ija gigikanan, dili makaabut sa ija pasingdan/paduyungan. |

| Kinaray-a | Ang indî kamaán magbalikid sa ana ginhalinan, indî makaabót sa ana paaragtunan. |

| Manobo (Obo) | Iddos minuvu no konnod kotuig nod loingoy to id pomonan din, konna mandad od poko-uma riyon tod undiyonnan din. |

| Maranao | So tao a di matao domingil ko poonan iyan na di niyan kakowa so singanin iyan. |

| Masbateño | An dilì maaram maglingì sa ginhalian, kay dilì makaabot sa kakadtuhan. |

| Pangasinan | Say toon agga onlingao ed pinanlapuan to, agga makasabi'd laen to. |

| Romblomanon (Ini) | Ang tawo nga bukon tigo mag lingig sa iya guinghalinan hay indi makasampot sa iya ning pagakadtoan. |

| Sambali | Hay kay tanda mamanomtom ha pinangibatan, kay immabot sa kakaon. |

| Sangil | Tao mata taya mabiling su pubuakengnge taya dumanta su kadam tangi. |

| Sinama | Ya Aa ga-i tau pa beleng ni awwal na, ga-i du sab makasong ni maksud na. |

| Surigaonon | Adtón dilì mahibayó molingì sa ija ing-gikanan, dilì gajód makaabót sa ija pasingdan. |

| Sorsoganon | An dirì mag-imud sa pinaghalian dirì makaabot sa kakadtuan. |

| Tagalog (Tayabas) | Ang hindi maalam lumingon sa pinaroonan ay hindi makakarating sa paroroonan. |

| Tagalog (Manila) | Ang hindi marunong lumingon sa pinanggalingan ay hindi makararating (makakarating) sa paroroonan. |

| Tausug | In di' maingat lumingi' pa bakas liyabayan niya, di' makasampay pa kadtuun niya. |

| Waray (Leyte) | An diri maaram lumingi ha tinikangan, diri maulpot ha kakadtoan. |

| Waray (Northern Samar) | An diri maaram lumingi sa tinikangan, diri maabot sa kakadtuan. |

| Yakan | Mang gey matau mamayam si bakas palaihan nen, gey tekka si papilihan nen. |

Dialectal variation

The amount of dialectal variation varies from language to language. Languages like Tagalog, Kapampangan and Pangasinan are known to have very moderate dialectal variation.

For the languages of the Bicol Region, however, there is great dialectal variation. There are cities and towns which have their own dialects and varieties. Below is the sentence "Were you there at the market for a long time?" translated into certain varieties of Bikol. The translation is followed by dialect and corresponding language, and a city/town in Bicol where they are spoken. The final translation is in Tagalog.

- Haloy ka duman sa saod? (Standard Coastal Bikol, a dialect of Central Bikol; Canaman, Camarines Sur)

- Aloy ka duman sa saod? (Magarao, a variety of Coastal Bikol; Magarao, Camarines Sur)

- Naawat ka duman sa saod? (Southern Catanduanes Bikol or Virac Bikol, a dialect of Coastal Bikol; Virac, Catanduanes)

- Naəban ikā sadtō sāran? (Rinconada Bikol; Iriga City)

- Nauban ikā sadtō sāran? (Rinconada Bikol; Nabua, Camarines Sur)

- Uban ika adto sa saod? (Libon, Albay Bikol; Libon, Albay)

- Naëǧëy ika adto sa saran? (Buhinon, Albay Bikol; Buhi, Camarines Sur)

- Ëlëy ka idto sa sëd? (West Miraya Bikol, Albay Bikol; Oas, Albay)

- Na-alõy ika idto sa sâran/merkado? (West Miraya Bikol, Albay Bikol; Polangui, Albay)

- Naëlay ka idto sa saran? (East Miraya Bikol, Albay Bikol; Guinobatan, Albay)

- Naulay ka didto sa saran? (East Miraya Bikol, Albay Bikol; Daraga, Albay)

- Dugay ka didto sa merkado? (Ticao, Masbateño; Monreal, Masbate)

- Awat ka didto sa plasa? (Gubat, Southern Sorsogon; Gubat, Sorsogon)

- Awát ka didto sa rilansi? (Bulan, Southern Sorsogon; Bulan, Sorsogon)

- Matagál ka na ba roón sa palengke? (Tagalog)

Comparison chart

Below is a chart of Philippine languages. While there have been disagreements on which should be classified as a language and which should be classified as a dialect, the chart shows that most have similarities, yet are not mutually comprehensible. These languages are arranged according to the regions where they are natively spoken (from north to south, then east to west).

| English | one | two | three | four | person | house | dog | coconut | day | new | we (inclusive) | what | and |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ivatan | asa | dadowa | tatdo | apat | tao | vahay | chito | niyoy | araw | va-yo | yaten | ango | kan |

| Ilokano | maysa | dua | tallo | uppat | tao | balay | aso | inyog | aldaw | baro | datayo | ania | ken |

| Ifuntok | əsang | tswa | Tulo | əpat | tacu | Afong | aso | inyog | acəw | falu | tsattaku | ngag | ya |

| Ibanag | tadday | dua | tallu | appa' | tolay | balay | kitu | inniuk | aggaw | bagu | sittam | anni | anne |

| Gaddang | tata | addwa | tallo | appat | tolay | balay | atu | ayog | aw | bawu | ikkanetem | sanenay | e |

| Pangasinan | sakey | duara | talora | apatira | too | abong | aso | niyog | agew | balo | sikatayo | anto | tan/et |

| Kapampangan | métung | adwá | atlú | ápat | taú | bale | ásu | ngungút | aldó | bayu | ikátamú | nanú | ampong/at |

| Sambal | saya | rwa | tolo | àpat | tawu | balè | aso | ungut | awro | bâ-yo | udèng | ani | tan |

| Tagalog | isá | dalawá | tatló | apat | tao | bahay | aso | niyóg | araw | bago | tayo / kamí (exclusive) | anó | at |

| Coastal Bikol | saro | duwa | tulo | apat | tawo | harong | ido | niyog | aldaw | ba-go | kita | ano | asin, buda |

| Rinconada Bikol | əsad | darwā | tolō | əpat | tawō | baləy | ayam | noyog | aldəw | bāgo | kitā | onō | ag, sagkəd, sakâ |

| West Miraya Bikol | sad | duwa | tulo | upat | taw | balõy | ayam | nuyog | aldõw | bâgo | kita, sato | uno | dangan, mî, saka |

| East Miraya Bikol | usad | duw | tulo | upat | taw | balay | ayam | nuyog | aldaw | bâgo | kita, satun, kami | uno | dangan, mî, saka, kina |

| Masbateño | usád | duhá | tuló | upát | tawo | baláy | idô | buko, lubí | aldaw | bag-o | kita, kamí, amon | nano | kag |

| Romblomanon | isá | duhá | tuyó | upát | tawo | bayay | ayam | niyóg | adlaw | bag-o | kitá, aton | ano | kag |

| Bantoanon | usa | ruha | tuyo | upat | tawo | bayay | iro | nidog | adlaw | bag-o | kita, ato | ni-o | ag |

| Onhan | isya | darwa | tatlo | apat | tawo | balay | ayam | niyog | adlaw | bag-o | kita, taton | ano | ag |

| Kinaray-a | sara | darwa | tatlo | apat | taho | balay | ayam | niyog | adlaw | bag-o | kita, taten | ano, iwan | kag |

| Hiligaynon | isá | duhá | tatló | apat | tawo | baláy | idô | lubí | adlaw | bag-o | kitá | anó | kag |

| Cebuano | usá | duhá | tuló | upát | tawo | baláy | irô | lubí | adlaw | bag-o | kitá | unsa | ug |

| Kabalian | usá | duhá | tuyó | upát | tawo | bayáy | idô | lubí | adlaw | bag-o | kitá | unó | ug |

| Waray | usá | duhá | tuló | upát | tawo | baláy | ayam | lubí | adlaw | bag-o | kitá | ano | ngan, ug |

| Surigaonon | isá | duhá | tuyó | upát | tao | bayáy | idû | niyóg | adlaw | bag-o | kamí | unú | sanan |

| Maguindanao | isa | duwa | telu | pat | taw | walay | aso | niyug | gay | bagu | tanu | ngin | engu |

| T'boli | sotu | lewu | tlu | fat | tau | gunu | ohu | lefo | kdaw | lomi | tekuy | tedu | ne |

| Tausug | hambuuk | duwa | tu | upat | tau | bay | iru' | niyug | adlaw | ba-gu | kitaniyu | unu | iban |

| Chavacano | uno | dos | tres | cuatro | gente | casa | perro | coco | dia | nuevo | Zamboangueño: nosotros/kita; Bahra: mijotros/motros; Caviteño: nisos |

cosá/ qué | y/e |

| Spanish | uno | dos | tres | cuatro | persona | casa | perro | coco | día | nuevo | nosotros | que | y/e |

| Philippine Hokkien | it / tsi̍t (一) | dī (二) / nňg (兩) | saⁿ (三) | sì (四) | lâng (儂) | tshù (厝) | káu (狗) | iâ (椰) / iâ-á (椰仔) | di̍t (日) | sin (新) | lán (咱) | siám-mih (啥物) | kap (佮) / ka̍h (交) |

There is a language spoken by the Tao people (also known as Yami) of Orchid Island of Taiwan which is not included in the language of the Philippines. Their language, Tao (or Yami) is part of the Batanic languages which includes Ivatan, Babuyan, and Itbayat of the Batanes.

| English | one | two | three | four | person | house | dog | coconut | day | new | we | what |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tao | ása | dóa (raroa) | tílo (tatlo) | ápat | tao | vahay | gara | ngata | araw | vayo | tata | vela |

| Ivatan | asa | dadowa | tatdo | apat | tao | vahay | chito | niyoy / gata | araw | va-yo | yaten | ango |

Native speakers

Below are the numbers of Filipinos who speak the following 20 languages as their native languages based on the 2020 Census of Population and Housing[47] by the Philippine Statistics Authority. The number of speakers of each language is calculated from the reported number of households by assuming an average household size of 4.1 persons as of 2020.[50]

Native languages in the Philippines

| Language | ISO 639–3 | Native speakers |

|---|---|---|

| Tagalog | tl | 43,142,279 |

| Cebuano/Bisaya/Binisaya/Boholano | ceb | 25,584,734 |

| Hiligaynon | hil | 7,927,399 |

| Ilocano | ilo | 7,639,977 |

| Bicolano | bik | 4,237,174 |

| Waray | war | 2,864,855 |

| Kapampangan | pam | 2,622,717 |

| Maguindanao | mdh | 1,496,631 |

| Pangasinan | pag | 1,372,512 |

| Tausug | tsg | 1,129,419 |

| Maranao | mrw | 1,123,851 |

| Karay-a | krj | 601,987 |

| Aklanon/Bukidnon/Binukid-Akeanon | akl, mlz | 545,796 |

| Masbateño | msb | 524,341 |

| Surigaonon | sgd | 466,022 |

| Zamboangueño | cbk | 428,327 |

| Kankanaey | kne | 291,125 |

| Sama/Samal | ssb, sml, sse, slm | 274,602 |

| B'laan/Blaan | bpr, bps | 272,539 |

| Ibanag | ibg | 257,628 |

| Iranon/Iranun/Iraynon | ilp | 230,113 |

By households

Below are the country's top ten languages by the number of households in which they are spoken, according to the Philippine Statistics Authority. There are a total of 26,388,654 households in the country.[47]

| Language | Number of households |

% |

|---|---|---|

| Tagalog | 10,522,507 | 39.9 |

| Bisaya/Binisaya | 4,214,122 | 16.0 |

| Hiligaynon/Ilonggo | 1,933,512 | 7.3 |

| Ilocano | 1,863,409 | 7.1 |

| Cebuano | 1,716,080 | 6.5 |

| Bikol | 1,033,457 | 3.9 |

| Waray | 698,745 | 2.6 |

| Kapampangan | 639,687 | 2.4 |

| Maguindanao | 365,032 | 1.4 |

| Pangasinan/Pangasinense | 334,759 | 1.3 |

| Others^ | ~2,950,000 | 11.2 |

^Boholano, Tausug/Bahasa Sug, Maranao, Karay-a/Kinaray-a, Bukidnon/Binukid-Akeanon/Aklanon, Masbateño/ Masbatenon, Surigaonon, and Zamboagueño-Chavacano

Negrito languages

Language vitality

2010 UNESCO designation

Endangered and extinct languages in the Philippines are based on the 3rd world volume released by UNESCO in 2010.

Degree of endangerment (UNESCO standard)

- Safe: language is spoken by all generations; intergenerational transmission is uninterrupted.

- Vulnerable: most children speak the language, but it may be restricted to certain domains (e.g., home).

- Definitely endangered: children no longer learn the language as mother tongue in the home.

- Severely endangered: language is spoken by grandparents and older generations; while the parent generation may understand it, they do not speak it to children or among themselves.

- Critically endangered: the youngest speakers are grandparents and older, and they speak the language partially and infrequently.

- Extinct: there are no speakers left. These languages are included in the Atlas if presumably extinct since the 1950s.

| Language | Speakers (in 2000) |

Province | Coordinates | ISO 639–3 code |

Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vulnerable languages | |||||

| Central Cagayan Agta | 779 | Cagayan | 17°59′21″N 121°51′37″E / 17.9891°N 121.8603°E | agt | UNESCO 2000 |

| Dupaninan Agta | 1400 | Cagayan | 17°58′06″N 122°02′10″E / 17.9682°N 122.0361°E | duo | David Bradley (UNESCO 2000) |

| Definitely endangered | |||||

| Bataan Agta | 500 | Bataan | 14°25′57″N 120°28′44″E / 14.4324°N 120.4788°E | ayt | David Bradley (UNESCO 2000) |

| Mt. Iraya Agta | 150 | Camarines Sur | 13°27′32″N 123°32′48″E / 13.459°N 123.5467°E | atl | David Bradley (UNESCO 2000) |

| Batak | 200 | Palawan | 10°06′29″N 119°00′00″E / 10.1081°N 119°E | bya | David Bradley (UNESCO 2000) |

| Severely endangered | |||||

| Faire Atta | 300 | Ilocos Norte | 18°01′37″N 120°29′34″E / 18.027°N 120.4929°E | azt | David Bradley (UNESCO 2000) |

| Northern Alta | 200 | Aurora | 15°42′58″N 121°24′31″E / 15.7162°N 121.4085°E | agn | David Bradley (UNESCO 2000) |

| Camarines Norte Agta | 150 | Camarines Norte | 14°00′49″N 122°53′14″E / 14.0135°N 122.8873°E | abd | David Bradley (UNESCO 2000) |

| Critically endangered | |||||

| Alabat Island Agta | 30 | Quezon | 14°07′15″N 122°01′42″E / 14.1209°N 122.0282°E | dul | David Bradley (UNESCO 2000) |

| Isarog Agta | 5 | Camarines Sur | 13°40′50″N 123°22′50″E / 13.6805°N 123.3805°E | agk | David Bradley (UNESCO 2000) |

| Southern Ayta (Sorsogon Ayta) | 150 | Sorsogon | 13°01′37″N 124°09′18″E / 13.027°N 124.1549°E | ays | David Bradley (UNESCO 2000) |

| Extinct | |||||

| Dicamay Agta (Dumagat, Dicamay Dumagat) |

0 | Isabela | 16°41′59″N 122°01′00″E / 16.6998°N 122.0167°E | duy | David Bradley (UNESCO 2000) |

| Arta | 0 | near Isabela-Quirino Border | 16°25′21″N 121°42′15″E / 16.4225°N 121.7042°E | atz | David Bradley (UNESCO 2000) |

| Katabaga | 0 | Quezon | 13°26′12″N 122°33′25″E / 13.4366°N 122.5569°E | ktq | David Bradley (UNESCO 2000) |

| Ata | 0 | Negros Oriental | 9°36′29″N 122°54′56″E / 9.6081°N 122.9155°E | atm | David Bradley (UNESCO 2000) |

2014 North Dakota study

In a separate study by Thomas N. Headland, the Summer Institute of Linguistics in Dallas, and the University of North Dakota called Thirty Endangered Languages in the Philippines, the Philippines has 32 endangered languages, but 2 of the listed languages in the study are written with 0 speakers, noting that they are extinct or probably extinct. All of the listed languages are Negrito languages, the oldest languages in the Philippines.[51]

| Language | General location of speakers[51] |

Population of speakers in the 1990s[51] |

Bibliographic source[51] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Batak | Palawan Island | 386 | Elder 1987 |

| Mamanwa | Mindoro Island | 1000 | Grimes 2000 |

| Ati | Northern Panay Island | 30 | Pennoyer 1987:4 |

| Ati | Southern Panay Island | 900 | Pennoyer 1987:4 |

| Ata | Negros Island | 450 | Cadelina 1980:96 |

| Ata | Mabinay, Negros Oriental | 25 | Grimes 2000 |

| Atta | Pamplona, western Cagayan | 1000 | Grimes 2000 |

| Atta | Faire-Rizal, western Cagayan | 400 | Grimes 2000 |

| Atta | Pudtol, Kalinga-Apayao | 100 | Grimes 2000 |

| Ayta | Sorsogon | 40 | Grimes 2000 |

| Agta (extinct, unverified) | Villaviciosa, Abra | 0 | Grimes 2000; Reid, per. com. 2001 |

| Abenlen | Tarlac | 6000 | K. Storck SIL files |

| Mag-anchi | Zambales Tarlac, Pampanga | 4166 | K. Storck SIL files |

| Mag-indi | Zambales, Pampanga | 3450 | K. Storck SIL files |

| Ambala | Zambales, Pampanga, Bataan | 1654 | K. Storck SIL files |

| Magbeken | Bataan | 381 | K. Storck SIL files |

| Agta | Isarog, Camarines Sur (noted as nearly extinct) | 1000 | Grimes 2000 |

| Agta | Mt. Iraya & Lake Buhi east, Camarines Sur (has 4 close dialects) | 200 | Grimes 2000 |

| Agta | Mt. Iriga & Lake Buhi west, Camarines Sur | 1500 | Grimes 2000 |

| Agta | Camarines Norte | 200 | Grimes 2000 |

| Agta | Alabat Island, southern Quezon | 50 | Grimes 2000 |

| Agta | Umirey, Quezon (with 3 close dialects) | 3000 | T. MacLeod SIL files |

| Agta | Casiguran, northern Aurora | 609 | Headland 1989 |

| Agta | Maddela, Quirino | 300 | Headland field notes |

| Agta | Palanan & Divilacan, Isabela | 856 | Rai 1990: 176 |

| Agta | San Mariano-Sisabungan, Isabela | 377 | Rai 1990: 176 |

| Agta (noted as recently extinct) | Dicamay, Jones, Isabela | 0 | Headland field notes, and Grimes 2000 |

| Arta | Aglipay, Quirino | 11 (30 in 1977) | Headland field notes, and Reid 1994:40 |

| Alta | Northern Aurora | 250 | Reid, per. comm. |

| Alta | Northern Quezon | 400 | Reid, per. comm. |

| Agta | eastern Cagayan, Supaninam (several close dialects) | 1200 | T. Nickell 1985:119 |

| Agta | central Cagayan | 800 | Mayfield 1987:vii-viii; Grimes 2000 |

Proposals to conserve Philippine languages

There have been numerous proposals to conserve the many languages of the Philippines. According to the Komisyon ng Wikang Filipino, there are 135 ethnolinguistic groups in the country, each having their own distinct Philippine language.

Among the proposals include (1) "establishing a dictionary & sentence construction manual" for each of the 135 living languages in the country, (2) "video documentation" of all Philippine languages, (3) "revival of the ancient scripts of the Philippines" where each ethnic group's own script shall be revived and used in schools along with the currently-used Roman script in communities where those script/s used to be known, (4) "teaching of ethnic mother languages first" in homes and schools before the teaching of Filipino and foreign languages (English, Spanish and Arabic), and (5) "using the ethnic mother language and script first in public signs" followed by Filipino and foreign languages (English, Spanish and Arabic) and scripts, for example, using Cebuano first followed by Filipino and English underneath the sign.

Currently, only the fourth proposal has been made by the national government of the Philippines.[52] A National Script bill has been filed in Congress in support of the third and fifth proposal, however, the bill only mandates the usage of the ancient script compatible with the national language, which is Filipino.[53]

Major immigrant languages

Arabic

Arabic is used by some Filipino Muslims in both a liturgical and instructional capacity since the arrival of Islam and establishment of several Sultanates in the 14th century. Along with Malay, Arabic was the lingua franca of the Malay Archipelago among Muslim traders and the Malay aristocracy.[citation needed]

The 1987 Constitution mandates that Arabic (along with Spanish) is to be promoted on an optional and voluntary basis. As of 2015 Arabic is taught for free and is promoted in some Islamic centres predominantly in the southernmost parts of Philippines. It is used primarily in religious activities and education (such as in a madrasa or Islamic school) and rarely for official events or daily conversation. In this respect, its function and use is somewhat like the traditional roles of Latin and Spanish in Filipino Catholicism vis-à-vis other currently spoken languages.

Islamic schools in Mindanao teach Modern Standard Arabic in their curriculum.[54]

English

The first significant exposure of Filipinos to the English language occurred in 1762 when the British invaded Manila during the Seven Years' War, but this was a brief episode that had no lasting influence. English later became more important and widespread during American rule between 1898 and 1946, and remains an official language of the Philippines.

On August 22, 2007, three Malolos City regional trial courts in Bulacan decided to use Filipino, instead of English, in order to promote the national language. Twelve stenographers from Branches 6, 80 and 81, as model courts, had undergone training at Marcelo H. del Pilar College of Law of Bulacan State University College of Law following a directive from the Supreme Court of the Philippines. De la Rama said it was the dream of former Chief Justice Reynato Puno to implement the program in other areas such as Laguna, Cavite, Quezón, Nueva Écija, Batangas, Rizal, and Metro Manila.[55]

English is used in official documents of business, government, the legal system, medicine, the sciences and as a medium of instruction. Filipinos prefer textbooks for subjects like calculus, physics, chemistry, biology, etc., written in English rather than Filipino.[dubious – discuss] However, the topics are usually taught, even in colleges, in Tagalog or the local language. By way of contrast, native languages are often heard in colloquial and domestic settings, spoken mostly with family and friends. The use of English attempts to give an air of formality, given its use in school, government and various ceremonies.[citation needed] A percentage of the media such as cable television and newspapers are also in English; major television networks such as ABS-CBN and GMA and all AM radio stations broadcast primarily in Filipino, as well as government-run stations like PTV and the Philippine Broadcasting Service. However, a 2009 article by a UNICEF worker reported that the level of spoken English language in the Philippines was poor. The article reported that aspiring Filipino teachers score the lowest in English out of all of the subjects on their licensing exams.[56]

A large influx of English (American English) words have been assimilated into Tagalog and the other native languages called Taglish or Bislish. There is a debate, however, on whether there is diglossia or bilingualism, between Filipino and English. Filipino is also used both in formal and informal situations. Though the masses would prefer to speak in Filipino, government officials tend to speak in English when performing government functions.[according to whom?] There is still resistance to the use of Filipino in courts and the drafting of national statutes.

In parts of Mindanao, English and Tagalog blend with Cebuano to form "Davao Tagalog".[57]

Hokkien

Diplomatic ties with the Ming dynasty among some established states or kingdoms in Luzon and direct interactions and trade overall within the archipelago as a whole may go as far back as the early 10th century during the Song dynasty. Mandarin Chinese is the medium of instruction and subject matter being taught for Chinese class in Chinese schools in the Philippines. However, the Lan-nang-ue variant of Hokkien Chinese is the majority household and heritage language of the Chinese Filipinos who, for generations, mostly trace roots from Southern Fujian province in China. Other varieties of Chinese such as Yue Chinese (especially Taishanese or Cantonese), Teochew, and Hakka are spoken among a minority of Chinese Filipinos whose ancestral roots trace all the way back from the Guangdong or Guangxi provinces of Southern China. Most Chinese Filipinos raised in the Philippines, especially those of families of who have lived in the Philippines for multiple generations, are typically able and usually primarily speak Philippine English, Tagalog or other regional Philippine languages (e.g., Cebuano, Hiligaynon, Ilocano, etc.), or the code-switching or code-mixing of these such as Taglish or Bislish, but Philippine Hokkien is typically or occasionally used within Chinese Filipino households privately amongst family or acts a heritage language among descendants of such. Hokaglish is the code-switching equivalent of the above languages.

As with Spanish, many native languages have co-opted numerous loanwords from Chinese, in particular words that refer to cuisine, household objects, and Philippine kinship terminology.

Japanese

The Japanese first came to the Philippines around the 11th century CE, the first country they emigrated to, as well as in waves from the 15th century (as depicted in the Boxer Codex) 17th century, late 19th century, 1900s, 1930s, and the 1940s.[58][59][60][61][62] There is a small Japanese community and a school for Japanese in Metro Manila due to the number of Japanese companies. Also there is a large community of Japanese and Japanese descendants in Laguna province, Baguio, and in the Davao Region.[citation needed] Davao City is a home to a large population of Japanese descendants. Japanese laborers were hired by American companies like the National Fiber Company (NAFCO) in the first decades of the 20th century to work in abaca plantations. Japanese were known for their hard work and industry. During World War II to present, Japanese schools are present in Davao City, such as Philippine Nikkei Jin Kai International School (PNJK IS).

Korean

Korean is mainly spoken by the expatriates from South Korea and people born in the Philippines with Korean ancestry. The Korean language has been added under the Department of Education (DepEd) Special Program in Foreign Language (SPFL) curriculum, together with Spanish, French, German, Chinese, and Japanese.[63]

Malay

Malay is spoken as a second language by a minority of the Tausug, Sama-Bajau, and Yakan peoples in the southernmost parts of the Philippines, from Zamboanga down to Tawi-Tawi.[citation needed] It is also spoken as a daily language by the Indonesians and Malaysians who have settled, or do business in the Philippines. It is also spoken in southern Palawan to some extent. It is not spoken among the Maranao and Maguindanao peoples. Brunei, Malaysia, Indonesia and the southern Philippines are largely Islamic and the liturgical language of Islam is Arabic, but the vast majority of Muslims in the Philippines have little practical knowledge of Arabic beyond limited religious terminology.

The Malay language, a Malayo-Polynesian language alongside the Philippine languages, has had an immense influence on many of the languages of the Philippines. This is because Old Malay used to be the lingua franca throughout the archipelago, a good example of this is Magellan's translator Enrique using Malay to converse with the native Sugbuanon (Cebuano) during this time period.

An example of Old Malay spoken in Philippine history can be seen in the language of the 10th century Laguna Copperplate Inscription.

When the Spanish had first arrived in the Philippines in the 16th century, Old Malay was spoken among the aristocracy.

It is believed that Ferdinand Magellan's slave Enrique of Malacca could converse with the local leaders in Cebu Island, confirming to Magellan his arrival in Southeast Asia.

Today, Indonesian is taught as a foreign language in the Department of Linguistics and Asian Languages in the University of the Philippines. Also, the Indonesian School in Davao City teaches the language to preserve the culture of Indonesian immigrants there. The Indonesian Embassy in Manila also offers occasional classes for Filipinos and foreigners.

Since 2013, the Indonesian Embassy in the Philippines has given basic Indonesian language training to members of the Armed Forces of the Philippines.[64]

In an interview, Department of Education Secretary Armin Luistro[36] said that the country's government should promote Indonesian and Malaysian, which are both related to Filipino and other Philippine languages. Thus, the possibility of offering it as an optional subject in public schools is being studied.

South Asian languages

Since pre-Spanish times, there have been small Indian communities in the Philippines. Indians tend to be able to speak Tagalog and the other native languages, and are often fluent in English. Among themselves, Sindhi and Punjabi are used. Urdu is spoken among the Pakistani community. Only few South Asians, such as Pakistani, as well as the recent newcomers like speakers of Tamil, Nepali and Marathi retain their own respective languages.[59][65][66][67][68][69]

Spanish

Spanish was introduced in the islands after 1565, when the Spanish conquistador Miguel López de Legazpi set sail from Mexico and founded the first Spanish settlement on Cebú. Though its usage is not as widespread as before, Spanish has had a significant influence in the various local Philippine languages such as providing numerous loan words.[56] Several Spanish-based creole language varieties collectively known as Chabacano have also emerged. The current 1987 constitution makes mention of Spanish in which it provides that Spanish (along with Arabic) is to be promoted on an optional and voluntary basis.

In 1593, the first printing press in the Philippine islands was founded and it released the first (albeit polyglot) book, the Doctrina Christiana that same year. In the 17th century, Spanish religious orders founded the first universities in the Philippines, some of which are considered the oldest in Asia. During colonial rule through Mexico, Spanish was the language of education, trade, politics, and religion, and by the 19th century, became the colony's lingua franca although it was mainly used by the educated Filipinos.[70] In 1863, a Spanish decree introduced a system of public education, creating free public schooling in Spanish. In the 1890s, the Philippines had a prominent group of Spanish-speaking scholars called the Ilustrados, such as José Rizal. Some of these scholars participated in the Philippine Revolution and later in the struggle against American occupation. Both the Malolos Constitution and the Lupang Hinirang (national anthem) were written in Spanish.

Under U.S. rule, the English language began to be promoted instead of Spanish. The use of Spanish began to decline as a result of the introduction of English into the public schools as a language of instruction.[18] The 1935 constitution establishing the Philippine Commonwealth designated both English and Spanish as official languages. The 1950 census stated that Filipinos who spoke Spanish as a first or second language made up only 6% of the population. In 1990, the census reported that the number had dwindled to just 2,500 native speakers. A 2020 estimate indicated that about 400,000 Filipinos (less than 0.5% of the population) have working knowledge of the language.[71]

Spanish briefly lost its status as an official language upon promulgation of the 1973 constitution but regained official status two months later when President Marcos signed Presidential Decree No. 155.[23] In the 1987 constitution, Spanish is designated as an "optional and voluntary language" but does not mention it as an "official language". Spanish was dropped as a college requirement during Corazón Aquino's administration. Former president Gloria Macapagal Arroyo, a third-language Spanish speaker, introduced legislation to re-establish the instruction of Spanish in 2009 in the state education system. Today, the language is still spoken by Filipino-Spanish mestizos and Spanish families who are mainly concentrated in Metro Manila, Iloilo and Cebu. It remains an optional subject in some academic institutions, such as the University of Santo Tomás in Manila and the University of San Carlos in Cebu.

Up until recently, many historical documents, land titles, and works of literature were written in Spanish and not translated into Filipino languages or English. Spanish, through colonization has contributed the largest number of loanwords and expressions in Tagalog, Cebuano, and other Philippine languages.[72] The Academia Filipina de la Lengua Española (Philippine Academy of the Spanish Language), established in 1924, is a founding member of the Association of Academies of the Spanish Language; an association of the various Spanish academies of the world which cooperate in the standardizing and promotion of the Spanish language. Among its past and present academics are former President Arroyo, former Foreign Affairs Secretary Alberto Romulo, and Archbishop of Cebú Cardinal Ricardo Vidal.

Spanish creoles

There are several Spanish-based creole languages in the Philippines, collectively called Chavacano. These may be split into two major geographical groups:

- In Luzon:

- Caviteño (Chabacano de Cavite), spoken in Cavite City, Cavite.

- Ternateño (Chabacano de Bahra), spoken in Ternate, Cavite.

- Ermitaño (Chabacano de Ermita), formerly spoken in Ermita, Manila but is now extinct. The last reported speakers were a woman and her grandson during the 1980s and 1990s.

- In Mindanao:

- Zamboangueño Chavacano (Chabacano de Zamboanga / Zamboangueño Chavacano), spoken in Zamboanga City, Zamboanga Sibugay, Zamboanga del Sur, Zamboanga del Norte, Basilan, Sulu, Tawi-Tawi and Semporna, Sabah, Malaysia (360,000 native speakers-Zamboanga City alone as per 2000 census, making it the most spoken form and known form of Chavacano)

- Cotabateño (Chabacano de Cotabato), spoken in Cotabato

- Davaoeño Abakay (Chabacano de Davao), spoken in Davao City

See also

- Filipino alphabet

- Filipino orthography

- Philippine languages

- List of English words of Philippine origin

References

Notes

- ^ Constitution of the Republic of the Philippines, Article XIV, Section 7

- ^ a b "DepEd adds 7 languages to mother tongue-based education for Kinder to Grade 3". GMA News Online. July 13, 2013. Retrieved August 6, 2018.

- ^ "Philippines". Ethnologue. Retrieved September 28, 2017.

- ^ McFarland, C.D. (1994). "Subgrouping and Number of Philippine Languages". Philippine Journal of Linguistics. 25 (1–2): 75–84. ISSN 0048-3796.

- ^ The Komisyon sa Wikang Filipino enumerated 134 Philippine languages and 1 national language (Filipino) present in the country through its Atlas Filipinas map published in 2016.

- ^ "What languages are spoken in the Philippines?". www.futurelearn.com. Future Learn. July 11, 2022.

- ^ Tsai, Hui-Ming 蔡惠名 (2017). Fēilǜbīn zán rén huà (Lán-lâng-uē) yánjiū 菲律賓咱人話(Lán-lâng-uē)研究 [A Study of Philippine Hokkien Language] (PhD thesis) (in Chinese). National Taiwan Normal University.

- ^ Wong Gonzales, Wilkinson Daniel (May 2016). "Exploring trilingual code-switching: The case of 'Hokaglish' (PDF Download Available)". Retrieved October 24, 2016 – via ResearchGate.

- ^ Palanca, Ellen H. (2002). "A Comparative Study of Chinese Education in the Philippines and Malaysia*" (PDF). Asian Studies. 38 (2): 1 – via Asian Studies: Journal of Critical Perspectives on Asia.

- ^ Filipino, not English, is the country’s lingua franca, Inquirer, Feb 27, 2014

- ^ "[Republic Act No. 11106] An Act Declaring the Filipino Sign Language as the National Sign Language of the Filipino Deaf and the Official Sign Language of Government in All Transactions Involving the Deaf, and Mandating Its Use in Schools, Broadcast Media, and Workplaces" (PDF). Official Gazette. Government of the Philippines. October 30, 2018.

- ^ Eberhard, David M.; Gary F. Simons; Charles D. Fennig, eds. (2021). "Philippines". Ethnologue: Languages of the World (Twenty-fourth ed.). Dallas, Texas: SIL International.

- ^ The regional languages are the auxiliary official languages in the regions and shall serve as auxiliary media of instruction therein... Article XIV Section 7.

- ^ "DepEd Order No. 60, 2008" (PDF). Republic of the Philippines. August 27, 2008.

- ^ "DepEd Order No. 74, 2009" (PDF). Republic of the Philippines. July 14, 2009.

- ^ "DepEd Curriculum Guide 2013" (PDF). Republic of the Philippines.

- ^ "DepEd open to more dialogue on improvement of MTB-MLE implementation". DepEd.

- ^ a b "Philippines – Education". CountryStudies.us. Retrieved March 15, 2015.

- ^ Article 93 of the Malolos Constitution reads, "Art. 93. The use of languages spoken in the Philippines shall be optional. This use cannot be regulated except by virtue of law, and solely for acts of public authority and in the courts. For these acts the Spanish language will be used in the meantime."

- ^ "America's shameful rapprochement to the Franco dictatorship". October 23, 2018.

- ^ Manuel L. Quezon (December 1937). "Speech of His Excellency, Manuel L. Quezón, President of the Philippines on Filipino national language" (PDF). p. 4. Retrieved January 14, 2009.

- ^ a b Gonzalez, Andrew (1998). "The Language Planning Situation in the Philippines" (PDF). Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development. 19 (5, 6): 487–525. doi:10.1080/01434639808666365. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 16, 2007. Retrieved March 24, 2007.

- ^ a b "Presidential Decree No. 155 : Philippine Laws, Statutes and Codes". Chan Robles Virtual Law Library. Retrieved March 15, 2015.

- ^ Article XIV, Sec 7: For purposes of communication and instruction, the official languages of the Philippines are Filipino and, until otherwise provided by law, English. The regional languages are the official auxiliary languages in the regions and shall serve as auxiliary media of instruction therein. Spanish and Arabic shall be promoted on a voluntary and optional basis.

- ^ "Commission on the Filipino Language Act". Chan Robles Law Library. Retrieved July 19, 2007.

- ^ "Resolusyon Blg. 92–1" (in Filipino). Commission on the Filipino Language. May 13, 1992. Retrieved March 24, 2007.

- ^ "DepEd adds 7 mother-tongue languages in K to 12". July 12, 2013.

- ^ "K to 12 and beyond: A look back at Aquino's 10-point education agenda". June 24, 2016.

- ^ "Republic Act No. 11106" (PDF). Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. Retrieved September 10, 2023.

- ^ Takacs, Sarolta (2015). The Modern World: Civilizations of Africa, Civilizations of Europe, Civilizations of the Americas, Civilizations of the Middle East and Southwest Asia, Civilizations of Asia and the Pacific. Routledge. p. 659. ISBN 978-1-317-45572-1.

- ^ Brown, Michael Edward; Ganguly, Sumit (2003). Fighting Words: Language Policy and Ethnic Relations in Asia. MIT Press. pp. 323–325. ISBN 978-0-262-52333-2. Retrieved August 4, 2020.

- ^ Lopez, Cecilio (January 1, 1965). "The Spanish overlay in Tagalog". Lingua. 14: 477. doi:10.1016/0024-3841(65)90058-6. ISSN 0024-3841.

- ^ Baklanova, Ekaterina (March 20, 2017). "Types of Borrowings in Tagalog/Filipino". Kritika Kultura (28). doi:10.13185/KK2017.02803 (inactive November 1, 2024).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - ^ Donoso, Isaac J. (2010). "The Hispanic Moros y Cristianos and the Philippine Komedya". Philippine Humanities Review. 11: 87–120. ISSN 0031-7802.

Thus, Arabic words became integrated into Philippine languages through Spanish (e.g., alahas (alhaja, al- haja), alkalde (alcalde, al-qadi), alkampor (alcanfor, al-kafiir), alkansiya (alcancia, al-kanziyya), aldaba (aldaba, al-dabba), almires (almirez, al-mihras), baryo (barrio, al-barri), kapre (cafre, kafir), kisame (zaquizami, saqf fassami), etc.)

- ^ Haspelmath, Martin (2009). Loanwords in the World's Languages: A Comparative Handbook. De Gruyter Mouton. p. 724. ISBN 978-3-11-021843-5.

- ^ a b Rainier Alain, Ronda (March 22, 2013). "Bahasa in schools? DepEd eyes 2nd foreign language". The Philippine Star. Retrieved June 11, 2013.

- ^ Chan-Yap, Gloria (1980). Hokkien Chinese borrowings in Tagalog. Dept. of Linguistics, School of Pacific Studies, Australian National University. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-85883-225-1.

The number of loanwords in the domain of cookery is rather large, and they are, by far, the most homogeneous of the loanwords.

- ^ Joaquin, Nick (2004). Culture and history. Pasig. p. 42. ISBN 978-971-27-1426-9. OCLC 976189040.

- ^ Potet, Jean-Paul G. (2016). Tagalog Borrowings and Cognates. Raleigh, NC: Lulu Press, Inc. p. 343. ISBN 978-1-326-61579-6.

- ^ "Mexico, our older sister". Manila Bulletin News. Archived from the original on April 13, 2018. Retrieved April 13, 2018.

- ^ Ricardo Ma. Nolasco. "Maraming Wika, Matatag na Bansa – Chairman Nolasco" (in Filipino). Commission on the Filipino Language. Retrieved October 4, 2007.

- ^ Felongco, Gilbert (December 5, 2007). "Arroyo wants Spanish language in schools". GulfNews. Retrieved August 6, 2018.

- ^ Weedon, Alan (August 10, 2019). "The Philippines is fronting up to its Spanish heritage, and for some it's paying off". ABC News. Retrieved December 23, 2020.

- ^ Gonzales, Richard DLC. "Nihongo No Benkyou: Why and How Filipinos Learn Japanese Language". Academia.edu.

- ^ "Similarities and Differences between Japan and Philippine Cultures". www.slideshare.net. June 26, 2012.

- ^ Lewis, M. Paul; Simons, Gary F., eds. (2015). "Ethnologue: Languages of the World" (18 ed.). Dallas, Texas: SIL International.

- ^ a b c "Tagalog is the Most Widely Spoken Language at Home (2020 Census of Population and Housing)". Tagalog is the Most Widely Spoken Language at Home (2020 Census of Population and Housing). March 7, 2023.

- ^ Miller, Christopher (2010). "A Gujarati Origin for Scripts of Sumatra, Sulawesi and the Philippines" (PDF). Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society. 36 (1): 276. doi:10.3765/bls.v36i1.3917. ISSN 2377-1666.

- ^ "National Philippine Proverb in Various Philippine Languages". iloko.tripod.com.

- ^ "Household Population, Number of Households, and Average Household Size of the Philippines (2020 Census of Population and Housing)". Household Population, Number of Households, and Average Household Size of the Philippines (2020 Census of Population and Housing). March 23, 2022. Retrieved March 13, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Headland, Thomas N. (2003). "Thirty endangered languages in the Philippines". Work Papers of the Summer Institute of Linguistics, University of North Dakota Session. 47 (1). doi:10.31356/silwp.vol47.01.

- ^ "Mother Tongue-Based Learning Makes Lessons More Interactive and Easier for Students" (Press release). DepEd. October 24, 2016.

- ^ See, Stanley Baldwin (August 15, 2016). "A primer on Baybayin". GMA News Online. Retrieved August 6, 2018.

- ^ Muslim education program gets P252-M funding. Philippine Daily Inquirer. July 13, 2011.

- ^ Reyes, Carmela (August 22, 2007). "3 Bulacan courts to use Filipino in judicial proceedings". Inquirer.net. Archived from the original on October 12, 2007.

- ^ a b Adriano, Joel. "The Philippines: still grappling with English". Safe-democracy.org. Forum for a safer democracy. Retrieved February 15, 2015.

- ^ Abinales, P. N.; Amoroso, Donna J. (2005). State and Society in the Philippines. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-7425-1024-1.

- ^ Afable, Patricia (2008). "Compelling Memories and Telling Archival Documents and Photographs: The Search for the Baguio Japanese Community" (PDF). Asian Studies. 44 (1).

- ^ a b "Philippinealmanac.com". Archived from the original on July 1, 2012. Retrieved March 15, 2015.

- ^ Paul Kekai Manansala (September 5, 2006). "Quests of the Dragon and Bird Clan". Retrieved March 15, 2015.

- ^ "Ancient Japanese pottery in Boljoon town". May 30, 2011. Retrieved March 15, 2015.

- ^ "Philippines History, Culture, Civilization and Technology, Filipino". Retrieved March 15, 2015.

- ^ "Korean, foreign languages not Filipino subject replacement: DepEd". Philippine News Agency. Retrieved December 12, 2018.

- ^ "Indonesian Language Club – Embassy of Indonesia – Washington D.C." Archived from the original on April 30, 2016.

- ^ "Going Banana". Retrieved March 15, 2015.

- ^ "KINDING SINDAW". tabacofamily.com.

- ^ "The Indian in the Filipino". Inquirer.net. Archived from the original on June 21, 2015. Retrieved March 15, 2015.

- ^ Kesavapany, K.; Mani, A.; Ramasamy, P. (2008). Rising India and Indian Communities in East Asia. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. ISBN 9789812307996. Retrieved March 15, 2015.

- ^ Sandhu, K. S.; Mani, A. (2006). Indian Communities in Southeast Asia (First Reprint 2006). Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. ISBN 9789812304186. Retrieved March 15, 2015.

- ^ "Estadisticas: El idioma español en Filipinas". Retrieved March 15, 2015.

- ^ Gómez Armas, Sara. El español resiste en Filipinas, El País, 19 May 2021

- ^ "Spanish language in Philippines". Archived from the original on March 18, 2015. Retrieved March 1, 2015.

General references

- Bellwood, Peter; Fox, James; Tryon, Darrell (1995). The Austronesians: Historical and comparative perspectives. Department of Anthropology, Australian National University. ISBN 0-7315-2132-3.

- "Ethnologue report for Philippines".

- Lobel, Jason William; Tria, Wilmer Joseph S. (2000). An Satuyang Tataramon: A Study of the Bikol language. Lobel & Tria Partnership Co. ISBN 971-92226-0-3.

- Mintz, Malcolm Warren (2001). "Bikol". Facts About the World's Languages: An Encyclopedia of the World's Major Languages, Past and Present. ISBN 0-8242-0970-2.

- Reid, Lawrence A. (1971). Philippine minor Languages: Word lists and phonologies. University of Hawai'i Press. ISBN 0-87022-691-6.

- Rubino, Carl Ralph Galvez (1998). Tagalog-English English-Tagalog Dictionary. Hippocrene Books. ISBN 0-7818-0961-4.

- Rubino, Carl Ralph Galvez (2000). Ilocano Dictionary and Grammar. University of Hawai'i Press. ISBN 0-8248-2088-6.

- Rubino, Carl Ralph Galvez. "The Philippine National Proverb". Translated into various Philippine languages. Retrieved July 28, 2005.

- Sundita, Christopher Allen (2002). In Bahasa Sug: An Introduction to Tausug. Lobel & Tria Partnership. ISBN 971-92226-6-2.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Sundita, Christopher. "Languages or Dialects?". Understanding the Native Tongues of the Philippines. Archived from the original on June 16, 2006. Retrieved July 28, 2005.

- "The Constitution of the Republic of the Philippines". Government of the Philippines.

- Yap, Fe Aldave (1977). A Comparative Study of Philippine Lexicons. Institute of Philippine languages, Department of Education, Culture, and Sports. ISBN 971-8705-05-8.

- Zorc, R. David (1977). "The Bisayan dialects of the Philippines: Subgrouping and reconstruction". Pacific Linguistics. C (44).

- Zorc, R. David (2001). "Hiligaynon". Facts About the World's Languages: An Encyclopedia of the World's Major Languages, Past and Present.

- Viray, Joseph Reylan B. (2006). "Dagang Simbahan". Makata International Journal of Poetry. 7 (12).

- de la Rosa, Luciano (1960). "El Filipino: Origen y Connotación". El Renacimiento Filipino.

Further reading

- Dedaić, Mirjana N.; Nelson, Daniel N. (2003). At War With Words. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-017649-1. Retrieved October 4, 2007.

- Hamers, Josiane F. (2000). Bilinguality and Bilingualism. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-64843-2. Retrieved October 4, 2007.

- Tupas, Ruanni (2015). "The Politics of "P" and "F": A Linguistic History of Nation-Building in the Philippines". Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development. 36 (6): 587–597. doi:10.1080/01434632.2014.979831. S2CID 143332545.

- Thompson, Roger M. (January 1, 2003). Filipino English and Taglish: Language Switching from Multiple Perspectives. John Benjamins Publishing. ISBN 9789027248916.

External links

- Linguistic map of the Philippines at Muturzikin.com

- Ricardo Maria Nolasco on the diversity of languages in the Philippines

- Lawrence R. Reid webpage of Dr. Lawrence A. Reid. Researcher Emeritus of linguistics at the University of Hawai'i at Manoa. Has researched Philippine languages for decades.

- The Metamorphosis of Filipino as a National Language

- Carl Rubino webpage of Dr. Carl Rubino. A Filipino linguist who has studied Philippine languages.

- Literatura hispanofilipina: siglos XVII al XX by Edmundo Farolan Romero, with a brief Philippine poetry anthology in Spanish.

- Salita Blog by Christopher Sundita. A blog about a variety of issues concerning the languages of the Philippines.

- Espaniero An Online Spanish conversation group for Pinoys

- Philippine Language Tree

- The Language Planning Situation in the Philippines, by Andrew González, FSC

- kaibigankastila webpage of the Spanish culture in the Philippines.

- On linguistic mutual intolerance in the Philippines

- Filipino Translator

- Tagalog Translator Online Online dictionary for translating Tagalog from/to English, including expressions and latest headlines regarding the Philippines.

- Linguistic map of the Philippines

- Learn Philippine Languages a compilation of lessons about languages of the Philippines.

![]() Media related to Languages of the Philippines at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Languages of the Philippines at Wikimedia Commons